July/August 2019

By Frank N. von Hippel and Sharon K. Weiner

In October 2018, the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) announced its decision to reestablish a domestic uranium-enrichment capability in the United States.1 As described in its fiscal year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, the NNSA said there is a pending shortage of U.S.-origin low-enriched uranium (LEU) needed to fuel the nuclear reactors that produce the tritium gas used in U.S. nuclear weapons. The NNSA initially estimated a need for new supplies of LEU by 2027, but after an internal review identified additional materials, this date was deferred until at least 2038.2

The U.S. Department of Energy, in which the NNSA operates, also sees a need to produce high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU)3 for the new, small, modular power reactors it argues are central to reviving the U.S. nuclear energy sector. In the longer term, the NNSA argues that an enrichment facility will be needed by 2060 to produce the highly enriched uranium (HEU) used to fuel the reactors that power the Navy’s submarines and aircraft carriers.4

The U.S. Department of Energy, in which the NNSA operates, also sees a need to produce high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU)3 for the new, small, modular power reactors it argues are central to reviving the U.S. nuclear energy sector. In the longer term, the NNSA argues that an enrichment facility will be needed by 2060 to produce the highly enriched uranium (HEU) used to fuel the reactors that power the Navy’s submarines and aircraft carriers.4

There are a number of reasons to question the NNSA’s urgency to build an enrichment facility. The United States still has a large surplus of Cold War-era HEU that could be blended down to LEU and could significantly delay the need to enrich LEU for tritium production. Additionally, it might be possible to purchase LEU from the European enrichment services company, Urenco, which operates the only uranium-enrichment plant in the United States. An agreement could be made, as France and Urenco have done, to allow the United States to use Urenco-enriched uranium for military but non-explosive purposes. Urenco also has announced that it plans to produce HALEU, which it could do at a much lower price than the Energy Department’s proposed small, expensive facility that could cost $10 billion or more.

The NNSA’s plans also ignore arguments for fueling future naval propulsion reactors with LEU, which would negate the need for HEU production. Making more HEU for naval reactors sets an undesirable precedent for non-nuclear-armed states such as Brazil, Iran, and South Korea, which are developing nuclear submarines or considering doing so. Unlike LEU, HEU can be used to make nuclear weapons directly, even by terrorist groups.

Credible alternatives exist. The United States should seriously consider those alternatives before investing in a new uranium-enrichment capability.

The NNSA Case for Enrichment

The NNSA argument for building a national enrichment capability begins with tritium, a gas used in two-stage nuclear weapons to boost the power of fission-based triggers, ensuring the ignition of the fission-fusion second stage. With a radioactive half-life of 12.3 years, tritium needs to be regularly replenished in U.S. weapons to maintain the intended yield.

Some of the supplies to meet current and future needs come from the reduction of the U.S. nuclear arsenal after the end of the Cold War. The NNSA has downblended the HEU from dismantled weapons into LEU that is used for tritium production.

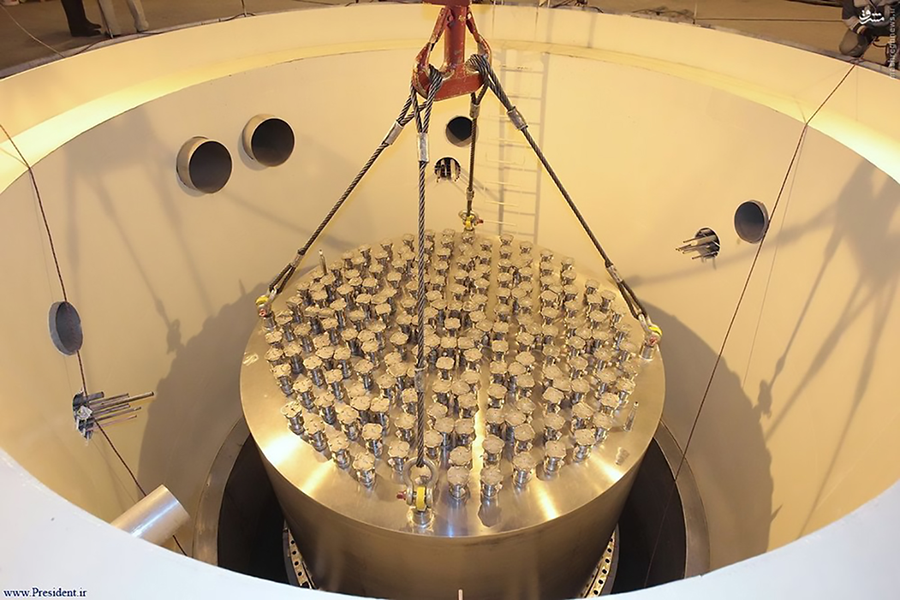

New tritium is produced in a Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) reactor at the Watts Bar Power Plant in Tennessee; a second reactor there is expected to start producing in 2020. Tritium-producing burnable absorber rods containing lithium-6 are inserted into the reactor fuel assemblies, where they stay for about 18 months. When the reactors are refueled, the rods are removed, and the tritium is extracted at a facility at the Energy Department’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina.

At issue is the availability of “unobligated” LEU to fuel the tritium-production reactors. The NNSA and the Department of State insist that peaceful-use trade agreements prevent the United States from using LEU that has been produced from foreign uranium, or enriched in a foreign-owned plant or in a U.S. plant using foreign enrichment technology. The NNSA argues that any tritium generated from these “obligated” sources is off-limits and therefore more unobligated LEU is needed.

The United States stopped making HEU for nuclear weapons in 1964 and ended the production of unobligated LEU in 2013 when it closed the last of its Cold War gaseous-diffusion uranium-enrichment plants. The LEU used for current tritium production comes from uranium previously enriched in these facilities, including some of the 374 metric tons of HEU the United States declared excess to its weapons requirements in 1994 and 2005. Of this excess Cold War HEU, 152 metric tons of weapons-grade uranium were set aside to fuel Navy nuclear reactors, and 28 metric tons have been made available to be diluted down to LEU fuel for tritium production.5

This Cold War enriched uranium is a finite resource. The NNSA projects that the United States will run out of unobligated LEU for tritium production between 2038 and 2041 and that the HEU that has been set aside for naval reactors will run out around 2060.6 Because the United States does not have experience building modern gas-centrifuge enrichment facilities, the NNSA argues that it would be wise to start building soon.

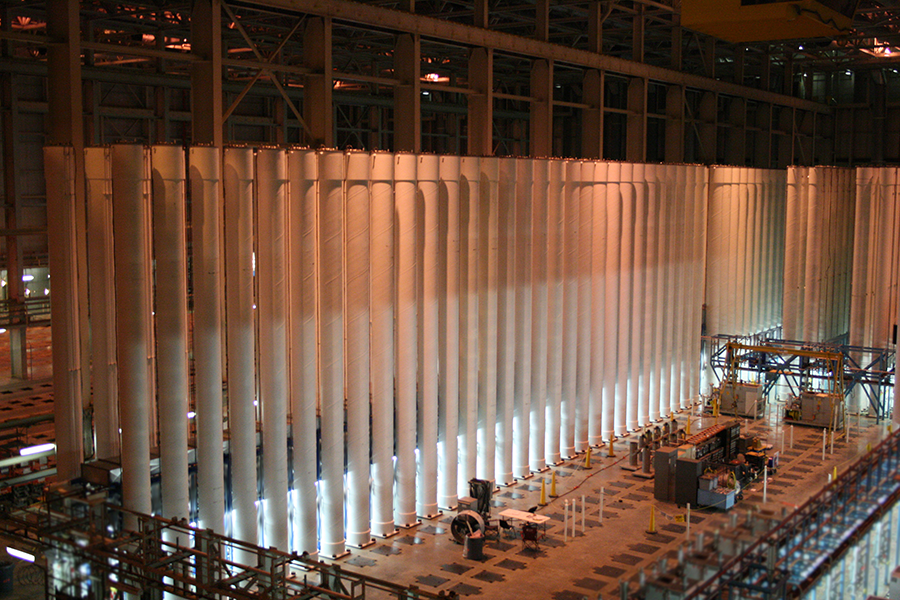

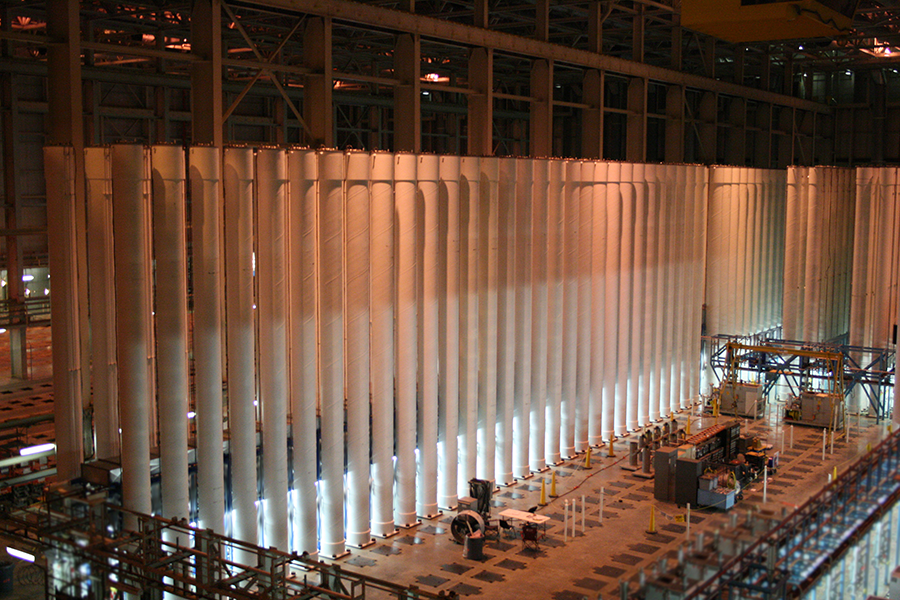

The NNSA established the mission need for a domestic uranium-enrichment facility in fiscal year 2017 and has funded development of two technologies.7 One would use AC100 centrifuges developed jointly by the NNSA and the United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC) and USEC’s successor, Centrus Energy. The AC100 is the world’s largest gas centrifuge and has a capacity to produce about 340 separative work units (SWUs) per year.8

The NNSA established the mission need for a domestic uranium-enrichment facility in fiscal year 2017 and has funded development of two technologies.7 One would use AC100 centrifuges developed jointly by the NNSA and the United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC) and USEC’s successor, Centrus Energy. The AC100 is the world’s largest gas centrifuge and has a capacity to produce about 340 separative work units (SWUs) per year.8

USEC, a private corporation, operated two U.S. gaseous-diffusion plants and acted as a broker for down-blended Russian HEU from 1993 until 2013, when USEC went bankrupt. Renamed Centrus Energy and with former Deputy Energy Secretary Daniel Poneman as its president and chief executive officer, the company continues as a uranium broker for Russian LEU while lobbying for Energy Department funding to build a gas-centrifuge enrichment plant. In 2009 the Energy Department turned down a USEC request for a $2 billion loan guarantee to build a commercial enrichment facility, but has issued a notice of intent to contract with Centrus Energy to develop the capability to produce HALEU using AC100 centrifuges.

The NNSA is also funding the development of smaller, more conventional centrifuges designed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

According to NNSA estimates, building a domestic enrichment capability for tritium production would cost between $3.1 billion and $11.3 billion using the AC100 centrifuge and between $3.2 billion and $6.8 billion using the smaller centrifuge. Adding capacity to produce HEU for naval reactor fuel would increase the cost significantly.

A 2018 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) raises some concerns about NNSA plans and cost estimates. The GAO states that the NNSA’s preliminary analysis of options for meeting enrichment needs was biased toward establishing a new enrichment capability and did not sufficiently consider alternatives.9 In addition, the GAO found that the NNSA cost-estimating process did not meet best practices. The NNSA has consistently been on the GAO list of agencies with projects at “high risk” for cost increases and schedule delays because of contract management problems. If past NNSA cost overruns are any indicator, a domestic enrichment capability could cost significantly more than current NNSA estimates.10

This makes it even more important to consider three credible alternatives. First, the need for a new, national uranium-enrichment program could be delayed by declaring additional HEU to be excess to U.S. weapons needs. Second, it might be made altogether unnecessary if the NNSA were willing to purchase uranium-enrichment services from Urenco. Finally, the United States could eliminate any future need for producing additional weapons-grade uranium by designing future nuclear submarines to be fueled by LEU.

Declaring Additional HEU Excess

The NNSA’s review of potential alternative sources of unobligated LEU was not authorized to consider the possibility that the United States might be in a position to declare as excess additional HEU-containing weapon components.

The NNSA has not issued recent public information, but an estimate of the amount of HEU currently in the U.S. weapons stockpile can be made from past declarations by using a detailed report on U.S. stocks of HEU available for weapons as of September 30, 1996, and subtracting material declared to be excess for weapons in 2005 and an estimate of the amount of scrap HEU declared to be excess in 2015. This data suggests the United States has in nuclear weapons, weapons components, and reserves available for nuclear weapons between 216 and 240 tons of weapons-grade HEU containing about 200 to 225 tons of uranium-235.11

Based on the official September 2017 declaration that the U.S. nuclear stockpile contained 3,822 operational warheads, less than half of this HEU is used in operational U.S. nuclear warheads. If each of these operational warheads contained an average of 25 kilograms of HEU, a conservatively high estimate, then today’s entire arsenal would contain about 93.5 tons of U-235. That would leave more than 100 tons of weapons-grade uranium not in operational warheads.

If the United States declared 40 tons of weapons-grade uranium from this reserve to be excess and blended it down with natural uranium to 1,000 tons of 4.5 percent-enriched LEU, that would be sufficient to fuel the two Watts Bar tritium-production reactors for another 20 years, until about 2060 when the Navy’s reserve of HEU would be depleted as well.

Enrichment Services From Urenco

The Energy Department argues that the United States cannot fuel its tritium-producing reactors with LEU enriched in foreign-owned plants because all foreign material is obligated not to be used for weapons purposes under international supply agreements. Interestingly, Urenco does not agree.

The peaceful-use article in the treaty among the United States and the three nations (Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) that own Urenco’s commercial enrichment plant in New Mexico states that “[a]ny centrifuge technology, equipment and components transferred into the United States subject to this agreement,… any nuclear material…, any special nuclear material produced through the use of such technology, any special nuclear material produced through the use of such special nuclear material…shall only be used for peaceful, non-explosive purposes.”12 “Special nuclear material” is defined in the agreement as “plutonium, uranium-233, and uranium enriched in the isotopes U-233 or U-235.” Tritium is not included.

A 2014 GAO report on the topic stated that it was Urenco’s position that the use of Urenco-produced LEU to fuel the TVA tritium-production reactors would be allowed by the treaty: “Urenco has consistently informed TVA that it places no restrictions on TVA using [Urenco’s] LEU in its tritium-producing reactors.”13

Therefore, although the seller is willing, the buyer is not.

The GAO noted that the strict U.S. interpretation of its peaceful-use commitments was established in 1998 when USEC was still producing LEU. It also noted that the key agencies involved in this discussion, the Energy and State departments, argued that having a national enrichment plant would further U.S. nonproliferation and national security goals. According to the GAO, the Energy Department argued, for example, that “if the United States were to permanently lose its domestic enrichment capability, it could cause concern among other countries that the United States may not be able to ensure a guaranteed LEU supply, and other countries may then seek to acquire their own indigenous enrichment capability. This could, in turn, create new proliferation concerns, as the use of sensitive nuclear fuel enrichment technologies that are used to develop LEU for nuclear fuel could also be used for a clandestine nuclear weapons program.”

On the other hand, it could be argued that the United States could strengthen the nonproliferation regime by setting the example of forgoing a national enrichment program in favor of a multinational program. The current international supply of enrichment services is quite diverse (China, France, Russia, Urenco), and supply significantly exceeds demand. Currently, only three non-nuclear-armed states have active enrichment programs: Brazil, for its nuclear submarine program; Iran, with a program that has been a major focus of proliferation concern; and Japan. Each of these programs is uneconomic and currently too small to support even one large power reactor.

On the other hand, it could be argued that the United States could strengthen the nonproliferation regime by setting the example of forgoing a national enrichment program in favor of a multinational program. The current international supply of enrichment services is quite diverse (China, France, Russia, Urenco), and supply significantly exceeds demand. Currently, only three non-nuclear-armed states have active enrichment programs: Brazil, for its nuclear submarine program; Iran, with a program that has been a major focus of proliferation concern; and Japan. Each of these programs is uneconomic and currently too small to support even one large power reactor.

The Energy Department has suggested that a government-funded facility created for national security purposes could have surplus capacity to produce LEU for the commercial market.14 Given the Energy Department’s estimated costs for building and operating the plant, however, even without the huge cost overruns typical for new nuclear facilities, the production cost per SWU for the NNSA plant would be 15 to 40 times greater than the current market price.15

The NNSA argues that, in the long run, the United States will need a national enrichment facility to make HEU for naval reactor fuel. Even here, however, foreign centrifuges might be used. France, for example, already enriches uranium for its naval reactors with centrifuges produced by Enrichment Technology Company (ETC), a company owned jointly by Urenco and France’s fuel-cycle corporation, Orano. The peaceful-use paragraph in the Treaty of Cardiff under which France bought a share of ETC appears to have been designed to allow this: “The Government of the French Republic shall ensure that any organization which builds plants for the enrichment of uranium on the territory of the French Republic using or otherwise exploiting Centrifuge Technology owned by, held by, or deriving or arising from the operations of, ETC, or operates such plants, shall not produce weapons-grade uranium for the manufacture of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.”16

This limitation would appear to allow uranium enrichment for naval reactor fuel even up to the level of weapons grade. Because it did not want to go to the extra expense of higher enrichment just for its naval reactors, however, France fuels its nuclear submarines and nuclear aircraft carrier with LEU produced at Orano’s Georges Besse II plant, which produces primarily LEU for power reactor fuel. Enrichment of the LEU produced at Georges Besse II is limited to 6 percent.

In principle, if the United States could get the same terms with Urenco and Orano as France did, this could open up the possibility of buying enriched uranium for U.S. naval reactors from Urenco as well. Some would argue that Urenco and ETC, which produces its centrifuges, are foreign-controlled companies, but the controlling governments are all U.S. allies. Urenco’s U.S. subsidiary is incorporated in Delaware, its plant is in the United States, and virtually all its employees are Americans. The risk that somehow the United States would be cut off from its naval fuel supply seems remote.

In any case, the U.S. supply of enriched uranium for national security missions could be buffered by large stockpiles that would provide ample time for the United States to build an alternative enrichment plant if something should go awry. If this is not sufficient assurance, a U.S. company might be encouraged by the government to buy a share of Urenco. The Netherlands, the UK, and the two utilities that own Germany’s share of Urenco have been expressing an interest in selling for years.17 The market value of $10 billion estimated for the company in 2013, is within the $3.1–11.3 billion range estimated by the Energy Department for construction of a facility equipped with AC100 centrifuges with an enrichment capacity of 0.4 million SWUs per year. Urenco’s enrichment capacity is nearly 50 times larger.18

Future Submarines and LEU

All U.S. submarines and aircraft carriers are fueled by weapons-grade uranium containing 93.5 percent U-235. There are technical advantages to HEU fuel, including more compact, longer-lived reactor cores. Yet, global trends are moving away from the use of HEU because the material can also be used directly to make nuclear weapons, even by terrorist groups. After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the United States led a largely successful global campaign to end the use of HEU to fuel research reactors.

The technical trade-offs for the benefits of moving naval reactors to LEU fuel would be acceptable.19 France has quietly switched its submarines and aircraft carrier to use LEU fuel, mostly for cost reasons, and China has reportedly always used LEU.20 That leaves the United States; the UK, which bases its naval reactors on U.S. designs; Russia; and India, which bases its naval reactors on Russian designs.

The U.S. nuclear navy believes that it could switch its aircraft carriers to LEU but argues that it would have to design its future submarine reactors to hold larger cores or go back to midlife refueling.21 So, there is a trade-off between strengthening nonproliferation and nuclear security efforts by banning the production of HEU for any purpose and continuing to design future U.S. submarine reactors to run on HEU fuel.

If the United States designed its future naval reactors to operate on LEU, that could provide an extra incentive for the Urenco countries and France to renegotiate the treaty terms between the United States and Urenco. Rather than the 6 percent-enriched level that France has adopted for its naval reactor fuel, the United States could use the same fuel to which research reactors were converted to use: 19.75 percent-enriched, just below the 20 percent HEU threshold.

Uranium Enrichment Can Wait

In 1964, as part of an effort to reduce tensions with the Soviet Union after the Cuban missile crisis, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev announced parallel reductions in the production of fissile materials. In addition to promoting a more peaceful “post-Cold War era,” Johnson warned that the United States must not operate a nuclear project “just to maintain employment.”22 That same year, Johnson ordered an end to the production of enriched uranium for weapons purposes. For Johnson, the focus had shifted from weapons production to concerns about more countries getting the bomb.

Since 1974, when India tested a nuclear explosive made with plutonium separated for its civilian nuclear research and development program, the United States has discouraged non-nuclear-armed states from launching plutonium-separation or uranium-enrichment programs and argued for a shift from HEU to LEU in research reactors so as to minimize their proliferation potential and reduce terrorist access to nuclear materials. Given the options of down-blending more excess HEU and Urenco’s offer to supply LEU for U.S. tritium-production reactors and the feasibility of designing future U.S. naval reactors to use LEU fuel, the United States can afford to wait and consider the alternatives before building a national enrichment plant.

The authors would like to acknowledge Henry Sokolski of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center for his work on this subject. See https://www.weeklystandard.com/henry-sokolski/national-security-and-crony-nuclear-capitalism.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), “Fiscal Year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan - Biennial Plan Summary: Report to Congress,” DOE/NA-0072, October 2018, pp. 2–16.

2. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “NNSA Should Clarify Long-Term Uranium Enrichment Mission Needs and Improve Technology Cost Estimates,” GAO-18-126, February 2018, p. 14.

3. Instead of the 4 to 5 percent-enriched fuel of conventional power reactors, this uranium would be closer to the 20 percent-enrichment level above which enriched uranium is officially considered weapons usable.

4. U.S. Department of Energy, “Tritium and Enriched Uranium Management Plan Through 2060: Report to Congress,” October 2015, p. 26, http://fissilematerials.org/library/doe15b.pdf.

5. Ibid., fig. 2. All of the 174 tons of the highly enriched uranium (HEU) declared to be excess in 1994 was restricted to peaceful uses and therefore is not available for tritium production. Twenty tons of HEU declared to be excess in 2005 has been committed to be down-blended to high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) for research reactors.

6. NNSA, “Fiscal Year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan,” pp. 3–38.

7. GAO, “NNSA Should Clarify...,” pp. 23–27.

8. Separative work units (SWUs) are used to measure enrichment capacity and embedded enrichment work. It takes about 200 SWUs to produce a kilogram of 90 percent-enriched HEU, 8 SWUs for a kilogram of 5 percent-enriched low-enriched uranium (LEU), and 40 SWUs for a kilogram of 19.75 percent-enriched HALEU.

9. GAO, “NNSA Should Clarify...”

10. Lydia Dennett, “Nuke Agency Needs Budget Accountability,” Project on Government Oversight, May 1, 2018, https://www.pogo.org/investigation/2018/05/nuke-agency-needs-budget-accountability/; David Kramer, “DOE Uranium Contract Raises Fairness Concerns,” Physics Today, Vol. 72, No. 3 (2019), pp. 28–30.

11. Frank von Hippel, “Declaring More U.S. Weapon-Grade Uranium Excess Could Delay by Two Decades the Need to Build a New National Enrichment Plant,” April 5, 2018, http://fissilematerials.org/library/fvh18.pdf.

12. “Agreement Between the Three Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Federal Republic of Germany and the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Government of the United States of America Regarding the Establishment, Construction and Operation of a Uranium Enrichment Installation in the United States,” February 1, 1995, art. III.

13. “Urenco has consistently informed [the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)] that it places no restrictions on TVA using [Urenco’s] LEU in its tritium-producing reactors.” GAO, “Department of Energy: Interagency Review Needed to Update U.S. Position on Enriched Uranium That Can Be Used for Tritium Production,” GAO-15-123, October 2014, p. 30.

14. U.S. Department of Energy, “Tritium and Enriched Uranium Management Plan Through 2060,” p. 33.

15. The NNSA estimated that the capital cost of a facility built by Centrus Energy with a capacity of 400,000 SWUs per year would be $3.1 billion to $11.3 billion, with an annual operating cost of $112 million to $195 million. U.S. Department of Energy, “Tritium and Enriched Uranium Management Plan Through 2060,” pp. 32–38. Assuming a 30-year lifetime for the facility and a real inflation rate of 1.5 percent, the annual capital charge would be about 4 percent, and the cost of an SWU would be $590 to $1,600. For comparison, during 2018–2019, the average spot price for enrichment contracts was about $40 per SWU.

16. “Agreement Between the Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic Regarding Collaboration in Centrifuge Technology,” July 12, 2005, art. IV.2.

17. Stanley Reed, “Powerhouse of the Uranium Enrichment Industry Seeks an Exit,” The New York Times, May 27, 2013.

18. Urenco’s annual enrichment capacity is 18.6 million SWUs. Urenco, “Global Operations,” n.d., https://urenco.com/global-operations (accessed June 14, 2019).

19. Sebastien Philippe and Frank von Hippel, “The Feasibility of Ending HEU Fuel Use in the U.S. Navy,” Arms Control Today, November 2016, pp. 15–22.

20. Hui Zhang, “China’s Fissile Material Production and Stockpile,” International Panel on Fissile Materials Research Report, No. 17 (December 2017), p. 16, http://fissilematerials.org/library/rr17.pdf.

21. NNSA, “Conceptual Research and Development Plan for Low-Enriched Uranium Naval Fuel: Report to Congress,” July 2016.

22. “Design for Peace,” The Washington Post, April 21, 1964, p. A14.

Frank N. von Hippel is a professor emeritus of public and international affairs in Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security. During 1993–1994, he served as assistant director for national security in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Sharon K. Weiner is an associate professor in American University’s School of International Service. During 2014–2017, she worked in the National Security Division of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Worse yet, Trump’s national security team has dithered for more than a year on beginning talks with Russia to extend the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) before it expires in February 2021. It is now apparent that Bolton is trying to steer Trump to discard New START.

Worse yet, Trump’s national security team has dithered for more than a year on beginning talks with Russia to extend the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) before it expires in February 2021. It is now apparent that Bolton is trying to steer Trump to discard New START.

The U.S. push for Iran to adhere to the deal’s terms has drawn some international incredulity given how the United States withdrew from agreement in May 2018 while noisily alleging many JCPOA flaws. More subtly, the Trump administration has begun to lay the groundwork for what can be described as its first real redline for the nuclear program: that any reduction in Iran’s one-year breakout timeline, the amount of time Iran would need to produce enough enriched uranium for a bomb, is unacceptable.

The U.S. push for Iran to adhere to the deal’s terms has drawn some international incredulity given how the United States withdrew from agreement in May 2018 while noisily alleging many JCPOA flaws. More subtly, the Trump administration has begun to lay the groundwork for what can be described as its first real redline for the nuclear program: that any reduction in Iran’s one-year breakout timeline, the amount of time Iran would need to produce enough enriched uranium for a bomb, is unacceptable. More worrying would be if Iran acts on its threat to increase enrichment levels as early as July. Depending on how high Iran goes, such as resuming enrichment to near 20 percent uranium-235, this could have a seriously adverse affect on Iran’s breakout timeline as this material accumulates. A U.S. decision to end sanctions waivers that allow Iran to import 20 percent-enriched fuel for its research reactor would make

More worrying would be if Iran acts on its threat to increase enrichment levels as early as July. Depending on how high Iran goes, such as resuming enrichment to near 20 percent uranium-235, this could have a seriously adverse affect on Iran’s breakout timeline as this material accumulates. A U.S. decision to end sanctions waivers that allow Iran to import 20 percent-enriched fuel for its research reactor would make The U.S. Department of Energy, in which the NNSA operates, also sees a need to produce high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU)

The U.S. Department of Energy, in which the NNSA operates, also sees a need to produce high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) The NNSA established the mission need for a domestic uranium-enrichment facility in fiscal year 2017 and has funded development of two technologies.

The NNSA established the mission need for a domestic uranium-enrichment facility in fiscal year 2017 and has funded development of two technologies. On the other hand, it could be argued that the United States could strengthen the nonproliferation regime by setting the example of forgoing a national enrichment program in favor of a multinational program. The current international supply of enrichment services is quite diverse (China, France, Russia, Urenco), and supply significantly exceeds demand. Currently, only three non-nuclear-armed states have active enrichment programs: Brazil, for its nuclear submarine program; Iran, with a program that has been a major focus of proliferation concern; and Japan. Each of these programs is uneconomic and currently too small to support even one large power reactor.

On the other hand, it could be argued that the United States could strengthen the nonproliferation regime by setting the example of forgoing a national enrichment program in favor of a multinational program. The current international supply of enrichment services is quite diverse (China, France, Russia, Urenco), and supply significantly exceeds demand. Currently, only three non-nuclear-armed states have active enrichment programs: Brazil, for its nuclear submarine program; Iran, with a program that has been a major focus of proliferation concern; and Japan. Each of these programs is uneconomic and currently too small to support even one large power reactor. Then I worked in New York at the United Nations from 1974 to 1979, and when I returned to Moscow, I was kind of lucky because at that time they were expanding the linguistic services of the Soviet Foreign Ministry. So, there were vacancies, and I was accepted to work there. Interestingly, one of my first assignments was to work at the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty] negotiations that started in 1981.

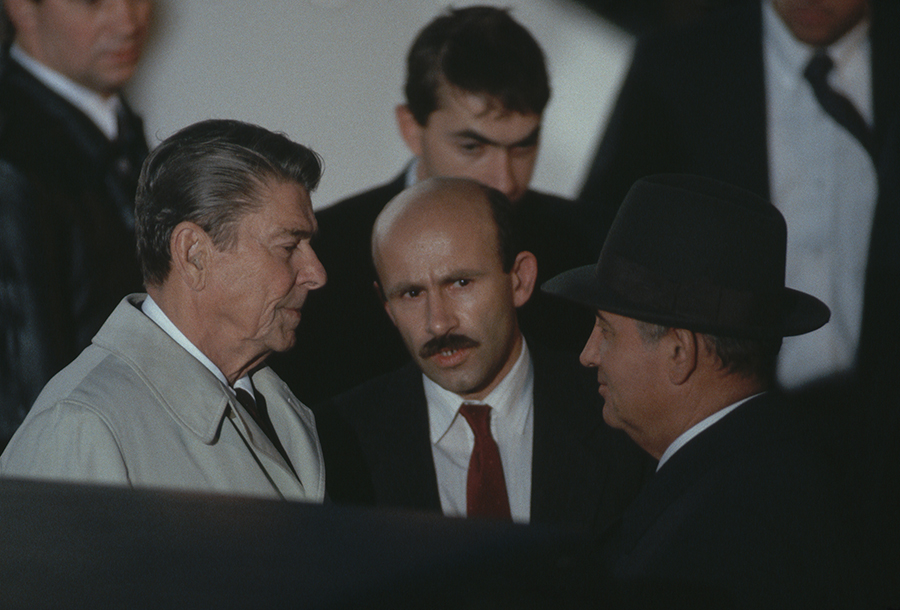

Then I worked in New York at the United Nations from 1974 to 1979, and when I returned to Moscow, I was kind of lucky because at that time they were expanding the linguistic services of the Soviet Foreign Ministry. So, there were vacancies, and I was accepted to work there. Interestingly, one of my first assignments was to work at the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty] negotiations that started in 1981. That was a bit of luck. I was fortunate that I was asked to do it. Then I continued both with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev. I interpreted Shevardnadze’s first meeting with President Ronald Reagan at the White House in September 1985, so the profile was high because at that time it was quite unusual. It was after a period of deep freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations, so there was a lot of media interest, so I guess that’s the reason.

That was a bit of luck. I was fortunate that I was asked to do it. Then I continued both with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev. I interpreted Shevardnadze’s first meeting with President Ronald Reagan at the White House in September 1985, so the profile was high because at that time it was quite unusual. It was after a period of deep freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations, so there was a lot of media interest, so I guess that’s the reason. Michael T. Klare’s article “An ‘Arms Race in Speed’: Hypersonic Weapons and the Changing Calculus of Battle” (

Michael T. Klare’s article “An ‘Arms Race in Speed’: Hypersonic Weapons and the Changing Calculus of Battle” ( In the summer of 1974, Albert Wohlstetter published a pair of articles in Foreign Policy that crystallized and fueled the national debate on nuclear policy. He challenged the conventional wisdom that the United States and Soviet Union were engaged in a nuclear arms race defined by overestimation and overreaction, as well as spiraling moves and countermoves. He asserted instead that the Soviet Union was rushing ahead while the United States ambled backward. A race, at least a fair one, requires matching paces. Yet, there can be no race, Wohlstetter wrote, “between parties moving in quite different directions.”

In the summer of 1974, Albert Wohlstetter published a pair of articles in Foreign Policy that crystallized and fueled the national debate on nuclear policy. He challenged the conventional wisdom that the United States and Soviet Union were engaged in a nuclear arms race defined by overestimation and overreaction, as well as spiraling moves and countermoves. He asserted instead that the Soviet Union was rushing ahead while the United States ambled backward. A race, at least a fair one, requires matching paces. Yet, there can be no race, Wohlstetter wrote, “between parties moving in quite different directions.” Culling declassified data from U.S. intelligence reports between 1962 and 1972, Wohlstetter concluded that the United States had chronically underestimated the number of nuclear weapons the Soviet Union would deploy. Through a buildup of ICBMs and strategic bombers, the Soviet Union had been surging forward, moving quickly from a position of strategic inferiority to one of rough parity with the United States. Contrary to the rhetoric of arms controllers, Washington was not overreacting to these developments with countervailing moves. Wohlstetter contended that U.S. strategic programs were actually in decline, with spending on offensive forces insufficient to meet the growing Soviet threat. Taken together, these findings painted an ominous picture of the strategic reality: Moscow was setting a pace that Washington neglected to match.

Culling declassified data from U.S. intelligence reports between 1962 and 1972, Wohlstetter concluded that the United States had chronically underestimated the number of nuclear weapons the Soviet Union would deploy. Through a buildup of ICBMs and strategic bombers, the Soviet Union had been surging forward, moving quickly from a position of strategic inferiority to one of rough parity with the United States. Contrary to the rhetoric of arms controllers, Washington was not overreacting to these developments with countervailing moves. Wohlstetter contended that U.S. strategic programs were actually in decline, with spending on offensive forces insufficient to meet the growing Soviet threat. Taken together, these findings painted an ominous picture of the strategic reality: Moscow was setting a pace that Washington neglected to match. In fact, the U.S.-North Korean summit that took place right here in Singapore a year ago was a historical meeting where President Trump and Chairman Kim agreed on a complete denuclearization of the peninsula and the improvement of bilateral relations, as well as mutual cooperation for the peace of the Korean Peninsula and the world.

In fact, the U.S.-North Korean summit that took place right here in Singapore a year ago was a historical meeting where President Trump and Chairman Kim agreed on a complete denuclearization of the peninsula and the improvement of bilateral relations, as well as mutual cooperation for the peace of the Korean Peninsula and the world. “Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard” outlined in the CTBT, said Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), in remarks to the Hudson Institute May 29.

“Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard” outlined in the CTBT, said Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), in remarks to the Hudson Institute May 29. If the United States were to formally withdraw its signature from the treaty, it would lose access to the nuclear test monitoring provided by the IMS, consisting of more than 300 seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound, and radionuclide sensor stations.

If the United States were to formally withdraw its signature from the treaty, it would lose access to the nuclear test monitoring provided by the IMS, consisting of more than 300 seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound, and radionuclide sensor stations. “There’s no decision, but I think it’s unlikely,” he told the Washington Free Beacon in an interview published June 18. His comments came less than a week after top U.S. and Russian arms control diplomats met in Prague to discuss the resumption of talks on strategic stability and the future of New START.

“There’s no decision, but I think it’s unlikely,” he told the Washington Free Beacon in an interview published June 18. His comments came less than a week after top U.S. and Russian arms control diplomats met in Prague to discuss the resumption of talks on strategic stability and the future of New START.