June 2019

By Michael T. Klare

Speed. Since nations first went to war, speed has been a key factor in combat, particularly at the very onset of battle. The rapid concentration and employment of force can help a belligerent overpower an opponent and avoid a costly war of attrition, an approach that underlaid Germany’s blitzkrieg (lightning war) strategy during World War II and America's “shock and awe” campaign against Iraq in 2003.

Speed is also a significant factor in the nuclear attack and deterrence equation. Following the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the late 1950s, which reduced to mere minutes the time between a launch decision and catastrophic destruction on the other side of the planet, nuclear-armed states have labored to deploy early-warning and command-and-control systems capable of detecting a missile launch and initiating a retaliatory strike before their own missiles could be destroyed. Preventing the accidental or inadvertent onset of nuclear war thus requires enough time for decision-makers to ascertain the accuracy of reported missile launches and choose appropriate responses. This is an imperative reinforced by several Cold War incidents in which launch detection systems provided false indications of such action but human operators intervened to prevent unintended retaliation.

Speed is also a significant factor in the nuclear attack and deterrence equation. Following the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the late 1950s, which reduced to mere minutes the time between a launch decision and catastrophic destruction on the other side of the planet, nuclear-armed states have labored to deploy early-warning and command-and-control systems capable of detecting a missile launch and initiating a retaliatory strike before their own missiles could be destroyed. Preventing the accidental or inadvertent onset of nuclear war thus requires enough time for decision-makers to ascertain the accuracy of reported missile launches and choose appropriate responses. This is an imperative reinforced by several Cold War incidents in which launch detection systems provided false indications of such action but human operators intervened to prevent unintended retaliation.

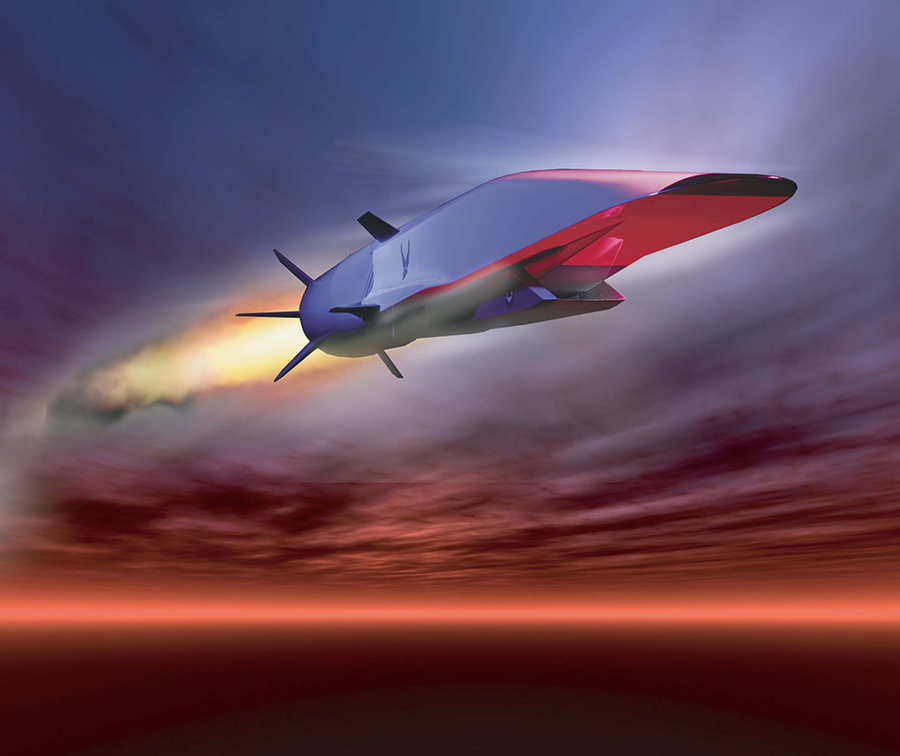

Today, speed will alter the calculus of combat and deterrence even further with the imminent deployment of hypersonic weapons—maneuverable vehicles that fly at more than five times the speed of sound (Mach 5 and higher). China, Russia, and the United States are testing hypersonic weapons of various types to enhance strategic nuclear deterrence and strengthen front-line combat units. Existing ICBM reentry vehicles also travel at those superfast speeds, but the hypersonic glide vehicles now in development are far more maneuverable, making their tracking and interception nearly impossible. Such dual-use vehicles, capable of carrying nuclear or conventional warheads, are also being fitted on missiles intended for use in a regional context, say, in a battle erupting in the Baltic region or the South China Sea. With the time between launch and arrival on target dwindling to 10 minutes or less, the introduction of these weapons will introduce new and potent threats to global nuclear stability.

Hypersonic weapons are said by proponents to be especially useful at the onset of battle, when they can attack an opponent’s high-value targets, including air defense radars, fighter bases, missile batteries, and command-and-control facilities. The incapacitation of those facilities at an early stage in the conflict could help smooth the way for follow-on attacks by regular air, sea, and ground forces. Yet, as the same facilities are often tied into a nuclear-armed country’s nuclear warning and command systems, attacks against them could be interpreted by the target state as the prelude to a disarming first strike and trigger the early use of its own nuclear weapons.

From an arms control perspective, the deployment of hypersonic weapons raises a host of additional concerns, beginning with the possible violation by some of the proposed missiles of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The treaty’s prospects are bad enough with the U.S. announcement last February that it will withdraw from the treaty in August, but deployment of treaty-prohibited hypersonic weapons would certainly torpedo any chance of preserving the pact. More complications arise from some countries’ plans to place hypersonic delivery vehicles on ICBMs, which would indirectly bring any such U.S. or Russian systems under the limits set by the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), even if the hypersonic components contained conventional warheads. Any negotiation of a successor to New START, which is due to expire in 2021 unless extended, would likely involve discussion of accounting for hypersonic munitions.1

The rush to develop and deploy hypersonic weapons without fully considering their intended uses and strategic impacts is yet another aspect of the speed associated with these munitions. Given the escalatory dangers of deploying hypersonic weapons, it is essential that they receive closer attention from policymakers, arms control analysts, and the general public.

Hypersonic Developments

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union conducted research into mounting maneuverable reentry vehicles on long-range ballistic missiles, but militaries began to explore a variety of hypersonic weapons types in the 21st century. Multiple programs are now approaching the test and deployment stage. In this process, the major powers have largely focused on two types of weapons: hypersonic glide vehicles and hypersonic cruise missiles.2

Hypersonic glide vehicles, also called boost-glide weapons, employ a booster rocket to carry the glide vehicle into the outer atmosphere. Once reaching that altitude, between 40 and 100 miles above the earth’s surface, the vehicle separates from the booster and, propelled solely by its momentum and kept aloft by its aerodynamic shape, skims along the atmosphere’s outer boundary for great distances. Although unpowered, the vehicle can maneuver in flight, using satellite guidance to strike with high precision.

The U.S. Department of Defense, as part of its prompt global-strike program, initially considered launching conventionally armed hypersonic glide vehicles from repurposed Minuteman ICBMs and placing conventional warheads on a small number of intercontinental Trident submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Later, the Pentagon largely abandoned that approach, worried that such systems could be confused for nuclear-armed ballistic missiles and unintentionally trigger a nuclear response. More recently, the Pentagon has pursued medium-range systems employing assorted rockets to boost the glide vehicle into space. Russia and China, however, are continuing to test and deploy ICBM-launched hypersonic glide vehicles, notably the Russian Avangard and Chinese DF-ZF.

The U.S. Department of Defense, as part of its prompt global-strike program, initially considered launching conventionally armed hypersonic glide vehicles from repurposed Minuteman ICBMs and placing conventional warheads on a small number of intercontinental Trident submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Later, the Pentagon largely abandoned that approach, worried that such systems could be confused for nuclear-armed ballistic missiles and unintentionally trigger a nuclear response. More recently, the Pentagon has pursued medium-range systems employing assorted rockets to boost the glide vehicle into space. Russia and China, however, are continuing to test and deploy ICBM-launched hypersonic glide vehicles, notably the Russian Avangard and Chinese DF-ZF.

Hypersonic cruise missiles, unlike glide vehicles, fly within the atmosphere and can be launched by ships or planes or from land. To attain Mach 5 and above, they employ advanced, air-breathing jet engines, such as scramjets (supersonic combustion ramjets). Because the missiles must carry their fuel, they have less range than glide vehicles and must be launched from sites closer to their target. The U.S. Air Force is pursuing an air-launched hypersonic cruise missile, and Russia has been testing the Tsirkon, will which be launched from ships and submarines.

All three countries are also working on variants of these models and the necessary supporting technologies. The U.S. Air Force, alongside its hypersonic cruise missile program, is financing a separate effort to develop a hypersonic projectile it calls the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon. The U.S. Army is proceeding with development of its Alternative Re-Entry System, a maneuverable hypersonic delivery vehicle that could be launched by a number of proposed missile booster systems. Not to be outdone, the U.S. Navy is developing a booster rocket that could be fired from submarines or surface ships to carry hypersonic vehicles. The Defense Department asked for $2.6 billion for these and related initiatives in its fiscal year 2020 budget request, with far larger amounts expected in future budgets.

Strategic Rationales

All three major powers have explored similar applications of hypersonic technologies, but their strategic calculations in doing so appear to vary, with the United States primarily seeking weapons for use in a regional, non-nuclear conflict and Russia emphasizing the use of hypersonic weapons for both conventional and nuclear applications. Whatever the case, the speed of attack largely accounts for the growing pursuit of hypersonic weaponry, along with their extensive maneuverability and perceived invulnerability to existing defensive systems.

The United States first looked at hypersonic weapons as part of a desired capacity to attack an enemy’s high-value targets, including command-and-control systems and mobile missile batteries, without using nuclear warheads or relying on forward-based forces. This was the original premise of the prompt global-strike mission, first announced in 2003. Over time, however, the U.S. pursuit of hypersonic weaponry has focused more on conventionally armed, intermediate-range weapons that might be used in a regional context to degrade an enemy’s defenses at the onset of battle, thereby easing the way for follow-on air, sea, and ground forces. Despite this shift, speed of attack has remained a consistent aim of the Pentagon’s hypersonic endeavors. As noted by the Congressional Research Service in a January 2019 review of these efforts, “Analysts have identified a number of potential targets that the United States might need to strike promptly.” These could include “air defense or anti-satellite weapons that could disrupt the U.S. ability to sustain an attack,” an enemy’s command and control facilities, or “caches of weapons of mass destruction.”3

The United States first looked at hypersonic weapons as part of a desired capacity to attack an enemy’s high-value targets, including command-and-control systems and mobile missile batteries, without using nuclear warheads or relying on forward-based forces. This was the original premise of the prompt global-strike mission, first announced in 2003. Over time, however, the U.S. pursuit of hypersonic weaponry has focused more on conventionally armed, intermediate-range weapons that might be used in a regional context to degrade an enemy’s defenses at the onset of battle, thereby easing the way for follow-on air, sea, and ground forces. Despite this shift, speed of attack has remained a consistent aim of the Pentagon’s hypersonic endeavors. As noted by the Congressional Research Service in a January 2019 review of these efforts, “Analysts have identified a number of potential targets that the United States might need to strike promptly.” These could include “air defense or anti-satellite weapons that could disrupt the U.S. ability to sustain an attack,” an enemy’s command and control facilities, or “caches of weapons of mass destruction.”3

Such a capacity would be particularly useful, U.S. strategists believe, in any future engagement with Chinese forces in the Asia-Pacific region, such as in the South China Sea or around Taiwan. Since President Barack Obama announced a “pivot to the Pacific” in 2011, U.S. military planners have sought advanced weaponry to counter what are viewed as enhanced Chinese defensive military capabilities. China, it is claimed, has deployed many intermediate-range ballistic missiles to target U.S. warships and bases in the region; a U.S. preemptive strike on those capabilities using hypersonic weapons at the onset of a conflict would help safeguard key U.S. assets and pave the way for follow-on attacks.4 China also appears to be focusing its hypersonic efforts on a regional context, with its DF-ZF glide vehicle apparently aimed at U.S. bases, warships, and missile batteries in the Asia-Pacific theater.5

Russia seems to have been driven by somewhat different intentions. After the United States withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, Russian officials worried that unconstrained U.S. missile defenses could someday threaten Russia’s strategic deterrent. To overcome that risk, Russia says it will soon deploy a nuclear-armed, maneuverable hypersonic delivery system, the Avangard, on some of its ICBMs.6 With its speed and maneuverability, the Avangard is designed to evade any existing or future U.S. anti-missile systems, thereby ensuring the integrity of Russia’s strategic deterrent. “This is a major event in the life of the armed forces and, perhaps, in the life of the country,” Russian President Vladimir Putin told government officials last December. “Russia now has a new kind of strategic weapon.”7

Russia seems to have been driven by somewhat different intentions. After the United States withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, Russian officials worried that unconstrained U.S. missile defenses could someday threaten Russia’s strategic deterrent. To overcome that risk, Russia says it will soon deploy a nuclear-armed, maneuverable hypersonic delivery system, the Avangard, on some of its ICBMs.6 With its speed and maneuverability, the Avangard is designed to evade any existing or future U.S. anti-missile systems, thereby ensuring the integrity of Russia’s strategic deterrent. “This is a major event in the life of the armed forces and, perhaps, in the life of the country,” Russian President Vladimir Putin told government officials last December. “Russia now has a new kind of strategic weapon.”7

Although Russia has placed its primary emphasis on the development of hypersonic warheads for some of its strategic ICBMs, it has also pursued dual-use weapons intended for theater use, presumably against NATO forces in Europe and the Atlantic. That is the apparent intent of its air-launched, anti-ship missile, called Kinzhal, said to have a range of 1,200 miles while flying at speeds approaching Mach 10, evading any defenses.8

Arms Racing Behavior

Each of these countries initiated its pursuit of hypersonic weapons for unique strategic purposes, but all seem to have recently accelerated their efforts partly to overtake progress made by their rivals—behavior that has all the earmarks of a classic arms race.

“China’s hypersonic weapons development outpaces ours,” Admiral Harry Harris, then commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and now ambassador to South Korea, told Congress last year in a bid for higher U.S. spending on such munitions. Another top official, Michael Griffin, undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, said the United States must pump more money into hypersonic development if it is to regain its technological edge. “The United States is not yet doing all that we need to do to respond to hypersonic missile threats,” he said last year. “I did not take this job to reach parity with adversaries. I want to make them worry about catching up with us again.”9

Whether China or Russia has overtaken the United States in hypersonic weaponry is a matter of debate. Both assert they are ready to deploy hypersonic weapons, but it is unclear if those munitions are truly as capable as claimed. Furthermore, with each of these countries driven by their specific goals, the United States likely enjoys significant technological advantages in those types of hypersonic weapons it seeks for its own arsenal. It would be misleading, therefore, to claim that the United States is behind in a hypersonic arms race.10

Nevertheless, the need to ensure a U.S. technological advantage in hypersonic weapons has been underscored by the nation’s top defense contractors, many of which expect to benefit from higher spending in this area. “From a pure business perspective, there is a significant opportunity in the hypersonic domain,” said Raytheon Vice President Thomas Bussing at a December 2018 meeting of military contractors. Indeed, the hypersonic weapons market could be worth “many billions of dollars,” said Loren Thompson, a defense analyst who works with Lockheed Martin and other big firms. “We’re talking about an entirely new class of weapons and the operating concepts to go with it.”11

These comments, along with others by senior military officials in China, Russia, and the United States, highlight another way in which hypersonic weapons and speed are closely related: there is a rush to move these weapons from the design stage to mass production and deployment. “This is not primarily a research effort,” Griffin said at the December meeting of military contractors. “It is an effort to get these systems into the field in the thousands.…We are going to have to create a new industrial base for these systems.” Unfortunately, this rush to “industrialize” the production of hypersonic weapons is occurring in the absence of sufficient discussion of the escalatory and arms control implications of fielding these munitions.

Escalation Risks and ‘Entanglement’

Many weapons can be employed for offensive and defensive purposes, but hypersonic weapons, especially those designed for use in a regional context, are primarily intended to be used offensively, to destroy high-value enemy assets, including command-and-control facilities. This raises two major concerns: the risk of rapid escalation from a minor crisis to a full-blown war and the unintended escalation from conventional to nuclear warfare.

That hypersonic weapons are being designed for offensive use at an early stage in a conflict has been evident in U.S. strategic policy from the beginning. Claiming that a major adversary might try to hide or move critical assets at the outbreak of a crisis to protect them from U.S. air and missile strikes, the Pentagon hoped the prompt global-strike program would enable U.S. forces to attack those targets with minimal warning. As this program got under way, hypersonic weapons became the technology of choice for its implementation. “Systems that operate at hypersonic speeds…offer the potential for military operations from longer ranges with shorter response times and enhanced effectiveness compared to current military systems,” states the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Such munitions, it adds, “could provide significant payoff for future U.S. offensive strike operations, particularly as adversaries’ capabilities advance.”12 Most of the hypersonic weapons being developed by the U.S. military, including the Air Force cruise missile and the Navy’s sea-launched system, are intended for strikes against key enemy assets at an early stage of conflict, when speed confers a significant advantage. Certain Russian weapons, such as the Kinzhal, also seem intended for this purpose.

Some analysts fear that the mere possession of such weapons might induce leaders to escalate a military clash at the very outbreak of a crisis—believing their early use will confer a significant advantage in any major engagement that follows—while reducing the chances of keeping the fighting limited. It is easy to imagine, for example, how a clash between U.S. and Chinese naval vessels in the South China Sea, accompanied by signs of an air and naval mobilization on either or both sides, might prompt one combatant to launch a barrage of hypersonic weapons at all those ships and planes and their command-and-control systems, hoping to prevent their use in any full-scale encounter. This might make sense from a military perspective, but would undoubtedly prompt a fierce counterreaction from the injured side and restrict efforts to halt the fighting at a lower level of violence.

The introduction of hypersonic weapons also raises concerns over the escalation from conventional to nuclear warfare. The United States has focused primarily on the development of hypersonic weapons carrying conventional warheads, but there is no fundamental reason why they could not be nuclear armed. Indeed, Russia’s Avangard missile is intended to deliver a nuclear warhead, and it is assumed that China’s DF-ZF is also designed with this in mind.

This leads to what is called “warhead ambiguity”: the risk that a defending nation, aware of an enemy’s hypersonic launch and having no time to assess the warhead type, will assume the worst and launch its own nuclear weapons.13 Concern over this risk has led the U.S. Congress to bar funding for the development of ICBM-launched hypersonic glide vehicles, thereby helping to propel the Pentagon’s shift away from such systems and toward the development of medium-range weapons more suitable for use in a regional context. Nevertheless, warhead ambiguity will remain a feature of any future landscape involving the deployment of multiple hypersonic weapons, as a defender will never be certain that an enemy’s assault is entirely non-nuclear. With as little as five minutes to assess an attack—the time it would take a hypersonic glide vehicle to traverse 2,000 miles—a defender would be understandably hard pressed to avoid worst-case assumptions.

Equally worrisome is the danger of “target ambiguity”: the possibility that a hypersonic attack, even if conducted with missiles known to be armed only with conventional warheads, would endanger the early-warning and command-and-control systems a defender uses for its nuclear and conventional forces, leading it to fear the onset of a nuclear attack. This is especially dangerous in light of what James Acton, a security analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, calls the “entanglement” problem. Although almost everything involving nuclear decision-making is secret, the nuclear and conventional command-and-control systems of the major powers are widely assumed to be interconnected, or entangled, making it difficult to clearly distinguish one from another. Therefore, any attack on command-and-control facilities at the onset of crisis, however intended, could be interpreted by the defender as a prelude to a nuclear rather than a conventional attack and prompt the defender to launch its own nuclear weapons before they are destroyed by an anticipated barrage of enemy bombs and missiles.14

All this points to yet another concern related to the impact of emerging technologies on the future battlefield: the risk that nuclear-armed nations, fearing scenarios of just this sort, will entrust more and more of their critical decision-making to machines, fearing that humans will not be able to make reasoned judgments under such enormous time pressures. With hypersonic weapons in the arsenals of the major powers, military leaders may conclude that sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) systems should be empowered to determine the nature of future missile attacks and select the appropriate response. This is a temptation that can only increase as hypersonic weapons are themselves equipped with AI systems, a capability being developed at Sandia National Laboratories, enabling them to select and navigate to an array of potential targets.15 This convergence of advanced technologies is one of the greatest concerns of analysts who fear the loss of human control over the pace of combat. Paul Scharre, a program director at the Center for a New American Security, has warned of a “flash war” erupting when machines misinterpret radar signals and initiate catastrophic, possibly nuclear responses. “Competitive pressures in fast-paced environments threaten to push humans further and further out of the loop,” he wrote. “With this arms race in speed come grave risks,” including “a war that spirals out of control in mere seconds.”16

Inserting Speed Bumps

Given the risks posed by hypersonic weapons, especially when their deployment is paired with other technological developments, it is essential to consider measures for minimizing the dangers they pose to nuclear stability and the war-and-peace equation. This will take time: the technologies involved in these systems remain largely unproven, and the strategic rationale for their deployment has yet to be fully demonstrated. Meanwhile, military and government officials should slow the process of hypersonic weapons acquisition to provide strategists and policymakers adequate time to assess their potential utility and escalatory risks.

One approach for slowing things down would be an international moratorium on flight tests of hypersonic weapons.17 Such an arrangement might seem out of reach, but all major powers have reason to fear the early deployment of hypersonic weapons by their rivals. Therefore, a moratorium on testing, to allow time for other control measures to be considered, is well worth pursuing.

If leaders of the major powers are prepared to discuss constraints on developing and deploying hypersonic weapons, they could adopt a number of approaches. One would be to establish strict limits on deployable numbers of such weapons or prohibit their deployment altogether, moves that would eliminate most or all of the risks posed by these weapons. Again, although no doubt seeming a remote possibility, such measures would help shield all the major powers from an acute threat against which they possess few if any defenses. A possible venue for discussing such measures would be the strategic stability talks that were once held by U.S. and Russian officials. The first round of these talks convened in September 2017 in Helsinki, and a second round was scheduled for March 2018 in Vienna, but Moscow cancelled in light of growing bilateral tensions. Russia has recently expressed interest in resuming these talks, and it is reasonable to assume that hypersonic weapons limitations would be on the agenda.

If leaders of the major powers are prepared to discuss constraints on developing and deploying hypersonic weapons, they could adopt a number of approaches. One would be to establish strict limits on deployable numbers of such weapons or prohibit their deployment altogether, moves that would eliminate most or all of the risks posed by these weapons. Again, although no doubt seeming a remote possibility, such measures would help shield all the major powers from an acute threat against which they possess few if any defenses. A possible venue for discussing such measures would be the strategic stability talks that were once held by U.S. and Russian officials. The first round of these talks convened in September 2017 in Helsinki, and a second round was scheduled for March 2018 in Vienna, but Moscow cancelled in light of growing bilateral tensions. Russia has recently expressed interest in resuming these talks, and it is reasonable to assume that hypersonic weapons limitations would be on the agenda.

Constraints on hypersonic weapons could also feature in any future U.S.-Russian discussion of strategic arms limitations. Under an ideal scenario, the two sides would agree to extend New START before it expires and then commence discussions on a successor agreement, one that would allow for advances in technology, such as the introduction of hypersonic weapons. Presumably, such talks would begin on a bilateral basis, but ideally China would be invited and would agree to join.

Achieving an outright ban on hypersonic weapons may not be a realistic outcome of such discussions, but it might be possible to consider limitations on how hypersonic weapons can be armed, positioned, and employed. The intent here would not be to proscribe the deployment of hypersonic weapons, but rather to prevent their use in ways that would facilitate the rapid escalation of conflict or the early use of nuclear weapons. The need for such measures has already been voiced by congressional refusal to fund conventionally armed strategic missiles.18 This has reduced some of the hypersonic risks, but not all. Still worrisome is the risk of ambiguity about the intent of attack and the entanglement problem. To address these concerns, other measures are needed.

One solution would be to preserve the INF Treaty or, if this is a lost cause, commence Chinese-Russian-U.S. negotiations on a new agreement to cover intermediate-range weapons of the sort now being developed by all three countries. Such an agreement could, like the soon-to-expire INF Treaty, prohibit all weapons of a certain type and range or set limits on the numbers and capabilities of any weapons that are deployed. One approach would be to set a limit on all deployed hypersonic weapons, whether air, sea, or ground launched. Another would be to limit their deployed numbers below a certain threshold, which would eliminate fears of a disarming first strike. Until such negotiations can be undertaken or while they are under way, the three powers should consider confidence-building measures aimed at reducing the risk of unintended escalation. Such measures could include information-sharing on the range and capabilities of proposed weapons and protocols intended to differentiate conventionally armed hypersonic weapons from nuclear-armed ones, so as to reduce the risk of warhead ambiguity.19

Admittedly, such negotiations seem distant, so Congress should intervene and impose its own speed bumps on the rush to deploy hypersonic weapons. In contrast to the measured pace of hypersonics development in the past, the Pentagon is rushing ahead with the design and testing of these weapons without careful thought to their strategic implications or escalation consequences.

“The development of hypersonic weapons in the United States,” argues Acton, “has been largely motivated by technology, not by strategy. In other words, technologists have decided to try and develop hypersonic weapons because it seems like they should be useful for something, not because there is a clearly defined mission need for them to fulfill.”20

Before Congress approves the funds the Pentagon is seeking for hypersonic weaponry, it should ask, What are these munitions needed for? Do they pose an unnecessary risk of escalation? Are there better alternatives?

The Defense Department will argue that it needs to ensure U.S. leadership in the burgeoning hypersonic arms race with China and Russia, but higher spending on predominantly offensive weapons does nothing to protect the United States from similar advances by its competitors. In fact, such spending might put the United States at greater risk by inducing adversaries to accelerate their own offensive programs. It is very difficult to defend against hypersonic weapons. The only sure way to protect the United States and its forces abroad from hypersonic weapons is to restrain them through arms control agreements.

ENDNOTES

1. On the arms control implications of hypersonics, see Amy F. Woolf, “Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long-Range Ballistic Missiles: Background and Issues,” CRS Report, R41464, January 8, 2019.

2. For background on hypersonic weapons and their characteristics, see Richard H. Speier et al., “Hypersonic Missile Proliferation: Hindering the Spread of a New Class of Weapons,” RAND Corp., 2017, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2100/RR2137/RAND_RR2137.pdf.

3. Woolf, “Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long-Range Ballistic Missiles,” p. 6.

4. See Paul McLeary, “PACOM Harris: U.S. Needs to Develop Hypersonic Weapons,” USNI News, February 14, 2018, https://news.usni.org/2018/02/14/pacom-harris-u-s-needs-develop-hypersonic-weapons-criticizes-self-limiting-missile-treaties.

5. Ankit Panda, “China's Hypersonic Weapon Ambitions March Ahead,” The Diplomat, January 8, 2018.

6. For background on the Avangard system, see Michael Kofman, “Russia’s Avangard Hypersonic Boost-Glide System,” Russia Military Analysis, January 11, 2019, https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/2019/01/11/russias-avangard-hypersonic-boost-glide-system/.

7. Anton Troianovski and Paul Sonne, “Russia Is Poised to Add a New Hypersonic Warhead to Its Arsenal,” The Washington Post, December 26, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/russia-is-poised-to-add-a-new-hypersonic-nuclear-warhead-to-its-arsenal/2018/12/26/e9b89374-0934-11e9-8942-0ef442e59094_story.html.

8. See David Axe, “Is Kinzhal, Russia’s New Hypersonic Missile, a Game Changer?” Daily Beast, March 15, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/is-kinzhal-russias-new-hypersonic-missile-a-game-changer.

9. Corey Dickstein, “Military Services to Work Together to Speed Hypersonic Weapon Development,” Stars and Stripes, July 25, 2018, https://www.stripes.com/news/military-services-to-work-together-to-speed-hypersonic-weapon-development-1.539431.

10. See James M. Acton, “Hypersonic Weapons Explainer,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), April 2, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/04/02/hypersonic-weapons-explainer-pub-75957.

11. Aaron Gregg, “Military-Industrial Complex Finds a Growth Market in Hypersonic Weaponry,” The Washington Post, December 31, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/12/21/military-industrial-complex-finds-growth-market-hypersonic-weaponry/.

12. Peter Erbland, “Tactical Boost Glide (TBG),” Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, n.d., https://www.darpa.mil/program/tactical-boost-glide.

13. James M. Acton, “Silver Bullet? Asking the Right Questions About Conventional Prompt Global Strike,” CEIP, 2014, pp. 113–119, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/cpgs.pdf.

15. See Troy Rummler, “Future Hypersonics Could Be Artificially Intelligent,” Sandia Lab News, April 25, 2019, https://www.sandia.gov/news/publications/labnews/articles/2019/04-26/hypersonics.html.

16. Paul Scharre, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), p. 229.

17. Mark Gubrud, “Test Ban for Hypersonic Missiles?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 6, 2015, https://thebulletin.org/roundtable/test-ban-for-hypersonic-missiles/.

18. For a history of congressional action on hypersonics, see Woolf, “Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long-Range Ballistic Missiles,” pp. 22–32.

19. Acton, “Silver Bullet?” pp. 134–138 and 142–144.

20. Acton, “Hypersonics Weapons Explainer.”

Michael T. Klare is a professor emeritus of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association. This is the third in the “Arms Control Tomorrow” series, in which he considers disruptive emerging technologies and their implications for war-fighting and arms control.

NPT states-parties convened at the United Nations from April 29 to May 10 for the final preparatory committee meeting for the 2020 review conference. They agreed by an unusual mechanism to designate veteran Argentine diplomat Rafael Mariano Grossi as president of the review conference, effective in the last quarter of 2019. The decision empowers Grossi to begin immediate consultations with NPT member states to prepare for the potentially contentious review conference. Grossi is Argentina’s permanent representative to international organizations in Vienna, including the International Atomic Energy Agency, where he previously served as assistant director-general for policy.

NPT states-parties convened at the United Nations from April 29 to May 10 for the final preparatory committee meeting for the 2020 review conference. They agreed by an unusual mechanism to designate veteran Argentine diplomat Rafael Mariano Grossi as president of the review conference, effective in the last quarter of 2019. The decision empowers Grossi to begin immediate consultations with NPT member states to prepare for the potentially contentious review conference. Grossi is Argentina’s permanent representative to international organizations in Vienna, including the International Atomic Energy Agency, where he previously served as assistant director-general for policy. I see value in having this conversation, which has political significance. These people may be part of national delegations, and they should have a say in the sort of commitments, in the sort of compromise building that I am trying to strengthen at this moment. Later on will be a time for diplomatic negotiations and small groups and draftings and all of that, but you have to prepare the ground for that by trying to have this sort of wider conversation.

I see value in having this conversation, which has political significance. These people may be part of national delegations, and they should have a say in the sort of commitments, in the sort of compromise building that I am trying to strengthen at this moment. Later on will be a time for diplomatic negotiations and small groups and draftings and all of that, but you have to prepare the ground for that by trying to have this sort of wider conversation. nd inclinations, we have a mandate to conduct a full review, and this is what I’m going to do. I’m aware of viewpoints and analyses, some of them very interesting, that suggest that it would be better for me to try to cut corners and save ourselves the aggravation of discussions that some consider pointless by trying to go straight for a minimalistic sort of outcome: We agree to disagree, then go home.

nd inclinations, we have a mandate to conduct a full review, and this is what I’m going to do. I’m aware of viewpoints and analyses, some of them very interesting, that suggest that it would be better for me to try to cut corners and save ourselves the aggravation of discussions that some consider pointless by trying to go straight for a minimalistic sort of outcome: We agree to disagree, then go home. The video’s existence raised concerns that the group was seeking to acquire materials for a primitive nuclear device or a dirty bomb. Was there a plan to abduct the official and ransom him for nuclear or radioactive materials or to bribe or coerce the official to turn him into an unwilling insider?

The video’s existence raised concerns that the group was seeking to acquire materials for a primitive nuclear device or a dirty bomb. Was there a plan to abduct the official and ransom him for nuclear or radioactive materials or to bribe or coerce the official to turn him into an unwilling insider? First, the review conference is the only legally mandated forum for enduring nuclear security dialogue. ICONS, which is approved by IAEA member states in an annual nuclear security resolution, was first held in 2013 and is currently on a three- or four-year cycle. Although ICONS covers a range of nuclear security-related topics and informs the work of the IAEA in the area of nuclear security, it is not based on a concrete set of legal obligations. The point of contact meetings, while also useful technical meetings, are not specifically mandated under the treaty and have only been convened since 2016. The legal basis for the review conference provides a stronger mandate for sustained dialogue on nuclear security and greater durability than other conferences and meetings that rely on the continued interest and resources of IAEA member states.

First, the review conference is the only legally mandated forum for enduring nuclear security dialogue. ICONS, which is approved by IAEA member states in an annual nuclear security resolution, was first held in 2013 and is currently on a three- or four-year cycle. Although ICONS covers a range of nuclear security-related topics and informs the work of the IAEA in the area of nuclear security, it is not based on a concrete set of legal obligations. The point of contact meetings, while also useful technical meetings, are not specifically mandated under the treaty and have only been convened since 2016. The legal basis for the review conference provides a stronger mandate for sustained dialogue on nuclear security and greater durability than other conferences and meetings that rely on the continued interest and resources of IAEA member states. President Nixon’s approval was both an honor and a media albatross around Lugar’s neck. He appeared to accept both with equanimity. Lugar was, at heart, a moderate conservative. Both words were important, and the arms control community would ignore the second one at its peril.

President Nixon’s approval was both an honor and a media albatross around Lugar’s neck. He appeared to accept both with equanimity. Lugar was, at heart, a moderate conservative. Both words were important, and the arms control community would ignore the second one at its peril. When the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty was sent to the Senate in 2010, Lugar became its chief Republican supporter. Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry (D-Mass.) and he worked closely together to ensure that the committee’s hearings featured Republican witnesses and military officers who had been promoted to their positions by President George W. Bush. Lugar obtained changes in the proposed resolution of advice and consent that addressed many issues raised by treaty skeptics, and even treaty opponents had to admit that the resolution went the extra mile to meet their concerns. The treaty’s fate remained in doubt almost until the day that floor debate began, however, and while people rightly credit Kerry for being willing to roll the dice, Lugar’s steady support for holding that floor debate and vote during a lame duck session was vital to the treaty’s success.

When the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty was sent to the Senate in 2010, Lugar became its chief Republican supporter. Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry (D-Mass.) and he worked closely together to ensure that the committee’s hearings featured Republican witnesses and military officers who had been promoted to their positions by President George W. Bush. Lugar obtained changes in the proposed resolution of advice and consent that addressed many issues raised by treaty skeptics, and even treaty opponents had to admit that the resolution went the extra mile to meet their concerns. The treaty’s fate remained in doubt almost until the day that floor debate began, however, and while people rightly credit Kerry for being willing to roll the dice, Lugar’s steady support for holding that floor debate and vote during a lame duck session was vital to the treaty’s success. For me personally, it’s a given that this also means that even today, we have to cultivate a dialogue with Russia, even though Russia is making no secret of the fact that it’s building up its nuclear and conventional arsenal, as well as, increasingly, its cyber capabilities.

For me personally, it’s a given that this also means that even today, we have to cultivate a dialogue with Russia, even though Russia is making no secret of the fact that it’s building up its nuclear and conventional arsenal, as well as, increasingly, its cyber capabilities. A decision on whether to extend New START is one that President Donald Trump “will make at some point next year,” said Tim Morrison, senior director for weapons of mass destruction and biodefense at the National Security Council, in May 29 remarks at the Hudson Institute in Washington.

A decision on whether to extend New START is one that President Donald Trump “will make at some point next year,” said Tim Morrison, senior director for weapons of mass destruction and biodefense at the National Security Council, in May 29 remarks at the Hudson Institute in Washington. The announcement came exactly one year after the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and began to reimpose sanctions that were lifted as part of the agreement. Over the past year, U.S. President Donald Trump and other administration officials have escalated their use of bellicose language as they implement their strategy of “maximum pressure” on Iran.

The announcement came exactly one year after the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and began to reimpose sanctions that were lifted as part of the agreement. Over the past year, U.S. President Donald Trump and other administration officials have escalated their use of bellicose language as they implement their strategy of “maximum pressure” on Iran. North Korea’s May 4 flight test of the new mobile missile marked the country’s first ballistic missile launch since it tested an intercontinental ballistic missile in November 2017. (

North Korea’s May 4 flight test of the new mobile missile marked the country’s first ballistic missile launch since it tested an intercontinental ballistic missile in November 2017. ( The decision to resume missile testing without breaching the April 2018 moratorium may also have been designed to demonstrate that Kim’s ultimatum for negotiations is serious. Kim said in April that the United States must change its negotiating approach by the end of the year or face a “bleak and very dangerous” situation. Specifically, he called on the United States to pursue a new “methodology” for talks, likely a reference to North Korea’s rejection of the Trump administration’s preference for a comprehensive deal. (

The decision to resume missile testing without breaching the April 2018 moratorium may also have been designed to demonstrate that Kim’s ultimatum for negotiations is serious. Kim said in April that the United States must change its negotiating approach by the end of the year or face a “bleak and very dangerous” situation. Specifically, he called on the United States to pursue a new “methodology” for talks, likely a reference to North Korea’s rejection of the Trump administration’s preference for a comprehensive deal. ( The debate highlighted the nonproliferation crisis in Iran, which announced midway through the meeting that it would cease to abide by some of the restrictions imposed by the 2015 multilateral nuclear deal formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Iran’s announcement came one year after the United States withdrew from the deal and after recent U.S. moves to reimpose sanctions waived by the deal and to levy additional punitive measures. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani warned that Iran could take retaliatory measures in 60 days should the remaining five parties to the JCPOA fail to thwart U.S. sanctions on Tehran’s oil and banking transactions.

The debate highlighted the nonproliferation crisis in Iran, which announced midway through the meeting that it would cease to abide by some of the restrictions imposed by the 2015 multilateral nuclear deal formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Iran’s announcement came one year after the United States withdrew from the deal and after recent U.S. moves to reimpose sanctions waived by the deal and to levy additional punitive measures. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani warned that Iran could take retaliatory measures in 60 days should the remaining five parties to the JCPOA fail to thwart U.S. sanctions on Tehran’s oil and banking transactions.