July/August 2023

By Toby Dalton and Ariel Levite

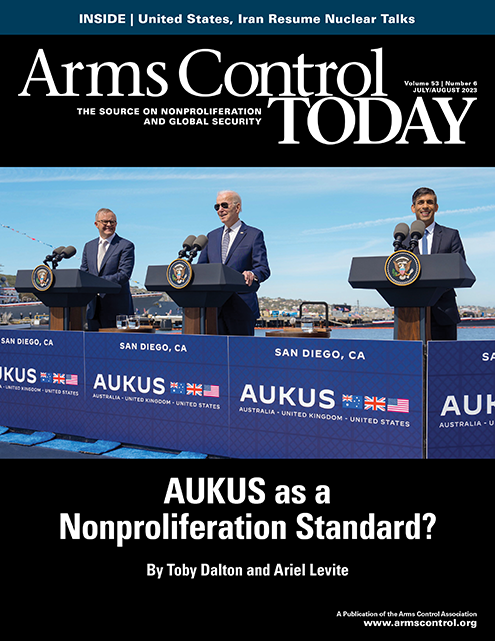

In September 2021, upon concluding the initial agreement to supply Australia with nuclear-propelled submarines, the three AUKUS parties explicitly pledged to subject the accord to the highest nonproliferation standards.

Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States stated that “Australia is committed to adhering to the highest standards for safeguards, transparency, verification, and accountancy measures to ensure the non-proliferation, safety, and security of nuclear material and technology…[and] to fulfilling all of its obligations as a non-nuclear weapons state, including with the International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA].” They also asserted, “Our three nations are deeply committed to upholding our leadership on global non-proliferation.”1

Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States stated that “Australia is committed to adhering to the highest standards for safeguards, transparency, verification, and accountancy measures to ensure the non-proliferation, safety, and security of nuclear material and technology…[and] to fulfilling all of its obligations as a non-nuclear weapons state, including with the International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA].” They also asserted, “Our three nations are deeply committed to upholding our leadership on global non-proliferation.”1

Eighteen months on, however, the official release in March 2023 of the AUKUS implementation plan makes clear that the arrangements do not meet the high nonproliferation bar that the parties have set for themselves.2 Recognizing the serious concerns raised by the unprecedented transfer of conventionally armed nuclear-powered submarines, a new class referenced as the SSN AUKUS, from two nuclear-weapon states to a non-nuclear-weapon state, the three parties have gone some distance to reassure the international community about their intentions.3 The practical implementation arrangements, which include the transfer of sealed power units, would make it exceedingly difficult for Australia to divert without detection the highly enriched uranium (HEU) fuel during the operational lifetime of the submarines. Furthermore, statements by IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi affirm the progress made in the extensive discussions between the three parties and the IAEA on special safeguards arrangements. They indicate that the agency is now confident it could ascertain that the nuclear fuel has not been diverted, notwithstanding the severe national security restrictions imposed by the AUKUS parties on the agency’s access to the fuel and the submarines.4

Welcome as these positive steps are, they nevertheless fall short of the stated aspiration to achieve the highest standards for nonproliferation. Even the AUKUS parties’ explanation that cost and convenience were the driving rationale for choosing HEU fuel over the far less sensitive and precedential option of low-enriched uranium fuel, for example, shows that they put other considerations well ahead of nonproliferation.5

There is still time and opportunity for Australia, the UK, and the United States to remedy outstanding concerns and come closer to establishing a stronger nonproliferation baseline for such endeavors and for the international community to develop a broader framework for building reassurance around more sensitive applications of fissile material and related activities of proliferation concern.

Proliferation Concerns

Two serious, interrelated proliferation concerns pertaining to the submarine transfer remain to be tackled. First, the nonproliferation commitments that Australia has made thus far in the AUKUS context reflect narrow, inherently reversible, unilateral or trilateral policy choices. This is disconcerting because a future Australian government, perhaps in consultation with its partners, may opt to walk them back with the same ease and speed that the previous government reversed the earlier contract to acquire French diesel electric submarines, opting for UK/U.S. nuclear-powered ones instead.

One important element pertains to the announced Australian commitment “not (to) enrich uranium or reprocess spent fuel as part of this program.”6 This pledge does not preclude Australia from developing a parallel, indigenous nuclear fuel cycle unconnected to AUKUS activities. Although the Australian government has given no indication of a desire to do that, the policy option remains. Notably, Australia has extensive prior experience in developing uranium-enrichment technology and at one time had a strong interest in acquiring nuclear weapons.7

As a matter of policy involving the UK and the United States, Australia also could decide to convert the AUKUS submarines to carry U.S. nuclear weapons under a dual-key arrangement similar to that by which the United States “shares” nuclear weapons with its NATO allies. This would require the United States to develop and deploy new nuclear-armed cruise missiles for sea-based platforms, a capability that is already under active consideration as part of U.S. nuclear modernization plans.8 Such dual-key arrangements are not simply relics of the Cold War because Russia now officially seems determined to set up a similar arrangement with Belarus, claiming merely to be emulating a standard NATO practice.9 With creative lawyering, the AUKUS parties could argue that such a development would not contravene any of their legal obligations under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) or Australia’s obligations not to station nuclear weapons on its territory under the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty, commonly known as the Treaty of Rarotonga, although it is clear that such a move would violate the spirit of these agreements. In any case, the elaborate and tight integration of the Australian navy, through the AUKUS initiative, with the UK and U.S. nuclear navies could make such a reversal easier, faster, and smoother to imagine.

As a matter of policy involving the UK and the United States, Australia also could decide to convert the AUKUS submarines to carry U.S. nuclear weapons under a dual-key arrangement similar to that by which the United States “shares” nuclear weapons with its NATO allies. This would require the United States to develop and deploy new nuclear-armed cruise missiles for sea-based platforms, a capability that is already under active consideration as part of U.S. nuclear modernization plans.8 Such dual-key arrangements are not simply relics of the Cold War because Russia now officially seems determined to set up a similar arrangement with Belarus, claiming merely to be emulating a standard NATO practice.9 With creative lawyering, the AUKUS parties could argue that such a development would not contravene any of their legal obligations under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) or Australia’s obligations not to station nuclear weapons on its territory under the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty, commonly known as the Treaty of Rarotonga, although it is clear that such a move would violate the spirit of these agreements. In any case, the elaborate and tight integration of the Australian navy, through the AUKUS initiative, with the UK and U.S. nuclear navies could make such a reversal easier, faster, and smoother to imagine.

This possibility may seem farfetched today, but in the past, the UK and the United States had collaborations with Australia involving nuclear weapons. Australia pursued several paths to acquire nuclear weapons after 1945.10 Through the late 1960s, Australia and the UK discussed the potential for Canberra to co-develop or procure UK nuclear weapons, part of a broader UK program of engaging in defense and security with its Commonwealth partners.11 Australia also built infrastructure to support an indigenous nuclear weapons program and purchased U.S. F-111 dual-capable fighter bombers.12 Australia still engages in activities that support U.S. extended nuclear deterrence in the Indo-Pacific region.13 The two governments also are planning for the United States to deploy nuclear-capable B-52 bombers to Australia and have not ruled out that those bombers could carry nuclear weapons.14

A second, related concern with the AUKUS arrangement derives from how its nonproliferation assurances are operationalized. In the context of the potential reversibility of stated policies, the weight of demonstrating Australia’s continued abjuration of nuclear weapons falls almost exclusively on the application of its IAEA comprehensive safeguards agreement and additional protocol, while invoking the agreement’s Article 14 exemption from safeguards for so-called nonproscribed military nuclear activity, i.e., military applications not prohibited by the NPT. Granted, these are absolutely necessary first steps. Yet, they do not constitute a sufficient reassurance package given the unprecedented nature of the planned AUKUS nuclear submarine cooperation.

Although the geopolitical rationale behind the AUKUS arrangement is understandable, the parties lamentably have failed to come to terms with its core problems: cooperation between two NPT nuclear-armed states (the UK and the United States) and a non-nuclear-weapon state on the military use of nuclear technology, the transfer of tons of HEU to Australia, and cooperation in developing extensive capabilities for the command, control, and operation of strategic nuclear submarines. Australia also will have to acquire significant expertise in handling spent fuel as part of the plan to dispose of this material within its territory. These perceived risks have triggered international concerns about the AUKUS agreement, however misplaced or contrived some of them may seem.15

All of these issues are exacerbated by the fact that IAEA safeguards were not expressly designed for activities and cooperation of this nature and scope. The security sensitivities inevitably associated with such military applications of nuclear technology and the impracticality of inspecting submarines that are to be deployed stealthily for extended periods at sea will result in substantial restrictions on transparency and IAEA access to the information, facilities, people, and materials involved in the AUKUS cooperation. Such access and information restrictions circumscribe traditional modalities for reassuring the international community about a state’s intent to forswear nuclear weapons and raises questions about the IAEA’s ability to do so for Australia. In this case, Australia’s dependence on highly secretive UK and U.S. naval propulsion and weapons technologies, much of it also supporting UK and U.S. nuclear weapons-carrying submarines, greatly narrows the options available to Australia and its AUKUS partners to persuade others that statements about their non-nuclear strategic intentions are credible.

The stress created by the AUKUS project thus far on the nonproliferation regime broadly defined and on the IAEA safeguards system at its core has far broader implications for the agency’s continued role as the primary international nuclear watchdog. These precedents cause worry that others might engage in similar sensitive activities, whether indigenously or in cooperation with their security partners, that would widen the fissure between the agency’s verification mission and the nonproliferation assurances that it can practically deliver. Indeed, it is plausible that some states, citing the AUKUS precedent, may invoke an exemption to remove fissile material from safeguards and then aim to use that material for nuclear weapons activities. Among such states are those that profess a desire to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines or, in the future, spacecraft and undertake indigenous nuclear fuel production, yet resist ratification of an IAEA additional protocol and have a far less honorable contemporary nonproliferation track record than Australia. What the AUKUS project exposes, therefore, are gaps in the entire regime that cannot be filled readily by traditional nonproliferation norms and mechanisms.

The stress created by the AUKUS project thus far on the nonproliferation regime broadly defined and on the IAEA safeguards system at its core has far broader implications for the agency’s continued role as the primary international nuclear watchdog. These precedents cause worry that others might engage in similar sensitive activities, whether indigenously or in cooperation with their security partners, that would widen the fissure between the agency’s verification mission and the nonproliferation assurances that it can practically deliver. Indeed, it is plausible that some states, citing the AUKUS precedent, may invoke an exemption to remove fissile material from safeguards and then aim to use that material for nuclear weapons activities. Among such states are those that profess a desire to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines or, in the future, spacecraft and undertake indigenous nuclear fuel production, yet resist ratification of an IAEA additional protocol and have a far less honorable contemporary nonproliferation track record than Australia. What the AUKUS project exposes, therefore, are gaps in the entire regime that cannot be filled readily by traditional nonproliferation norms and mechanisms.

Against this background, it becomes easier to appreciate the inadequacy of what the AUKUS parties have done to reassure the world that their unorthodox agreement will not further erode the already stressed nonproliferation regime. How would they have reacted if their adversaries took similar action? How keen would they be to see other aspirants of nuclear-propelled submarines and other non-proscribed nuclear applications stand behind similar policy-oriented and limited reassurances? Would they be critical of the loopholes and shortfalls similar to the ones they have left in the AUKUS arrangement for reasons of national security, geopolitics, cost, and convenience? It is difficult to imagine that Australia, the UK, and the United States would shy away from pointing out the flaws in such initiatives.

The concern that an NPT member state might one day renege on its nonproliferation obligations and seek nuclear weapons through use of assets it acquired legitimately is neither theoretical, new, or unique to Australia. Notably, in January 2023, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol explicitly discussed the possibility that his country could need nuclear weapons to defend against North Korea, notwithstanding Seoul’s robust nonproliferation commitments.16 What makes the Australian case especially disconcerting is that if Canberra were to decide to abandon its nonproliferation commitments, it would be in a far more advanced position to develop a nuclear weapons option thanks to the AUKUS arrangement. Again, accepting that few believe Australia harbors such ambition today, the mere perception that the arrangement could provide a path to this future is provoking regional concerns and creates an unhelpful precedent with which the nonproliferation regime to contend.

Thankfully, the final verdict on the AUKUS agreement is still out. There is time for the AUKUS partners to address outstanding proliferation concerns, reassure others about Australia’s long-term peaceful nuclear intentions, and set a genuinely high nonproliferation bar. The objective should be to establish parameters that would be sufficient to dispel suspicions that the nuclear activities of the AUKUS partners or any other countries that might emulate their agreement might have a weapons orientation. Australia, the UK, and the United States would be well advised to work individually and collectively for such a stronger baseline, but decisions have to be made well before the submarines approach Australian shores. Others, such as Brazil, are also embarking on projects involving nonproscribed military nuclear applications under safeguards exemptions.17

Establishing a Stronger Precedent

To address the two main concerns raised by the AUKUS agreement, Australia first would need to take steps to demonstrate that any reversal of course toward nuclearization would be detectable, difficult, and costly. The more that Australia’s AUKUS nonproliferation commitments are institutionalized through domestic laws and international commitments, the more difficult they become to reverse. Such measures could include passing a law stipulating that Australia would not deploy nuclear weapons on its submarines under any arrangement. It also could establish a mechanism for international monitoring of the new submarines to verify nondeployment of nuclear weapons, a step that could discourage or restrict nuclear sharing arrangements by other states. Australia also could expand in law its commitments not to build national enrichment or reprocessing facilities.

In addition, in conformity with its aspiration to remain a nonproliferation champion and build stronger assurances around the AUKUS arrangement, Australia could pioneer new practices that other states using a safeguards exemption could then be expected to follow. For example, under the additional protocol to its safeguards agreement, Australia could augment its declaration of nuclear material and facilities with a list of dual-use activities that fall under the Nuclear Suppliers Group Part II guidelines pertaining to research, development, and testing of nuclear weapons.18 In Australia’s case, such a “weaponization” declaration would make a material contribution to the IAEA process of reaffirming its so-called broader conclusion that Australia’s nuclear program remains entirely peaceful or at least not directed toward nuclear weapons. This precedent would be exceedingly beneficial for the IAEA if and when it is asked to monitor and inspect programs involving weapons-usable fissile materials in other non-nuclear-weapon states.

Individually, none of these steps are irreversible, but implementing them would still make it a little more difficult, through political friction and the potential for international consequences, to reverse course. Collectively, they would greatly reassure the international community and therefore set a stronger precedent. Because the AUKUS agreement is such a special case, it demands special arrangements to go further than the parties have thus far committed to go. Actions of the nature suggested here would lend considerable credibility to Australia’s claim to be a nonproliferation and nuclear responsibility champion.

The UK and the United States also should consider complementary steps that would help achieve the high nonproliferation standard they promised. First, although the safeguards measures that Australia will undertake with the IAEA to monitor the HEU transferred for submarine fuel will create reasonable assurances that this material would not be diverted for use in nuclear weapons in the immediate future, there is the long-term matter of what happens to that fuel once the submarine has reached the end of its operational life. Ideally, this irradiated HEU would not remain in Australia, but would be transferred back to the UK or the United States for disposition so that Australia would not possess or store any spent fuel on its territory. In parallel to existing programs to take back irradiated HEU from research reactors around the world and to its domestic program to manage its own spent submarine fuel, it is reasonable that the United States should create a legal avenue to enable the return of Australian submarine fuel.19 In the unwelcome but likely event that at least some spent fuel remains in Australia, Canberra should anchor its pledge not to undertake any spent fuel reprocessing of any type on its territory in a law that requires an especially large parliamentary majority to overturn. Together, these acts would create a much higher standard with respect to the disposition of submarine spent fuel.

As international reaction to the AUKUS initiative demonstrates, there is palpable concern that the AUKUS partners might someday choose to deploy U.S. or, secondarily, UK nuclear weapons on Australian submarines. To address this criticism and reassure the international community as to the defensive purpose of the initiative, the partners should join Australia in making a nuclear weapons nondeployment commitment and in establishing an inspection protocol, most reasonably with the IAEA, to ascertain that no nuclear weapons are on board. This protocol could entail the use of information barriers or other black-box techniques that would permit confirmation that nuclear material is not present in the vertical launch payload section of the submarine.

Beyond the AUKUS Arrangement

Looking ahead, the international community faces the prospect of further growth in novel and nonproscribed nuclear military applications and, with it, pressure on the IAEA and its traditional safeguards measures to sustain nonproliferation assurances. These applications include not only naval propulsion, but also micro- and mobile reactors deployed on military bases or used in space or other nonterrestrial activities, for example. Such developments occur against a sobering backdrop of a broader and growing global interest in nuclear enrichment technology and related indigenous activities, as well as in the accumulation of higher enrichment levels for and quantities of uranium-235.20 On the face of it, none of these activities is illegitimate, precluded, restricted, or even subject to special scrutiny under any international regime currently in place, given that the long-discussed fissile material cutoff treaty has never materialized. Unfortunately, geopolitical rivalries do not inspire much hope for breaking the deadlock on negotiating new arms control and nonproliferation treaties or conventions that could generate new or additional legally binding approaches to reassurance in cases involving these proliferation sensitive activities.

Thus, it is imperative for the international community to look for alternative means to supplement traditional legal nonproliferation and arms control regimes. Namely, it will be necessary to develop voluntary, cooperative, complementary measures. Such measures should aim to provide reassurance that nuclear activities involving safeguards exemptions for military applications, especially classified programs such as naval propulsion or other atypical uses of nuclear materials, are not conducted in support of a weapons program, while giving timely and credible early warning of any potentially alarming changes. For example, states undertaking nonproscribed military nuclear activity, in addition to implementing a comprehensive safeguards agreement and an additional protocol, should be expected to provide additional forms and means of transparency to the IAEA, such as wide-area environmental sampling, declarations of their other technical activities that could contribute to nuclear weapons design,and regulated access to military facilities where such activities occur. These states also should commit voluntarily to address all pertinent IAEA queries, even when they go beyond nominal safeguards obligations. Expanding the voluntary exchange of information around best practices in all aspects of nuclear operations—safety and security, as well as safeguards—would be a useful and expedient means of building confidence at a time of growing geopolitical tension.

To secure broad buy-in, new arrangements must meet significant criteria. First, they should be constructed carefully so as not to stand in the way of activities that might be sensitive yet legitimate, such as naval propulsion projects such as the AUKUS arrangement. Second, as it is unlikely that new binding obligations can be negotiated, it would be more expedient to frame new reassurance measures as expectations for responsible nonproliferation conduct. Third, they must be directed at all parties involved in proliferation-sensitive activities: exporters, importers, governments, and enterprises alike, including when the activity is purely indigenous. Such expectations should also be nondiscriminatory in nature, meaning they would apply equally to all non-nuclear-weapon states, not just those favored by one major power or another. Finally and perhaps most critically, it is useful to consider how to meaningfully incentivize responsible behavior with sensitive nuclear materials and technologies.

When viewed in this light, many of these proposed AUKUS-related reassurance actions could thus also pioneer a broader reassurance regime, should a global increase in the military uses of nuclear technology indeed materialize. Such actions might not quell the criticism of those opposed to the AUKUS arrangement on geopolitical grounds, but it could assuage genuine, although perhaps exaggerated concerns and provide a road map for innovating nonproliferation regimes that risk failing to keep pace with developments. In doing so, Australia, the UK, and the United States could credibly claim to be setting the highest standards for such activities going forward.

ENDNOTES

1. The White House, “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” September 15, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/15/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus/.

2. The White House, “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” March 12, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/13/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-2/.

3. Frank N. von Hippel, “The Australia-UK-U.S. Submarine Deal: Mitigating Proliferation Concerns,” Arms Control Today, November 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-11/features/australia-uk-us-submarine-deal-mitigating-proliferation-concerns; Laura Rockwood, “The Australia-UK-U.S. Submarine Deal: Submarines and Safeguards,” Arms Control Today, December 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-12/features/australia-uk-us-submarine-deal-submarines-safeguards.

4. International Atomic Energy Agency, “Director General Statement in Relation to AUKUS Announcement,” March 14, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/director-general-statement-in-relation-to-aukus-announcement.

5. U.S. officials, briefing for nongovernmental experts via zoom, Washington, March 10, 2023.

6. The White House, “Trilateral Australia-UK-US Partnership on Nuclear-Powered Submarines,” March 13, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/13/fact-sheet-trilateral-australia-uk-us-partnership-on-nuclear-powered-submarines/.

7. Mary Beth Nikitin and Bruce Vaughn, “U.S.-Australia Civilian Nuclear Cooperation: Issues for Congress,” CRS Report for Congress, R41312, January 18, 2011; Jim Walsh, “Surprise Down Under: The Secret History of Australia’s Nuclear Ambitions,” The Nonproliferation Review, Fall 1997, https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/walsh51.pdf.

8. John Gower, “AUKUS After San Diego: The Real Challenges and Nuclear Risks,” APLN Policy Brief, March 2023, https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PB-99-Gower.pdf.

9. “Russia's Actions in Ukraine and Belarus,” The New York Times, March 26, 2023.

10. Wayne Reynolds, Australia’s Bid for the Atomic Bomb (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2000); Christine M. Leah and Crispin Rovere, “Chasing Mirages: Australia and the U.S. Nuclear Umbrella in the Asia-Pacific,” NPIHP Issue Brief, No. 1 (March 2013).

11. Reynolds, Australia’s Bid for the Atomic Bomb.

12. Walsh, “Surprise Down Under.”

13. Ashley Townshend and Brendan Thomas-Noone, “There's a Part of the US-Australia Alliance We Rarely Talk About: Nuclear Weapons," United States Studies Centre, February 27, 2019, https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/theres-a-part-of-the-us-australia-alliance-we-rarely-talk-about-nuclear-weapons.

14. Andrew Greene, "Defence Won't Confirm If US Bombers Carry Nuclear Weapons," ABC News Australia, February 15, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-02-15/defence-wont-confirm-if-us-bombers-carry-nuclear-weapons/101978596.

15. 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Nuclear Naval Propulsion: Working Paper Submitted by Indonesia,” NPT/CONF.2020/WP.67, July 25, 2022.

16. Choe Sang-Hun, “In a First, South Korea Declares Nuclear Weapons a Policy Option,”

The New York Times, January 12, 2023.

17. Francois Murphy, “Brazil Initiates Talks With IAEA on Fuel for Planned Nuclear Submarine,” Reuters, June 6, 2022.

18. Nuclear Suppliers Group, “Guidelines for Transfers of Nuclear-Related Dual-Use Equipment, Materials, Software, and Related Technology,” INFCIRC/254/Rev.12/Part 2, n.d.

19. U.S. congressional authorization would be required for the return of spent fuel from an SSN AUKUS submarine to the United States. See James M. Acton, “How to the Solve the AUKUS Nuclear Submarine Deal’s Spent Fuel Problem,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 13, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/06/13/how-to-solve-aukus-nuclear-submarine-deal-s-nuclear-fuel-problem-pub-89958.

20. See Edward Wong, Vivian Nereim, and Kate Kelly, “Inside Saudi Arabia’s Global Push for Nuclear Power,” The New York Times, April 1, 2023.

Toby Dalton is a senior fellow and co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP). Ariel Levite is a nonresident senior fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program and the Technology and International Affairs Program at CEIP.

The last remaining treaty limiting the massive U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals is in jeopardy and will expire in less than 950 days. There are no talks underway on what might replace it. Meanwhile, China is quickly expanding its relatively smaller nuclear arsenal, refusing U.S. overtures for a bilateral nuclear dialogue, and resisting calls to halt fissile material production for nuclear weapons.

The last remaining treaty limiting the massive U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals is in jeopardy and will expire in less than 950 days. There are no talks underway on what might replace it. Meanwhile, China is quickly expanding its relatively smaller nuclear arsenal, refusing U.S. overtures for a bilateral nuclear dialogue, and resisting calls to halt fissile material production for nuclear weapons. Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States stated that “Australia is committed to adhering to the highest standards for safeguards, transparency, verification, and accountancy measures to ensure the non-proliferation, safety, and security of nuclear material and technology…[and] to fulfilling all of its obligations as a non-nuclear weapons state, including with the International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA].” They also asserted, “Our three nations are deeply committed to upholding our leadership on global non-proliferation.”

Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States stated that “Australia is committed to adhering to the highest standards for safeguards, transparency, verification, and accountancy measures to ensure the non-proliferation, safety, and security of nuclear material and technology…[and] to fulfilling all of its obligations as a non-nuclear weapons state, including with the International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA].” They also asserted, “Our three nations are deeply committed to upholding our leadership on global non-proliferation.” As a matter of policy involving the UK and the United States, Australia also could decide to convert the AUKUS submarines to carry U.S. nuclear weapons under a dual-key arrangement similar to that by which the United States “shares” nuclear weapons with its NATO allies. This would require the United States to develop and deploy new nuclear-armed cruise missiles for sea-based platforms, a capability that is already under active consideration as part of U.S. nuclear modernization plans.

As a matter of policy involving the UK and the United States, Australia also could decide to convert the AUKUS submarines to carry U.S. nuclear weapons under a dual-key arrangement similar to that by which the United States “shares” nuclear weapons with its NATO allies. This would require the United States to develop and deploy new nuclear-armed cruise missiles for sea-based platforms, a capability that is already under active consideration as part of U.S. nuclear modernization plans. The stress created by the AUKUS project thus far on the nonproliferation regime broadly defined and on the IAEA safeguards system at its core has far broader implications for the agency’s continued role as the primary international nuclear watchdog. These precedents cause worry that others might engage in similar sensitive activities, whether indigenously or in cooperation with their security partners, that would widen the fissure between the agency’s verification mission and the nonproliferation assurances that it can practically deliver. Indeed, it is plausible that some states, citing the AUKUS precedent, may invoke an exemption to remove fissile material from safeguards and then aim to use that material for nuclear weapons activities. Among such states are those that profess a desire to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines or, in the future, spacecraft and undertake indigenous nuclear fuel production, yet resist ratification of an IAEA additional protocol and have a far less honorable contemporary nonproliferation track record than Australia. What the AUKUS project exposes, therefore, are gaps in the entire regime that cannot be filled readily by traditional nonproliferation norms and mechanisms.

The stress created by the AUKUS project thus far on the nonproliferation regime broadly defined and on the IAEA safeguards system at its core has far broader implications for the agency’s continued role as the primary international nuclear watchdog. These precedents cause worry that others might engage in similar sensitive activities, whether indigenously or in cooperation with their security partners, that would widen the fissure between the agency’s verification mission and the nonproliferation assurances that it can practically deliver. Indeed, it is plausible that some states, citing the AUKUS precedent, may invoke an exemption to remove fissile material from safeguards and then aim to use that material for nuclear weapons activities. Among such states are those that profess a desire to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines or, in the future, spacecraft and undertake indigenous nuclear fuel production, yet resist ratification of an IAEA additional protocol and have a far less honorable contemporary nonproliferation track record than Australia. What the AUKUS project exposes, therefore, are gaps in the entire regime that cannot be filled readily by traditional nonproliferation norms and mechanisms. As in the cases of China and Japan, this strategic landscape has inspired changes to South Korea’s national security strategy. The administration of President Yoon Suk Yeol has adopted a defense-driven nuclear nonproliferation policy that centers on deterrence as its principal approach to risk reduction and arms control. South Korea is seeking to address the increasing threats of aggression, inadvertent escalation, and nuclear use by signaling advances in its conventional capabilities and its military cooperation with the United States. While continuing to forgo nuclear armament, South Korea is aiming to deny North Korea gaining an advantage from its expanding nuclear weapons arsenal and to shape conditions that are more conducive to a productive dialogue on arms control.

As in the cases of China and Japan, this strategic landscape has inspired changes to South Korea’s national security strategy. The administration of President Yoon Suk Yeol has adopted a defense-driven nuclear nonproliferation policy that centers on deterrence as its principal approach to risk reduction and arms control. South Korea is seeking to address the increasing threats of aggression, inadvertent escalation, and nuclear use by signaling advances in its conventional capabilities and its military cooperation with the United States. While continuing to forgo nuclear armament, South Korea is aiming to deny North Korea gaining an advantage from its expanding nuclear weapons arsenal and to shape conditions that are more conducive to a productive dialogue on arms control. South Korea’s status as a U.S. treaty ally inspires greater confidence in the U.S. security commitment than Ukraine enjoyed and in Washington’s readiness to back this guarantee with the full range of its capabilities, including nuclear weapons. Seoul appreciates that the forward deployment of U.S. forces to South Korea, as well as broad economic cooperation and the depth of its people-to-people ties with the United States, underwrites the U.S. commitment to support South Korea’s defense. Seoul also recognizes, however, the inherent uncertainty of future U.S. political leadership and decision-making. It understands that when faced with resource constraints, the primary strategic priority of the United States is competition with China.

South Korea’s status as a U.S. treaty ally inspires greater confidence in the U.S. security commitment than Ukraine enjoyed and in Washington’s readiness to back this guarantee with the full range of its capabilities, including nuclear weapons. Seoul appreciates that the forward deployment of U.S. forces to South Korea, as well as broad economic cooperation and the depth of its people-to-people ties with the United States, underwrites the U.S. commitment to support South Korea’s defense. Seoul also recognizes, however, the inherent uncertainty of future U.S. political leadership and decision-making. It understands that when faced with resource constraints, the primary strategic priority of the United States is competition with China. Finally, even if the United States has the political will to deliver military support to South Korea, there is growing concern about its capacity to do so in the near term due to defense supply chain challenges. As a result of the Russian war in Ukraine, diminishing stockpiles have required the United States to “borrow” 500,000 artillery shells from South Korea.

Finally, even if the United States has the political will to deliver military support to South Korea, there is growing concern about its capacity to do so in the near term due to defense supply chain challenges. As a result of the Russian war in Ukraine, diminishing stockpiles have required the United States to “borrow” 500,000 artillery shells from South Korea. The government of President Moon Jae-in pursued dialogue with North Korea as a means to establish inter-Korean peace and denuclearize the peninsula. It balanced engagement with defense efforts, implementing a vision of “peace through strength” that invested heavily in bolstering South Korea’s advanced conventional capabilities. It also worked to make its forces and its alliance with the United States appear less threatening to North Korea. It muted deterrence signaling, such as shows of force. It reduced the scope and scale of combined theater-level exercises with the United States, relabeled these efforts to emphasize a focus on defensive training, and ceased the work of the Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultative Group, which advanced policy coordination to counter North Korea’s nuclear threat. Through engagement, the Moon administration aspired to demonstrate its reconciliation-focused agenda and to reduce the risk of conflict by lowering tensions. It sought to facilitate dialogue between North Korea and the United States aimed at détente and denuclearization. The Moon government also forged a Comprehensive Military Agreement with North Korea, through which the two countries adopted behavioral arms control and confidence-building measures.

The government of President Moon Jae-in pursued dialogue with North Korea as a means to establish inter-Korean peace and denuclearize the peninsula. It balanced engagement with defense efforts, implementing a vision of “peace through strength” that invested heavily in bolstering South Korea’s advanced conventional capabilities. It also worked to make its forces and its alliance with the United States appear less threatening to North Korea. It muted deterrence signaling, such as shows of force. It reduced the scope and scale of combined theater-level exercises with the United States, relabeled these efforts to emphasize a focus on defensive training, and ceased the work of the Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultative Group, which advanced policy coordination to counter North Korea’s nuclear threat. Through engagement, the Moon administration aspired to demonstrate its reconciliation-focused agenda and to reduce the risk of conflict by lowering tensions. It sought to facilitate dialogue between North Korea and the United States aimed at détente and denuclearization. The Moon government also forged a Comprehensive Military Agreement with North Korea, through which the two countries adopted behavioral arms control and confidence-building measures. A different path to achieve this goal is possible. First and foremost, it would be timely and important to agree on a verifiable, broadly supported definition of what is not a nuclear weapon. This is by no means a trivial task, but one in which nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states actively could engage, even today. Verification of several possible future arms control measures can be supported by such a negative definition, including the removal of tactical nuclear weapons from entire geographical regions, verification procedures relevant for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), and verified limits on total stockpiles.

A different path to achieve this goal is possible. First and foremost, it would be timely and important to agree on a verifiable, broadly supported definition of what is not a nuclear weapon. This is by no means a trivial task, but one in which nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states actively could engage, even today. Verification of several possible future arms control measures can be supported by such a negative definition, including the removal of tactical nuclear weapons from entire geographical regions, verification procedures relevant for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), and verified limits on total stockpiles. In the 1980s, there were proposals to reintroduce such “clip-in” or “insertable” warheads into the U.S. stockpile, perhaps for lower-yield tactical nuclear weapons, a prospect considered an “arms control nightmare” by some analysts.

In the 1980s, there were proposals to reintroduce such “clip-in” or “insertable” warheads into the U.S. stockpile, perhaps for lower-yield tactical nuclear weapons, a prospect considered an “arms control nightmare” by some analysts.

And before I jump into this, let me just step back and say that “without preconditions” does not mean “without accountability.” We’ll still hold nuclear powers accountable for reckless behavior, and we’ll still hold our adversaries and competitors responsible for upholding nuclear agreements. For example, the United States will continue to notify Russia in advance of ballistic missile launches and major strategic exercises, in line with preexisting nuclear agreements.

And before I jump into this, let me just step back and say that “without preconditions” does not mean “without accountability.” We’ll still hold nuclear powers accountable for reckless behavior, and we’ll still hold our adversaries and competitors responsible for upholding nuclear agreements. For example, the United States will continue to notify Russia in advance of ballistic missile launches and major strategic exercises, in line with preexisting nuclear agreements.

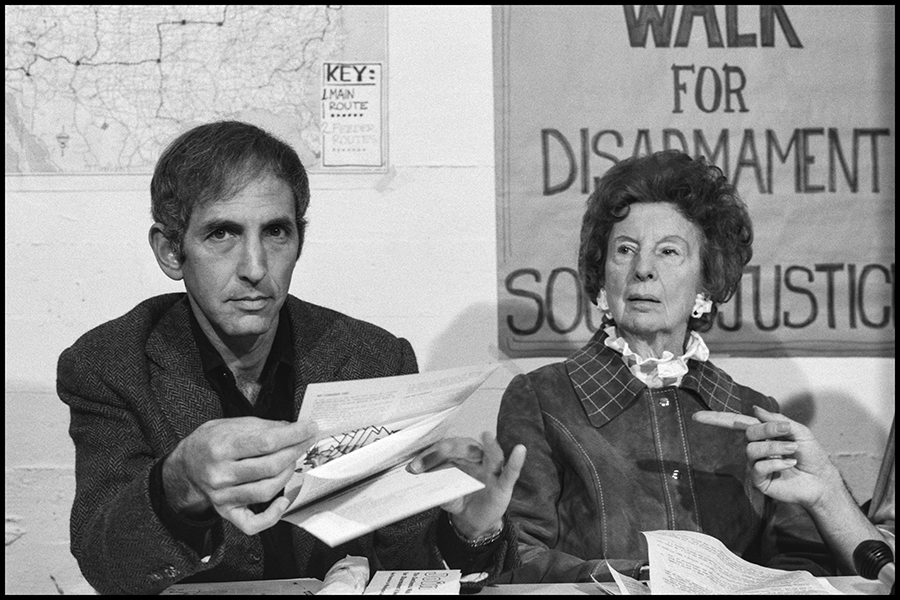

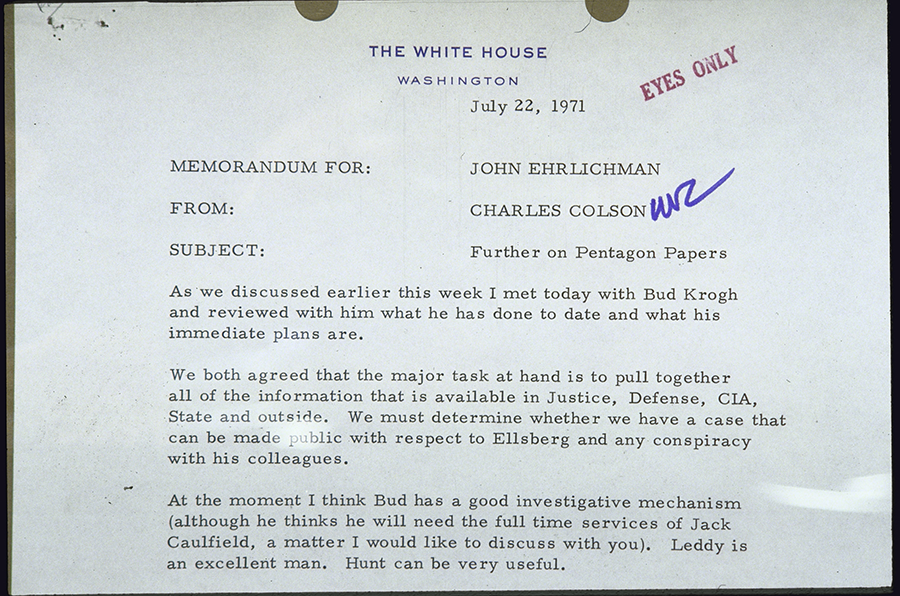

Dan Ellsberg lived an original life on the frontlines of academia, war, and international political debate. If his life were a movie, the title would be “Walking Point.” The trailer would include Ellsberg staffing not one, but two, U.S. departments—Defense and State (Paul Nitze and Walt Rostow, respectively)—in the Kennedy White House’s secret deliberations to manage the Cuban missile crisis; two years embedded with combat units in Vietnam, often walking point; the secret copying and leaking of the Pentagon Papers; the moves by President Richard Nixon and his “plumbers” to discredit and silence him by any means necessary, including violence; Nixon’s subsequent resignation; and decades of activism, protest, and arrest trying to end nuclear arms racing and threat-making. Yet, these dramatic snippets—each one a lifetime of achievement for most of us—would not do Ellsberg justice.

Dan Ellsberg lived an original life on the frontlines of academia, war, and international political debate. If his life were a movie, the title would be “Walking Point.” The trailer would include Ellsberg staffing not one, but two, U.S. departments—Defense and State (Paul Nitze and Walt Rostow, respectively)—in the Kennedy White House’s secret deliberations to manage the Cuban missile crisis; two years embedded with combat units in Vietnam, often walking point; the secret copying and leaking of the Pentagon Papers; the moves by President Richard Nixon and his “plumbers” to discredit and silence him by any means necessary, including violence; Nixon’s subsequent resignation; and decades of activism, protest, and arrest trying to end nuclear arms racing and threat-making. Yet, these dramatic snippets—each one a lifetime of achievement for most of us—would not do Ellsberg justice. In conversation, he was charming. I first met him in June 1981, at a Student Pugwash Conference at Yale University. Ellsberg was an informal after-dinner speaker. The setting was one of those large homes that wealthy universities buy and convert into offices for quirky new interdisciplinary programs. Ellsberg sat in a living room-like chair; a few score of young people sat on the floor and chairs around him. I was 22 and had never met someone so notorious, the man who broke the rules and brought down a president, the anti-war, anti-nuke publicity hound. What I remember were his blue-grey eyes and how his extremely powerful intelligence and passion burned behind them. At the time, I was not informed enough to judge his message, but I was awed by his mastery and his energy.

In conversation, he was charming. I first met him in June 1981, at a Student Pugwash Conference at Yale University. Ellsberg was an informal after-dinner speaker. The setting was one of those large homes that wealthy universities buy and convert into offices for quirky new interdisciplinary programs. Ellsberg sat in a living room-like chair; a few score of young people sat on the floor and chairs around him. I was 22 and had never met someone so notorious, the man who broke the rules and brought down a president, the anti-war, anti-nuke publicity hound. What I remember were his blue-grey eyes and how his extremely powerful intelligence and passion burned behind them. At the time, I was not informed enough to judge his message, but I was awed by his mastery and his energy. One weekend in December 1965, Ellsberg and his friend Vann decided to drive north through the kind of dangerous territory that all other Americans flew over. As Neil Sheehan recounted in his biography of Vann, A Bright Shining Lie, the two men wanted to explore conditions on the ground. Vann drove with one hand, holding in the other an M-16 automatic rifle perched on the door facing the rain forest. When the jungle encroached in a perfect setup for ambush, Ellsberg, the skinny Harvard doctorate, “glanced down at this side to be sure a grenade was handy and lifted the carbine he had been cradling in his lap so that he could immediately open fire out the window.”

One weekend in December 1965, Ellsberg and his friend Vann decided to drive north through the kind of dangerous territory that all other Americans flew over. As Neil Sheehan recounted in his biography of Vann, A Bright Shining Lie, the two men wanted to explore conditions on the ground. Vann drove with one hand, holding in the other an M-16 automatic rifle perched on the door facing the rain forest. When the jungle encroached in a perfect setup for ambush, Ellsberg, the skinny Harvard doctorate, “glanced down at this side to be sure a grenade was handy and lifted the carbine he had been cradling in his lap so that he could immediately open fire out the window.” Ellsberg’s relationship with secrets was intense and complicated. He was fascinated, captivated, and troubled by them. In 1965, when Ellsberg wanted to leave his influential job advising John McNaughton, assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, and go to Vietnam, McNaughton did not try to dissuade him. As Sheehan recounts, McNaughton “was becoming skittish about Ellsberg. A need to boast about what he knew made Ellsberg somewhat indiscreet under normal circumstances.”

Ellsberg’s relationship with secrets was intense and complicated. He was fascinated, captivated, and troubled by them. In 1965, when Ellsberg wanted to leave his influential job advising John McNaughton, assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, and go to Vietnam, McNaughton did not try to dissuade him. As Sheehan recounts, McNaughton “was becoming skittish about Ellsberg. A need to boast about what he knew made Ellsberg somewhat indiscreet under normal circumstances.” Such steps could reduce the likelihood of conflict because Iran’s current nuclear trajectory is increasing the risk that the United States or Israel will determine that military action is necessary to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

Such steps could reduce the likelihood of conflict because Iran’s current nuclear trajectory is increasing the risk that the United States or Israel will determine that military action is necessary to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Although NATO members have pledged to continue supporting Ukraine, they differ on its eventual accession to the alliance. “This is not a situation where the entire alliance has agreed language for how to describe Ukraine’s membership aspirations, and there’s one or two countries that stand outside of that group in opposition,” Julianne Smith, U.S. ambassador to NATO, said June 14 during a U.S. State Department briefing from Brussels.

Although NATO members have pledged to continue supporting Ukraine, they differ on its eventual accession to the alliance. “This is not a situation where the entire alliance has agreed language for how to describe Ukraine’s membership aspirations, and there’s one or two countries that stand outside of that group in opposition,” Julianne Smith, U.S. ambassador to NATO, said June 14 during a U.S. State Department briefing from Brussels. U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan outlined the proposal in a speech to the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting in Washington on June 2. “Rather than waiting to resolve all of our bilateral differences, the United States is ready to engage Russia now to manage nuclear risks and develop a post-2026 arms control framework” to follow the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) after its expiration in 2026, he said.

U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan outlined the proposal in a speech to the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting in Washington on June 2. “Rather than waiting to resolve all of our bilateral differences, the United States is ready to engage Russia now to manage nuclear risks and develop a post-2026 arms control framework” to follow the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) after its expiration in 2026, he said.