April 2020

By Michael T. Klare

The U.S. Department of Defense’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2021 includes $28.9 billion for modernizing the U.S. nuclear weapons complex, twice the amount requested for the current fiscal year and a major signal of the Trump administration’s strategic priorities. Included in this request are billions of dollars for the procurement of new nuclear delivery systems, including the B-21 bomber, the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, and an advanced intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

However, the largest program request in the modernization budget, totaling $7 billion, is not for any of those weapons but for modernizing the nation’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) infrastructure, the electronic systems that inform national leaders of a possible enemy attack and enable the president to order the launch of U.S. bombers and missiles. The administration avows it will use this amount to replace outdated equipment with more modern and reliable systems and to protect against increasingly severe cyberattacks. Equally pressing, for Pentagon planners, is a drive to increase the automation of these systems, a goal that has certain attractions in terms of increased speed and accuracy, but also one that raises troubling questions about the role of machines in deciding humanity’s fate in a future nuclear showdown.

However, the largest program request in the modernization budget, totaling $7 billion, is not for any of those weapons but for modernizing the nation’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) infrastructure, the electronic systems that inform national leaders of a possible enemy attack and enable the president to order the launch of U.S. bombers and missiles. The administration avows it will use this amount to replace outdated equipment with more modern and reliable systems and to protect against increasingly severe cyberattacks. Equally pressing, for Pentagon planners, is a drive to increase the automation of these systems, a goal that has certain attractions in terms of increased speed and accuracy, but also one that raises troubling questions about the role of machines in deciding humanity’s fate in a future nuclear showdown.

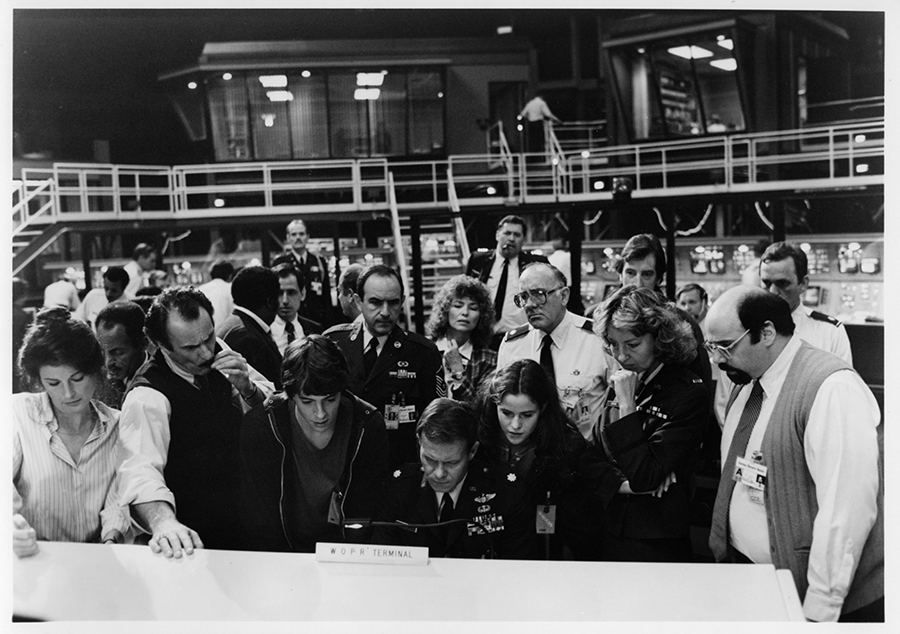

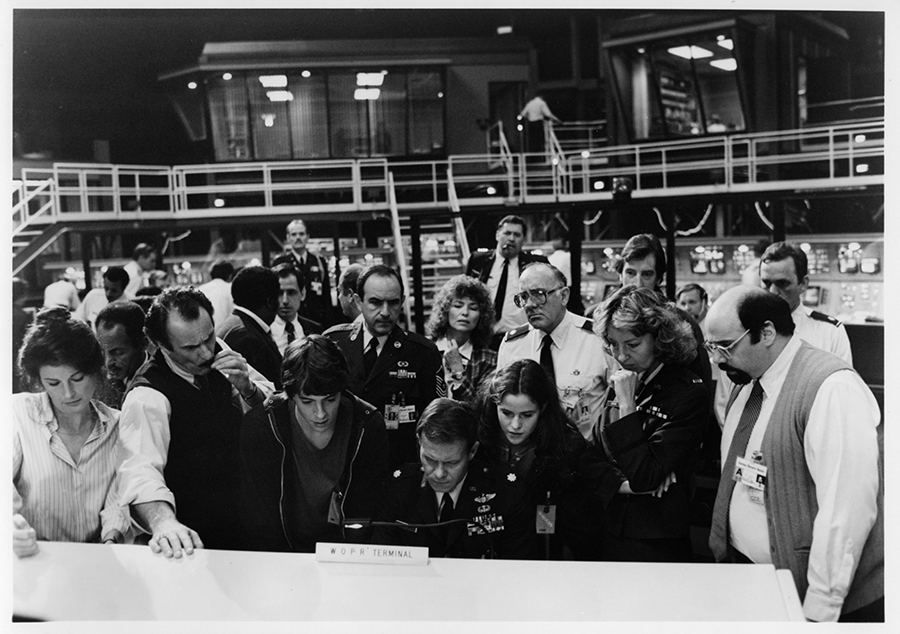

Science fiction filmmakers have long envisioned the possibility of machines acquiring the capacity to launch nuclear weapons on their own. The 1964 movie “Dr. Strangelove” presupposes that the Soviet Union has installed a “doomsday machine” primed to detonate automatically should the country come under attack by U.S. nuclear forces. When the U.S. leadership fails to halt such an attack by a rogue Air Force general, the doomsday scenario is set in motion. In 1983’s “WarGames,” a teenage hacker inadvertently ignites a nuclear crisis when he hacks into the (fictional) War Operation Plan Response (WOPR) supercomputer and the machine, believing it is simply playing a game, attempts to fight World War III on its own. Yet another vision of computers run amok was portrayed a year later in “The Terminator,” in which a superintelligent computer known as Skynet again controls U.S. nuclear weapons and elects to eliminate all humans by igniting a catastrophic nuclear war.

To be sure, none of the plans for NC3 automation now being considered by the Defense Department resemble anything quite like the WOPR or Skynet. Yet, these plans do involve developing essential building blocks for a highly automated command and control system that will progressively diminish the role of humans in making critical decisions over the use of nuclear weapons. Humans may be accorded the final authority to launch nuclear bombers and missiles, but assessments of enemy moves and intentions and the winnowing down of possible U.S. responses will largely be conducted by machines relying on artificial intelligence (AI).

The NC3 Modernization Drive

The total overhaul of the U.S. NC3 infrastructure was first proposed in the administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) report of February 2018. The existing system, the report stated, “is a legacy of the Cold War, last comprehensively updated almost three decades ago.” Although many of its individual components—early-warning satellites and radars, communications satellites and ground stations, missile launch facilities, national command centers—had been modernized over time, much of the interconnecting hardware and software has become obsolete, the Pentagon stated. The growing effectiveness of cyberattacks, moreover, was said to pose an ever-increasing threat to the safety and reliability of critical systems. To ensure that the president enjoyed timely warning of enemy attacks and was able to order appropriate responses, even under conditions of intense nuclear assault and cyberattack, the entire system would have to be rebuilt.

Given these highly demanding requirements, the NPR report called for overhauling the existing NC3 system and replacing many of its component parts with more modern, capable upgrades. Key objectives, it stated, include strengthening protection against cyber and space-based threats, enhancing integrated tactical warning and attack assessment, and advancing decision-support technology. These undertakings are ambitious and costly and go a long way toward explaining that $7 billion budget request for fiscal year 2021. Equally large sums are expected to be requested in the years ahead. In January 2019, the Congressional Budget Office projected that the cost of modernizing the U.S. NC3 system over the next 10 years will total $77 billion.1

The NPR report, as well as the budget documents submitted in 2020 in accordance with its dictates, do not identify increased automation as a specific objective of this overhaul. That is so, in part, because automation is already built into many of the systems incorporated into the existing NC3 system, such as launch-detection radars, and will remain integral to their replacements. At the same time, many proposed systems, such as decision-support technology—algorithms designed to assess enemy intentions and devise possible countermoves from which combat commanders can choose—are still in their infancy. Nevertheless, virtually every aspect of the NC3 upgrade is expected to benefit from advances in AI and machine learning.

The Allure of Automation

The quest to further automate key elements of the U.S. NC3 architecture is being driven largely by an altered perception of the global threat environment. Although the existing framework was always intended to provide decisionmakers with prompt warning of enemy nuclear attack and to operate even under conditions of nuclear war, the operational challenges faced by that system have grown more severe in recent years. Most notably, the decision-making system is threatened by the ever-increasing destructive capacity of conventional weapons, the growing sophistication of cyberattacks, and, as a result of those two, the growing speed of combat.

The existing NC3 architecture was designed in the previous century to detect enemy ICBM and bomber launches and provide decision-makers with enough time, as much as 30 minutes in the case of ICBM attacks, to assess the accuracy of launch warnings and still ponder appropriate responses. These systems did not always work as intended—the history of the Cold War is replete with false warnings of enemy attacks—but the cushion of time prevented a major catastrophe.2 The reasonably clear distinction between conventional and nuclear weapons, moreover, enabled military analysts to avoid confusing non-nuclear assaults with possibly nuclear ones.

With the introduction of increasingly capable conventional weapons, however, the distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear weapons is being blurred. Many of the new conventionally armed (but possibly nuclear-capable) ballistic missiles now being developed by the major powers are capable of hypersonic speed (more than five times the speed of sound) and of flying more than 500 kilometers (the limit imposed by the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty) and are intended for attacks on high-value enemy targets, such as air defense radars and command-and-control facilities. With flight durations of as little as five minutes, defensive NC3 systems have precious little time to determine whether incoming missiles are armed with nuclear or conventional missiles and to select an appropriate response, possibly including the early use of nuclear weapons.3

Cybercombat occurs at an even faster speed, potentially depriving nuclear commanders of critical information and communication links in a time of crisis and thereby precipitating inadvertent escalation.4 In the highly contested environment envisioned by the 2018 NPR report, decision-makers may be faced with an overload of inconclusive information and have mere minutes in which to grasp the essential reality and decide on humanity’s fate.

Under these circumstances, some analysts argue, increased NC3 automation will prove essential. They claim that increased reliance on AI can help with two of the existing system’s most acute challenges: information overload and time compression. With ever more sensors, (satellite monitors, ground radars, and surveillance aircraft) feeding intelligence into battle management systems, commanders are being inundated with information on enemy actions, preventing prompt and considered decision-making. At the same time, the use of more hypersonic missiles and advanced cyberweaponry has compressed the time in which such decisions must be made. AI could help overcome these challenges by sifting through the incoming data at lightning speed and highlighting the most important results and by distinguishing false warnings of nuclear attack from genuine ones.5

Automation could be even more useful, advocates claim, in helping commanders, up to and including the president, decide on nuclear and non-nuclear responses to confirmed indications of an enemy attack. With little time to act, human decision-makers could receive a menu of possible options devised by algorithms. “As the complexity of AI systems matures,” the Congressional Research Service noted in 2019, “AI algorithms may also be capable of providing commanders with a menu of viable courses of action based on real-time analysis of the battle-space, in turn enabling faster adaptation to complex events.”6

Some analysts have gone even further, suggesting that in conditions of extreme time compression, the machines could be empowered to select the optimal response and initiate the attack themselves. “Attack-time compression has placed America’s senior leadership in a situation where the existing NC3 system may not act rapidly enough,” Adam Lowther and Curtis McGiffin wrote in a commentary at War on the Rocks, a security-oriented website. “Thus, it may be necessary to develop a system based on [AI], with predetermined response decisions, that detects, decides, and directs strategic forces with such speed that the attack-time compression challenge does not place the United States in an impossible position.”7

That commentary provoked widespread alarm about the possible loss of human control over decisions of  nuclear use. Even some military officials expressed concern over such notions. “You will find no stronger proponent of integration of AI capabilities writ large into the Department of Defense,” said Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan, director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), at a September 2019 conference at Georgetown University, “but there is one area where I pause, and it has to do with nuclear command and control.” Referring to the article’s assertion that an automated U.S. nuclear launch ability is needed, he said, “I read that. And my immediate answer is, ‘No. We do not.’”8

nuclear use. Even some military officials expressed concern over such notions. “You will find no stronger proponent of integration of AI capabilities writ large into the Department of Defense,” said Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan, director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), at a September 2019 conference at Georgetown University, “but there is one area where I pause, and it has to do with nuclear command and control.” Referring to the article’s assertion that an automated U.S. nuclear launch ability is needed, he said, “I read that. And my immediate answer is, ‘No. We do not.’”8

Shanahan indicated that his organization was moving to integrate AI technologies into a wide array of non-nuclear capabilities, including command-and-control functions. Indeed, JAIC and other military components are moving swiftly to develop automated command-and-control systems and to ready them for use by regular combat forces. Initially, these systems will be employed by conventional forces, but the Pentagon fully intends to merge them over time with their nuclear counterparts.

Multidomain Command and Control

The Pentagon’s principle mechanism for undertaking this vast enterprise is called the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) project. Being overseen by the Air Force, it is a computer-driven system for collecting sensor data from myriad platforms, organizing that data into manageable accounts of enemy positions, and delivering those summaries at machine speed to all combat units engaged in an operation. “First and foremost, you gotta connect the joint team,” General David L. Goldfein, Air Force chief of staff, said in January. “We have to have access to common data so that we can operate at speed and bring all domain capabilities against an adversary.”9

The JADC2 enterprise is said to be a core element of the Pentagon’s emerging strategy for U.S. victory in the fast-paced wars of the future. Called All-Domain Operations, the new strategy assumes seamless coordination among all elements of the U.S. military. General John E. Hyten, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained that the strategy combines “space, cyber, deterrent [conventional and nuclear forces], transportation, electromagnetic spectrum operations, missile defense—all of these global capabilities together … to compete with a global competitor and at all levels of conflict.”10

In moving forward on this, the Pentagon’s initial emphasis is likely to be on “data fusion,” or the compression of multiple sensor inputs into concise summaries that can be rapidly communicated to and understood by commanders in the field. Over time, however, the JADC2 project is expected to incorporate AI-enabled decision-support systems, or algorithms intended to narrow down possible responses to enemy moves and advise those commanders on the optimal choice.

This all matters because the Defense Department has indicated that the JADC2 system, while primarily intended for use by non-nuclear forces, will eventually be integrated with the nuclear command and control system now being overhauled. In his interview, Hyten was asked if the emerging JADC2 architecture was going to inform development of the remodeled NC3. He responded, “Yes. The answer is yes. But it’s important to realize that JADC2 and NC3 are intertwined.” Hyten, who formerly served as commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, added that some NC3 elements will have to be separated from the JADC2 system “because of the unique nature of the nuclear business.” Nevertheless, “NC3 will operate in significant elements of JADC2,” and, as a result, “NC3 has to inform JADC2 and JADC2 has to inform NC3.”11

Stripped of jargon and acronyms, Hyten is saying that the automated systems now being assembled for the U.S. multidomain command-and-control enterprise will provide a model for the nation’s nuclear command-and-control system, or be incorporated into the system, or both. In a future crisis, moreover, data on conventional operations being overseen by the JADC2 system will automatically be fed into NC3 computerized intelligence-gathering systems, possibly altering their assessment of the nuclear threat and leading to a heightened level of alert and possibly a greater risk of inadvertent or precipitous nuclear weapons use.

Parallel Developments Elsewhere

While the United States is proceeding with plans to modernize and automate its nuclear command-and-control system, other nuclear-armed nations, especially China and Russia, are also moving in this direction. It is conceivable, then, that a time could come when machines on all sides will dictate the dynamics of a future nuclear crisis and possibly determine the onset and prosecution of a nuclear war.

Russia’s pursuit of NC3 automation began during the Soviet era, when senior leaders, fearing a “decapitating” attack on the Soviet leadership as part of a preemptive U.S. first strike, ordered the development of a “dead hand” system intended to launch Soviet missiles even in the absence of instructions to do so from Moscow. If the system, known as Perimeter, detected a nuclear explosion and received no signals from Moscow (indicating a nuclear detonation there), it was programmed to inform nuclear launch officers who, in turn, were authorized to initiate retaliatory strikes without further instruction.12 According to Russian media accounts, the Perimeter system still exists and employs some form of AI.13

Russia’s pursuit of NC3 automation began during the Soviet era, when senior leaders, fearing a “decapitating” attack on the Soviet leadership as part of a preemptive U.S. first strike, ordered the development of a “dead hand” system intended to launch Soviet missiles even in the absence of instructions to do so from Moscow. If the system, known as Perimeter, detected a nuclear explosion and received no signals from Moscow (indicating a nuclear detonation there), it was programmed to inform nuclear launch officers who, in turn, were authorized to initiate retaliatory strikes without further instruction.12 According to Russian media accounts, the Perimeter system still exists and employs some form of AI.13

Today, Russia’s leadership appears to be pursuing a strategy similar to that being pursued in the United States, involving increased reliance on AI and automation in nuclear and conventional command and control. In 2014, Russia inaugurated the National Defense Control Center (NDCC) in Moscow, a centralized command post for assessing global threats and initiating whatever military action is deemed necessary, whether nuclear or non-nuclear. Like the U.S. JADC2 system, the NDCC is designed to collect information on enemy moves from multiple sources and provide senior officers with guidance on possible responses.14

China is also investing in AI-enabled data fusion and decision-support systems, although less is known about its efforts in this area. One comprehensive study of Chinese thinking on the application of AI to warfare reported that Chinese strategists believe that AI and other emerging technologies will transform the nature of future combat, and so, to achieve victory, the People’s Liberation Army must seek superiority in this realm.15

The Perils of Heedless Automation

There are many reasons to be wary of increasing the automation of nuclear command and control, especially when it comes to computer-assisted decision-making. Many of these technologies are still in their infancy and prone to malfunctions that cannot easily be anticipated. Algorithms that have developed through machine learning, a technique whereby computers are fed vast amounts of raw data and are “trained” to detect certain patterns, can become very good at certain tasks, such as facial recognition, but often contain built-in biases conveyed through the training data. These systems also are prone to unexplainable malfunctions and can be fooled, or “spoofed,” by skilled professionals. No matter how much is spent on cybersecurity, moreover, NC3 systems will always be vulnerable to hacking by sophisticated adversaries.16

AI-enabled systems also lack an ability to assess intent or context. For example, does a sudden enemy troop redeployment indicate an imminent enemy attack or just the normal rotation of forces? Human analysts can use their sense of the current political moment to help shape their assessment of such a situation, but machines lack that ability and may tend to assume the worst.

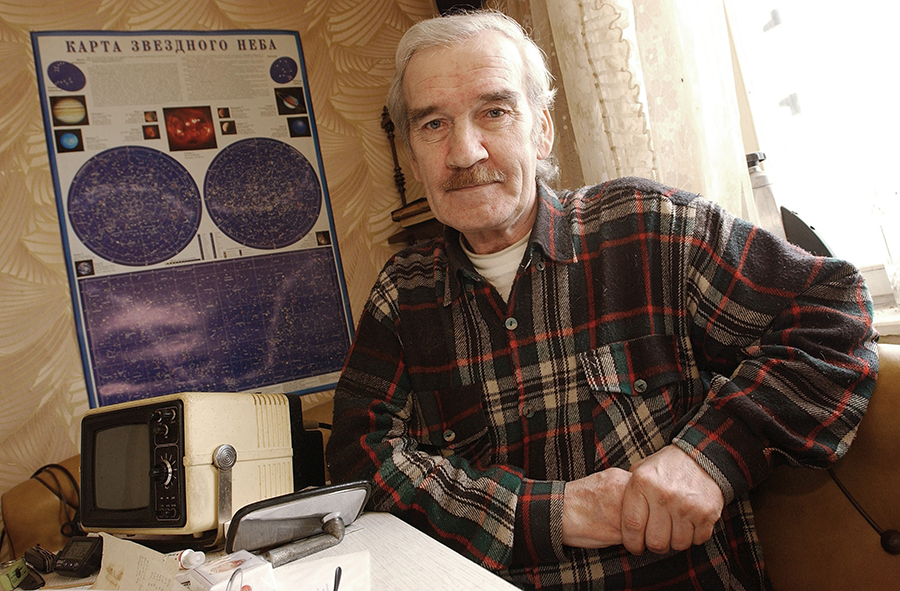

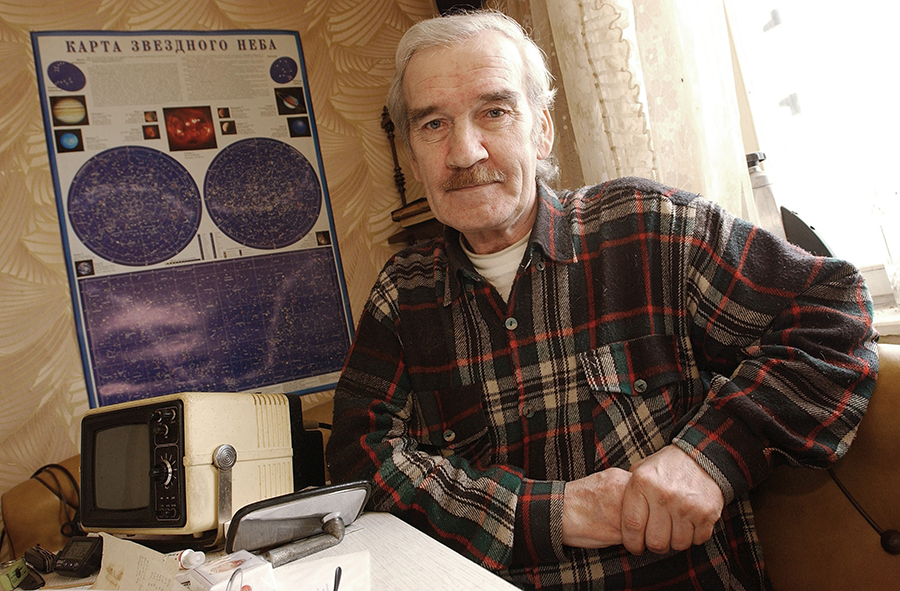

This aspect of human judgment arose in a famous Cold War incident. In September 1983, at a time of heightened tensions between the superpowers, a Soviet nuclear watch officer, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, received an electronic warning of a U.S. missile attack on Soviet territory. Unsure of the accuracy of the warning, he waited before informing his superiors of the strike and eventually told them he believed it was a computer error, as proved to be the case, thus averting a possible nuclear exchange. Machines are not capable of such doubts or hesitations.17

Another problem is the lack of real world data for use in training NC3 algorithms. Other than the two bombs dropped on Japan at the end of World War II, there has never been an actual nuclear war and therefore no genuine combat examples for use in devising reality-based attack responses. War games and simulations can be substituted for this purpose, but none of these can accurately predict how leaders will actually behave in a future nuclear showdown. Therefore, decision-support programs devised by these algorithms can never be fully trusted. “Automated decision-support systems … are only as good as the data they rely on. Building an automated decision-support tool to provide early warning of a preemptive nuclear attack is an inherently challenging problem because there is zero actual data of what would constitute reliable indicators of an imminent preemptive nuclear attack.”18

An equal danger is what analysts call “automation bias,” or the tendency for stressed-out decision-makers to trust the information and advice supplied by advanced computers rather than their own considered judgment. For example, a U.S. president, when informed of sensor data indicating an enemy nuclear attack and under pressure to make an immediate decision, might choose to accept the computer’s advice to initiate a retaliatory strike rather than consider possible alternatives, such as with Petrov’s courageous Cold War action. Given that AI data systems can be expected to gain ever more analytical capacity over the coming decades, “it is likely that humans making command decisions will treat the AI system’s suggestions as on a par with or better than those of human advisers,” a 2018 RAND study noted. “This potentially unjustified trust presents new risks that must be considered.”19

Compounding all these risks is the likelihood that China, Russia, and the United States will all install automated NC3 systems but without informing each other of the nature and status of these systems. Under these circumstances, it is possible to imagine a “flash war,” roughly akin to a “flash crash” on Wall Street, that is triggered by the interaction of competing corporate investment algorithms. In such a scenario, the data assessment systems of each country could misinterpret signs of adversary moves and conclude an attack is imminent, leading other computers to order preparatory moves for a retaliatory strike, in turn prompting the similar moves on the other side, until both commence a rapid escalatory cycle ending in nuclear catastrophe.20

Given these multiple risks, U.S. policymakers and their Chinese and Russian counterparts should be very leery of accelerating NC3 automation. Indeed, Shanahan acknowledged as much, saying nuclear command and control “is the ultimate human decision that needs to be made…. We have to be very careful,” especially given “the immaturity of technology today.”

Exercising prudence in applying AI to nuclear command and control is the responsibility, first and foremost, of national leaders of the countries involved. In the United States, military officials have pledged to expose all new AI applications to rigorous testing, but Congress needs to play a more active role in overseeing these endeavors and questioning the merits of proposed innovations. At the same time, all three nuclear powers would benefit from mutual consultations over the perils inherent in increased NC3 automation and what technical steps might be taken to reduce the risk of inadvertent or accidental war. This could occur as an independent venture or in the context of the irregular strategic stability talks held by senior U.S. and Russian representatives.

There is no more fateful decision a leader can make than to order the use of nuclear weapons. Ideally, such a decision will never have to be made. But so long as nuclear weapons exist, humans, not machines, must exercise ultimate control over their use.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. Congressional Budget Office, “Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2019 to 2028,” January 2019, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-01/54914-NuclearForces.pdf.

2. For an account of nuclear control accidents during the Cold War, see Scott D. Sagan, The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

3. Michael T. Klare, “An ‘Arms Race in Speed’: Hypersonic Weapons and the Changing Calculus of Battle,” Arms Control Today, June 2019.

4. Michael T. Klare, “Cyber Battles, Nuclear Outcomes? Dangerous New Pathways to Escalation,” Arms Control Today, November 2019.

5. Kelley M. Sayler, “Artificial Intelligence and National Security,” CRS Report, R45178, November 21, 2019, pp. 12–13, 28–29.

6. Ibid., p. 13.

7. Adam Lowther and Curtis McGiffin, “America Needs a ‘Dead Hand,’” War on the Rocks, August 16, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/08/america-needs-a-dead-hand/.

8. Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “No AI for Nuclear Command and Control: JAIC’s Shanahan,” Breaking Defense, September 25, 2019, https://breakingdefense.com/2019/09/no-ai-for-nuclear-command-control-jaics-shanahan/.

9. Theresa Hitchens, “New Joint Warfighting Plan Will Help Define ‘Top Priority’ JADC2: Hyten,” Breaking Defense, January 29, 2020, https://breakingdefense.com/2020/01/new-joint-warfighting-plan-will-help-define-top-priority-jadc2-hyten/.

10. Ibid.

11. Colin Clark, “Nuclear C3 Goes All Domain: Gen. Hyten,” Breaking Defense, February 20, 2010, https://breakingdefense.com/2020/02/nuclear-c3-goes-all-domain-gen-hyten/.

12. Michael C. Horowitz, Paul Scharre, and Alexander Velez-Green, “A Stable Nuclear Future? The Impact of Autonomous Systems and Artificial Intelligence,” December 2019, pp. 12–13, https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1912/1912.05291.pdf.

13. See, for example, Edward Geist and Andrew J. Lohn, “How Might Artificial Intelligence Affect the Risk of Nuclear War?” RAND Corp., 2018, p. 10, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE296/RAND_PE296.pdf.

14. See Tyler Rogoway, “Look Inside Putin’s Massive New Military Command and Control Center,” Jalopnik, November 19, 2015, https://foxtrotalpha.jalopnik.com/look-inside-putins-massive-new-military-command-and-con-1743399678.

15. Elsa B. Kania, “Battlefield Singularity: Artificial Intelligence, Military Revolution, and China’s Future Military Power,” Center for a New American Security, November 2017, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/Battlefield-Singularity-November-2017.pdf?mtime=20171129235805.

16. See Sayler, “Artificial Intelligence and National Security,” pp. 29–33.

17. On the Petrov incident, see Paul Scharre, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), pp. 1–2.

18. Horowitz, Scharre, and Velez-Green, “Stable Nuclear Future?” p. 17.

19. Geist and Lohn, “How Might Artificial Intelligence Affect the Risk of Nuclear War?” p. 18.

20. Scharre, Army of None, pp. 199–230.

Michael T. Klare is a professor emeritus of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association. This article is the fourth in the “Arms Control Tomorrow” series, in which he considers disruptive emerging technologies and their implications for war-fighting and arms control.

Twenty years ago, John Steinbruner, then the chair of the Arms Control Association Board of Directors, warned in his book Principles of Global Security that globalization is generating “a new class of security problems in which dispersed processes pose dangers of large magnitude and incalculable probability.” He argued that policymakers “will have to shift from contingency reaction to anticipatory prevention” and “this will have to be done in global coalition.”

Twenty years ago, John Steinbruner, then the chair of the Arms Control Association Board of Directors, warned in his book Principles of Global Security that globalization is generating “a new class of security problems in which dispersed processes pose dangers of large magnitude and incalculable probability.” He argued that policymakers “will have to shift from contingency reaction to anticipatory prevention” and “this will have to be done in global coalition.”

Antonov was appointed ambassador to the United States in August 2017. For more than three decades, he has served in the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its successor, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he has specialized in the control of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. Serving as the ministry’s director for security and disarmament, he headed Russia’s delegation to the 2009 negotiations on the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). He was appointed deputy minister of defense in 2011 and deputy minister of foreign affairs in 2016.

Antonov was appointed ambassador to the United States in August 2017. For more than three decades, he has served in the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its successor, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he has specialized in the control of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. Serving as the ministry’s director for security and disarmament, he headed Russia’s delegation to the 2009 negotiations on the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). He was appointed deputy minister of defense in 2011 and deputy minister of foreign affairs in 2016. However, we have yet to get a response. Trump administration representatives keep claiming that “there is still time” since the extension of the treaty in their view can be formalized in a matter of days. These statements are made despite our repeated clarifications that New START’s extension is not a “mere technicality,” but a rather extensive process that requires the Russian side to undertake a series of domestic legislative procedures. I would like to reiterate that as past similar review processes show, it may take several months to complete the New START extension.

However, we have yet to get a response. Trump administration representatives keep claiming that “there is still time” since the extension of the treaty in their view can be formalized in a matter of days. These statements are made despite our repeated clarifications that New START’s extension is not a “mere technicality,” but a rather extensive process that requires the Russian side to undertake a series of domestic legislative procedures. I would like to reiterate that as past similar review processes show, it may take several months to complete the New START extension. However, the largest program request in the modernization budget, totaling $7 billion, is not for any of those weapons but for modernizing the nation’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) infrastructure, the electronic systems that inform national leaders of a possible enemy attack and enable the president to order the launch of U.S. bombers and missiles. The administration avows it will use this amount to replace outdated equipment with more modern and reliable systems and to protect against increasingly severe cyberattacks. Equally pressing, for Pentagon planners, is a drive to increase the automation of these systems, a goal that has certain attractions in terms of increased speed and accuracy, but also one that raises troubling questions about the role of machines in deciding humanity’s fate in a future nuclear showdown.

However, the largest program request in the modernization budget, totaling $7 billion, is not for any of those weapons but for modernizing the nation’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) infrastructure, the electronic systems that inform national leaders of a possible enemy attack and enable the president to order the launch of U.S. bombers and missiles. The administration avows it will use this amount to replace outdated equipment with more modern and reliable systems and to protect against increasingly severe cyberattacks. Equally pressing, for Pentagon planners, is a drive to increase the automation of these systems, a goal that has certain attractions in terms of increased speed and accuracy, but also one that raises troubling questions about the role of machines in deciding humanity’s fate in a future nuclear showdown. nuclear use. Even some military officials expressed concern over such notions. “You will find no stronger proponent of integration of AI capabilities writ large into the Department of Defense,” said Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan, director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), at a September 2019 conference at Georgetown University, “but there is one area where I pause, and it has to do with nuclear command and control.” Referring to the article’s assertion that an automated U.S. nuclear launch ability is needed, he said, “I read that. And my immediate answer is, ‘No. We do not.’”

nuclear use. Even some military officials expressed concern over such notions. “You will find no stronger proponent of integration of AI capabilities writ large into the Department of Defense,” said Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan, director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), at a September 2019 conference at Georgetown University, “but there is one area where I pause, and it has to do with nuclear command and control.” Referring to the article’s assertion that an automated U.S. nuclear launch ability is needed, he said, “I read that. And my immediate answer is, ‘No. We do not.’” Russia’s pursuit of NC3 automation began during the Soviet era, when senior leaders, fearing a “decapitating” attack on the Soviet leadership as part of a preemptive U.S. first strike, ordered the development of a “dead hand” system intended to launch Soviet missiles even in the absence of instructions to do so from Moscow. If the system, known as Perimeter, detected a nuclear explosion and received no signals from Moscow (indicating a nuclear detonation there), it was programmed to inform nuclear launch officers who, in turn, were authorized to initiate retaliatory strikes without further instruction.

Russia’s pursuit of NC3 automation began during the Soviet era, when senior leaders, fearing a “decapitating” attack on the Soviet leadership as part of a preemptive U.S. first strike, ordered the development of a “dead hand” system intended to launch Soviet missiles even in the absence of instructions to do so from Moscow. If the system, known as Perimeter, detected a nuclear explosion and received no signals from Moscow (indicating a nuclear detonation there), it was programmed to inform nuclear launch officers who, in turn, were authorized to initiate retaliatory strikes without further instruction. UK authorities determined that the chemical in the perfume bottle belonged to a class of nerve agents known as Novichoks, one of which had just been used in the attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal, a former Russian agent who defected to the UK, in the nearby town of Salisbury in March 2018. That attack also poisoned Skripal’s daughter and two police officers. The UK has accused Russia of being behind the plot and has charged two Russian intelligence officers with conducting the attack. In response, the UK and its allies expelled more than 100 Russian diplomats suspected of being spies and imposed sanctions on Russia and government officials who were involved in the assassination plot.

UK authorities determined that the chemical in the perfume bottle belonged to a class of nerve agents known as Novichoks, one of which had just been used in the attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal, a former Russian agent who defected to the UK, in the nearby town of Salisbury in March 2018. That attack also poisoned Skripal’s daughter and two police officers. The UK has accused Russia of being behind the plot and has charged two Russian intelligence officers with conducting the attack. In response, the UK and its allies expelled more than 100 Russian diplomats suspected of being spies and imposed sanctions on Russia and government officials who were involved in the assassination plot. Before that Conference of the States Parties was set to meet in The Hague on November 25–29, 2019, both sides engaged in quiet diplomacy behind the scenes. On April 30, 2019, Russia proposed quadripartite consultations with the sponsors of the joint proposal to merge the two proposals into a “compromise” document. The joint sponsors refused this offer and insisted that the conference vote on the proposals separately. In light of this stance and the Technical Secretariat’s determination that the chemicals included in the fifth element of the Russian proposal did not meet the criteria for inclusion in Schedule 1, Russia recognized that its effort to include the fifth element of its proposal would not gain support among other states-parties. In September, Russia modified its proposal to drop the fifth element. This move enabled the conference to approve both proposals by consensus.

Before that Conference of the States Parties was set to meet in The Hague on November 25–29, 2019, both sides engaged in quiet diplomacy behind the scenes. On April 30, 2019, Russia proposed quadripartite consultations with the sponsors of the joint proposal to merge the two proposals into a “compromise” document. The joint sponsors refused this offer and insisted that the conference vote on the proposals separately. In light of this stance and the Technical Secretariat’s determination that the chemicals included in the fifth element of the Russian proposal did not meet the criteria for inclusion in Schedule 1, Russia recognized that its effort to include the fifth element of its proposal would not gain support among other states-parties. In September, Russia modified its proposal to drop the fifth element. This move enabled the conference to approve both proposals by consensus. The nuclear security enterprise is embarking on its most ambitious level of effort since the Cold War era. The NNSA is currently managing four weapons modernization programs, proposing a fifth, and undertaking infrastructure projects that affect every strategic material and component used in nuclear weapons.

The nuclear security enterprise is embarking on its most ambitious level of effort since the Cold War era. The NNSA is currently managing four weapons modernization programs, proposing a fifth, and undertaking infrastructure projects that affect every strategic material and component used in nuclear weapons. In a March 26 interview with Arms Control Today, conference president-designate Gustavo Zlauvinen of Argentina said that after extensive consultations, he circulated a proposal on March 25 to NPT regional groups to postpone the review conference “until such time as conditions permit, but not later than April 2021.”

In a March 26 interview with Arms Control Today, conference president-designate Gustavo Zlauvinen of Argentina said that after extensive consultations, he circulated a proposal on March 25 to NPT regional groups to postpone the review conference “until such time as conditions permit, but not later than April 2021.”

Under the 2015 nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran’s LEU stockpile is capped at 300 kilograms of uranium hexafluoride gas enriched to 3.67 percent uranium-235 and is limited to output from 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz. Three hundred kilograms of uranium hexafluoride gas equates to about 202 kilograms of uranium by weight.

Under the 2015 nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran’s LEU stockpile is capped at 300 kilograms of uranium hexafluoride gas enriched to 3.67 percent uranium-235 and is limited to output from 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz. Three hundred kilograms of uranium hexafluoride gas equates to about 202 kilograms of uranium by weight. IAEA Director-General Rafael Grossi laid out the agency’s attempts since January 2019 to get information from Tehran about the possible storage and use of nuclear materials at three locations in Iran in a March 3 report to the agency’s Board of Governors.

IAEA Director-General Rafael Grossi laid out the agency’s attempts since January 2019 to get information from Tehran about the possible storage and use of nuclear materials at three locations in Iran in a March 3 report to the agency’s Board of Governors. At the same time, the Trump administration continued to deflect questions about its stance on the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is due to expire in 2021.

At the same time, the Trump administration continued to deflect questions about its stance on the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is due to expire in 2021. “Until we make a final decision on the path forward, I am not prepared to recapitalize aircraft,” Esper told the Senate Armed Services Committee during a March 4 hearing. “We still have the means to conduct the overflights,” he added, “[b]ut at this time, we’re holding until we get better direction.”

“Until we make a final decision on the path forward, I am not prepared to recapitalize aircraft,” Esper told the Senate Armed Services Committee during a March 4 hearing. “We still have the means to conduct the overflights,” he added, “[b]ut at this time, we’re holding until we get better direction.”