December 2023

By Sharon Squassoni

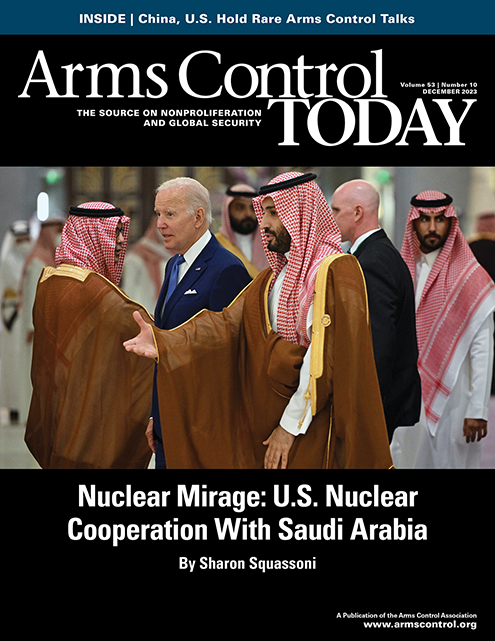

Before the violent attack by Hamas on Israel in the early morning hours of October 7, Israel and Saudi Arabia had been inching toward a bilateral agreement on normalizing relations, reportedly brokered by the United States.

For the Middle East, this could have had huge implications for peace, security, and cooperation akin to those of the 1978 Camp David Accords. The rumors began circulating in August that the United States was not just brokering the agreement but would provide security guarantees, access to military technology, and civilian nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia to sweeten the deal.1 By September, Saudi officials announced a long-awaited step to upgrade implementation of their comprehensive nuclear safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). This step, fully implementing comprehensive inspections, would be the bare minimum requirement for any significant nuclear cooperation between Saudi Arabia and the United States.

For the Middle East, this could have had huge implications for peace, security, and cooperation akin to those of the 1978 Camp David Accords. The rumors began circulating in August that the United States was not just brokering the agreement but would provide security guarantees, access to military technology, and civilian nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia to sweeten the deal.1 By September, Saudi officials announced a long-awaited step to upgrade implementation of their comprehensive nuclear safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). This step, fully implementing comprehensive inspections, would be the bare minimum requirement for any significant nuclear cooperation between Saudi Arabia and the United States.

The details of this deal are still murky, but press reports suggest that the United States was considering supplying the kingdom with a uranium-enrichment facility that the United States would control.2 It is not clear whether the Saudis or the United States would own the facility or whether there was a plan to establish multilateral control over the plant.

The need for control in addition to monitoring the plant’s operation and output is essential because uranium-enrichment plants are inherently dual use: they can prepare uranium to fuel nuclear research and power reactors or to be used as the fissile material in an atomic bomb. In the case of Iran, its secret construction of uranium-enrichment facilities led the international community first to sanction the country, then to negotiate limits on its use of that technology. Saudi Arabia repeatedly has declared since 2011 that it would match Iran’s capabilities.

Nuclear cooperation often has been promised by the United States to allies for far fewer returns but never with such obviously high proliferation risks.3 First, the United States is offering nuclear latency to a country that basically has said “all bets are off” if a regional competitor, Iran, proliferates. Second, the United States is no closer to reining in Iran’s nuclear program, which increases the risk of a proliferation cascade. Third, a decision by the United States to build a uranium-enrichment plant in Saudi Arabia would undermine two important U.S. nonproliferation policies: a global policy not to spread uranium-enrichment or spent fuel reprocessing technology to any additional countries and a regional policy to maintain equal terms and conditions for nuclear cooperation with partners in the Middle East.

The war in Gaza has forced a postponement of the broader normalization agreement and, hopefully, the scheme of supplying Saudi Arabia with its own uranium-enrichment capabilities. It raises questions, however, about what exactly the United States is trying to achieve through its nuclear cooperation policies.

A Short History of Nuclear Cooperation

Even as radioactive fallout was settling over Nagasaki, U.S. President Harry S. Truman announced that the United States would seek the means “to control the bomb so as to protect ourselves and the rest of the world from the danger of total destruction.” In his radio address on August 9, 1945, he told Americans that he would instruct Congress “to cooperate to the end that [nuclear weapons] production and use would be controlled, and that its power be made an overwhelming influence towards world peace.”4

International control of nuclear weapons would never materialize, and neither would international control of peaceful nuclear energy. The 1946 Baruch Plan, proposed by the United States, allowed for the destruction of U.S. nuclear weapons only after strict control of all nuclear assets under an international Atomic Development Authority ensured there would be no other proliferation of nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union and Poland, fearing a U.S. nuclear monopoly, abstained from voting on the plan in the UN Security Council, where it failed. As diplomacy faltered, nuclear weapons development continued. In just a few years, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom tested nuclear weapons.

Against this backdrop, the December 8, 1953, speech by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly that launched the “Atoms for Peace” program seems odd. Whether a Cold War propaganda effort or a genuine attempt to allay human fears by suggesting that peaceful uses of the atom could balance military destruction by the atom, the speech heralded a sea change in the U.S. approach. Shifting from strictly guarding all things nuclear, the United States began encouraging access to information, material, and nuclear technology for peaceful uses. Over the next four years, the United States overhauled its laws to allow nuclear cooperation, promoted a 1955 international conference in Geneva showcasing nuclear technology, and helped create the IAEA in 1957, more than 10 years before countries banded together to negotiate and sign the landmark nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) that was designed to halt the nuclear arms race and the spread of nuclear weapons.5

For nuclear cooperation, the 1954 revision of the Atomic Energy Act was pivotal. It called for “a program of international cooperation to promote the common defense and security and to make available to cooperating nations the benefits of peaceful applications of atomic energy as widely as expanding technology and considerations of the common defense and security will permit.”6 The amended law allowed for both military nuclear cooperation and peaceful nuclear cooperation. On the peaceful side, the scope of activities included civilian reactor development, production of special nuclear material, and non-electricity industrial applications, as well as research and development. Within a little more than a decade, the United States signed 34 bilateral agreements, two-thirds of which were strictly for research.7

The United States sought to achieve specific foreign policy aims through nuclear cooperation. A 1955 National Security Council report declared that

U.S. determination to promote the peaceful uses of atomic energy, with calculated emphasis on a peaceful atomic power program abroad as well as at home, can generate free world respect and support for the constructive purposes of U.S. foreign policy. Such a program will strengthen American world leadership and disprove the communists’ propaganda charges that the U.S. is concerned solely with the destructive uses of the atom. Atomic energy, which has become the foremost symbol of man’s inventive capacities, can also become the symbol of a strong but peaceful and purposeful America.8

The report gave a nod to preventing the diversion of nonpeaceful uses of any fissile material provided to other countries, but required just two conditions: reprocessing in U.S. facilities or under international arrangements and “the adequate provision of production accounting, inspection, and other techniques” largely not yet devised.

The program promoting nuclear cooperation boldly envisioned a range of technical and financial assistance to foreign countries for research and power reactors, including the design of small reactors specifically for export, continued declassification of reactor technology, and transfer of material. In particular, it urged that cooperation agreements should “seek opportunities for maximum U.S. cooperation in those power reactor projects abroad which offer political and psychological advantages.”

It is fair to say that the United States overreached with the Atoms for Peace program. After sending more than 25 tons of highly enriched uranium overseas as fuel for research reactors, the United States spent millions of dollars and decades trying to get the material back because it belatedly realized that the material posed nuclear security risks. A few early projects, such as those in the Philippines and Brazil, were failures.9 The United States ceased to fund nuclear energy projects with foreign assistance funds by 1960, and although research reactors spread widely, nuclear power did not spread quickly.

For some states, however, assistance for research capabilities helped provide the initial basis of clandestine nuclear weapons programs. By the mid-1970s, it was apparent that nuclear trade needed to be restrained because several countries, including Brazil, Pakistan, and South Korea, were intent on acquiring sensitive nuclear fuel-cycle facilities from foreign suppliers. The United States and other key countries advocated for greater restraint in nuclear trade, establishing the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and tightening national export controls.

In 1974 the Ford administration adopted the first restraint policy in the transfer of sensitive nuclear technology and facilities, prohibiting export of reprocessing and other nuclear technologies, firmly opposing reprocessing in South Korea and Taiwan, and negotiating agreements for cooperation with Egypt and Israel that contained “the strictest reprocessing provisions.”10 In his 1976 statement on nuclear policy, President Gerald Ford called on all nations to join the United States “in exercising maximum restraint in the transfer of reprocessing and enrichment technology and facilities by avoiding such sensitive exports or commitments for a period of at least three years.”11

Almost 30 years later, President George W. Bush called for a similar moratorium in reaction to revelations about the black market transfers to North Korea, Iran, and Libya by Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan. A U.S. policy of restraint has endured despite the fact that the Atomic Energy Act itself does not prohibit sharing of enrichment and reprocessing technologies.

Nuclear Energy in the Middle East

Nuclear power has been slow to establish a firm footing in the Middle East. Early nuclear cooperation agreements signed by the United States with Israel, Iran, and Lebanon from 1955 to 1964 focused on nuclear research rather than nuclear power. In 1980 and 1981, the United States signed agreements with Morocco and Egypt, respectively.

Undoubtedly, Egypt’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel opened the door to other normalization steps by Egypt, including ratification of the NPT and adoption of a full-scope safeguards agreement as the treaty requires. These developments were especially timely because the passage of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act in 1978 moved the goalposts for Egypt by requiring these steps before nuclear cooperation with the United States was permissible.12 Today, after many delays, Egypt is just beginning construction of two Russian nuclear power reactors.

The history of countries in the Middle East with clandestine nuclear activities (Iran, Iraq, Israel, Libya, and Syria) is well known, and regional rivalries amplify concerns. In 2007 the Gulf Cooperation Council states explored the possibility of a regional nuclear power effort, but by 2009, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia each decided to develop nuclear energy on their own. At the time, Iran’s nuclear activities were a significant concern. Whereas the UAE, in launching its nuclear energy program, understood the need to allay international concerns about nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia seems impervious. In contrast to the UAE’s public renunciation of uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing, Saudi Arabia has declared explicitly that it would match Iran’s capabilities, including nuclear weapons.

The Saudis have been relative latecomers to nuclear energy or at least slow to implement their plans, compared especially to the UAE. After establishing the King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy in Riyadh in 2010, Saudi officials announced their intention to construct 16 nuclear reactors to generate 20 percent of the kingdom’s electricity by 2032. In 2017, the Saudi National Atomic Energy Project declared that its civil nuclear program would feature large nuclear power plants, small modular reactors, and fuel cycle activities. Initially, Saudi fuel-cycle activities were limited to assessing uranium and thorium reserves and yellowcake production with Jordan.13

![Saudi Minister of Energy Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman al-Saud speaks at a conference in Riyadh in June, six months after he declared that the kingdom “wants the entire [nuclear] fuel cycle.” (Photo by Fayez Nureldine/AFP via Getty Images)](/sites/default/files/images/ACT_Photos/2023_12/2_ACT_Dec2023_Feature_Saudi_al-Saud.png) In January 2023, Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman told a local mining conference that Riyadh wants “the entire nuclear fuel cycle, which involves the production of yellowcake, low-enriched uranium, and the manufacturing of nuclear fuel both for our national use and of course for export.”14 At the same time, the Saudis are only slowly moving ahead with small modular reactor projects and now estimate they will procure just two large nuclear power reactors. Their interest in fuel cycle capabilities seems disproportionate to a scaled-back nuclear energy program.

In January 2023, Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman told a local mining conference that Riyadh wants “the entire nuclear fuel cycle, which involves the production of yellowcake, low-enriched uranium, and the manufacturing of nuclear fuel both for our national use and of course for export.”14 At the same time, the Saudis are only slowly moving ahead with small modular reactor projects and now estimate they will procure just two large nuclear power reactors. Their interest in fuel cycle capabilities seems disproportionate to a scaled-back nuclear energy program.

Saudi Arabia signed a memorandum of understanding with the United States in 2008 as a prelude to a nuclear cooperation agreement. The text stated the Saudi “intent to rely on existing international markets for nuclear fuel services as an alternative to the pursuit of enrichment and reprocessing.”15 Since then, official negotiations with the United States have been sporadic. In 2020, U.S. officials revealed that the United States had asked specifically for Saudi Arabia to sign an additional protocol to its IAEA safeguards agreement, which allows for more intrusive IAEA inspections of nuclear facilities, and for restrictions on enrichment and reprocessing.

In testimony last spring, U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration Administrator Jill Hruby told the Senate Armed Services Committee that the United States has asked the Saudis “to be consistent with nonproliferation standards that we have for every other country that we work with.”16 Meanwhile, between 2011 and 2016 the Saudis signed arrangements with France, South Korea, Argentina, Russia, China, and Kazakhstan. Some of these projects have already begun training programs for Saudi nuclear workers.

Providing a U.S.-owned and likely U.S.-operated enrichment plant on Saudi soil might be politically more palatable than a national Saudi plant, especially since the size of the Saudi nuclear program does not justify domestic enrichment. NSG guidelines state that suppliers “should encourage recipients to accept, as an alternative to national plants, supplier involvement and/or other appropriate multinational participation in resulting facilities.”17 For actual transfers, NSG guidelines require the recipient to bring into force a comprehensive nuclear safeguards agreement and an additional protocol, which the United States requires as a matter of policy.

A fallback option for Saudi Arabia would be to purchase equity in a foreign enrichment company such as Orano, but this may be unattractive because of Iran’s historically negative experience investing in Eurodif. The Saudis likely would not want to risk a similar fate.

In addition to political hurdles, the technical hurdles of building a new centrifuge plant in Saudi Arabia could be considerable. The case of URENCO’s plant in Eunice, New Mexico, may be instructive. URENCO, an international fuel-cycle service supplier, did not transfer its technology to the United States and required specific procedures to guard against technology transfer. That said, the status of the United States as a nuclear-weapon state made certain processes less difficult, such as hiring U.S. workers with requisite security clearances in the construction phase.

Nonetheless, it still took 10 years between the licensing at the outset of the project and the operation of the first cascades in New Mexico. If the United States were to build a plant for the Saudis, it likely would have to use U.S. centrifuge technology. Yet, Centrus, the U.S. supplier of nuclear fuel and services for the nuclear power industry, currently is operating only a demonstration cascade in Piketon, Ohio, under a U.S. government contract and has not scaled its new technology for the commercial market.18

A plan to build a multinational facility, perhaps with the cooperation of URENCO, might overcome some of the hesitance among NSG members, but the experience of multinational fuel-cycle facilities is not entirely promising. For example, Eurochemie, the multinational reprocessing plant in Belgium, made no effort to compartmentalize knowledge among its international workforce, and URENCO allowed each country involved in the project (Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) to develop its own technology before choosing one.

Finally, URENCO Netherlands was the source of much technology for the Khan nuclear black market network. Although there have been many proposals, including from governmental experts and the IAEA, to multilateralize fuel cycle facilities with the objective of diminishing national control of sensitive fuel-cycle capabilities, these usually assume that the benefits will outweigh the risks. The historical evidence, however, is mixed.

Finally, URENCO Netherlands was the source of much technology for the Khan nuclear black market network. Although there have been many proposals, including from governmental experts and the IAEA, to multilateralize fuel cycle facilities with the objective of diminishing national control of sensitive fuel-cycle capabilities, these usually assume that the benefits will outweigh the risks. The historical evidence, however, is mixed.

Possible Outcomes

The United States has been courting Saudi officials for 15 years on negotiating a nuclear cooperation agreement, with little to show for it. Few nuclear deals have taken so much time to negotiate as this one, and it is still far from finished. Some agreements, such as the first civil nuclear cooperation agreement between the United States and China, were relatively quick to negotiate but then languished before Congress because of proliferation concerns. Others, such as the U.S. agreement with South Korea, were extended provisionally to provide more time to negotiate delicate details where interests diverged.

To conclude a nuclear cooperation agreement, the United States almost certainly will need Saudi Arabia to sign an additional protocol to its comprehensive safeguards agreement. The kingdom may chafe at this because Iran does not have an additional protocol in force. Other past requests of Riyadh by Washington, such as forswearing enrichment, may be particularly difficult to achieve in the current environment if press reports are accurate. It also carries a risk: If Saudi Arabia forswears enrichment in an agreement with the United States and then procures the capability from other states, the U.S. agreement likely would be terminated. Sanctions likely would follow.

A decision to allow Saudi Arabia to go forward with uranium enrichment, on the other hand, would overturn decades of U.S. policy. The United States has never sold uranium-enrichment or spent fuel reprocessing plants to any country and has led the campaign within the nuclear nonproliferation regime for almost 50 years to prevent such sales globally. Moreover, the United States rarely grants other countries its consent to enrich or reprocess U.S.-origin nuclear material even if they use their own capabilities.

The United States has been adamant about seeking assurances from partners, particularly in the Middle East, that they will not enrich or reprocess, notably in a 1981 nuclear cooperation agreement with Egypt and a 2009 agreement with the UAE. In return, Washington promised in those agreements that it would not grant more favorable terms to other partners in the region. If the United States provided such capabilities to Saudi Arabia, it would face pressure from the UAE and, in the future, Jordan and likely South Korea to provide the same.

Some may argue that if the United States does not supply Saudi Arabia with enrichment capabilities, China or Russia might be willing to supply them. This ignores the fact that NSG guidelines state a preference for avoiding the spread of national capabilities and that the NSG operates by consensus. Russia, which supplies Iran with nuclear fuel, may not desire to supply Saudi Arabia with enrichment capabilities.

Even without a uranium-enrichment plant on offer, approval of a nuclear cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia could be contentious in the United States, given the kingdom’s poor human rights record and its frequent statements regarding its intentions to pursue nuclear weapons. It will likely be tough for members of Congress to ignore the brutal dismemberment in 2018 of U.S. journalist Jamal Khashoggi, which the CIA blamed on Riyadh. Although the bar is set rather high for Congress to disapprove a nuclear cooperation agreement that has been finalized by a U.S. president, there are still ways for determined lawmakers to delay, derail, and block implementation of the deal until policy goals are satisfied.

Nuclear cooperation agreements, like nuclear energy, carry inherent risks. As vehicles for transferring technology, material, and equipment that can serve peaceful and military uses, such agreements must balance the competing objectives of facilitating engagement without increasing proliferation risk. Their use in cementing strategic relationships often can come into conflict with their basic purpose of delineating the substance and methods of collaboration. The more important the relationship is in terms of commercial, political, and security needs, the greater the pressure there is to adjust the balance of obligations toward engagement. The U.S. government at times has used nuclear cooperation agreements to create strategic alliances, as with India, or to bolster existing alliances, as with Japan and South Korea. With Saudi Arabia, nuclear cooperation seems oriented toward fending off rising competition from China and Russia.

Risks tend to rise when special deals for special allies undermine principled stands. In the last 20 years, two major U.S. principles have been breached: a ban on nuclear trade with countries that had not signed the NPT and a refusal to share nuclear-fueled submarines beyond cooperation with the UK. The United States rationalized both of these exceptions—nuclear cooperation with India and the sale of U.S. nuclear-powered submarines to Australia—by arguing the need to compete strategically with China.

It may be that China’s role in brokering an agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran on the war in Yemen helped push Israel and the United States to concoct this trilateral peace-for-arms-and-nuclear-latency deal with Saudi Arabia. It is no secret that China already has provided nuclear assistance to Saudi Arabia and Iran in uranium processing in the form of uranium conversion and uranium hexafluoride production, respectively. More recently, China has proposed building nuclear power reactors for Saudi Arabia.19 The United States was able to dissuade China in the 1990s from making such sales, but since then, China has made nuclear exports a foreign policy objective, much as Russia has done.

What stands out especially about the Saudi nuclear deal is the willful refusal of U.S. officials to acknowledge the kingdom’s overt proliferation intentions. Saudi officials have insisted since 2011 that they will acquire whatever capabilities Iran has. This should be a red flag for any country providing nuclear technology purely for peaceful purposes. No deal should move forward until Saudi Arabia commits to using nuclear technology solely for peaceful purposes regardless of what Iran does.

The Camp David Accords led the way to a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt in 1979. The United States began negotiating with Egypt in 1979, but only after Egypt signed a comprehensive safeguards agreement in 1981 could the United States complete a nuclear cooperation agreement. Although Egypt had plans to reprocess spent fuel and had been courting Russia, it agreed to put those ambitions on hold and consented to language that specified it would not conduct reprocessing on its soil.

Egypt’s welcome into the nuclear fold took a few years and contained more restrictions than it perhaps desired. In the case of Saudi Arabia, the United States apparently was prepared to put the kingdom on the fast track toward a latent nuclear capability, matching or perhaps exceeding Iran’s enrichment capabilities. Even if the United States owned and operated the enrichment plant, there would be no guarantees against Saudi nationalization in a time of crisis.

Saudi Arabia faces no legal barriers to building a uranium-enrichment facility on its soil if it is prepared to accept full-scope safeguards, but it does face policy barriers. No matter what, the kingdom will have to adopt an additional protocol to its comprehensive safeguards agreement if it would like to receive enrichment technology and equipment from a country that is an NSG member. Outside the NSG, North Korea and Pakistan are potential suppliers, but this scenario is unlikely. Clandestine help likely would be detected, and transparent help would place Pakistani and North Korean technology under monitoring, something that neither supplier would welcome.

It might be possible for Saudi Arabia to receive enrichment technology from other NSG suppliers, but Saudi Arabia, like the UAE, probably has judged that U.S. approval is helpful to allay proliferation concerns, effectively conferring a “Good Housekeeping” seal of approval. The kingdom does not particularly desire U.S. nuclear reactor sales. In fact, because U.S. dominance in nuclear technology exports has been on the decline for a very long time, U.S. influence is now largely sought as a means of enlisting the cooperation of other states that can build nuclear power plants abroad quickly and cheaply, such as South Korea.

U.S. officials should keep in mind, however, that the United States still is a leader in promoting nonproliferation, nuclear safety, and nuclear security standards and that deviating from key principles, such as opposing the spread of sensitive fuel-cycle capabilities, will only reduce its influence.

More broadly, the United States should embrace the possibility that normalization of relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia is possible without nuclearization and look to bestow other key benefits on the kingdom in exchange for a regional peace that would truly reflect democratic and sustainable development goals.

ENDNOTES

1. Dion Nissenbaum, “Saudis Agree With U.S. on Path to Normalize Kingdom’s Ties With Israel,” The Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2023.

2. Dion Nissenbaum and Dov Lieber, “Israel Mulls Accepting Saudi Nuclear Enrichment,” The Wall Street Journal, September 21, 2023.

3. It could be argued that the U.S. nuclear cooperation agreements with Russia, China, and India contain security risks, but because these are all states with nuclear weapons, they would not strictly constitute proliferation risks.

4. “August 9, 1945: Radio Report to the American People on the Potsdam Conference; Transcript,” Miller Center, n.d., https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/august-9-1945-radio-report-american-people-potsdam-conference (accessed November 21, 2023).

5. For an excellent description of the origins of the International Atomic Energy Agency, see Bertrand Goldschmidt, “The Origins of the International Atomic Energy Agency,” IAEA Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 4 (August 1977).

6. 42 U.S.C. § 2013(e).

7. Ellen C. Collier, “United States Foreign Policy on Nuclear Energy,” Library of Congress Legislative Reference Service, May 6, 1968, p. LRS-7.

8. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957, Regulation of Armaments; Atomic Energy, Volume XX, ed. David S. Patterson (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1990), doc. 14 (NSC report no. 5507/2, dated March 12, 1955, on peaceful uses of atomic energy).

9. Maria Drogan, “The Atoms for Peace Program and the Third World,” Cahiers du monde russe, Vol. 60, Nos. 2-3 (2019): 441-460.

10. Nuclear Proliferation Factbook, S. Prt. 103-111, December 1994, pp. 48-62 (containing President Gerald Ford’s statement on nuclear policy, dated October 28, 1976).

11. Ibid., p. 54.

12. Sharon Squassoni, “Looking Back: The 1978 Nuclear Nonproliferation Act,” Arms Control Today, December 2008.

13. See Rashad Abuaish, “Saudi National Atomic Energy Project,” n.d., https://gnssn.iaea.org/NSNI/SMRP/Shared%20Documents/Workshop%2012-15%20December%202017/Saudi%20National%20Atomic%20Energy%20Project.pdf (presentation).

14. Simon Henderson and David Schenker, “Saudi Arabia’s Nuclear ‘Asks’: What Do They Want, What Might They Get?” PolicyWatch,

No. 3771 (August 15, 2023), https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/saudi-arabias-nuclear-asks-what-do-they-want-what-might-they-get.

15. Christopher M. Blanchard and Paul K. Kerr, “Prospects for U.S.-Saudi Nuclear Energy Cooperation,” CRS In Focus, IF10799, September 28, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10799.

16. Ibid.

17. International Atomic Energy Agency, “Communication Received From the Permanent Mission of Kazakhstan to the International Atomic Energy Agency Regarding Certain Member States’ Guidelines for the Export of Nuclear Material, Equipment and Technology,” INFCIRC/254/Rev14/Part 1, October 18, 2019 (containing “Guidelines for Nuclear Transfers”).

18. Office of Nuclear Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, “HALEU Demonstration Project

Starts Enrichment Operations in Ohio,”

October 11, 2023, https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/haleu-demonstration-project-starts-enrichment-operations-ohio.

19. Summer Said, “Saudi Arabia Eyes Chinese Bid for Nuclear Plant,” The Wall Street Journal, August 25, 2023.

Sharon Squassoni is a research professor at The George Washington University who previously held positions at the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, the State Department, and the Congressional Research Service.

“The Day After,” shown on the ABC television network, took viewers into the lives of characters in typical towns and cities in the midwestern United States, not far from U.S. nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos. Following a fictional NATO-Russia military confrontation that spun out of control, the film showed the shocking effects of an all-out nuclear exchange designed to hit “military and related-industrial targets” and the catastrophic aftermath.

“The Day After,” shown on the ABC television network, took viewers into the lives of characters in typical towns and cities in the midwestern United States, not far from U.S. nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos. Following a fictional NATO-Russia military confrontation that spun out of control, the film showed the shocking effects of an all-out nuclear exchange designed to hit “military and related-industrial targets” and the catastrophic aftermath.

For the Middle East, this could have had huge implications for peace, security, and cooperation akin to those of the 1978 Camp David Accords. The rumors began circulating in August that the United States was not just brokering the agreement but would provide security guarantees, access to military technology, and civilian nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia to sweeten the deal.

For the Middle East, this could have had huge implications for peace, security, and cooperation akin to those of the 1978 Camp David Accords. The rumors began circulating in August that the United States was not just brokering the agreement but would provide security guarantees, access to military technology, and civilian nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia to sweeten the deal.![Saudi Minister of Energy Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman al-Saud speaks at a conference in Riyadh in June, six months after he declared that the kingdom “wants the entire [nuclear] fuel cycle.” (Photo by Fayez Nureldine/AFP via Getty Images)](/sites/default/files/images/ACT_Photos/2023_12/2_ACT_Dec2023_Feature_Saudi_al-Saud.png) In January 2023, Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman told a local mining conference that Riyadh wants “the entire nuclear fuel cycle, which involves the production of yellowcake, low-enriched uranium, and the manufacturing of nuclear fuel both for our national use and of course for export.”

In January 2023, Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman told a local mining conference that Riyadh wants “the entire nuclear fuel cycle, which involves the production of yellowcake, low-enriched uranium, and the manufacturing of nuclear fuel both for our national use and of course for export.” Finally, URENCO Netherlands was the source of much technology for the Khan nuclear black market network. Although there have been many proposals, including from governmental experts and the IAEA, to multilateralize fuel cycle facilities with the objective of diminishing national control of sensitive fuel-cycle capabilities, these usually assume that the benefits will outweigh the risks. The historical evidence, however, is mixed.

Finally, URENCO Netherlands was the source of much technology for the Khan nuclear black market network. Although there have been many proposals, including from governmental experts and the IAEA, to multilateralize fuel cycle facilities with the objective of diminishing national control of sensitive fuel-cycle capabilities, these usually assume that the benefits will outweigh the risks. The historical evidence, however, is mixed. The last U.S. nuclear test explosion was conducted in September 1992, and since then, the United States has observed a test moratorium and supported the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Although the treaty has established a norm against nuclear explosive tests, it has not entered into force because eight specific states, including the United States, have not ratified it.

The last U.S. nuclear test explosion was conducted in September 1992, and since then, the United States has observed a test moratorium and supported the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Although the treaty has established a norm against nuclear explosive tests, it has not entered into force because eight specific states, including the United States, have not ratified it. The third thing is that the Nevada site people have done other national security missions not associated with the NNSA but associated with larger national security missions, in particular for the Department of Homeland Security. When the Department of Homeland Security’s Domestic Nuclear Detection Office was active, they wanted to test the monitors that they were putting at ports in the United States and around the world.

The third thing is that the Nevada site people have done other national security missions not associated with the NNSA but associated with larger national security missions, in particular for the Department of Homeland Security. When the Department of Homeland Security’s Domestic Nuclear Detection Office was active, they wanted to test the monitors that they were putting at ports in the United States and around the world. ACT: It’s been about a quarter century since the SSP was established and nuclear explosive testing in the United States was halted. Would you say, in your experience previously as a lab director and now as NNSA administrator, that the United States has a better or diminishing level of confidence in the reliability and performance of the warheads and the arsenal? Are we learning more from

ACT: It’s been about a quarter century since the SSP was established and nuclear explosive testing in the United States was halted. Would you say, in your experience previously as a lab director and now as NNSA administrator, that the United States has a better or diminishing level of confidence in the reliability and performance of the warheads and the arsenal? Are we learning more from With a potential change in government on the horizon, the United Kingdom has an opportunity to rethink its nuclear weapons policy and return to a leadership role on nuclear risk reduction and disarmament among the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). After decades of reductions, the Johnson government stunned the world in 2021 by raising the limit on the UK nuclear stockpile from 180 warheads to 260 warheads and by reducing arsenal transparency.

With a potential change in government on the horizon, the United Kingdom has an opportunity to rethink its nuclear weapons policy and return to a leadership role on nuclear risk reduction and disarmament among the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). After decades of reductions, the Johnson government stunned the world in 2021 by raising the limit on the UK nuclear stockpile from 180 warheads to 260 warheads and by reducing arsenal transparency. I and the Bomb: Nuclear Strategy and Risk in the Digital Age

I and the Bomb: Nuclear Strategy and Risk in the Digital Age Although the meeting in Washington produced no specific result and no specific date for follow-on talks was announced, U.S. officials said the discussion, which occurred amid rising nuclear and geopolitical tensions, was worthwhile simply because it took place.

Although the meeting in Washington produced no specific result and no specific date for follow-on talks was announced, U.S. officials said the discussion, which occurred amid rising nuclear and geopolitical tensions, was worthwhile simply because it took place. In a Nov. 14 statement, the states said that they “will be united upon any renewal of hostilities or armed attack on the Korean peninsula” that challenges UN principles and the security of South Korea.

In a Nov. 14 statement, the states said that they “will be united upon any renewal of hostilities or armed attack on the Korean peninsula” that challenges UN principles and the security of South Korea. “Today’s announcement is reflective of a changing security environment and growing threats from potential adversaries,” said John Plumb, assistant secretary of defense for space policy, in an Oct. 27 statement. “The United States has a responsibility to continue to assess and field the capabilities we need to credibly deter and, if necessary, respond to strategic attacks, and assure our allies.”

“Today’s announcement is reflective of a changing security environment and growing threats from potential adversaries,” said John Plumb, assistant secretary of defense for space policy, in an Oct. 27 statement. “The United States has a responsibility to continue to assess and field the capabilities we need to credibly deter and, if necessary, respond to strategic attacks, and assure our allies.” The measure was approved on Oct. 12 by an overwhelming 164-5 vote, suggesting that it will be adopted by the full assembly before it adjourns in December. Eight UN member states abstained.

The measure was approved on Oct. 12 by an overwhelming 164-5 vote, suggesting that it will be adopted by the full assembly before it adjourns in December. Eight UN member states abstained. The project has raised concerns among nuclear nonproliferation experts, who say it conflicts with long-standing U.S. nonproliferation efforts to minimize the civilian use of HEU, which can be converted more easily than low-enriched uranium (LEU) for use in nuclear weapons.

The project has raised concerns among nuclear nonproliferation experts, who say it conflicts with long-standing U.S. nonproliferation efforts to minimize the civilian use of HEU, which can be converted more easily than low-enriched uranium (LEU) for use in nuclear weapons.