June 2017

By John Burroughs

The outlines of a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading to their total elimination, emerged in late March during the first week of negotiations among diplomats representing about 130 governments. During a second session, to take place from June 15 to July 7 at the United Nations, a text will be negotiated, based on the May 22 draft by the president of the negotiating conference, Ambassador Elayne Whyte Gómez of Costa Rica. She aims for conference approval of a text by the end of that session.

The envisaged treaty would be a relatively simple one, prohibiting the development, stockpiling, and use of nuclear weapons but not containing detailed provisions relating to the verified dismantlement of nuclear arsenals and to governance of a world free of nuclear weapons. The basic intent is to codify the norms of nonuse and nonpossession of nuclear weapons in light of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear explosions and to contribute to the eventual achievement of the global abolition of the weapons. Issues related to elimination of nuclear weapons will largely be left to later negotiations, within or outside the treaty framework, because none of the states possessing nuclear arsenals are participating nor are almost all states in nuclear alliances with the United States.

The envisaged treaty would be a relatively simple one, prohibiting the development, stockpiling, and use of nuclear weapons but not containing detailed provisions relating to the verified dismantlement of nuclear arsenals and to governance of a world free of nuclear weapons. The basic intent is to codify the norms of nonuse and nonpossession of nuclear weapons in light of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear explosions and to contribute to the eventual achievement of the global abolition of the weapons. Issues related to elimination of nuclear weapons will largely be left to later negotiations, within or outside the treaty framework, because none of the states possessing nuclear arsenals are participating nor are almost all states in nuclear alliances with the United States.

The negotiations grew out of the initiative on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons use, particularly the governmental conferences in Oslo; Nayarit, Mexico; and Vienna in 2013 and 2014. During the 2016 UN open-ended working group on nuclear disarmament, deliberations led to adoption of the strategy of seeking a prohibition or ban treaty and identified many of its elements.

The UN General Assembly in December 2016 adopted a resolution1 to convene the negotiating conference, put forward by lead sponsors Austria, Brazil, Ireland, Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa. Proponents have emphasized that, like regional nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties, the prohibition treaty will be complementary to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Indeed, they observe, it will partially fulfill Article VI, which requires NPT states-parties to "pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to … nuclear disarmament."

During the first week, most governments endorsed the negotiation of a treaty focused on prohibition. The positions of countries such as Algeria and Cuba, although accepting the notion of a prohibition treaty, nonetheless in the sweep of their recommendations reflect the long-standing Non-Aligned Movement support for a convention addressing all aspects of nuclear disarmament.2 Malaysia noted that it has been a champion of that approach, having put forward a model convention with Costa Rica. Many countries continue to foresee a future comprehensive agreement on nuclear disarmament following a prohibition treaty. The resolution convening the negotiations generally recognizes in its preamble that "additional measures, both practical and legally binding, for the irreversible, verifiable and transparent destruction of nuclear weapons would be needed in order to achieve and maintain a world without nuclear weapons."3

Differences concerning scope remain even among strong proponents of the nuclear ban treaty process. In Mexico’s view, negotiators should focus on setting broad prohibitions on possession, acquisition, stockpiling, use, development, transfer, stationing and deployment, and assistance with prohibited acts. They should not venture into complex, time-consuming issues, including those, such as a prohibition on testing, potentially affecting how other legal instruments are interpreted and applied. Alexander Marschik, Austrian vice minister for foreign affairs, stated, "There is a risk that we want to achieve too much…. Please, stay together behind this one, narrow, clear objective: a legal prohibition of nuclear weapons." Reflecting this view, Austria proposed a set of prohibitions restricted to use, development, production, stockpiling, transfer, and assistance with prohibited acts.

On the other hand, South Africa stated that although "the instrument would clearly be more limited than a Nuclear Weapons Convention," it does not "support the idea of turning a simple political declaration into a legally-binding instrument. [It] is unlikely to be taken seriously by those who may choose to remain outside…. More comprehensive prohibitions would therefore be preferred in the form of an unambiguous legal text." New Zealand stated, "We must not, by the omission of any key nuclear weapon development-related activities, seem to create any ambiguity or leave open any possible gap in its coverage."

Variety of Issues

As these positions indicate, drafting the treaty is not as straightforward as might first appear. The participants are non-nuclear-weapon state-parties to the NPT, which bars their acquisition of nuclear weapons, and most are also parties to nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties. In certain respects, however, the prohibition treaty likely will go beyond the NPT and the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties by imposing additional obligations.

Moreover, the treaty will generally help establish a template for future nuclear disarmament, as well as provide for possible accession of nuclear-armed states after they have disarmed or subject to a time-bound disarmament obligation. Most negotiators also want to make it possible for states in alliances with nuclear-armed states to join the treaty, provided that the allied states end reliance on nuclear weapons. For these and other reasons, a variety of difficult issues will have to be resolved.

Moreover, the treaty will generally help establish a template for future nuclear disarmament, as well as provide for possible accession of nuclear-armed states after they have disarmed or subject to a time-bound disarmament obligation. Most negotiators also want to make it possible for states in alliances with nuclear-armed states to join the treaty, provided that the allied states end reliance on nuclear weapons. For these and other reasons, a variety of difficult issues will have to be resolved.

This survey of key issues facing negotiators at the second session addresses prohibitions relating to development and manufacture, possession and stockpiling, transit, and use and threat of use; a prohibition on assistance; implementation of the treaty and positive obligations, for example, relating to victims of use and testing of nuclear weapons; institutional issues, including how nuclear-armed states could join the treaty, and final clauses; and the framing of the treaty in its preamble.4

Development and Manufacture

During the first week of negotiations, there was wide support for including a prohibition on development of nuclear weapons as well as their manufacture and/or production. This would provide clarity as compared with the NPT, which only expressly prohibits "manufacture." It would also address a gap in the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties, not all of which contain a prohibition on development.5

Exactly what activities constitute development? It clearly includes engineering leading to production, but does it include research and design? The term "research" could embrace, for example, simply gaining knowledge about nuclear weapons. Accordingly, there may be reluctance to consider it as an activity of development or to prohibit it separately, as it is in two nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties.6 The term "design," however, is intrinsically related to creation of a warhead and is a term in common use in the nuclear sphere, although it has not been specifically banned in existing treaties prohibiting and eliminating biological weapons, chemical weapons, landmines and cluster munitions.

A related subject of discussion was whether to include a separate prohibition on nuclear explosive testing. Austria and Mexico contended that testing would be covered by a development ban. Further, they said, a separate testing prohibition would raise issues of consistency with the nuclear Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Brazil, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, and other states favored a prohibition. During a conference discussion with experts, physicist Zia Mian, co-director of the Program on Science and Global Security at Princeton University, explained that not all testing is for development; it may be conducted, for example, to confirm the reliability of a weapon. A complication is that a whole range of activities—computer simulation, hydrodynamic and laser fusion experiments, subcritical explosions—may be considered "testing," and Brazil, South Africa, and other states expressed the desire explicitly to prohibit such activities.

The above issues could be resolved by including definitions of "development" and other key terms. Yet, some states are opposed, observing that it would delay negotiations and that the NPT does not provide definitions. The issues probably also could be resolved in drafting the prohibitions. A prohibition of testing could be made identical with the CTBT prohibition.7 Also, the ban treaty almost certainly will include a provision stating that its terms do not limit or detract from obligations under the CTBT, NPT, and other treaties regulating nuclear weapons. Other activities could be proscribed in connection with the prohibition of development.

There are strong reasons for being reasonably comprehensive. The nuclear ban treaty will set a normative standard for individuals and for future disarmament. It is not only about the legal rules for states that become parties in the near term. Further, specificity will clarify what activities parties must not allow that contribute to nuclear weapons work carried out by states outside the treaty.

One aspect of a development prohibition that received little attention is that monitoring and verifying compliance would be challenging. There are numerous activities related to nuclear and military technology that may or may not be considered part of a nuclear weapons program.8 Additionally, if an activity is intended to further development of nuclear weapons, it may not be easily detectable by observers from outside a country or by authorities within the country committed to compliance. An example is computer simulations of nuclear explosions.

These problems would be difficult ones even under optimal circumstances. In the case of a nuclear ban treaty initiated by non-nuclear-weapon states, a comprehensive verification regime beyond what is already provided by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and by the CTBT system is not envisaged. The treaty probably will affirm in some fashion that member-states are obligated to comply with IAEA safeguards agreements and certainly should do so. It should also be considered whether adherence to the additional protocol to safeguards agreements should be required, as Sweden advocated, or at least encouraged by the treaty.

Aside from the safeguarding of fissile materials and detection of nuclear explosive testing, verification of a development prohibition probably will not be possible over the near term. Monitoring will have to be done through peer review among states-parties, national intelligence, civil society monitoring, and whistleblowers, who ideally would be protected by the treaty. A mitigating factor is that, as a matter of global politics and implementation of the NPT, serious efforts at undertaking nuclear weapons programs draw much attention, even when not in violation of safeguards agreements. Inclusion of a prohibition will add a clear legal dimension to what is already a matter of intense scrutiny. In the event of accession of nuclear-armed states to the treaty, additional verification arrangements should be agreed.

Possession and Stockpiling

The nuclear ban treaty will include a prohibition on stockpiling, which is standard in weapons-prohibition treaties. In part, it will lay the groundwork for an obligation of nuclear-armed states to dismantle their arsenals. Also possible is a related prohibition on retention, which is found in existing treaties.

A prohibition on possession of nuclear weapons likely will also be part of a nuclear ban treaty. It is contained in the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties but not as such in other treaties prohibiting weapons. A prohibition on acquisition may be included in order to capture coming into possession by means other than manufacture. Some states seek to include a deployment prohibition. The fielding of nuclear forces is intrinsic to nuclear deterrence as practiced by possessor states. A deployment prohibition would explicitly reject that practice and underline that members of a nuclear ban treaty in no way must cooperate with the practice. A possible, related prohibition of stationing would similarly underline that treaty members may not host nuclear weapons, as certain members of NATO do under nuclear sharing arrangements.

In the same vein, a likely prohibition of transfer of nuclear weapons, applying in the first place to possessors of nuclear weapons who join the treaty, would also imply that a member of the treaty may not accept nuclear weapons from a possessor state outside the treaty. Such an action would be barred as well by a prohibition of acquisition.

The issue of nuclear weapons delivery vehicles received little attention from governments during the first week of negotiations, perhaps because making prohibitions applicable to delivery vehicles for states that have never had nuclear weapons seems unnecessary and unduly complicated. Yet, arms control experience in the U.S.-Soviet/Russian relationship indicates that control or elimination of delivery systems developed for nuclear weapons will be required for a successful global enterprise of eliminating existing nuclear arsenals. Also, a paragraph in the NPT preamble refers to "the elimination from national arsenals of nuclear weapons and the means of their delivery." The issue of delivery systems may be left aside for now and addressed in some way should nuclear-armed states later join the treaty.

Transit Prohibition

A prohibition on transit, supported by some states, would require treaty parties to be proactive, going beyond the requirements of the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties. It would require a state-party to ensure that nuclear weapons or their components do not traverse its territory and the air and water over which it has jurisdiction and control. In line with its minimalist approach, Austria opposed the inclusion of such a prohibition, which it said would require resolution of difficult practical issues such as demarcation of maritime and air space. Further, Austria maintained, a prohibition on assisting prohibited acts would bar granting of transit rights. Malaysia similarly stated that implementation of a prohibition on transit would be impractical and lead to technical discussions.

A counterargument is that all states are currently obligated by UN Security Council Resolution 1540 to adopt measures, including controls on transit and financing, to prevent nonstate actors from trafficking in nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons and their means of delivery, including related materials. A prohibition on transit of nuclear weapons, therefore, would not seem to increase the burden with respect to, for instance, commercial shipping. It still might raise issues with respect to activities of nuclear-armed states. On balance, inclusion of a prohibition on transit makes sense. Full implementation can be achieved over time based on experience and cooperation among treaty parties. In this respect and others, the regime could evolve.

Use and Threat of Use

The nuclear ban treaty will include a prohibition on use of nuclear weapons, probably on the model of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), in which states-parties undertake "never under any circumstances" to use chemical weapons. Another element of the CWC, a prohibition of engagement in any military preparations to use the specified weapons, is worth considering. It would go toward capturing the actions of participating in nuclear war planning, which also could be specifically proscribed, as Algeria recommended. Such provisions would be relevant in the event that states in military alliances with nuclear-armed states join the ban treaty.

There was some division of views during the opening negotiations regarding whether to include language prohibiting the threat of use. There is no such prohibition in the CWC and other treaties prohibiting and eliminating weapons, and there is a strong tendency to model the nuclear ban treaty on existing treaties. Further, several states, including Austria, Mexico, Sweden, and Switzerland, contended that the UN Charter prohibition of the threat of force suffices. Mexico went so far as to say that a specific prohibition on threat of use would call into question the integrity and scope of the UN Charter prohibition.

Arguments on the other side are powerful, and numerous states supported inclusion of a threat prohibition. As Chile said, the threat of use of nuclear weapons is the very foundation of nuclear deterrence, which has allowed the continued existence of the weapons jeopardizing security and survival. Nothing similar can be said about the other weapons already prohibited by treaties. Although useful guides, those treaties need not be slavishly followed. Moreover, in time of armed conflict—the most likely time when a specific threat of use would be made—the standard view is that international humanitarian law is the primary body of law governing the conduct of warfare, not the UN Charter. The International Court of Justice has stated that a threat to commit an act that would violate international humanitarian law is itself illegal.

A prohibition of threat of nuclear weapons use in times of peace and war would apply and reinforce the UN charter and international humanitarian law, not somehow undermine them. Further, as South Africa said, "a clear ban" on the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons "would be key to the effort to delegitimize the concept of nuclear deterrence."9 Ecuador stated that a threat prohibition is necessary in order to show that the concept has no place in international law.

A prohibition of threat of nuclear weapons use in times of peace and war would apply and reinforce the UN charter and international humanitarian law, not somehow undermine them. Further, as South Africa said, "a clear ban" on the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons "would be key to the effort to delegitimize the concept of nuclear deterrence."9 Ecuador stated that a threat prohibition is necessary in order to show that the concept has no place in international law.

Assistance with Prohibited Acts

There was widespread support for the inclusion of a prohibition on assistance with prohibited acts. As formulated in the CWC, states may not "assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a state-party" under the CWC. A similar prohibition in the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which established a nuclear-weapon-free-zone for Latin America and the Caribbean, requires states to "refrain from encouraging or authorizing, directly or indirectly, or in any way participating" in prohibited acts. Evidently, a prohibition along these lines would bar members of a nuclear ban treaty from cooperation or permitting cooperation relating to nuclear weapons in multiple ways with states outside the treaty. This could become relevant in circumstances now not foreseeable for any member of the treaty, but it would be particularly relevant to any state in a military alliance with a nuclear-armed state that joins the treaty.

In the view of some states, a prohibition on assistance with prohibited acts would extend to financing of nuclear weapons production, at least so far as the state’s own investments are concerned, as Ireland noted. Other states favored the inclusion of a specific prohibition on financing. Implementation of such a prohibition could be complex and demanding, especially if it requires states to regulate actions of persons under its jurisdiction. Still, over time it would be possible to develop a common understanding of what is entailed. It is certain that civil society will be calling on states in a future ban treaty to adopt national measures to prevent financing of nuclear weapons activities, whether or not a specific prohibition is included.

Implementation and Positive Obligations

Some support was expressed during the first week of negotiations for a provision similar to that found in other treaties requiring states to take appropriate measures to prevent any prohibited activity undertaken by persons or on territory under its jurisdiction and control. Another obligation receiving some support would require states to report on their implementation of the treaty. Support was also expressed for an obligation of international cooperation and assistance in relation to states’ implementation of the treaty.

Based on precedents set by the treaties on landmines and cluster munitions, nuclear ban treaty advocates have called for positive obligations of states in relation to assistance to victims.10 States are wary of taking on such obligations, especially given the absence of the nuclear-armed states that have been responsible for harm to individuals and the environment arising from testing and use. Still, there is widespread support for a recognition of the rights of victims, at least in the preamble but perhaps as an obligation. This is natural because the negotiations have grown out of the conferences on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear explosions. Some support was also expressed for positive obligations on environmental remediation, disarmament education, and awareness raising of nuclear weapons risks.

Institutional Arrangements and Final Clauses

Many states supported providing for periodic review conferences of a treaty. Brazil also proposed providing for possible extraordinary sessions, which could negotiate a general plan for destruction of nuclear arsenals and measures related to a non-discriminatory verification regime.

There was also support for establishing an administrative body, which could prepare review conferences, assist states with implementation, and promote treaty aims. Based on the initial discussions, it likely would be quite modest in scope. As noted, at the outset there likely will not be a monitoring or verification capability focused on non-nuclear-weapon states’ implementation beyond what any reporting requirement and review conference assessment provide and the existing roles of the IAEA and the CTBT system.

Discussion of provisions for nuclear-armed states to join the treaty reflected two premises: All states are welcome and encouraged to become parties, and the treaty aims to contribute to the establishment of a world free of nuclear weapons. Yet, nuclear-armed states becoming parties to the treaty is entirely theoretical at this point. If they do decide to eliminate their arsenals, they may do so without joining the treaty. Accordingly, negotiators generally do not want to craft extensive provisions on the matter, but rather desire to create flexibility so that this can be satisfactorily addressed if and when it arises.

The two main mechanisms considered for accession of nuclear-armed states are that a nuclear-armed state would verifiably dismantle its arsenal before joining the treaty or, at the time of joining the treaty, a nuclear-armed state would be subject to a time-bound obligation to dismantle verifiably its arsenal; the obligation and the accompanying arrangements would be subject to approval by treaty members. The treaty could provide for both possibilities. Ensuring compliance with the treaty by nuclear-armed states and nuclear ally states as well could be facilitated by requiring that each state adhering to the treaty provide a declaration regarding whether it possesses nuclear weapons and whether they are located in any place under its jurisdiction or control. Such a requirement is found in the CWC.

Some attention was paid to final clauses, among them those relating to entry into force and withdrawal. Numerous states supported a clause on entry into force requiring only that a set number of states ratify the treaty, with proposed figures ranging from 25 to 80.

Concerning withdrawal, New Zealand expressed a preference for having no clause contemplating that states might withdraw, given that the treaty will set a global norm prohibiting nuclear weapons. South Africa opposed a withdrawal clause on the ground that the matter is adequately regulated by general rules of international law. They might permit withdrawal, for example, based on an unforeseeable "fundamental change of circumstances." A countervailing factor, as New Zealand recognized, is that having a withdrawal provision makes it easier for states to join a treaty.

Other states favored having a withdrawal clause subject to strict requirements, such as a lengthy period of notification and review, consideration by a meeting of states-parties, and exclusion of its exercise during armed conflict involving the withdrawing state. Brazil stated that the NPT withdrawal clause could serve as a basis to which additional criteria would be added. The NPT requires that the withdrawing state notify states-parties and the UN Security Council that it has decided extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of the treaty, have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country.

Clearly, the question of how to handle, indeed whether to permit, withdrawal would be crucial for a global treaty eliminating nuclear weapons. It perhaps is less important in the case of a treaty focused on prohibitions, given that there seems no near-term prospect of participation by nuclear-armed states. Nonetheless, it would seem best, at a minimum, to impose stringent requirements on withdrawal.11

Preamble Content

The preamble is important in a typical treaty because it provides guidance as to interpretation and application of the treaty. In the case of a nuclear weapons prohibition treaty, the preamble assumes added importance because the treaty in part is aiming to affirm and advance normative standards and, in so doing, educate the world about the imperatives of nonuse and elimination of such weapons.

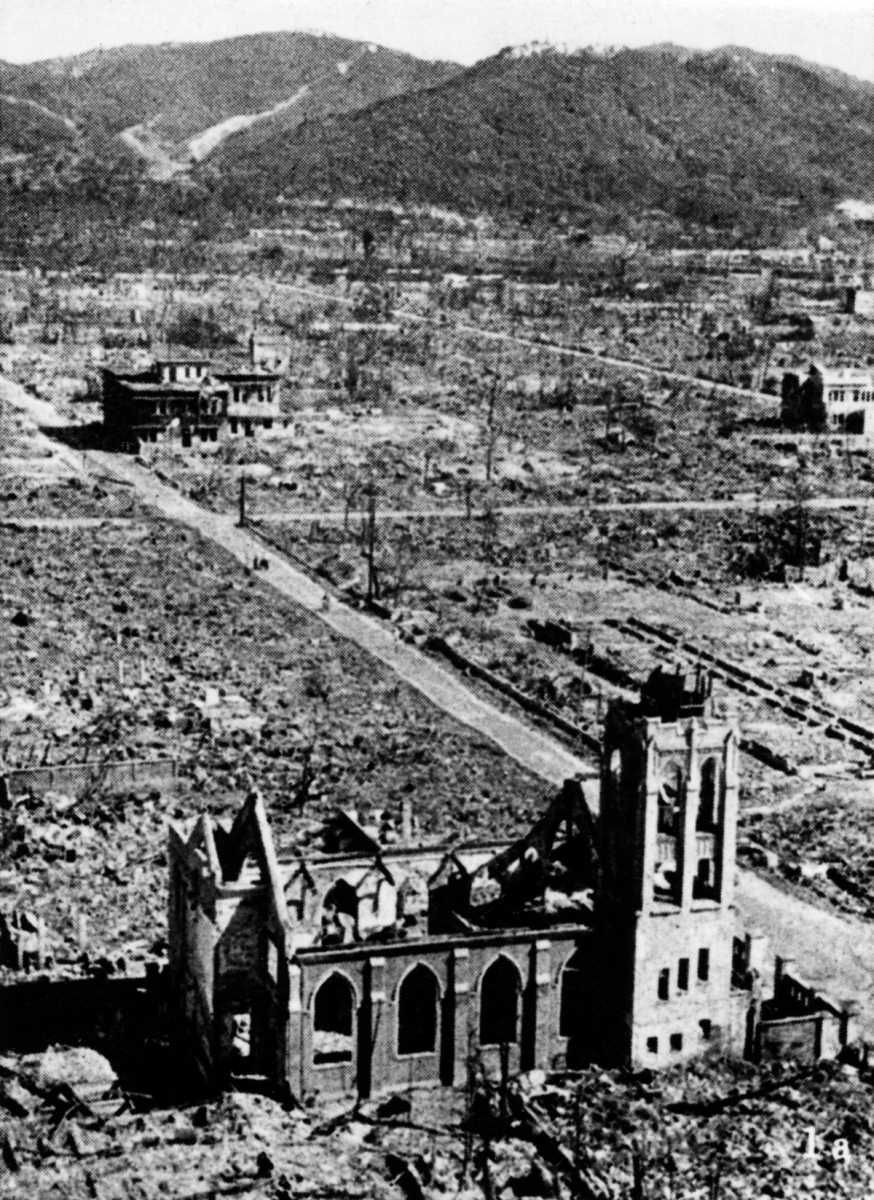

From both governmental and civil society participants, there were numerous proposals on preamble content. They included calls for the preamble to refer to the humanitarian consequences of nuclear explosions; the grounding of the treaty in fundamental rules of international humanitarian law; the obligation to ensure respect for international humanitarian law; the obligation to pursue in good faith and conclude negotiations on nuclear disarmament; the role of the treaty in achieving a world free of nuclear weapons; the contribution of the treaty to the objective of general and complete disarmament; the contribution of the treaty to the three pillars of the United Nations: peace and security, human rights, and development; the role of public conscience, including the voices of the hibakusha and other victims of nuclear weapons, in banning nuclear weapons; and more.

From both governmental and civil society participants, there were numerous proposals on preamble content. They included calls for the preamble to refer to the humanitarian consequences of nuclear explosions; the grounding of the treaty in fundamental rules of international humanitarian law; the obligation to ensure respect for international humanitarian law; the obligation to pursue in good faith and conclude negotiations on nuclear disarmament; the role of the treaty in achieving a world free of nuclear weapons; the contribution of the treaty to the objective of general and complete disarmament; the contribution of the treaty to the three pillars of the United Nations: peace and security, human rights, and development; the role of public conscience, including the voices of the hibakusha and other victims of nuclear weapons, in banning nuclear weapons; and more.

Austria urged that the preamble reference the findings of the Oslo, Nayarit, and Vienna conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons use, including "that impact of a nuclear weapon detonation, irrespective of the cause, would not be constrained by national borders and could have regional and even global consequences, causing destruction, death and displacement as well as profound and long-term damage to the environment, climate, human health and well-being, socioeconomic development, [and] social order and could even threaten the survival of humankind." This seems appropriate in that the negotiations have their genesis in those conferences.

Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Egypt, Iran, Liechtenstein, New Zealand, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and others proposed that the preamble recognize or reflect the incompatibility of use of nuclear weapons with international humanitarian law. Citing the late Judge Christopher Weeramantry, Sri Lanka said that the "illegality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstances could be the key underlying principle that could drive a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons." For other states, there appears to be some reluctance to venture in this manner into contested terrain, contested above all by the nuclear-armed states, but the reasons to do so are compelling.

An affirmation of the illegality of use would reinforce the norm of nonuse of nuclear weapons. The norm arises out of a broad but not universal recognition that use of nuclear weapons is incompatible with international humanitarian law and the practice of nonuse of such weapons in war since 1945. Also, the core operative prohibitions of the treaty will apply only to states-parties. Any implication that nonparty states are permitted to use nuclear weapons must be avoided. An affirmation of illegality of use is one way of doing so.

Another important means of underlining that states outside the treaty cannot escape the fundamental prohibitions it codifies would be to include the famous Martens Clause found in international humanitarian law treaties and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Here it would provide that, in cases not covered by the nuclear weapons prohibition treaty or by other international agreements, civilians and combatants remain under the protection and authority of the principles of international law, derived from established custom, the principles of humanity, and the dictates of public conscience.

Conclusion

During the first week of negotiations, diplomats and civil society were energized, even passionate, and worked constructively. A fresh wind is blowing in the stagnant nuclear disarmament sphere. All signs are that the energy will carry through into the demanding second session of negotiations. It will be needed to successfully meet the challenges not only of reflecting the results of the initiative on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons use, but also codifying and advancing law relating to development, possession, and use of nuclear weapons and helping shape future elimination of nuclear arsenals.

ENDNOTES

1. UN General Assembly, "Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations," A/RES/71/258, 11 January 2017. It was adopted by a vote of 130 to 37, with 15 abstentions on December 23, 2016.

2. For statements on the positions of governments, see Reaching Critical Will, "Statements from the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty Negotiations," n.d., http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/statements; United Nations, "United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards Their Total Elimination," n.d., https://www.un.org/disarmament/ptnw/index.html. In some cases, diplomats made remarks not contained in the statements.

3. UN General Assembly, "Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations," A/RES/71/258, 11 January 2017.

4. For a useful analysis of many of the issues under negotiation, see John Borrie et al., "A Prohibition on Nuclear Weapons: A Guide to the Issues," International Law and Policy Institute and the UN Institute for Disarmament Research, February 2016, http://unidir.org/files/publications/pdfs/a-prohibition-on-nuclear-weapons-a-guide-to-the-issues-en-647.pdf.

5. A prohibition of development is not contained in the Treaty of Tlatelolco or the Treaty of Rarotonga.

6. Treaty of Pelindaba and the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia.

7. This is the approach taken by the Central Asian nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaty.

8. See United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards Their Total Elimination, "Topic 2: Core Prohibitions," A/CONF.229/2017/NGO/WP.18, March 31, 2017.

9. See also International Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms, "Selected Elements of a Treaty Prohibiting Nuclear Weapons," IALANA Discussion Paper, March 24, 2017, http://lcnp.org/pubs/2017/IALANA/IALANA%20Discussion%20Paper%201.0final.pdf.

10. See United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards Their Total Elimination, "Positive Obligations in a Treaty Prohibiting Nuclear Weapons: Stockpile Destruction, Environmental Remediation, and Victim Assistance," A/CONF.229/2017/NGO/WP.10. March 27, 2017.

11. See United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards Their Total Elimination, "Withdrawal Clauses in Arms Control Treaties: Some Reflections About a Future Treaty Prohibiting Nuclear Weapons," A/CONF.229/2017/NGO/WP.13, March 31, 2017.

The ban treaty could adopt a simple verification obligation using language similar to that in the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties, while recognizing that some verification obligations already exist and more stringent verification may be necessary as nuclear-weapon states transition to join the treaty. For example, the treaty could require parties to maintain the nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation obligations they had in force as of January 1, 2017, and to accept as soon as possible the most stringent such measures available and to accept all future safeguards, monitoring, and verification obligations as agreed by the ban treaty conference of parties. This would create a stable, common verification baseline as of the start of the negotiations and a mechanism for the agreed evolution and improvement of the verification regime over time.

The ban treaty could adopt a simple verification obligation using language similar to that in the nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties, while recognizing that some verification obligations already exist and more stringent verification may be necessary as nuclear-weapon states transition to join the treaty. For example, the treaty could require parties to maintain the nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation obligations they had in force as of January 1, 2017, and to accept as soon as possible the most stringent such measures available and to accept all future safeguards, monitoring, and verification obligations as agreed by the ban treaty conference of parties. This would create a stable, common verification baseline as of the start of the negotiations and a mechanism for the agreed evolution and improvement of the verification regime over time. It is reasonable to assume that a South African-style verification of warhead dismantlement and accounting of fissile material production would be a much more difficult task, may take several decades to complete, and may be fraught with large uncertainties. It would be much more manageable if verification was agreed in advance and nuclear warhead dismantlement and destruction and material disposition actually observed to ensure the process met agreed standards.

It is reasonable to assume that a South African-style verification of warhead dismantlement and accounting of fissile material production would be a much more difficult task, may take several decades to complete, and may be fraught with large uncertainties. It would be much more manageable if verification was agreed in advance and nuclear warhead dismantlement and destruction and material disposition actually observed to ensure the process met agreed standards.

Some of these measures go beyond what is part of the current IAEA safeguards system. The IAEA, however, already complements its on-site monitoring equipment and inspections with open-source information and satellite imagery as part of an "all source" approach.

Some of these measures go beyond what is part of the current IAEA safeguards system. The IAEA, however, already complements its on-site monitoring equipment and inspections with open-source information and satellite imagery as part of an "all source" approach. The recognition of the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons underpins all approaches toward a world free of such weapons. Meanwhile, North Korea’s nuclear and missile development has now reached a new level and is posing a real threat to the region and beyond. This is a challenge to the international nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime centered on the [nuclear] Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT).

The recognition of the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons underpins all approaches toward a world free of such weapons. Meanwhile, North Korea’s nuclear and missile development has now reached a new level and is posing a real threat to the region and beyond. This is a challenge to the international nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime centered on the [nuclear] Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). The United States and Russia have reduced their Cold War stockpiles and verifiably banned nuclear explosive testing. But some 15,000 weapons remain, additional nuclear-armed states have emerged, and the risk of nuclear weapons use is rising.

The United States and Russia have reduced their Cold War stockpiles and verifiably banned nuclear explosive testing. But some 15,000 weapons remain, additional nuclear-armed states have emerged, and the risk of nuclear weapons use is rising. The 2020 review conference assumes additional importance following the failure of the 2015 review conference to produce a consensus document and the growing frustration of the non-nuclear-weapon states at the lack of action by nuclear powers, particularly the United States and Russia, to deliver on their legally binding disarmament obligations under the 1968 treaty. A second consecutive failure would risk weakening the global nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime, including efforts to block nuclear weapons activities by Iran and North Korea.

The 2020 review conference assumes additional importance following the failure of the 2015 review conference to produce a consensus document and the growing frustration of the non-nuclear-weapon states at the lack of action by nuclear powers, particularly the United States and Russia, to deliver on their legally binding disarmament obligations under the 1968 treaty. A second consecutive failure would risk weakening the global nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime, including efforts to block nuclear weapons activities by Iran and North Korea. Russia also rejected the ban negotiations. “The conceptual framework of the negotiation process, which in effect ignores the strategic context and addresses the elimination of nuclear weapons in isolation from existing realities, is unacceptable for us,” Russian Ambassador Mikhail Ulyanov said in a May 5 statement.

Russia also rejected the ban negotiations. “The conceptual framework of the negotiation process, which in effect ignores the strategic context and addresses the elimination of nuclear weapons in isolation from existing realities, is unacceptable for us,” Russian Ambassador Mikhail Ulyanov said in a May 5 statement. The envisioned treaty reflects an historic effort to shift international norms against the acquisition, possession, and potential use of nuclear weapons. The international effort is pressed by non-nuclear-weapons states and rejected by nuclear-armed countries that see the ban as impractical and potentially destabilizing if it undermines nuclear deterrence.

The envisioned treaty reflects an historic effort to shift international norms against the acquisition, possession, and potential use of nuclear weapons. The international effort is pressed by non-nuclear-weapons states and rejected by nuclear-armed countries that see the ban as impractical and potentially destabilizing if it undermines nuclear deterrence. North Korea tested the missile at a lofted trajectory, so it flew higher than a normal flight pattern and traveled about 700 kilometers to splash down in the Sea of Japan. David Wright, co-director of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, used data from the test to calculate a 4,800-kilometer range at a standard ballistic missile trajectory, according to his organization’s blog, “All Things Nuclear.” The lofted trajectory was likely used to avoid the missile splashing down too close to another country.

North Korea tested the missile at a lofted trajectory, so it flew higher than a normal flight pattern and traveled about 700 kilometers to splash down in the Sea of Japan. David Wright, co-director of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, used data from the test to calculate a 4,800-kilometer range at a standard ballistic missile trajectory, according to his organization’s blog, “All Things Nuclear.” The lofted trajectory was likely used to avoid the missile splashing down too close to another country. Washington’s statement after the missile test, however, took a more strident tone. The White House statement on May 13 called North Korea a “flagrant menace” and said all states must implement stronger sanctions against North Korea. The statement also noted Washington’s “ironclad commitment” to U.S. allies.

Washington’s statement after the missile test, however, took a more strident tone. The White House statement on May 13 called North Korea a “flagrant menace” and said all states must implement stronger sanctions against North Korea. The statement also noted Washington’s “ironclad commitment” to U.S. allies.