January/February 2024

By Ekaterina Lapanovich, Laura Lepsy, and Alain Ponce Blancas

On a summer morning in 1953, soldiers evacuated all but a few farmers from a village in the Kazakh steppe without explaining the move.

After the group departed, the farmers left behind were surprised by a huge explosion and went outside to observe the spectacle better. Later, the soldiers returned, wearing protective suits, to conduct measurements on the witnesses.

This is the way a survivor described in the book Atomic Steppe how the inhabitants of Karaul, located around 95 kilometers from the former Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan, experienced the day of the first Soviet thermonuclear test.1 The volume is a testament to the fact that the global history of atomic testing is one of ignorance and deception, with innocent civilians deprived of full knowledge about the dangerous aftereffects of the nuclear testing that they unwittingly experienced.

This is the way a survivor described in the book Atomic Steppe how the inhabitants of Karaul, located around 95 kilometers from the former Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan, experienced the day of the first Soviet thermonuclear test.1 The volume is a testament to the fact that the global history of atomic testing is one of ignorance and deception, with innocent civilians deprived of full knowledge about the dangerous aftereffects of the nuclear testing that they unwittingly experienced.

In Kazakhstan, around seven years into nuclear testing, Soviet authorities kept secret information on the health effects of consuming contaminated food and water rather than share it with civilian health institutions that could have used the data to help affected individuals.2 Similarly, populations exposed to U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands were not given access to their own medical records for many years.3

From the farmers in Kazakhstan to indigenous communities in Nevada to the islanders of the Indo-Pacific region, millions of people were harmed, and countless acres were contaminated by fallout from more than 2,000 nuclear tests conducted by the Soviet Union, the United States, and other nuclear-weapon states since 1945. It is a dark legacy of injustice for which the nuclear-weapon states still have not fully atoned.

The Imperative of Justice

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which entered into force in 2021, has made achieving epistemic justice for nuclear testing-affected populations—the remedying of unfair treatment in knowledge-related practices, such as deprivation of access to historical and scientific data—one of its major tenets. The second meeting of TPNW states-parties, held in November in New York, laid the groundwork for taking action.

Regardless of what TPNW states-parties do, however, the effect will remain limited because no nuclear-weapon state will join the treaty soon or engage in related deliberations. To address this problem, the epistemic justice issue should be moved to a broader arena. An expert-level global conference on the legacy of nuclear testing would be a good start.

The TPNW evolved from a series of conferences that dealt with the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, in Oslo in 2013; Nayarit, Mexico, in 2014; and Vienna in 2014.4 The first meeting of states-parties, in 2022 in Vienna, established a working group, co-chaired by Kazakhstan and Kiribati, on victim assistance, environmental remediation, international cooperation and assistance, which presented its recommendations to the second TPNW meeting.

The working group focused on measures to fulfill the “positive obligations” that are anchored in the treaty’s Article 6, on victim assistance and environmental remediation, and Article 7, on international assistance and cooperation. Those measures included the establishment of a voluntary reporting process by which states-parties would share relevant information with each other and the wider public. This reporting process seeks to regularize the exchange of valuable information required to assist victims and remediate the environment. It could also facilitate broader international cooperation and assistance by allowing potential donor states to identify the needs of affected states-parties.5

The format encourages states-parties to provide specific data based on the same criteria so that the data can be processed and analyzed systematically. Reporting questions also address epistemic standards related to measuring the effects of nuclear tests, such as the methodology of assessment and criteria used to define victimhood. The format therefore confronts two major barriers to effective victim assistance and environmental remediation: the scarcity of systematic data and the absence of universal standards for defining victimhood.

The format encourages states-parties to provide specific data based on the same criteria so that the data can be processed and analyzed systematically. Reporting questions also address epistemic standards related to measuring the effects of nuclear tests, such as the methodology of assessment and criteria used to define victimhood. The format therefore confronts two major barriers to effective victim assistance and environmental remediation: the scarcity of systematic data and the absence of universal standards for defining victimhood.

Although this reporting format may ameliorate past harms, the structural reasons for epistemic injustice can be remedied in most cases only by the states that conducted the tests. For instance, affected states and communities often are unable to access the testing records that may help them identify and develop appropriate policy measures for mitigating the consequences of nuclear testing because such records may be classified, privileged, or simply not readily accessible.6 Only states with nuclear weapons could decide to share this information, but none of them will become parties to the TPNW in the near future and provide a report according to the new standard format.

Kazakhstan and Kiribati are aware of this problem. In their report as working group co-chairs, they noted that one of the major problems in assessing the impact of nuclear testing is the lack of access to relevant information that “may not be held by affected states-parties.” They included a section in the new reporting format that asks states-parties to report about “efforts to engage and exchange information with states not party that have used or tested nuclear weapons regarding their assistance to affected parties.”

The co-chairs took the extra step of putting the legacy of nuclear testing on the agenda of multilateral forums where nuclear-weapon states participate. The revised final draft document of the 2022 review conference of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) contained an appeal to “all governments…with expertise in the field of clean-up and disposal of radioactive contaminants, to consider giving appropriate assistance…in affected areas,”7 thereby effectively bringing TPNW Article 7 into the NPT orbit. In a working paper for the 2023 preparatory committee for the next NPT review conference, scheduled for 2026, Kazakhstan and Kiribati argue that nuclear-weapon states should engage in scientific and technical “information exchanges with [NPT] states-parties whose territories served as test sites [including on] the potential effects of nuclear contamination and types of responses.”8

Most recently, last October, the co-chairs co-sponsored the UN General Assembly resolution on the legacy of nuclear weapons,9 which asked the secretary-general to report on the views and proposals of states regarding efforts and ongoing needs related to victim assistance and environmental remediation, the same questions that the TPNW reporting format aims to answer. Many states-parties at the TPNW meeting in November referred to the October resolution as a mechanism for “universalizing” the TPNW’s assistance and cooperation requirements.

Although 171 states voted in favor of the resolution, all nine states that possess nuclear weapons abstained or voted against it. This result clarifies two major points. On one hand, the agenda of positive obligations in dealing with the nuclear testing legacy enjoys wide support, including from NATO states such as Germany10 and Norway,11 who are not TPNW state-parties but attended the TPNW meeting as observer states and emphasized their interest in working on the humanitarian perspective on the legacy of testing. On the other hand, the fact that all nuclear-weapon states voted against or abstained from the vote on the resolution reflects their reluctance to engage in multilateral forums that address the consequences of nuclear testing. It does not mean, however, that nuclear-weapon states have not taken national action to deal with the consequences of nuclear testing.

The Remediation Record

Most nuclear-weapon states have some form of commemoration or compensation instrument for victims of nuclear testing, even though their depth and scope vary widely from covering only veterans, as China and the United Kingdom do, to also covering civilians as France, Russia, and the United States do, to covering foreign territory, as in the U.S. agreement with the Marshall Islands. Eligibility for compensation may be determined by a number of factors, including an estimated minimum radiation dose to which an individual was exposed as a result of testing, as is the case of China, France, Russia, the UK, and the United States.

Establishing accurate estimates of radiation doses is generally difficult due to a scarcity of data, given the insufficient number of monitoring stations in operation at the time of testing.12 Yet, declassifying whatever data exist to process it in model-based analysis may improve the estimates of received dosage. A case in point is a 2022 study using recently declassified documents and atmospheric transport modeling of radioactive fallout to determine that certain local populations received considerably higher effective doses than had been concluded by the French Energy Commission in 2006.13

The willingness of nuclear-weapon states to declassify testing data varies. China has not declassified any data.14 The UK in 2018 even limited access to nuclear testing-related files that had previously been public and are now being reviewed anew for declassification.15 Although Russia declassified many documents on the history of the Soviet nuclear testing program,16 the picture is still fragmented and incomplete. In some cases, when Kazakh officials requested access to relevant Soviet data, they hit a wall of silence in Moscow.17

Recently, there has been some progress in France and the United States, where large-scale data declassification occurred. France in 2021 established a governmental commission to declassify documents relating to testing in French Polynesia.18 The United States declassified 14,000 records on testing in the Marshall Islands and made them publicly available.19 That said, there is considerable room for improvement. In both cases, civil society and expert communities have criticized declassification policies as “chaotic and disjointed.”20 The data made available are often scattered over different archives and, for logistical reasons, cannot be accessed by affected communities.21 In its 2022 feasibility study on declassifying the Marshall Islands testing data, the Public Interest Declassification Board, which was established by the U.S. Congress, emphasized the need not only to declassify data, but also to process and make accessible previously declassified or even unclassified data by means of strategic digitization and application of artificial intelligence technology to identify the relevant records.22

A Modest Proposal

Switzerland, an observer state for the TPNW meeting, has encouraged the states-parties to frame the issues of victim assistance and environmental remediation in such a way that broad support for the treaty, including among nuclear-weapon states, becomes more possible.23 The fact that France, Russia, and the United States have a considerable record of data declassification shows that, in principle, they might be amenable to engage on the matter. Yet, their votes against the UN resolution on the legacy of nuclear weapons may reflect a reluctance to incur some form of universal accountability.

If TPNW states want nuclear-weapon states to support the victim assistance and environmental remediation agenda, the TPNW framework or even the NPT might not be viable for the time being. Instead, an international conference on the legacy of nuclear testing with a technical expert-level focus might be a better mechanism to strike the balance between securing the nuclear-weapon states’ commitment and yielding benefits for testing-affected states.24

If TPNW states want nuclear-weapon states to support the victim assistance and environmental remediation agenda, the TPNW framework or even the NPT might not be viable for the time being. Instead, an international conference on the legacy of nuclear testing with a technical expert-level focus might be a better mechanism to strike the balance between securing the nuclear-weapon states’ commitment and yielding benefits for testing-affected states.24

To initiate such a proposal, one pathway could be adoption of a UN resolution on convening a conference for sharing knowledge about the consequences of nuclear testing. To win support from nuclear-weapon states, this resolution should not include naming-and-shaming aspects. It could be co-sponsored by potential bridge-builders in the areas of victim assistance and environmental remediation, such as Germany, Norway, and Switzerland, as well as allies of nuclear-weapon states that suffered from testing, such as Australia and Kazakhstan.

The conference should enable experts to provide affected states with a better picture of which data and data processing methodology are needed to improve their national remediation programs. That could be done by sharing best practices and modeling techniques of the nuclear-weapon states on addressing a lack of data and on archival research on harvesting existing data. It could serve as an initial brokering point for launching formal and informal partnerships among technical experts, including those from nuclear-weapon states and from states that were affected by testing.

Nuclear-weapon states also could be encouraged to make widely available or share bilaterally with affected states such data as nuclear test site locations, test dates, and isotope composition, including formerly classified data.25 By developing synergies, the conference could be a starting point for a global data-based effort to deal with the humanitarian and environmental legacies of nuclear testing.

Almost 75 years after the first nuclear test in Kazakhstan, villagers around the former Semipalatinsk test site are still physically and economically endangered by how little they know about the contamination of their lands. Because toxic acreage is not demarcated from uncontaminated land, the villagers may face health risks by unknowingly accessing contaminated land or may leave safe farming land idle out of fear of contamination.26

To address this challenge, the Kazakh government plans to establish the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Safety Zone, which will demarcate officially and enclose the contaminated land.27 Improved technical and expert cooperation brokered through a conference on the legacy of nuclear testing could help Kazakhstan gain the support required for the effective implementation of its rehabilitation and remediation efforts in the Semipalatinsk region. This would be a step forward in the struggle for long-overdue epistemic justice for victims of nuclear testing and offer a constructive example of the solutions available to other affected countries and populations to atone for this deadly inheritance.

ENDNOTES

1. Togzhan Kassenova, Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022), p. 38.

2. Ibid., pp. 54, 59.

3. See Declassification of Records Relating to Nuclear Weapons Testing and Cleanup Activities in the Marshall Islands: Feasibility Study,

August 2022, p. 18, https://www.archives.gov/files/pidb/recommendations/marshall-islands-feasibility-study-2022-.pdf.

4. For detailed information about the three conferences, see Reaching Critical Will, “Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons,” n.d., https://reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/hinw (accessed January 3, 2024).

5. International Human Rights Clinic, Harvard Law School, “Reporting Guidelines for Articles 6 and 7 of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons: Precedent and Recommendations,” May 2023, https://humanrightsclinic.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/TPNW-reporting-report-5-15-23-FINAL.pdf.

6. See Nuclear Truth Project, “Challenging Nuclear Secrecy: A Discussion of Ethics, Hierarchies and Barriers to Access in Nuclear Archives,” July 2023, https://nucleartruthproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Challenging-Nuclear-Secrecy-report-NTP-31-July-2023-low-res.pdf.

7. 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Final Document,” NPT/CONF.2020/CRP.1/Rev.2, August 25, 2022, para. 93.

8. See Preparatory Committee for the 2026 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Addressing the Past Use and Testing of Nuclear Weapons: Working Paper Submitted by Kazakhstan and Kiribati,” NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.27, July 28, 2023.

9. UN General Assembly, “Addressing the Legacy of Nuclear Weapons: Providing Victim Assistance and Environmental Remediation to Member States Affected by the Use or Testing of Nuclear Weapons,” A/C.1/78/L.52, October 12, 2023.

10. Susanne Riegraf, Statement of Germany to the second meeting of states-parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), n.d., pp. 3-4, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/2msp/statements/29Nov_Germany.pdf (meeting held November 27-December 1, 2023).

11. Tor Henrik Andersen, Statement of Norway to the second meeting of TPNW states-parties, n.d., p. 3, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/2msp/statements/29Nov_Norway.pdf (meeting held November 27-December 1, 2023).

12. Committee to Assess the Scientific Information for the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program, “Assessment of the Scientific Information for the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program,” National Research Council, 2005, p. 5, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11279/chapter/1; INTERPRT, Disclose, and Science and Global Security Program, Princeton University, “The Compensation Trap,” n.d., https://moruroa-files.org/en/investigation/battle-for-compensation (accessed December 3, 2023).

13. Sébastien Philippe, Sonya Schoenberger, and Nabil Ahmed, “Radiation Exposures and Compensation of Victims of French Atmospheric Nuclear Tests in Polynesia,” Science & Global Security, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2022): 62-94.

14. Peter Suciu, “China’s Nuclear Tests Might Have Killed Hundreds of Thousands,” The National Interest, April 30, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/china’s-nuclear-tests-might-have-killed-hundreds-thousands-184134.

15. Nuclear Truth Project, “Challenging Nuclear Secrecy,” p. 9.

16. See “Атомный проект СССР: документы и материалы” [USSR atomic project: Documents and materials], History of Rosatom, n.d., https://elib.biblioatom.ru/soviet-atomic-program/ (accessed January 3, 2024).

17. Kassenova, Atomic Steppe, p. 6.

18. Nuclear Truth Project, “Challenging Nuclear Secrecy,” p. 7.

19. See U.S. Department of Energy, “Openness Information Resources,” n.d., https://www.osti.gov/opennet/press (accessed January 3, 2024).

20. Patrick Kaiku, “Nuclear Justice for the Marshall Islands in the Age of Geopolitical Rivalry in the Pacific,” Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, August 2023, p. 13, https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Patrick-Kaiku_August-2023.pdf.

21. Nuclear Truth Project, “Challenging Nuclear Secrecy,” p. 11.

22. The Public Interest Declassification Board, “Declassification of Records Relating to Nuclear Weapons Testing and Cleanup Activities in the Marshall Islands: Feasibility Study,” August 2022, https://www.archives.gov/files/pidb/recommendations/marshall-islands-feasibility-study-2022-.pdf.

23. Statement of Switzerland to the second meeting of TPNW states-parties, November 30, 2023, p. 2, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/2msp/statements/30Nov_Switzerland_A6.pdf.

24. Chris Reus-Smit and Ayşe Zarakol, “The Crisis of International Order: Is It About Injustice?” Medium, January 17, 2023, https://medium.com/international-affairs-blog/the-crisis-of-international-order-is-it-about-injustice-8cbcada5aa33.

25. See Second Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, “Policy Recommendations on Trust Fund, International Cooperation, Articles 6 and 7, Preamble, and Article 1,” TPNW/MSP/2023/NGO/4, November 14, 2023, p. 3; Second Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, “Challenging Nuclear Secrecy: Barriers to Access and Ethics of Nuclear Archives,” TPNW/MSP/2023/NGO/9, November 14, 2023.

26. National Nuclear Center of the Republic of Kazakhstan, “Draft Law About ‘Semipalatinsk Nuclear Safety Zone,’” June 2, 2022, https://www.nnc.kz/en/news/show/372.

27. Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan, “On the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Safety Zone,” December 28, 2023, https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/Z2300000016.

Ekaterina Lapanovich is a senior lecturer at Ural Federal University. Laura Lepsy is a consultant on peace, security, and international cooperation issues. Alain Ponce Blancas is a research and communication officer at the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean. All three contributors are alumni of the Arms Control Negotiation Academy at Harvard University Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

How the winner of the 2024 race will handle the evolving array of nuclear weapons-related challenges is difficult to forecast, but the records and policies of the leading contenders, President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, offer clues.

How the winner of the 2024 race will handle the evolving array of nuclear weapons-related challenges is difficult to forecast, but the records and policies of the leading contenders, President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, offer clues.

Although a positive step, the consultation’s long-term impact will be contingent on the arrangement of subsequent meetings in an institutionalized setting. For these meetings to transcend symbolism and address substantive issues of concern, it will be essential to include representatives of the Chinese defense policy establishment and, ideally, military officials alongside the usual foreign

Although a positive step, the consultation’s long-term impact will be contingent on the arrangement of subsequent meetings in an institutionalized setting. For these meetings to transcend symbolism and address substantive issues of concern, it will be essential to include representatives of the Chinese defense policy establishment and, ideally, military officials alongside the usual foreign Many Chinese nuclear policy experts find themselves perplexed by the logic and rationale behind this unprecedented nuclear expansion. This confusion raises concerns that the shift in China’s nuclear policy may be more reflective of the top leader’s political instincts rather than a carefully considered strategy aligned with a clearly defined consensus goal within the policy community. In a system of open and free debate, Chinese leaders might have recognized that China’s buildup could trigger U.S. responses, potentially deteriorating China’s security environment. Yet, basic scrutiny of strategic decisions is becoming increasingly challenging.

Many Chinese nuclear policy experts find themselves perplexed by the logic and rationale behind this unprecedented nuclear expansion. This confusion raises concerns that the shift in China’s nuclear policy may be more reflective of the top leader’s political instincts rather than a carefully considered strategy aligned with a clearly defined consensus goal within the policy community. In a system of open and free debate, Chinese leaders might have recognized that China’s buildup could trigger U.S. responses, potentially deteriorating China’s security environment. Yet, basic scrutiny of strategic decisions is becoming increasingly challenging. The United States finds it challenging, however, to accept the concept of mutual vulnerability, such as through a mutual renunciation of the first use of nuclear weapons, even if such an agreement could be reliably verified. Washington harbors concerns that Beijing might exploit such an agreement to carry out strategic non-nuclear attacks that could threaten core U.S. interests. Consequently, Washington believes that it has a legitimate reason to preserve the option of nuclear first use as a deterrent and potential response to such attacks.

The United States finds it challenging, however, to accept the concept of mutual vulnerability, such as through a mutual renunciation of the first use of nuclear weapons, even if such an agreement could be reliably verified. Washington harbors concerns that Beijing might exploit such an agreement to carry out strategic non-nuclear attacks that could threaten core U.S. interests. Consequently, Washington believes that it has a legitimate reason to preserve the option of nuclear first use as a deterrent and potential response to such attacks. Looking back, it is clear that nuclear arms control reached an apogee in the 1990s with the first and second strategic arms reduction treaties between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia and with multilateral agreements such as the Open Skies Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).

Looking back, it is clear that nuclear arms control reached an apogee in the 1990s with the first and second strategic arms reduction treaties between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia and with multilateral agreements such as the Open Skies Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). The TPNW directly challenges deterrence with its prohibition on the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons. This principle enabled treaty member states to issue a strong condemnation of nuclear threats at their first meeting in 2022, following Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling regarding Ukraine. The TPNW language has been echoed since by the Group of 20 countries and by individual leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg.

The TPNW directly challenges deterrence with its prohibition on the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons. This principle enabled treaty member states to issue a strong condemnation of nuclear threats at their first meeting in 2022, following Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling regarding Ukraine. The TPNW language has been echoed since by the Group of 20 countries and by individual leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg. This is the way a survivor described in the book Atomic Steppe how the inhabitants of Karaul, located around 95 kilometers from the former Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan, experienced the day of the first Soviet thermonuclear test.

This is the way a survivor described in the book Atomic Steppe how the inhabitants of Karaul, located around 95 kilometers from the former Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan, experienced the day of the first Soviet thermonuclear test. The format encourages states-parties to provide specific data based on the same criteria so that the data can be processed and analyzed systematically. Reporting questions also address epistemic standards related to measuring the effects of nuclear tests, such as the methodology of assessment and criteria used to define victimhood. The format therefore confronts two major barriers to effective victim assistance and environmental remediation: the scarcity of systematic data and the absence of universal standards for defining victimhood.

The format encourages states-parties to provide specific data based on the same criteria so that the data can be processed and analyzed systematically. Reporting questions also address epistemic standards related to measuring the effects of nuclear tests, such as the methodology of assessment and criteria used to define victimhood. The format therefore confronts two major barriers to effective victim assistance and environmental remediation: the scarcity of systematic data and the absence of universal standards for defining victimhood. If TPNW states want nuclear-weapon states to support the victim assistance and environmental remediation agenda, the TPNW framework or even the NPT might not be viable for the time being. Instead, an international conference on the legacy of nuclear testing with a technical expert-level focus might be a better mechanism to strike the balance between securing the nuclear-weapon states’ commitment and yielding benefits for testing-affected states.

If TPNW states want nuclear-weapon states to support the victim assistance and environmental remediation agenda, the TPNW framework or even the NPT might not be viable for the time being. Instead, an international conference on the legacy of nuclear testing with a technical expert-level focus might be a better mechanism to strike the balance between securing the nuclear-weapon states’ commitment and yielding benefits for testing-affected states. Two years before that visit, bipartisan majorities in Congress, acting over the objections of the George H.W. Bush administration, approved legislation mandating a nine-month U.S. nuclear test moratorium in response to a Soviet testing moratorium declared in October 1991. In 1993, President Bill Clinton, following intensive interagency consultations, decided that further nuclear testing was not necessary. He would extend the U.S. nuclear test moratorium, establish the Stockpile Stewardship Program to maintain the arsenal without testing, and pursue multilateral negotiations for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) (see box).

Two years before that visit, bipartisan majorities in Congress, acting over the objections of the George H.W. Bush administration, approved legislation mandating a nine-month U.S. nuclear test moratorium in response to a Soviet testing moratorium declared in October 1991. In 1993, President Bill Clinton, following intensive interagency consultations, decided that further nuclear testing was not necessary. He would extend the U.S. nuclear test moratorium, establish the Stockpile Stewardship Program to maintain the arsenal without testing, and pursue multilateral negotiations for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) (see box). lthough not yet formally entered into force because the treaty requires that the United States and eight other specific states ratify it, the CTBT, which now has 187 signatories, has established a de facto halt to nuclear testing. It has become one of the most successful and valuable agreements in the long history of nuclear nonproliferation, arms control, and disarmament. Today, no state is conducting nuclear test explosions. North Korea is the only country to have done so in this century. Without the option to conduct nuclear tests, it is more difficult, although not impossible, to develop, prove, and field new warhead designs.

lthough not yet formally entered into force because the treaty requires that the United States and eight other specific states ratify it, the CTBT, which now has 187 signatories, has established a de facto halt to nuclear testing. It has become one of the most successful and valuable agreements in the long history of nuclear nonproliferation, arms control, and disarmament. Today, no state is conducting nuclear test explosions. North Korea is the only country to have done so in this century. Without the option to conduct nuclear tests, it is more difficult, although not impossible, to develop, prove, and field new warhead designs. The massive Sedan Crater, the product of a misguided “peaceful nuclear explosions” program from 1961 to 1973, still stands out as a stunning reminder of the destructive power of nuclear weapons and the excesses of the Cold War-era nuclear weapons establishment. The program was intended to explore the use of nuclear bomb explosions to create canals and expand harbors and to stimulate natural gas production.

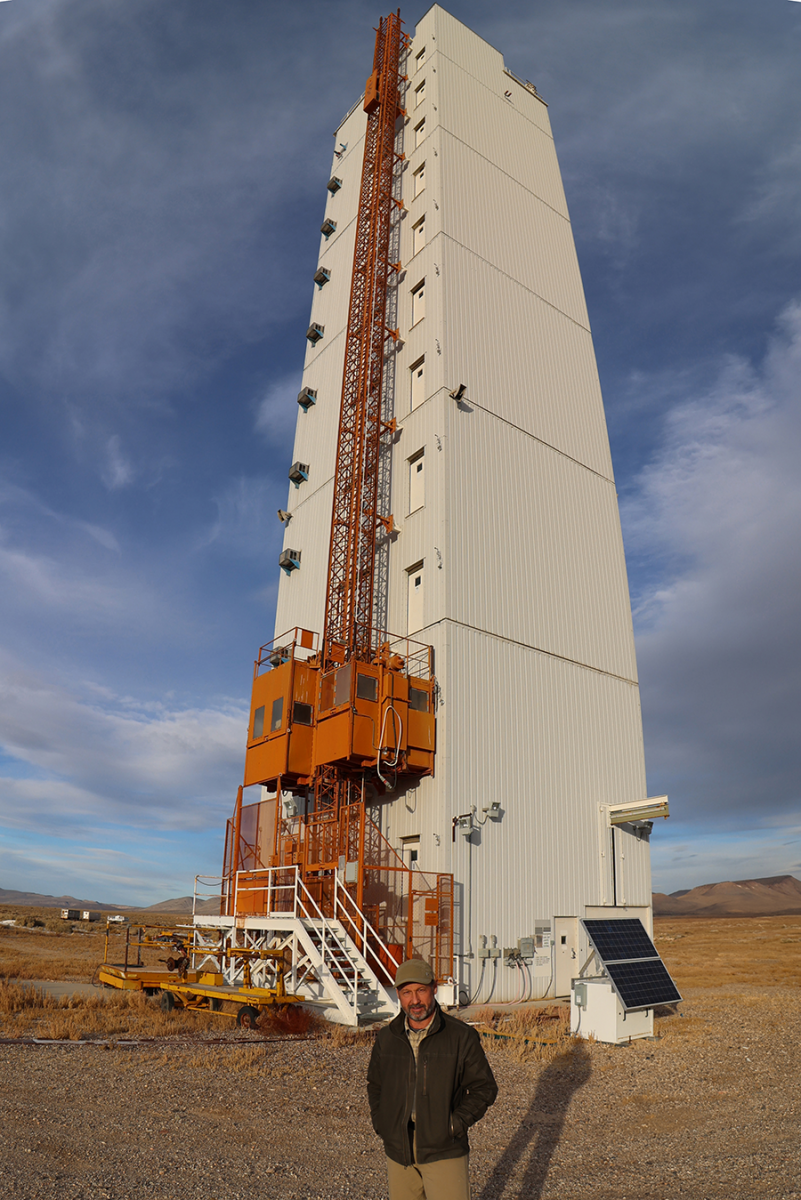

The massive Sedan Crater, the product of a misguided “peaceful nuclear explosions” program from 1961 to 1973, still stands out as a stunning reminder of the destructive power of nuclear weapons and the excesses of the Cold War-era nuclear weapons establishment. The program was intended to explore the use of nuclear bomb explosions to create canals and expand harbors and to stimulate natural gas production. Originally, subcritical experiments were conducted in single-use alcoves mined into the walls or in vertical boreholes in the floor of the U1A complex. Our group walked over several of the metal seals that today cover the boreholes from some of these experiments. In more recent years, the experiments have been conducted in a robust confinement vessel located in an isolated “zero room,” which prevents the release of radiological material and conserves space in the underground facility.

Originally, subcritical experiments were conducted in single-use alcoves mined into the walls or in vertical boreholes in the floor of the U1A complex. Our group walked over several of the metal seals that today cover the boreholes from some of these experiments. In more recent years, the experiments have been conducted in a robust confinement vessel located in an isolated “zero room,” which prevents the release of radiological material and conserves space in the underground facility. South Korea announced on Nov. 22 that it will no longer abide by a no-fly zone established over the border area between the two Koreas in the Comprehensive Military Agreement. That agreement, concluded in September 2018 between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, also contains restrictions on guard posts and live-fire exercises near the Demilitarized Zone between the two countries.

South Korea announced on Nov. 22 that it will no longer abide by a no-fly zone established over the border area between the two Koreas in the Comprehensive Military Agreement. That agreement, concluded in September 2018 between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, also contains restrictions on guard posts and live-fire exercises near the Demilitarized Zone between the two countries. At their second annual TPNW meeting held Nov. 27 to Dec. 1 in New York, they approved a political outcome document that unveiled the new strategy, declaring that the states-parties “will not stand by as spectators to increasing nuclear risks and the dangerous perpetuation of nuclear deterrence.”

At their second annual TPNW meeting held Nov. 27 to Dec. 1 in New York, they approved a political outcome document that unveiled the new strategy, declaring that the states-parties “will not stand by as spectators to increasing nuclear risks and the dangerous perpetuation of nuclear deterrence.” Over the years, as awareness increased about the full effects of these activities and new lawsuits were filed against the U.S. government related to radiation exposure claims, RECA’s narrow scope of coverage was broadened to include more affected communities.

Over the years, as awareness increased about the full effects of these activities and new lawsuits were filed against the U.S. government related to radiation exposure claims, RECA’s narrow scope of coverage was broadened to include more affected communities. In a Dec. 26 report, the IAEA noted that Iran is now producing approximately nine kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent uranium-235 per month. Iran was producing 60 percent enriched U-235 at a similar rate in early 2023, but decreased production by about two-thirds in June. (See

In a Dec. 26 report, the IAEA noted that Iran is now producing approximately nine kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent uranium-235 per month. Iran was producing 60 percent enriched U-235 at a similar rate in early 2023, but decreased production by about two-thirds in June. (See  The administration did not request any funding for the nuclear SLCM in 2023 or 2024 because it assessed that the weapon has only “marginal utility” and would “impede investment in other priorities.” (See

The administration did not request any funding for the nuclear SLCM in 2023 or 2024 because it assessed that the weapon has only “marginal utility” and would “impede investment in other priorities.” (See