January/February 2021

Since the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) entered into force on March 5, 1970, states-parties to the treaty have gathered every five years to assess implementation of and compliance with the treaty and to seek agreement on steps to advance common goals and objectives related to the three pillars of the treaty: nonproliferation, peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and disarmament.

This year, representatives from most of the 191 NPT members will meet no later than August for the 10th review conference, which has been delayed twice as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This year, representatives from most of the 191 NPT members will meet no later than August for the 10th review conference, which has been delayed twice as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With progress on key NPT goals stalled, relations between key nuclear-armed states poor, and some key nonproliferation successes in jeopardy, this review conference has the potential to be among the most contentious.

Argentinian Foreign Ministry official Gustavo Zlauvinen has been chosen to preside over the review conference as the president-designate. Among other diplomatic postings, Zlauvinen has served as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) representative to the United Nations in New York, where he represented the agency during NPT meetings from 2001 to 2009.

Zlauvinen spoke with Arms Control Today by video conference on December 9 from Buenos Aires. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Arms Control Today: This year [2020] marks the 50th anniversary of the entry into force of the NPT. From your perspective, as someone who has worked in the field for so many years at the international level, how has the treaty succeeded? How has it fallen short? Why is it important today?

Amb. Gustavo Zlauvinen: Yes, 2020 marks three anniversaries. First, it is the 50th anniversary of the NPT’s entry into force. The second is the 25th anniversary of the treaty’s indefinite extension in 1995. That was part of a grand bargain at that point, which is still valid and for many states is an important part of the bigger picture. Unfortunately, the third marking [of] 2020 is the 75th anniversary of the use of the atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

It is a very solemn and an important year, and it gives an opportunity and a challenge for states-parties, civil society, and the international community in general to ponder what the NPT has achieved in these 50 years and where it has fallen short of the aspirations that were the drivers during the treaty negotiations.

There are many accomplishments that the NPT and its states-parties have achieved. One in particular was to keep the number of nuclear-weapon states to a reduced number. It prevented many potential countries that could have had the capabilities, and maybe even the political will, to develop nuclear weapons from doing so. I’m not talking about cases like my own country, Argentina, or Brazil. Let’s start with Sweden. Remember that, in the 1960s, Sweden had a nuclear weapons program, and there is no secret about that. Other countries, very influential ones at that time, were concerned at the time that there was no norm against acquiring nuclear weapons.

To us now, it seems that’s the benefit of having the NPT. You know, it seems bizarre, even abnormal, to think that a country like Sweden could have had a nuclear weapons program. Not that it is impossible in today’s world, but that’s a sign of the NPT’s success. The NPT changed our mind-set in the sense that what was considered okay in the 1960s and part of the 1970s became unacceptable for most countries in the international community.

A second achievement is that while preventing the spread of countries with nuclear weapons, it helped the spread of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. You can see that in the large number of countries around the world that have adopted nuclear power generation and applications in nuclear medicines, agriculture, and many other sectors. This probably could not have happened without the NPT. In the 1960s, only a few countries had the technology, so it was not easy to get access to that technology by yourself. Therefore, you needed the cooperation from countries having nuclear technology, and those countries were not going to pass it on that easily. By accepting IAEA safeguards, as required by the NPT, countries received more chances of receiving nuclear technology transfers from more advanced nations, and that helped the transfer of technology.

A second achievement is that while preventing the spread of countries with nuclear weapons, it helped the spread of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. You can see that in the large number of countries around the world that have adopted nuclear power generation and applications in nuclear medicines, agriculture, and many other sectors. This probably could not have happened without the NPT. In the 1960s, only a few countries had the technology, so it was not easy to get access to that technology by yourself. Therefore, you needed the cooperation from countries having nuclear technology, and those countries were not going to pass it on that easily. By accepting IAEA safeguards, as required by the NPT, countries received more chances of receiving nuclear technology transfers from more advanced nations, and that helped the transfer of technology.

In both achievements, the key element is the robust IAEA safeguard system. What it has achieved is tremendous in that all non-nuclear-weapon countries under the NPT receive regular inspections from the IAEA to prove that their nuclear programs are not being diverted for the development and production of nuclear weapons.

Now, where does the NPT fall short? What I have heard during my consultations with states-parties is that a large majority of states-parties feel that progress toward the nuclear disarmament obligations of Article VI of the NPT, which is about achieving an eventual total elimination of weapons and total disarmament, has not evolved in the way that the NPT has provided for.

Another one is that some states-parties say that despite the treaty’s enablement of technology transfers, they are not receiving access to nuclear technologies from those countries having those technologies. They claim that they are blacklisted even though they are party to the NPT and have IAEA safeguards agreements, and they claim that this is for political reasons. This is a concern that has been expressed by not many, but at least some, states-parties.

There is also a discussion about making the IAEA safeguards system more robust and better able to show the nuclear intentions of NPT states-parties. After the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when Iraq was discovered with a clandestine nuclear weapons program just under the radar of the IAEA safeguards system, a review led to negotiations and the adoption of the Model Additional Protocol to nations’ safeguards agreements in 1995. At that time, IAEA member states decided that nations would adopt an additional protocol on a voluntary basis.

That is the dilemma that NPT communities still have. Several states-parties would like to have an additional protocol as the new verification standard for the NPT. But others, including Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, and a few others say that because it is not a mandatory measure, it therefore cannot be established as a new standard. So, that is an issue I expect to be debated at the review conference.

As to why the NPT remains important today, we should consider what would have happened if the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference had not extended the treaty indefinitely. Remember that Mexico and others at the 1995 conference were pushing for an extension of another 25 years in order to see whether the NPT nuclear-weapon states were going to fulfill their obligations under Article VI. They didn’t want to keep committing themselves as non-nuclear-weapon states forever while the nuclear-weapon states may not implement Article VI. So, what would the situation be today if the negotiations in 1995 had agreed to extend it only for 25 years? The treaty would have ended this year, and the review conference would not be a regular review conference; it would be a conference to extend the treaty. Under the present circumstances, it would have been extremely difficult to come to an agreement on the extension of the NPT.

So, it’s better to have the NPT with all its limitations rather than to not have the NPT. It is as relevant as 50 years ago because the nuclear genie is out of the bottle, obviously; and it will continue to be so for a while, unfortunately. As long as we have our situation, as long as we have nuclear weapons, as long as we have an incentive for some countries to develop a potential program for nuclear weapons, as long as you have the spread of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes but they are of a dual-use nature, then you will need to have a system under a treaty with legal obligations by which the large majority of the international community commits itself not to develop and not to use these awful, horrible weapons.

Maybe the states that are also party to the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will see that their approach is one to complement or fulfill that NPT aspiration to achieve full nuclear disarmament. That’s fine, but I think the TPNW would not have been possible without the NPT having been established in the first place.

ACT: The TPNW will enter into force on January 22, just about the time this interview will be published. If some nuclear-weapon states continue to oppose the treaty, could that provoke TPNW supporters and create schisms or rifts at the review conference? How will you seek to reconcile the views of states that believe the TPNW reinforces the NPT with those who say it creates a norm contrary to the NPT?

Zlauvinen: The TPNW is obviously a new fact that we have to take into account. Obviously for those states that are party to the TPNW and the NPT, they believe that the TPNW reinforces, complements, and completes the NPT. Meanwhile, other NPT states-parties that are not party to the TPNW have said that they will never join. They see that the new treaty has come to be a challenge and even to help erode the legal norms and systems that the NPT has established during these 50 years.

This is a debate that we must have and is already happening. Those who have not signed or ratified the TPNW cannot close their eyes and act as if the TPNW doesn’t exist. But I hope that this debate is not going to create another challenge, another problem at the review conference between NPT states-parties. We have to see how we maneuver that discussion. It will be up to the states that are party to both treaties to explain to those who are not party to the TPNW that the TPNW should not be seen as a challenge to the NPT. It is on them to explain and to prove that it is not contrary to the NPT, it has not come to erode the NPT. If they do their job correctly, hopefully they will convince at least the majority of those who have not signed and ratified the TPNW at least to accept that they have to live with that. At the end of the day, with this type of complex, difficult diplomatic negotiations, everything boils down to political will from both parties and the language. I always say that the language that we can develop to accommodate both positions will be key. I hope that, on both sides, they will be willing to make a political compromise so that we can move forward and this issue will not be a stumbling block for a successful outcome of the conference.

ACT: When you became president-designate of the review conference, you could not have foreseen the consequences of this COVID-19 pandemic. What have you been doing in these conditions to maintain the pace of preparation for the review conference? How are you seeking to engage states in the coming months and in the lead-up to the review conference and before the end of August?

Zlauvinen: The hiatus that we are facing due to the pandemic is something that we were not expecting when I officially took over as a president-designate in January 2020, just two months before the pandemic hit us in a major way. The main challenge was and still is how to keep momentum, how to help states-parties and civil society to keep momentum as we are unable to conduct negotiations until the review conference. That is obviously not going to happen because you cannot have negotiations before the review conference. Negotiations take place at the review conference.

Nevertheless, in every review cycle of the NPT, as has happened with many other treaties before their own review conferences, you have consultations and discussions among states-parties and members of the different regional groups. This is what I’ve been trying to do as president-designate: to keep motivating states-parties and delegations, to keep looking at the challenges that the NPT is facing, the problems that we are going to have at the review conference, not to shy away and to confront those issues without replacing negotiations. Let’s have open and frank discussions among the states-parties to the NPT and including civil society. The views from a gender perspective, the views from the industry, the views from youth—they are all part of our society. At the end of the day, we diplomats and government officials, we don’t work in a vacuum. We work in real life and on issues that affect real people. Therefore, the NPT should not be a closed club. It should be open to youth, industry, and gender perspectives if we want to keep the NPT fit for future generations.

In a normal situation, during the months before the review conference, the president-designate would travel to New York, Geneva, and Vienna for consultations with the regional groups in person. Then they will travel to several capitals to have bilateral conversations and discussions and to hear firsthand from the states-parties about their concerns, about their positions, and to see what margin of maneuver they will give the president-designate during the review conference.

In a normal situation, during the months before the review conference, the president-designate would travel to New York, Geneva, and Vienna for consultations with the regional groups in person. Then they will travel to several capitals to have bilateral conversations and discussions and to hear firsthand from the states-parties about their concerns, about their positions, and to see what margin of maneuver they will give the president-designate during the review conference.

I started traveling in January and February and the beginning of March, and then I had to stop. So obviously, that is a huge challenge because I have to start doing business in a different way that has not been done by my predecessors. I have to start engaging delegations and even capitals in a virtual manner, but it’s not the same as being in person. I have also held informal consultations with the regional groups, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the Western European and Others Group (WEOG), the Eastern European Group, and the Group of One (China). I have had do it virtually, which is not the same.

What I miss the most is that you can have the same conversations virtually as you can in person, but you cannot have the personal interactions in virtual discussions. Say that you go to Vienna, you meet with the WEOG or the NAM for two hours in a meeting room; and after that some delegation will approach, and you will have coffee with them; or another delegation will approach you in the corridor and tell you something that they could probably not tell you in front of others. In a more relaxed environment, maybe they can tell me things that they probably would not be able to in front of others, and I’m missing that part.

Even when I’m having virtual bilateral discussions, as several capitals asked me to do with senior officials of their own capitals, it’s kind of a scripted conversation because it’s being recorded. We have done a good deal of using these new technologies to reach out to the delegations and states-parties to continue the consultations. I’m trying to hold those every two months, so the next one will be in the beginning of February, then one in April, and then June or July before the conference.

I’m trying to challenge the delegations that when we do have those consultations, even virtually, to address the real important issues. So, let’s address substantive issues. Let us have a frank discussion, even if they disagree. Fine. I’m not afraid of delegations disagreeing. On the contrary, it is part of the nature of this political animal, the NPT. There are more than 190 parties. There will always be some disagreements, and you have to deal with that. The more those disagreements are being aired, there’s a better chance that we have that we can accommodate those positions at the review conference.

ACT: Based on what you know at this stage and based on the experience from the UN General Assembly and its First Committee meetings, how do you expect the review conference will physically operate? How many persons might be there? Might some sessions be held virtually?

Zlauvinen: Based on what we have seen of the General Assembly and the First Committee, the review conference will have a limited in-person presence. There could be one delegate per country at a given time at the conference room, plus two additional delegates linked virtually. It proved to work for the General Assembly, which managed to adopt resolutions, and for the First Committee also. But I understand that business was done in a reduced manner. They didn’t have time, for example, for formal presentations of draft resolutions. Some delegations were not pleased with the way that it worked under that hybrid concept.

Now, what may work for the General Assembly or the First Committee or the IAEA General Conference may not work for the NPT review conference. No two forums are going to have the same dynamics. We have to look into the NPT review process itself and see how the states-parties can engage with each other and try to get a successful outcome.

What I’ve heard so far from the consultation with all regional NPT groups is that a large majority of states-parties prefer to have a full-fledged review conference, meaning a conference that lasts four weeks, that will be in person, and that will allow for delegations from capitals to attend, as well as delegations from Geneva and Vienna.

The conference should allow for parallel meetings, in the sense that you may have two main committees working in parallel because the work is very extensive. We have many issues to handle, and even four weeks is not enough if you’re going to have, for example, one single conference room. That was the situation we would have faced had we decided to go ahead with the conference taking place in January 2021 in New York. The UN Secretariat advised us that, under those circumstances, under the pandemic circumstances, we would have had only one conference room for four weeks, and delegations found this unacceptable.

On the other hand, there is a group of states-parties that says the most important thing is to have the review conference as soon as possible, regardless of the format. That is another rift that I’m trying to avoid, so I have decided that we are going to have another round of consultations in April to discuss the time and the format of the review conference. I hope that, by April, the UN Secretariat can tell us, based on the overall pandemic situation in the world, how many conference rooms we may have in August, how many parallel meetings we can have, and if we will allow for in-person or limited in-person meetings. Based on this information, states-parties have to decide whether it will be acceptable to go ahead in August. If the UN Secretariat cannot provide us all the conference rooms and services necessary to have a full-fledged conference, then we are going to have another major, major headache in April on how we will proceed.

ACT: The NPT’s entry into force in 1970 helped open the way for U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control, but now that arms control architecture is under severe stress. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty is gone. The future of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) is uncertain. The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty has widespread support, but key nuclear-weapon states have still not ratified it. Many states have argued that the nuclear-weapon states are not meeting their NPT Article VI obligations and have failed to fulfill key obligations agreed at the 2010 review conference. How important is it to the health of the NPT and the success of the coming of this review that we see progress in these areas in the coming months?

Zlauvinen: The arms control treaties that the Soviet Union and the United States, and later Russia and the United States, have managed to agree to and implement during the last 40 years or so have eroded and deteriorated. The demise of the INF Treaty, the U.S. withdrawal from the Open Skies Treaty, and the questions about whether New START is going to be extended before it expires in February have contributed to a very pessimistic view by many that the chances for the 10th review conference to have a successful positive outcome are very slim. Obviously, the overall international security context has an impact on the NPT and its review conference. What is more important is the lack of agreement, but also of trust, between Russia and the United States and between China and the United States. This is not helping our conversations on how we move forward in the implementation of the review of the NPT in the next five years.

I’m not that pessimistic. I believe that the NPT has faced similar challenges in the past, that the arms control system put in place by the Soviet Union and the United States started in very difficult times and has evolved. Remember what President Ronald Reagan said: “Trust but verify.” You need some kind of verification, even if you’re going to try to trust your adversary.

The NPT has managed to overcome all those challenges in the past. I hope and I really believe that the NPT and its members are going to overcome the current challenges. We will also have to wait until January, when there is going to be a new administration in the United States. We have to see what the new administration is going to do regarding the extension of the New START. The current U.S. administration has placed a condition for extension, demanding that China also be included in the negotiations. China has openly rejected that proposal.

So, we have to see whether the new administration is going to continue with those new conditions or whether it’s going to extend New START for another year. We have to wait also to see if the new administration conducts a new nuclear posture review.

Nuclear disarmament, nuclear nonproliferation, nuclear technologies, and nuclear weapons are a matter of U.S. national security, and therefore they are one of the most important issues for any U.S. administration. Traditionally, change of administrations didn’t bring a major shift or changes in the overall U.S. approach to these issues. But in the past, we have seen some changes in the tone, in the attitude, the approaches from one administration to another. I hope that, by August, it will be an environment more conducive for our conference to achieve success.

What I mean by success is a meaningful and fruitful outcome, an outcome that is not going to be only a piece of paper, but an outcome that means practical things for the states-parties to implement in the next five years, an outcome that is going to be fruitful in the sense that everybody will leave the review conference saying that we have achieved something, maybe it’s not so much, but we have achieved something. We have a fruit. We have a result that we can take home and care for and implement.

The outcome will be up to the states-parties. If they want to have an overall document or if they want to have no document at all, fine. If they want to have a high-level political statement or declaration, fine. It’s up to them. I’m not going to be drafting such a declaration. It’s not in my prerogative to do so. It’s up to them.

ACT: This is the 50th anniversary of the entry into force of the treaty. This conference is seen by many as being unique and different because of that. How are you planning to elevate the profile or the stature of the meeting despite the pandemic conditions? Are you seeking some higher-level national participation in the conference by prime ministers and presidents, for instance, or in some other way trying to encourage a heads of state-level communique?

Zlauvinen: I hope that governments will see it is in their own interest to have an outcome that is going to be positive for them and therefore they’re going to do their utmost to help in the process. One way that they can do so is by attending at least the first few days of the conference at the highest levels. I cannot impose on parties who that high level should be, but heads of state or government would be more than welcome. Even if they are not able to attend at that level, I think foreign ministers will be very welcome. Before the 2020 review conference was delayed, we were expecting almost 40 foreign ministers and six or seven heads of state or government.

In my bilateral consultations, I’m encouraging states-parties to do so. But again, I cannot impose participation on heads of state or heads of government. That’s my wish. I hope so. I think it is going to be for their own benefit.

ACT: When you mentioned potential changes to U.S. nuclear policy by the next president, will you also look to see how policy might change toward the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)? Is it important that the United States return to the JCPOA and that Iran return to the limits of the deal?

Zlauvinen: The review conference will be addressing challenges to the safeguards system and obviously the Iran nuclear program. From what I have heard from delegations, that is going to be a very complex and difficult discussion. The JCPOA is going to be an issue of contention.

I’m not here to take sides. I’m not here to say whether the U.S. administration should go back to the JCPOA or whether Iran should limit itself. It’s up to the states-parties in the context of the NPT review conference. What I hope is that, by August next year, this issue will have evolved from where we stand today. I hope that the new administration will review its policy regarding the JCPOA, and whether the decision is to keep the current positions or change them back or move to a new position, I hope that, by August, it will have a positive result in the negotiations and discussions with Iran, and in particular at the IAEA regarding the Iran nuclear program. I hope that, by August, the whole situation regarding Iran’s nuclear program will be much clearer and less tense than it is now.

ACT: Even if tensions over the future of the JCPOA are resolved, there would still be discussion at this review conference about strengthening safeguards. Given the fact that some states have still not fully adopted an additional protocol to their IAEA safeguards agreements and some countries such as Saudi Arabia have outdated small-quantities protocol arrangements, how might the review conference encourage more states to adopt a stronger set of safeguards standards in the future?

Zlauvinen: This issue is also going to be an issue of contention because many countries believe that an additional protocol should be the new verification standard, while others don’t believe so. At least they believe that it is, and it is, on a voluntary basis. It’s not mandatory. This is linked to what many call the grand bargain, the 1995 decision of the review conference to extend the treaty indefinitely and the recommitment by all states to the nonproliferation obligations and to Article VI by the nuclear-weapon states.

Those countries that have not signed or ratified an additional protocol to their safeguards agreements have several reasons not to do so. I’m not here to support or take part in that. I’m just describing the situation the way that I see it. First, the IAEA Board of Governors, when it adopted the Model Additional Protocol in 1995, said that the decision for member states to adopt an additional protocol was voluntary. Therefore, those countries that have not adopted it have decided for national reasons not to.

Secondly, some countries believe that they have adequate systems in place. Argentina and Brazil, for example, believe that their current safeguard system, consisting of a bilateral agreement, an agreement with the Brazilian-Argentinian Agency for the Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC), and a safeguards agreement with the IAEA, is strong enough and it doesn’t leave any doubts about the peaceful nature of both nuclear programs. Therefore, they don’t need to have an additional protocol because they have almost that kind of additional protocol in the ABACC itself.

Beyond those technicalities, there is the issue that countries that have placed their peaceful nuclear programs under safeguards agreements believe that they have fulfilled their obligations under Articles I and III. Now, they don’t want to take on more nonproliferation obligations while nuclear-weapon states have not fulfilled their own obligations under Article VI. This is becoming more of a political question as opposed to a technical issue, so that makes the overall issue a bit more complicated. This going to be a contentious issue at the review conference.

I don’t believe there is going to be an agreement. It is not up to the NPT review conference to suggest that an additional protocol is mandatory. It is up to the IAEA Board of Governors. Nevertheless, there are going to be many voices at the review conference calling for an additional protocol to be the new standard, so we will see how we manage that disagreement.

ACT: How can you move forward the debate on the zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East? This has been a goal that states-parties committed to try to advance, beginning with the outcome of the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference. What are the main issues that still need to be settled, and who needs to be involved in sorting them out?

Zlauvinen: It’s going to be another challenge, another issue of contention as it has been for many review conferences. I thought that the 1995 decision, a resolution to push for the establishment of a nuclear weapon-free zone and other weapons of mass destruction-free zone in the Middle East, was going to do the trick, but it didn’t. At the end of the day, it depends on overall political settlement among all the states in the region. For that, obviously you need Israel. You cannot establish a nuclear weapon-free zone in the Middle East without the direct involvement of Israel, and so far, Israel has not participated.

There is a new development with regard to this issue that is going to be important at the negotiations and discussions during the NPT review conference, and that is the UN-convened conference in November 2019 on the establishment of such a zone in the Middle East. Most countries in the Middle Eastern region, as well as many European nations and others, attended that conference, with the exception of Israel. The United States also did not participate. The result of that conference is being seen by many parties to the NPT as a step forward in the direction that was designed by the 1995 decision on the Middle East. Therefore, they see that finally there is positive movement, a positive development in the implementation of the 1995 resolution. Therefore, they would like this to be reflected in the outcome of the NPT review conference.

Other countries, Iran and Syria in particular, believe that while the UN-convened conference is important, it is a separate track from NPT Middle East resolutions. They say that there are two different tracks, you cannot link them, so we should not even mention the UN-convened conference at the review conference.

Then you have a separate view, held particularly by the United States, that it refuses to accept that the UN-convened conference even took place or existed or mattered at all. Therefore, it doesn’t want to have any mention at the NPT review conference of that UN conference. Therefore, something that could be seen as a positive step could also be another complication for our conversations and discussions at the NPT review conference. I hope that we can manage language that will accommodate the different positions to acknowledge the UN-convened conference and maybe just set the tone for how to keep moving from the NPT point of view during the next five years in pursuit of the goal of the establishment of such a zone in the Middle East.

It is very important for the countries in the Middle East. I’ve been told by all states-parties that come from that region during my consultations that, for them, this is one of the most important issues for the review conference and, without an adequate reflection of this issue at the review conference, the review conference is going to have a big challenge. Aside from nuclear disarmament, this is the second most important challenge we face at the review conference.

ACT: A few times, you’ve mentioned the position of the current administration coming in late January. With the new administration on the way, given what you know about the tendencies of U.S. President-elect Joe Biden, are you more hopeful that his administration will be able to bridge that divide about simply recognizing past review conference commitments; and can that help move this conference toward a meaningful, fruitful outcome?

Zlauvinen: Indeed, the issue of how we deal with the commitments made in past NPT review conferences is going to be another crucial element. It’s part of the challenge that we are going to face related to nuclear disarmament, because when people talk about past commitments, they mainly focus on the commitments of past conferences related to progress toward the implementation of Article VI. Yes, the current U.S. administration has expressed that it saw no need to reconfirm those commitments because circumstances have changed. It claimed that those commitments were made in the past during a different global security environment and different situations and those situations don’t exist anymore. There is a lack of confidence and trust, among nuclear-weapon states in particular, and therefore they are not in a position to reconfirm those commitments. Obviously, for a great majority of states-parties, that’s very important. That is key because they believe that the commitments made at previous conferences are an integral part of the obligations under the NPT. This is the view that they have, and therefore they would like to have those commitments reasserted during the next review conference.

I cannot speak just now on what the new administration is going to do or what approach it is going to have regarding those commitments. Whichever that position may be, I hope that, at the review conference, we can find a way among all the states-parties to a common position on this. But more important than those commitments is what we are going to do as a community regarding nuclear weapons, what we’re going to do regarding the full implementation of Article VI. I believe that the reason why many states signed and ratified the TPNW is because of their frustrations on the lack of progress on the implementation of nuclear disarmament. This is being seen by many, not only in government but in civil society, that as a global community we have to do something better regarding moving forward to that overall goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.

I would like to have that question answered by the new administration. I think that the commitments are a secondary or tertiary issue related to that. If the new administration answers that question, then it will be easy to know what they’re going to do with the commitments at previous conferences. It is more important to answer how they’re going to deal with the demand from the overall community that nuclear-weapon states have an obligation, they have a responsibility to do something much more regarding how we move forward to that goal of achieving one day a world free of nuclear weapons.

President Donald Trump did not. He and his team failed to resolve a dispute over Russian noncompliance with the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and bungled talks to extend the last remaining U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control agreement, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is due to expire Feb. 5.

President Donald Trump did not. He and his team failed to resolve a dispute over Russian noncompliance with the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and bungled talks to extend the last remaining U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control agreement, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is due to expire Feb. 5.

For example, in 1979, during the height of the Cold War, then-Sen. Biden spoke at the Arms Control Association Annual Dinner about “The Necessity of Nuclear Arms Control,” noting that “pursuing arms control is not a luxury or a sign of weakness, but an international responsibility and a national necessity.”

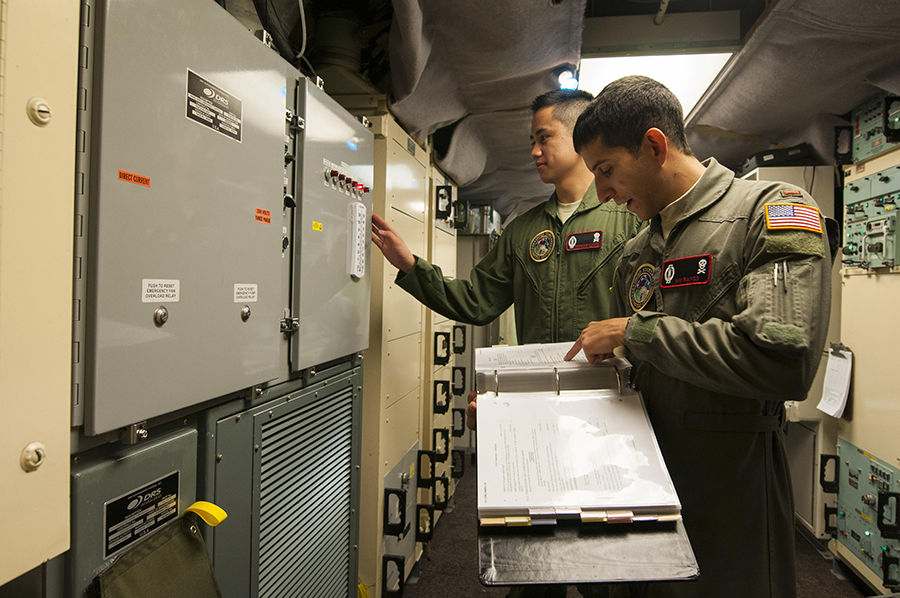

For example, in 1979, during the height of the Cold War, then-Sen. Biden spoke at the Arms Control Association Annual Dinner about “The Necessity of Nuclear Arms Control,” noting that “pursuing arms control is not a luxury or a sign of weakness, but an international responsibility and a national necessity.” New START extension. When the Biden administration begins on January 20, its first arms control task will be to extend New START, which expires on February 5. It should agree to the Russian proposal to extend the treaty for five years. That would constrain Russian strategic forces to 2026 and continue the flow of information about those forces provided by the treaty’s verification provisions, while requiring no changes in U.S. strategic modernization plans.

New START extension. When the Biden administration begins on January 20, its first arms control task will be to extend New START, which expires on February 5. It should agree to the Russian proposal to extend the treaty for five years. That would constrain Russian strategic forces to 2026 and continue the flow of information about those forces provided by the treaty’s verification provisions, while requiring no changes in U.S. strategic modernization plans. Although the Trump administration has exacerbated every nuclear challenge facing the United States by increasing nuclear tensions and the risk of use, upending key arms control agreements, and increasing the salience of nuclear weapons in national security, some of the challenges and underlying issues predate President Donald Trump. Entrenched views and misguided thoughts of controlling escalation have underscored a dangerous return of the belief that the United States can fight and “win” a nuclear war. Under Trump,

Although the Trump administration has exacerbated every nuclear challenge facing the United States by increasing nuclear tensions and the risk of use, upending key arms control agreements, and increasing the salience of nuclear weapons in national security, some of the challenges and underlying issues predate President Donald Trump. Entrenched views and misguided thoughts of controlling escalation have underscored a dangerous return of the belief that the United States can fight and “win” a nuclear war. Under Trump, The Trump administration reoriented the U.S. approach to arms sales by prioritizing perceived economic gains over foreign policy concerns and national security interests. Indeed, the administration made selling weapons a central pillar of U.S. foreign policy priorities. During the first three years of President Donald Trump’s tenure, U.S. foreign military sales agreements totaled more than $200 billion. Yet, in using arms sales as a political tool for short-sighted and mostly economic objectives, the administration’s arms transfer policies often overlooked risks to human rights, civilian protection, stability, and longer-term U.S. strategic interests. Although the value of weapons sold is telling, what is more concerning is the recipients of these weapons, with the United States actively pushing through arms sales to countries with concerning human rights records, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the Philippines.

The Trump administration reoriented the U.S. approach to arms sales by prioritizing perceived economic gains over foreign policy concerns and national security interests. Indeed, the administration made selling weapons a central pillar of U.S. foreign policy priorities. During the first three years of President Donald Trump’s tenure, U.S. foreign military sales agreements totaled more than $200 billion. Yet, in using arms sales as a political tool for short-sighted and mostly economic objectives, the administration’s arms transfer policies often overlooked risks to human rights, civilian protection, stability, and longer-term U.S. strategic interests. Although the value of weapons sold is telling, what is more concerning is the recipients of these weapons, with the United States actively pushing through arms sales to countries with concerning human rights records, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the Philippines. This fact, as well as the increasing availability of advanced biotechnologies, contributes to a growing threat. Furthermore, the taboo against developing and using banned biological weapons is eroding. In recent years, Syria, Russia, and North Korea have employed prohibited chemical weapons in brazen attacks in Syria, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, and last summer against Russian dissident Alexei Navalny in Siberia. Although these were not biological attacks, a country that develops and uses horrific chemical weapons seems unlikely to respect the parallel taboo against bioweapons. We need to strengthen the Chemical Weapons and Biological Weapons Conventions and make pariah countries that wantonly violate them pay a heavy price.

This fact, as well as the increasing availability of advanced biotechnologies, contributes to a growing threat. Furthermore, the taboo against developing and using banned biological weapons is eroding. In recent years, Syria, Russia, and North Korea have employed prohibited chemical weapons in brazen attacks in Syria, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, and last summer against Russian dissident Alexei Navalny in Siberia. Although these were not biological attacks, a country that develops and uses horrific chemical weapons seems unlikely to respect the parallel taboo against bioweapons. We need to strengthen the Chemical Weapons and Biological Weapons Conventions and make pariah countries that wantonly violate them pay a heavy price. Domestically, Biden must make crystal clear that preventing biological threats is a core mission of U.S. defense and national security agencies, in addition to the traditional health agencies. As Obama did during the Ebola crisis, the president should chair regular meetings of the National Security Council with the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to expand U.S. efforts and monitor progress.

Domestically, Biden must make crystal clear that preventing biological threats is a core mission of U.S. defense and national security agencies, in addition to the traditional health agencies. As Obama did during the Ebola crisis, the president should chair regular meetings of the National Security Council with the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to expand U.S. efforts and monitor progress. Biden expressed his intention to return the United States to compliance with the 2015 deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), if Iran does likewise. In a September opinion piece for CNN, Biden wrote that “[i]f Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

Biden expressed his intention to return the United States to compliance with the 2015 deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), if Iran does likewise. In a September opinion piece for CNN, Biden wrote that “[i]f Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.” A variety of factors unique to each period of diplomacy have hampered negotiations and resulted in short-lived agreements, but North Korea has yet to denuclearize quite simply because its leadership remains convinced that nuclear weapons are the surest form of regime security. As years of diplomacy, sanctions, and even serious considerations of employing military force have demonstrated, there is no silver bullet for the North Korean nuclear challenge. The best options are persistent, sustained diplomacy to build trust and collectively chart a phased road map to denuclearization, paired with the maintenance of robust deterrence capabilities through close coordination between the United States and its allies until the day Pyongyang no longer poses a threat.

A variety of factors unique to each period of diplomacy have hampered negotiations and resulted in short-lived agreements, but North Korea has yet to denuclearize quite simply because its leadership remains convinced that nuclear weapons are the surest form of regime security. As years of diplomacy, sanctions, and even serious considerations of employing military force have demonstrated, there is no silver bullet for the North Korean nuclear challenge. The best options are persistent, sustained diplomacy to build trust and collectively chart a phased road map to denuclearization, paired with the maintenance of robust deterrence capabilities through close coordination between the United States and its allies until the day Pyongyang no longer poses a threat. For these reasons, advancing denuclearization and peace diplomacy with North Korea should be considered among the top priorities of the incoming Biden administration, notwithstanding the long list of other pressing domestic and foreign policy challenges that will need to be addressed from day one. President Joe Biden has committed to engage in “principled diplomacy” to work toward a denuclearized North Korea and a permanent peace on the Korean peninsula. He has stressed a desire to work closely with allies and partners to accomplish these goals. To operationalize these commitments and insert constructive momentum into the long-stalled diplomatic process with North Korea, the Biden administration should rapidly empower a U.S negotiating team and signal to Pyongyang to return to the negotiating table to build on the principles Washington and Pyongyang agreed to at the Singapore summit, including working toward a new U.S.-North Korean relationship and the complete denuclearization and establishment of peace on the Korean peninsula.

For these reasons, advancing denuclearization and peace diplomacy with North Korea should be considered among the top priorities of the incoming Biden administration, notwithstanding the long list of other pressing domestic and foreign policy challenges that will need to be addressed from day one. President Joe Biden has committed to engage in “principled diplomacy” to work toward a denuclearized North Korea and a permanent peace on the Korean peninsula. He has stressed a desire to work closely with allies and partners to accomplish these goals. To operationalize these commitments and insert constructive momentum into the long-stalled diplomatic process with North Korea, the Biden administration should rapidly empower a U.S negotiating team and signal to Pyongyang to return to the negotiating table to build on the principles Washington and Pyongyang agreed to at the Singapore summit, including working toward a new U.S.-North Korean relationship and the complete denuclearization and establishment of peace on the Korean peninsula. Following the 2017 presidential inauguration, the Trump administration had to address immediately the use of chemical weapons by state actors when Kim Jong Nam, the half brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, was assassinated with VX nerve agent in Malaysia. The United States blamed and sanctioned North Korea, which is not party to the CWC, for this fatal chemical attack.

Following the 2017 presidential inauguration, the Trump administration had to address immediately the use of chemical weapons by state actors when Kim Jong Nam, the half brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, was assassinated with VX nerve agent in Malaysia. The United States blamed and sanctioned North Korea, which is not party to the CWC, for this fatal chemical attack. he United States also should provide foreign assistance to CWC states-parties in good standing with international norms to develop their national laws to penalize the use of chemical weapons. Despite the requirement in the CWC for the 193 member states to have national implementing laws, currently 39 states-parties only have accomplished this partially, and 35 states-parties are not satisfying this requirement at all. In 2018, the United States joined about 30 countries and international organizations for the launch of the International Partnership Against Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons, a promising French initiative to identify and penalize perpetrators and build legal capacities. The goal of the Biden administration should be to mitigate legal safe havens for users of chemical weapons around the world and to develop capacities via bilateral and multilateral engagements, such as this international partnership, so that each partner country has the capabilities to prosecute those that should never have broken CWC norms.

he United States also should provide foreign assistance to CWC states-parties in good standing with international norms to develop their national laws to penalize the use of chemical weapons. Despite the requirement in the CWC for the 193 member states to have national implementing laws, currently 39 states-parties only have accomplished this partially, and 35 states-parties are not satisfying this requirement at all. In 2018, the United States joined about 30 countries and international organizations for the launch of the International Partnership Against Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons, a promising French initiative to identify and penalize perpetrators and build legal capacities. The goal of the Biden administration should be to mitigate legal safe havens for users of chemical weapons around the world and to develop capacities via bilateral and multilateral engagements, such as this international partnership, so that each partner country has the capabilities to prosecute those that should never have broken CWC norms. This year, representatives from most of the 191 NPT members will meet no later than August for the 10th review conference, which has been delayed twice as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This year, representatives from most of the 191 NPT members will meet no later than August for the 10th review conference, which has been delayed twice as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. A second achievement is that while preventing the spread of countries with nuclear weapons, it helped the spread of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. You can see that in the large number of countries around the world that have adopted nuclear power generation and applications in nuclear medicines, agriculture, and many other sectors. This probably could not have happened without the NPT. In the 1960s, only a few countries had the technology, so it was not easy to get access to that technology by yourself. Therefore, you needed the cooperation from countries having nuclear technology, and those countries were not going to pass it on that easily. By accepting IAEA safeguards, as required by the NPT, countries received more chances of receiving nuclear technology transfers from more advanced nations, and that helped the transfer of technology.

A second achievement is that while preventing the spread of countries with nuclear weapons, it helped the spread of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. You can see that in the large number of countries around the world that have adopted nuclear power generation and applications in nuclear medicines, agriculture, and many other sectors. This probably could not have happened without the NPT. In the 1960s, only a few countries had the technology, so it was not easy to get access to that technology by yourself. Therefore, you needed the cooperation from countries having nuclear technology, and those countries were not going to pass it on that easily. By accepting IAEA safeguards, as required by the NPT, countries received more chances of receiving nuclear technology transfers from more advanced nations, and that helped the transfer of technology.

In a normal situation, during the months before the review conference, the president-designate would travel to New York, Geneva, and Vienna for consultations with the regional groups in person. Then they will travel to several capitals to have bilateral conversations and discussions and to hear firsthand from the states-parties about their concerns, about their positions, and to see what margin of maneuver they will give the president-designate during the review conference.

In a normal situation, during the months before the review conference, the president-designate would travel to New York, Geneva, and Vienna for consultations with the regional groups in person. Then they will travel to several capitals to have bilateral conversations and discussions and to hear firsthand from the states-parties about their concerns, about their positions, and to see what margin of maneuver they will give the president-designate during the review conference.