December 2020

By Tobias Vestner

The 2013 Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) sets international standards for the transfer of conventional weapons. The United States was heavily involved in the treaty’s negotiation, but has moved to the sidelines during the Trump administration, whereas China now engages more actively. In light of shifting balances of power and rising great power competition, these developments have several effects on the ATT and international cooperation regarding global arms transfers, eventually indicating a new phase of multilateralism in international security.

Originally, the United States, the world’s largest arms exporter, supported and significantly shaped the treaty negotiations. Washington aimed to encourage other nations to better regulate international arms transfers in line with U.S. standards. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry signed the treaty in September 2013, but domestic politics prevented the Obama administration from ratifying the agreement. Nonetheless, the U.S. signature signaled its commitment to other states and enabled Washington to engage in many of the treaty’s activities.

Originally, the United States, the world’s largest arms exporter, supported and significantly shaped the treaty negotiations. Washington aimed to encourage other nations to better regulate international arms transfers in line with U.S. standards. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry signed the treaty in September 2013, but domestic politics prevented the Obama administration from ratifying the agreement. Nonetheless, the U.S. signature signaled its commitment to other states and enabled Washington to engage in many of the treaty’s activities.

The next administration, however, followed a different course. President Donald Trump announced in April 2019 that the United States no longer supported the treaty and that the administration would not seek to ratify the treaty.1 Even if the Biden administration were to reverse this decision, the United States appears disinterested or at the very least ambivalent about the ATT.

Meanwhile, China has chosen an opposite trajectory. During treaty negotiations, China was less proactive. It addressed certain issues, such as limiting the treaty’s scope or arguing against regional organizations joining the treaty, but Beijing avoided a leadership role. It was also one of the 22 states that abstained from voting on the adoption of the treaty at the UN General Assembly in 2013.2

Seven years later, however, China deposited its instrument of accession, in July 2020, with the treaty entering into force for Beijing in October. In August 2021, it will participate for the first time as a full member at the seventh conference of states-parties.

This development is part of a broader ongoing phenomenon regarding international institutions. The United States has stepped away from such bodies, often criticizing them with harsh language, while China has increased its involvement. The World Health Organization (WHO) offers the best example of this.3

With the relative decline of the United States and the rise of China, debates about the end of the liberal world order are also in full swing.4 It remains to be seen if the theories that claim that international institutions can effectively bind emerging powers and thus outlive the power relations of the moment of their creation will hold, particularly in this new era of revived great power comptetition.5 Yet, for the ATT, what do these shifts in the international system and developments regarding its membership mean?

The Arms Trade Treaty 1.0

As designed and adopted in 2013, the treaty pursues multiple purposes. From a normative perspective, the treaty aims to promote responsible international arms trade. This implies that its provisions set the global standards for responsible decision-making on arms transfers. The treaty’s prohibitions and arms exports provisions further aim to establish a level playing field by binding states-parties that compete in the international arms trade to the same rules. These rules are ultimately designed to foster international, regional, and state-level national security, as well as prevent human suffering. Furthermore, the ATT’s obligation to establish and maintain national control authorities enlarges the global net of national controls. In addition, the treaty fosters international cooperation, inter alia, through its reporting, international assistance mechanisms, and institutionalized meetings.

Since its entry into force, the treaty as an institution has made considerable progress. States-parties have established a treaty secretariat, meet regularly at conferences of states-parties and in working groups, and share information. Through the Voluntary Trust Fund, states-parties organize international assistance, and deliberations have led to detailed voluntary documents for the implementation of the treaty.

Since its entry into force, the treaty as an institution has made considerable progress. States-parties have established a treaty secretariat, meet regularly at conferences of states-parties and in working groups, and share information. Through the Voluntary Trust Fund, states-parties organize international assistance, and deliberations have led to detailed voluntary documents for the implementation of the treaty.

The treaty continues to grow and is now truly global, encompassing states from all continents, including many middle-sized and smaller states. It enjoys 110 states parties as well as 31 nations that have signed but not ratified. Yet the new geopolitical dynamics and shifts in U.S. and Chinese attitudes represent a critical juncture with several effects on the treaty regime and beyond.

Evolution of the Regulatory Framework

Thes most notable effect concerns the international regulatory framework of international arms transfers, namely the ATT’s legal substance and its application. These standards were negotiated and adopted in 2013 and thus are defined in the treaty. With the accession of China, the world’s fifth-largest arms exporter and importer,6 the ATT’s rules have gained relevance.

Its rules now apply to a significantly greater volume of arms transfer activities, so their impact has expanded. Besides this direct effect, the treaty has become more difficult to ignore by states that have not adhered to the ATT. It would be premature to consider the treaty as reflecting customary international law, but the Chinese accession certainly supports the emergence of such a norm as its application of the rules has considerable weight in this regard.7

China’s acceptance and application of the ATT’s rules also has an important symbolic value. This is most notable with regard to Article 6 of the treaty, which prohibits the transfer of arms that would contribute to international crimes, among others, and the obligations regarding export assessments under Article 7. By adhering to the treaty, China signals a commitment to preventing international crimes and ensuring the respect of international humanitarian law and international human rights law.

More concretely, from a legal perspective, China is now legally bound to implement and comply with the treaty’s provisions. The respective ATT standards, however, permit significant room for interpretation and allow considerable leeway for their application. Accordingly, it is difficult to assess how far the standards will affect China’s arms transfer decisions. Indeed, China has not communicated specific changes in law, policies, or practice in light of its adherence to the ATT, although it claims that a “full-fledged policy and legislative system of export control on conventional arms, which is in line with the purpose and objective of the ATT and meets the requirements of the ATT, has been established.”8

It is foreseeable, however, that China’s appreciation of the treaty’s rules will influence other nations’ understanding. States will watch how China interprets, implements, and applies the rules. China is likely to have different legal views, policies, and practices than those of the United States and European states, most notably regarding the provisions on international humanitarian law and international human rights law. This may lead other states to follow the Chinese example, ultimately transforming the treaty’s commonly understood meanings. This cannot counter the treaty text, of course, but can nonetheless be significant as many rules can be read and applied in diverse ways.

Similarly, within and through the ATT forums, China will directly influence states-parties’ individual and common understanding, as well as official guiding documents, on implementation of and compliance with the treaty. At this stage, states-parties have only adopted voluntary guiding and supporting documents that are neither legally nor politically binding. Moreover, they concern rather uncontested issues.9 As a state-party, unlike the United States, China now has the formal power to initiate, shape, and block future guidance according to its priorities. Having committed to the treaty, it also has more authority to persuade other states-parties.

Similarly, within and through the ATT forums, China will directly influence states-parties’ individual and common understanding, as well as official guiding documents, on implementation of and compliance with the treaty. At this stage, states-parties have only adopted voluntary guiding and supporting documents that are neither legally nor politically binding. Moreover, they concern rather uncontested issues.9 As a state-party, unlike the United States, China now has the formal power to initiate, shape, and block future guidance according to its priorities. Having committed to the treaty, it also has more authority to persuade other states-parties.

China has lately become more assertive in international institutions and can be expected to act more forcefully in ATT discussions. Indeed, it has already called on all states “not to provide arms to non-state actors, stop interfering in the internal affairs of sovereign states through arms sales, and earnestly abide by the purposes and principles of the UN Charter.”10 China will probably aim to embed these national priorities into the treaty’s international standards, ultimately trying to counter U.S. and European laws, policies, and practices.

Potential Conflict Between Regimes

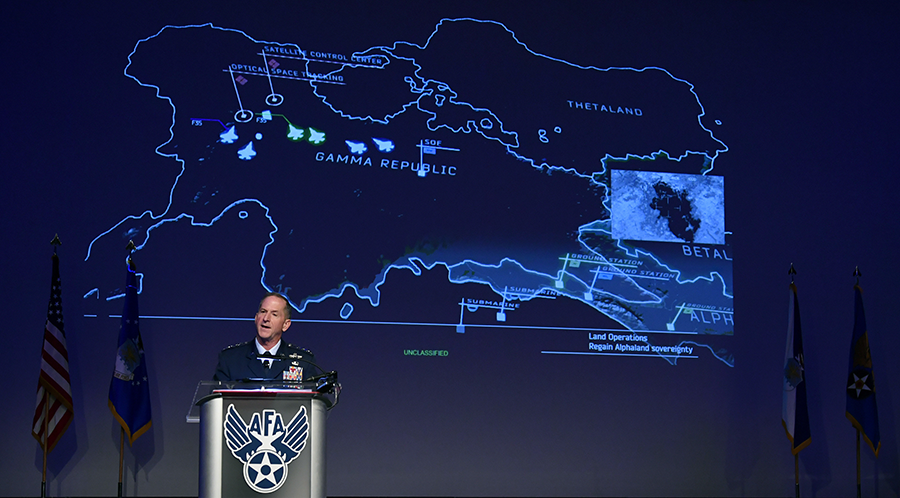

China’s treaty engagement, combined with the weakened U.S. position, affects the international institutional landscape. By revoking its signature of the treaty, the only remaining U.S. engagement in a multilateral regime on the transfer of conventional weapons is the 1996 Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. Currently, the Wassenaar Arrangement and the ATT are compatible, and there are multiple potential synergies between them.11

Wassenaar participating states, first and foremost the United States, ensured this during the ATT negotiations. The United States perceives the Wassenaar Arrangement as the “gold standard” regarding export controls and saw the ATT as a means to bring other states closer to it. Although major progress within the consensus-based Wassenaar Arrangement is currently difficult because of tensions with Russia, the United States will continue to lead that regime’s development. If China does the same with regard to the ATT, deviations between the different institutions are foreseeable.

This may result in a fragmentation of global regulations and different state practices that undermine international standards. At this point, it is difficult to identify in which direction the institutions will evolve and what sort of deviations or contradictions might emerge. Interestingly, new measures to control high technology adopted by the Wassenaar Arrangement in 2019 were reportedly aimed directly against China, among others.12 This suggests that the United States and partners already use the export control regime to counter China’s strategic goal to become a leading military power.

Within the ATT, China has already indirectly blamed the United States for rising geopolitical tensions, regional armed conflicts, and turmoil, as well as the persistence of terrorism, extremism, and organized transnational crime. It also stated that “some country, by abusing arms trade as a political tool, flagrantly interferes in the internal affairs of other countries and pursues hegemony and bullying policy, which undermines international and regional peace and stability.”13 This is indicative of the great powers using the regimes for their geopolitical goals as well as possible conflict between the regimes.

In addition, with the ATT evolving steadily and with its participation by more than the exporting states, it is quite possible that the Wassenaar Arrangement loses some of its relevance for establishing globally applicable regulatory standards. States may prefer to turn to the ATT and focus their efforts for cooperation and further developments of international regulations in this more modern, global institution.

The ATT’s broad membership, in addition to its negotiations and adoption within the United Nations, procures a high level of legitimacy to the treaty regime. The Wassenaar Arrangement, on the other hand, comprises only 42 participating states that export conventional arms and respective technologies. As such, it had been labeled an exclusive “exporters’ club” in the past.

Contrary to other emerging exporters, China has not joined the Wassenaar Arrangement. This suggests that China perceives the arrangement as illegitimate. Without U.S. balancing in the ATT, attempts to delegitimize the Wassenaar Arrangement among ATT states-parties are more likely to succeed. This would weaken not only the regime, but also the legitimacy of its members’ export control policies and decisions.

Transformation of Political Relations

The potential conflict between the thematically overlapping international institutions indicates larger political dynamics. The ATT includes many states from South America, Africa, and Asia. Indeed, the treaty addresses many of their core concerns related to international arms transfers, such as preventing and combating the diversion of arms transfers to illegal and unintended recipients or the need for capacity building and international assistance to better manage international arms transfers. ATT states-parties may see absent or weak U.S. engagement as a signal that it does not care about these issues and related multilateral cooperation.

By participating in the treaty, China communicates that it does care and is willing to cooperate and support related efforts. Indeed, by its adherence alone, China effectively enhances the relevance and impact of the ATT’s mechanisms. The diplomatic dialogue within ATT forums now includes one of the world’s major arms traders, which also happens to be a permanent member of the UN Security Council. China’s participation in the new Diversion Information Exchange Forum, for instance, adds information to the system. China’s international assistance and universalization efforts directly and indirectly benefit ATT states-parties.

China joining the ATT is also a strong signal that the ATT does not hinder the interests of major importing and emerging exporting countries. This may attract outsiders such as Russia and India, as well as hesitating Arab and Asian states, such as Malaysia and Singapore, which would strengthen the ATT even further.

The political consequence is that China now can credibly claim that it shares the same concerns as its partner states. This can facilitate political relations between China and ATT states-parties in general and regional and bilateral defense cooperation more specifically, which is in line with China’s efforts to strengthen its international ties with countries around the globe. In the context of security cooperation and arms trade, this is particularly the case regarding African states.14

Yet, the same applies to the Asia-Pacific region, where China can now present itself as a normative leader in the region regarding the control of international arms transfers. By strengthening the Asian voice in treaty forums, China can generate sympathy among states from the same region and counter the current regional leaders within the treaty regime, Japan and South Korea.

At a more general diplomatic level, as a state-party that engages in multilateral cooperation, China can present itself as a multilateralist and normative player and leader. Thereby, it gains legitimacy and the reputation of a good citizen of the international community. More specifically, China can claim that it is a responsible actor regarding the international arms trade. This arguably offers goodwill by other states and authority for its actions. Although this contributes to China’s broader foreign policy strategy to engage more actively in global affairs, this certainly applies to international diplomacy on international security issues, in particular diplomacy and cooperation on the arms trade.

Redirection of International Arms Transfers

This leads to the most practical implication of the new geopolitical developments regarding the ATT, namely their effect on the flow of arms transfers. So far, it remains uncertain if the treaty’s standards will limit China’s arms exports. Prospective changes to Chinese law, policies, and practice on arms exports will depend on other states’ pressure. Whether middle-sized and smaller states within the ATT, especially those that benefit from China’s engagement, will try to establish such pressure is highly questionable.

As a party to the treaty, China should find it easier to export weapons and related technologies. China tends not to compete for exports of technologically advanced weapons, which are generally covered by U.S., European, and Russian exports, although it has begun to export more sophisticated weapons and weapons systems, such as unmanned aerial vehicles. In any case, Chinese sales will likely be made easier now that it has joined the treaty, particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, because it is now part of the same “club” of the ATT.

Most importantly, China can now be seen as respecting and representing international standards. Importing states that are often criticized for violating international humanitarian law and international human rights law or for contributing to international and regional insecurity might gain easier access to weapons while communicating that China has applied the same standards as others.

Toward Russia, Turkey, India, and other exporting states that have rather low standards regarding international humanitarian law and human rights, this offers a competitive advantage for China. For the United States and most European countries, this reduces their leverage to bring importing states to use the imported weapons in respect to international law. They then need to decide between renouncing certain exports, thereby forgoing exports that are lucrative or in their national security interest, and lowering their own standards, which would result in a race to the bottom.

In addition, if China succeeds in establishing strong international norms against arms transfers to nonstate actors and interference in internal affairs, this may limit exports by European and other middle-sized and smaller states. Indeed, the United States is too powerful to be constrained by such norms and Chinese pressure, but not its partner states. Yet, importing states may be emboldened to reject U.S. practices for assessing their imports.

As China is not only an emerging exporter of conventional weapons but also a major importer, the fact that China is part of the ATT may facilitate its imports. As an ATT state-party, it can claim to be a responsible actor that abides by international standards. Thus, there should be fewer reasons to deny arms transfers to China. The treaty does not have a mechanism that facilitates arms transfers among state-parties, which means that the standards need to be applied to all arms transfers to all states. Yet, this still may be a valid argument, in particular when exporting states assess the risks if the importing state would reexport weapons to other states or divert them to nonstate actors. Chinese collaboration within the ATT, particularly regarding information exchange, may reassure exporters.

Most significantly, China can use the treaty’s provisions that call on exporting states to make objective and nondiscriminatory assessments to argue against their political decisions. This could affect, for example, the EU policy to suspend all arms exports to China following the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989.15

The Arms Trade Treaty 2.0

With the geopolitical shifts and in particular Chinese engagement and U.S. ambivalence, the ATT’s political center of gravity is moving from the West to the East. The international rules on arms transfers were fixed at the treaty’s adoption in 2013, but they remain malleable to a certain degree. Whether the United States has managed to lock other states, including China, into its own standards or whether China and others will own and transform these international standards remains to be seen.

Regardless, the treaty as a multilateral institution is getting stronger. The ATT’s institutional developments so far are concrete and continue to evolve. The ATT has become more relevant with such broad participation, including China. Although states-parties still prefer to avoid politically sensitive discussions on states’ international arms transfer decisions and the treaty’s prohibitions and export criteria’s concrete application, the fact that they discuss the ATT’s implementation and exchange information is significant progress. So far, the geopolitical developments have not damaged but strengthened the ATT.

Great power competition about and through the treaty regime, however, calls for caution. The biggest risk is that China will try to dominate the ATT, whereas the United States owns the Wassenaar Arrangement, and both use the respective international institutions as instruments to control other states’ arms transfers, ultimately leading to a fragmentation or even breakdown of multilateral cooperation in global arms trade. As the purpose of international institutions is to provide a focal point for cooperation and serve as platform to alleviate tensions between states, it is better if the United States joins the ATT so that the competition over influence in global affairs is fought within rather than about the ATT.

Ultimately, to secure a strong treaty, there are a number of ways states can use these geopolitical developments for advancing multilateral cooperation and law regarding the international arms trade.

The United States negotiated effectively to shape the design of the treaty. Its subsequent disengagement from the treaty has not necessarily hurt U.S. national security interests, but Washington has renounced a means to influence other states’ regulation of the arms trade. With China’s treaty accession, this renunciation weighs heavier. The only way to rebalance is the Biden administration’s revocation of the decision to “unsign” the treaty.

This alone will be inadequate because Washington has lost credibility in the international community. In addition to rejoining the agreement, the United States must seriously work to ratify the treaty. Because it does not need to change its laws, policies, or practice, it can do so at very low costs. Even if the U.S. Senate remains skeptical toward multilateral treaties, this is in the U.S. interest for geopolitical reasons. Otherwise, the United States runs the risk that its normative interests will not transcend the future.

To further rebalance the ATT toward the West, the United States must increase its engagement to higher levels than prior to its disengagement. Within the ATT forums, Washington cannot only defend the rules and common understanding that have been negotiated in 2013, but it needs to be a proactive force. By supporting ATT implementation projects and universalization efforts, it can further shape their substance and regain trust among partner states. In addition, by facilitating collaboration between the treaty and the Wassenaar Arrangement, the United States can contribute to both institutions’ efficiency and relevance. Although it has lost influence over the ATT regime, the United States can still use it as a tool to foster better control of international arms transfers around the globe and enhanced international cooperation. As such, the treaty has never been about domestic gun regulations, yet remains a means of foreign and national security policy.

For China, its engagement in the ATT means it takes responsibility for the treaty. Accordingly, Beijing should lead joint efforts for multilateral cooperation according to its own interests but also the interests of all states-parties. As a major importer and exporter state, permanent member of the UN Security Council, and leading global economy, China has significant leverage to direct the ATT regime toward achieving the treaty’s purpose. For this to materialize, however, it is crucial that China does not just defend its own narrow interests. It should not seek to use the treaty as a diplomatic tool against the United States. Rather, China should engage in constructive dialogue with other ATT states-parties, as well as assist their implementation efforts.

For the other ATT states-parties, it is important to integrate China in the joint work so that it can rapidly engage and collaborate. Most importantly, states should work closely with China to ensure that it upholds the treaty’s current standards. European states and the European Union, as normative forces and strong supporters of ATT-related capacity building, have an important role in this.

Major exporters, such as France and the United Kingdom, should constructively contribute to the treaty’s progress rather than try to avoid criticism against their practices by diverting the focus to China’s actions. Civil society organizations, in particular Control Arms, which publishes the annual ATT Monitor, are essential to ensure the right focus in this regard. As international cooperation involves more than one party, all ATT states-parties should invest in getting the United States on board.

Conclusion

The ATT is the object and scene of the U.S. and Chinese competition for influence in global security affairs. This will most likely affect the treaty regime, the international institutional landscape, states’ political relations, and transnational arms flows. As such, the geopolitically induced shifts regarding the ATT may be a first example of a broader tendency in multilateral disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation. At least for the ATT and the international regulation of transnational arms transfers, these shifts must not mean the end or weakening of multilateralism, multilateral cooperation, or multilateral law. Rather, these shifts signify a continuation and reinforcement of multilateralism with potential reorientation of its substance.

Yet, what appear to be slow and fluid changes in international affairs may actually be significant breaking points. It is up to all ATT states-parties to ensure that the new geopolitics advance mutual benefits. The relocation of the ATT’s political center of gravity from the West to the East has occurred. Even if the United States recommits, the power balance within the treaty regime is novel. Any level of U.S. reengagement would strengthen the treaty, even if great power competition makes it a contested regime.

Indeed, the ATT version 2.0 has already started. As part of a broader phenomenon, this may indicate what will come with regard to other international institutions and multilateral security cooperation. The new geopolitics of the ATT may represent a new era of multilateralism.

ENDNOTES

1. A formal “unsigning” of international treaties does not exist under international law. Jeff Abramson and Greg Webb, “U.S. to Quit Arms Trade Treaty,” Arms Control Today, May 2019.

2. Anna Stavrianakis and He Yun, “China and the Arms Trade Treaty: Prospects and Challenges,” Saferworld, May 2014, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/180595/china-and-the-att.pdf.

3. See, e.g., Harod H. Koh and Lawrence O. Gostin, “How to Keep the United States in the WHO,” Foreign Affairs, June 5, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-05/how-keep-united-states-who; Hinnerk Feldwisch-Drentrup, “How WHO Became China’s Coronavirus Accomplice,” Foreign Policy, April 2, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/02/china-coronavirus-who-health-soft-power/.

4. See, e.g., G. John Ikenberry, “The Next Liberal Order: The Age of Contagion Demands More Internationalism, Not Less,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-06-09/next-liberal-order; Richard N. Haass, “Liberal World Order, R.I.P.,” Project Syndicate, March 21, 2018, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/end-of-liberal-world-order-by-richard-n--haass-2018-03?barrier=accesspaylog.

5. See G. John Ikenberry, After Victory (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Robert Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

6. Pieter D. Wezeman et al., “Trends in International Arms Transfers 2019 Fact Sheet,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2020, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/fs_2003_at_2019.pdf.

7. U.S. practice is compatible with the Arms Trade Treaty and can contribute to the emergence of relevant practice.

8. Permanent Mission of the People's Republic of China to the UN Office at Geneva and Other International Organizations in Switzerland, “Statement of the People's Republic of China to the Sixth Conference of States-Parties to the Arms Trade Treaty,” August 17, 2020, http://www.china-un.ch/eng/dbtxwx/t1807021.htm.

9. For the documents, see Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), “Tools and Guidelines,” n.d., https://thearmstradetreaty.org/tools-and-guidelines.html (accessed November 9, 2020).

10. Chinese statement to ATT conference of states-parties, August 17, 2020.

11. Tobias Vestner, “Synergies Between the Arms Trade Treaty and the Wassenaar Arrangement,” GCSP Strategic Security Analysis, No. 5 (May 2019), https://dam.gcsp.ch/files/2y102vjaRJo9CCUZAgCU2XP0YequIEZV5wodwIppHEGiOXu8bstaN1Qxu.

12. “Arms-Curbing Wassenaar Arrangement Agrees to Add Military-Grade Software and Chip Tech to Export Control List,” Kyodo News, February 24, 2020.

13. Chinese statement to ATT conference of states-parties, August 17, 2020.

14. Bernardo Mariani, “China, Africa, and the Arms Trade Treaty,” in China and Africa: Building Peace and Security Cooperation on the Continent, ed. Chris Alden et al. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), pp. 333–354.

15. European Council, “Presidency Conclusions,” SN/254/2/89, n.d. (Annex II, Declaration on China, from meeting in Madrid on June 26–27, 1989).

Tobias Vestner is head of the Security and Law Programme at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, an honorary senior research fellow at the University of Exeter, and nonresident fellow at the UN Institute for Disarmament Research. He co-authored A Guide to International Disarmament Law (2019) and was member of the Swiss delegation to the Arms Trade Treaty negotiations.

Although the new interceptor, known as the Aegis Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block IIA, may help mitigate the ballistic missile threat from North Korea in the near term, it will undoubtedly encourage Russia and China to believe they need to continue to enhance the capability and quantity of their offensive nuclear-armed missiles—and undoubtedly complicate progress on arms control.

Although the new interceptor, known as the Aegis Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block IIA, may help mitigate the ballistic missile threat from North Korea in the near term, it will undoubtedly encourage Russia and China to believe they need to continue to enhance the capability and quantity of their offensive nuclear-armed missiles—and undoubtedly complicate progress on arms control.

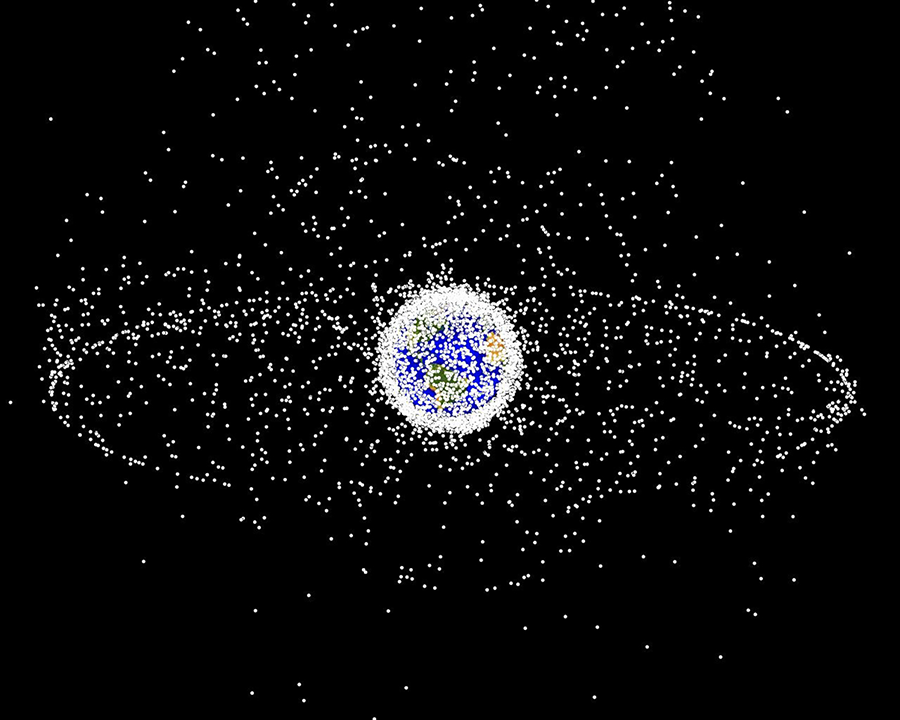

Doing so will not be easy. Space is a unique domain, with its own physical, legal, and political dynamics. Hardly any of the work necessary to develop the conceptual foundations for space arms control has been done, let alone to define how to meet the conditions for measures that are equitable and verifiable and enhance U.S. national security as laid out in current U.S. policy. All of these, however, are challenges that should be overcome, not insurmountable obstacles, because ensuring the long-term sustainability and security of space for the benefit of all is an end result too important to ignore.

Doing so will not be easy. Space is a unique domain, with its own physical, legal, and political dynamics. Hardly any of the work necessary to develop the conceptual foundations for space arms control has been done, let alone to define how to meet the conditions for measures that are equitable and verifiable and enhance U.S. national security as laid out in current U.S. policy. All of these, however, are challenges that should be overcome, not insurmountable obstacles, because ensuring the long-term sustainability and security of space for the benefit of all is an end result too important to ignore. The vast majority of legally binding proposals on space security have emerged within the Conference on Disarmament (CD), which has had an agenda item on the prevention of an arms race in outer space since the 1980s.

The vast majority of legally binding proposals on space security have emerged within the Conference on Disarmament (CD), which has had an agenda item on the prevention of an arms race in outer space since the 1980s. Second, although many countries will need to play a role in resolving these challenges, the United States must take a leadership role. The United States is still the most powerful country in space and has the most to lose, should space devolve into an arena of unrestrained weaponization and potential armed conflict. Preventing this exact outcome was part of the impetus that drove the United States to play a major role in creating the current international legal regime in space, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, that has served the United States and the world so well.

Second, although many countries will need to play a role in resolving these challenges, the United States must take a leadership role. The United States is still the most powerful country in space and has the most to lose, should space devolve into an arena of unrestrained weaponization and potential armed conflict. Preventing this exact outcome was part of the impetus that drove the United States to play a major role in creating the current international legal regime in space, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, that has served the United States and the world so well. Countries and special interest groups hostile to the concept of space arms control often assert that it is impossible to verify space weapons and therefore space arms control is not feasible. That is true to a point: it is extremely difficult to determine whether a satellite is a weapon, in large part because there are many ways that a satellite can be used for weapons effects. This assertion, however, hides two things. It is possible to verify many types of actions in space, such as a close approach of another object or a collision that generates large amounts of orbital debris. Also, it is more difficult to use a satellite to harm another satellite than often postulated, and militaries are much more likely to choose custom-designed weapons to achieve desired effects than try to modify a commercial or civil satellite.

Countries and special interest groups hostile to the concept of space arms control often assert that it is impossible to verify space weapons and therefore space arms control is not feasible. That is true to a point: it is extremely difficult to determine whether a satellite is a weapon, in large part because there are many ways that a satellite can be used for weapons effects. This assertion, however, hides two things. It is possible to verify many types of actions in space, such as a close approach of another object or a collision that generates large amounts of orbital debris. Also, it is more difficult to use a satellite to harm another satellite than often postulated, and militaries are much more likely to choose custom-designed weapons to achieve desired effects than try to modify a commercial or civil satellite. Originally, the United States, the world’s largest arms exporter, supported and significantly shaped the treaty negotiations. Washington aimed to encourage other nations to better regulate international arms transfers in line with U.S. standards. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry signed the treaty in September 2013, but domestic politics prevented the Obama administration from ratifying the agreement. Nonetheless, the U.S. signature signaled its commitment to other states and enabled Washington to engage in many of the treaty’s activities.

Originally, the United States, the world’s largest arms exporter, supported and significantly shaped the treaty negotiations. Washington aimed to encourage other nations to better regulate international arms transfers in line with U.S. standards. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry signed the treaty in September 2013, but domestic politics prevented the Obama administration from ratifying the agreement. Nonetheless, the U.S. signature signaled its commitment to other states and enabled Washington to engage in many of the treaty’s activities. Since its entry into force, the treaty as an institution has made considerable progress. States-parties have established a treaty secretariat, meet regularly at conferences of states-parties and in working groups, and share information. Through the Voluntary Trust Fund, states-parties organize international assistance, and deliberations have led to detailed voluntary documents for the implementation of the treaty.

Since its entry into force, the treaty as an institution has made considerable progress. States-parties have established a treaty secretariat, meet regularly at conferences of states-parties and in working groups, and share information. Through the Voluntary Trust Fund, states-parties organize international assistance, and deliberations have led to detailed voluntary documents for the implementation of the treaty. Similarly, within and through the ATT forums, China will directly influence states-parties’ individual and common understanding, as well as official guiding documents, on implementation of and compliance with the treaty. At this stage, states-parties have only adopted voluntary guiding and supporting documents that are neither legally nor politically binding. Moreover, they concern rather uncontested issues.

Similarly, within and through the ATT forums, China will directly influence states-parties’ individual and common understanding, as well as official guiding documents, on implementation of and compliance with the treaty. At this stage, states-parties have only adopted voluntary guiding and supporting documents that are neither legally nor politically binding. Moreover, they concern rather uncontested issues. During World War I, for example, Germany exploited advances in chemical production to develop asphyxiating gases for military use, provoking widespread public outrage and prompting postwar efforts to ban such munitions. During World War II, the United States exploited advances in nuclear science to create the atomic weapons used against Japan, again generating public outrage and prompting postwar control efforts. Today, rapid advances in a range of scientific and technological fields—artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, cyberspace, remote sensing, and microelectronics—are again being exploited for military use. And, as before, control efforts are lagging far behind the process of weaponization.

During World War I, for example, Germany exploited advances in chemical production to develop asphyxiating gases for military use, provoking widespread public outrage and prompting postwar efforts to ban such munitions. During World War II, the United States exploited advances in nuclear science to create the atomic weapons used against Japan, again generating public outrage and prompting postwar control efforts. Today, rapid advances in a range of scientific and technological fields—artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, cyberspace, remote sensing, and microelectronics—are again being exploited for military use. And, as before, control efforts are lagging far behind the process of weaponization. Second, multiple strikes by hypersonic missiles could be used early in a conflict to destroy key enemy assets like those described above, again causing the target state to fear that a nuclear strike is imminent and cause it to launch its own nuclear arms. This danger is multiplied by the fact that the flight time of hypersonic missiles is extremely brief and that many of these weapons now being developed by the major powers are designed to carry a nuclear or a conventional warhead, leaving a target country in doubt as to an attacker’s ultimate intentions, especially if key C3I facilities are degraded, preventing senior leaders from knowing the nature of the attack and inclining them to assume the worst.

Second, multiple strikes by hypersonic missiles could be used early in a conflict to destroy key enemy assets like those described above, again causing the target state to fear that a nuclear strike is imminent and cause it to launch its own nuclear arms. This danger is multiplied by the fact that the flight time of hypersonic missiles is extremely brief and that many of these weapons now being developed by the major powers are designed to carry a nuclear or a conventional warhead, leaving a target country in doubt as to an attacker’s ultimate intentions, especially if key C3I facilities are degraded, preventing senior leaders from knowing the nature of the attack and inclining them to assume the worst. “Today, pursuant to earlier notice provided, the United States withdrawal from the Treaty on Open Skies is now effective,” said Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in a tweet. “America is more secure because of it, as Russia remains in noncompliance with its obligations.”

“Today, pursuant to earlier notice provided, the United States withdrawal from the Treaty on Open Skies is now effective,” said Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in a tweet. “America is more secure because of it, as Russia remains in noncompliance with its obligations.” In May 2018, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed sanctions on Iran. (See

In May 2018, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed sanctions on Iran. (See  The latest quarterly report describes these ongoing JCPOA breaches and suggests that Iran is moving carefully to avoid steps that could impede a U.S. reentry to the nuclear deal or its own future return to full compliance with the accord. The Trump administration withdrew from the deal in 2018, and Iran has subsequently exceeded a number of the agreement’s limitations.

The latest quarterly report describes these ongoing JCPOA breaches and suggests that Iran is moving carefully to avoid steps that could impede a U.S. reentry to the nuclear deal or its own future return to full compliance with the accord. The Trump administration withdrew from the deal in 2018, and Iran has subsequently exceeded a number of the agreement’s limitations. The sales appear to be linked to the August agreement in which the UAE and Israel normalized relations, with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo noting in his Nov. 10 announcement of the proposed sales that the “historic agreement to normalize relations with Israel under the Abraham Accords offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to positively transform the region’s strategic landscape.”

The sales appear to be linked to the August agreement in which the UAE and Israel normalized relations, with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo noting in his Nov. 10 announcement of the proposed sales that the “historic agreement to normalize relations with Israel under the Abraham Accords offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to positively transform the region’s strategic landscape.” Complying with pandemic limits prohibiting meetings of more than 50 people in Geneva, parties to the 164-nation treaty met virtually to continue their efforts to rid the world of antipersonnel landmines. Nearly 500 participants registered for the meeting, including government representatives from 88 states-parties and 11 states not party to the treaty.

Complying with pandemic limits prohibiting meetings of more than 50 people in Geneva, parties to the 164-nation treaty met virtually to continue their efforts to rid the world of antipersonnel landmines. Nearly 500 participants registered for the meeting, including government representatives from 88 states-parties and 11 states not party to the treaty.