June 2020

By Sharon K. Weiner

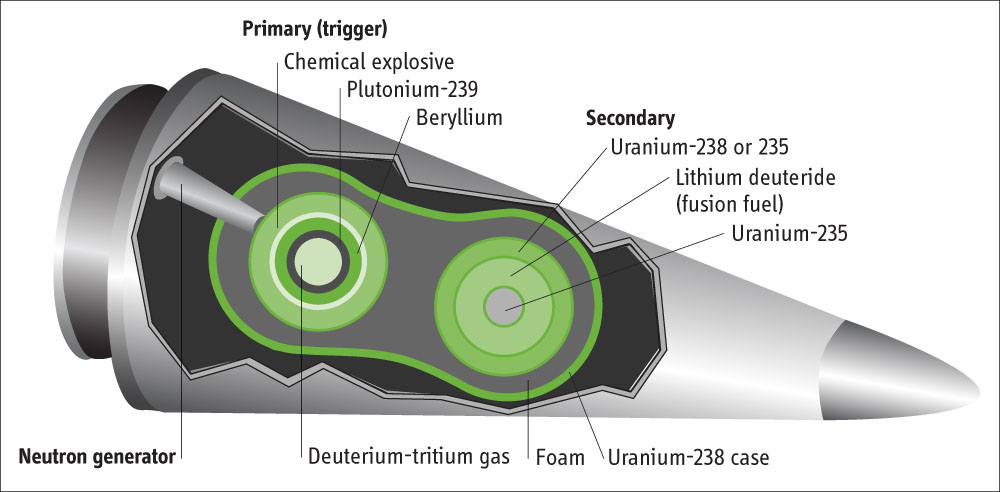

U.S. efforts to produce and maintain the plutonium cores of its nuclear weapons have endured a troubled history of safety and environmental problems since the first plutonium was produced in Hanford, Washington, in 1944. These hollow metal cores, each weighing several kilograms, enable the initial, explosive chain reaction in nuclear weapons.1 The last pit production facility at Rocky Flats was closed in 1989 due to widespread contamination and negligence. In the 1990s, pit production essentially stopped as arsenals declined. Although pit production was eventually relocated to Los Alamos National Laboratory, the lab struggled to produce more than a handful, if any, pits in any given year.

Yet, pit production ambitions persisted. The Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plans gave impetus to a variety of schemes and in the fiscal year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress required the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the semiautonomous nuclear weapons agency of the Department of Energy, to build a facility that could demonstrate an annual production capacity of 80 pits. Although several plans for such a facility at Los Alamos were proposed, each was postponed or abandoned because of unclear justifications, budget shortfalls, or both.

Yet, pit production ambitions persisted. The Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plans gave impetus to a variety of schemes and in the fiscal year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress required the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the semiautonomous nuclear weapons agency of the Department of Energy, to build a facility that could demonstrate an annual production capacity of 80 pits. Although several plans for such a facility at Los Alamos were proposed, each was postponed or abandoned because of unclear justifications, budget shortfalls, or both.

Under the Trump administration, pit production efforts have enjoyed new momentum. In 2019, Congress set the requirement not only to demonstrate capacity but to produce at least 80 pits per year by 2030. The administration also made pit production a budget priority. The Energy Department’s fiscal year 2021 budget request asks for about $1.4 billion to support plans for production of new plutonium pits, a massive increase of $570 million over the fiscal year 2020 appropriated level. The NNSA plans to build two pit production facilities: one at Los Alamos and a second, larger facility in South Carolina at the Savannah River Site.

Pit production, however, is not the requirement it is claimed to be. Current pit production plans are likely to cost significantly more than estimated, putting increased pressure on an already strained federal budget. Moreover, assessing the underlying assumptions makes clear there are credible alternatives to the scale and planned start date for pit production. Additionally, current plans and their latent potential to ramp up to larger pit production rates raise concerns that the United States is also interested in developing new types of nuclear weapons and expanding the arsenal. This may well feed the potential for an arms race with Russia or China and will also undermine long-standing U.S. commitments to arms control and to a reduction in reliance on nuclear weapons.

Cost and Schedule Problems (Again)

To meet the production goal of 80 pits by 2030, the NNSA intends for Los Alamos to make 30 pits per year, with the rest to be produced at the Savannah River Site. According to a January 2019 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, the estimated cost of NNSA pit production plans are $9 billion over the next decade.2 Yet, past performance and multiple independent assessments raise questions about the ability of the NNSA to deliver on time and within budget.

One set of concerns involves the facilities at Los Alamos. Since the closure of Rocky Flats, Los Alamos has led the charge for reconstituting pit production despite numerous setbacks to its plans and facilities. Its Plutonium Facility Building 4 (PF-4), the site of current pit production activities, is supposed to install a production capacity of 10 pits per year and then ramp up to a capability of making 30 pits per year by 2026, but the facility may not be up to the task. Los Alamos produced only five prototype pits in fiscal year 2019, which are not the “war reserve” pits that meet that standards for deployment on nuclear weapons. PF-4 is seeking to be able to produce its first such pit in 2023.

Designed in the 1970s, PF-4 lacks important safety features and has a history of safety problems. For example, in 2013, Los Alamos paused work at PF-4 for three years after the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board noted a variety of ongoing problems, including violations of rules intended to ensure the safe storage of plutonium. According to safety experts, Los Alamos lacked enough personnel “who knew how to handle plutonium so it didn’t accidentally go ‘critical’ and start an uncontrolled chain reaction.”3 In 2016 the lab had to cancel its plans to resume work at PF-4 because of concerns over safety. The lab also has repeatedly been criticized for lacking plans to mitigate risks from local forest fires and seismic activity, even though concerns about both have increased in recent years. Although pit work resumed in 2017, the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board documented problems with delayed and incomplete upgrades to safety controls.4 Add in broader problems with the safety culture at Los Alamos, and this suggests that accidents will remain a concern.

PF-4 is also crowded because of its other plutonium missions. In addition to pit production, the facility converts excess weapons-grade plutonium into plutonium dioxide in preparation for its storage or disposition. It also supports NASA by processing plutonium-238, which is used as an energy source for space missions. Yet, there are limits on how much plutonium can be in an area at any one time. It is not clear that PF-4 can expand pit production without shortchanging disposition activities or NASA or violating safety standards.

Los Alamos’s planning of pit-related facilities has also been problematic. Technical analysis on pit sample material was to be performed at a new Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement-Nuclear Facility. That project was terminated in 2014 after significant cost overruns and a failure to meet environmental regulations for the handling and disposal of nuclear waste. The Radiological Laboratory Utility Office Building, which provides facilities for a variety of activities related to plutonium work, was completed in 2010, but had a leak in its radioactive waste system in 2019. Prior to current pit production plans, the NNSA was criticized for pushing the adoption of Los Alamos’s “modular” plan to increase space for plutonium work without adequate analysis of the risk of failure, alternatives, or cost.5

The military’s frustration with Los Alamos’s repeated failures is rumored to be behind the addition of a second pit production facility. This larger facility, the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility (SRPPF), is intended make 50 pits per year. The SRPPF will be housed in a repurposed building that was to have been the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility, originally intended to convert excess weapons-grade plutonium into nuclear reactor fuel. The NNSA was finally persuaded to cancel the mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel project in 2018 after its original cost of $1.6 billion ballooned to potentially more than $100 billion.6 Left behind was an unfinished concrete shell primed for plutonium work. In 2018 the building was estimated to be about 70 percent complete. About one-quarter of this construction, however, needed to be redone because of improper installation, failure to meet required regulations, and a host of other problems.7 It is unclear what other problems may arise in trying to turn this incomplete building into a pit production facility.

Independent analysis has called into question the NNSA’s ability to meet pit production requirements at Los Alamos and Savannah River. A 2019 assessment found that although redundant facilities would provide a buffer against natural disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or fires, or geopolitical developments leading to a more hostile international environment, neither Los Alamos nor the SRPPF could alone produce 80 pits per year.8 The assessment also concluded that because the NNSA has difficulties managing large projects, it is very risky to assume current pit production plans will be finished on schedule and without significant cost overruns.

Any pit manufacturing facility is likely to take significantly longer than anticipated, cost much more than planned, and require significant revisions to succeed. These problems may not be amenable to a better management solution. They reflect what has been identified as a larger, enduring problem at the NNSA and the Energy Department. Despite years of trying to improve project management, the NNSA remains on the Government Accountability Office’s list of government organizations that are at high risk of “fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement” due to its track record and current practices.9

Even if current plans succeed, other complications flow from the redundancies built into them. The 2019 NDAA requires Los Alamos to make plans to produce up to 80 pits per year on its own, in the event that the SRPPF is not ready in time.10 Additionally, the SRPPF is a large facility that could make 80 pits per year or more on its own.11 The potential redundancy built into the twin pit production projects could lead to an effective capacity to produce at least 160 pits per year.

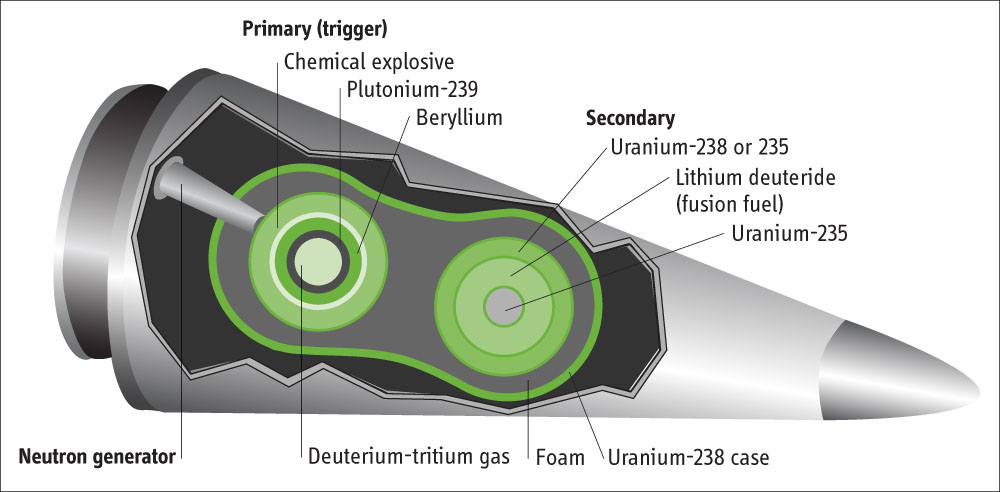

There are political risks to this redundancy. Domestically, pit production has raised concerns about the ability of Los Alamos and the Savannah River Site to ensure environmental safety. Los Alamos, for example, is on or near several known earthquake faults, and the Savannah River Site is vulnerable to wind and flood damage from hurricanes. The politics of “not in my backyard” are also significant. South Carolina, for example, sued the Energy Department for failing to meet its promise of removing all plutonium from the state. Further, pit production at the Savannah River Site will require moving more plutonium across the United States. Instead of shipping pits some 300 miles from their current storage site at the Pantex Plant in Texas to Los Alamos, they will travel almost 1,000 additional miles to get to the Savannah River Site.

Internationally, the plan raises concerns that the United States may be interested in expanding its nuclear arsenal with many more weapons or a large number of warheads with new capabilities. At a rate of 160 pits per year, the United States in less than three years would be able to build as many new nuclear weapons as are believed to be in China’s current arsenal. The uncertain future of the U.S.-Russian New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which limits each country to 1,550 deployed strategic warheads, is a particular concern. That agreement is set to expire in 2021, and the Trump administration has resisted efforts to work toward a five-year extension. If the treaty expires with nothing to replace it, there will be no legally binding limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals for the first time in half a century.

The Argument for 80

The NNSA provides two main justifications for creating an 80-pit-per-year production capability by 2030. One rests on assumptions about pit aging, and the other on enhancing warhead safety.

The most frequent argument in support of pit production focuses on size of the U.S. stockpile as warheads age. The current U.S. arsenal is estimated to include about 3,800 warheads, of which 1,750 are currently deployed and the remainder are in a reserve in various stages of readiness.12 The pits for these warheads were all manufactured between 1979 and 1990. Even though all warheads that will remain in the arsenal are scheduled to undergo life extension programs (LEPs), current plans assume that all of these pits must be replaced before they reach an age past which they might no longer work reliably due to problems with corrosion or plutonium decay. As explained by Peter Fanta, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear matters late last year, “Want to know where 80 pits per year came from? It’s math. Alright? It’s really simple math. Divide 80 per year by the number of active warheads we have—last time it was unclassified it was just under 4,000—and you get a timeframe.”13

How old is too old for a pit? In the early 2000s when the NNSA was considering building a capacity for producing between 125 and 450 pits per year, the weapons labs argued that pits will perform as designed for 45 to 60 years.14 In 2006 that estimate was significantly increased based on a series of studies at the weapons labs, plus an external evaluation by JASON, an independent group of scientists who consult on technical matters related to national security. According to the JASON study, “[m]ost primary types have credible minimum lifetimes in excess of 100 years as regards aging of plutonium; those with assessed minimum lifetimes of 100 years or less have clear mitigation paths that are proposed and/or being implemented.”15 A 2012 assessment by the weapons lab at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory went even further, putting pit lifetimes at 150 years.16 In 2019, a few months after the NNSA took over the funding contract for JASON research from the Department of Defense, the group issued a letter explaining that “the present assessments of aging do not indicate any impending issues for the stockpile” but implying discomfort with pits beyond 80 years old and supporting the “expeditious” reestablishment of a pit production capacity because “a significant period of time will be required to recreate the facilities and expertise” needed to manufacture plutonium pits.17

Under the conservative estimate of 100 years of pit life before replacement, the youngest pits in the stockpile today will age out in 2090. If pit production begins in 2030, that would require 63 pits per year in order to replace all pits before the last one reaches 100 years of age sometime in 2090. At the rate of 80 pits per year, pit production need not begin until 2042 (table 1).

Another variable is the size of the nuclear arsenal. As part of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the military agreed that it could meet its deterrence and war-fighting requirements with about 1,000 deployed nuclear weapons.18 Each of those 1,000 deployed weapons having a backup in the stockpile would result in an overall arsenal size of 2,000 warheads, rather than the 3,800 warheads today, which relaxes even further the requirements for pit production. Assuming pits age out after 100 years, a requirement to replace all 2,000 warheads could be met by producing 33 pits per year starting in 2030 or by producing 80 pits per year starting in 2065. The arguments for pit production starting in 2030 or for 80 pits per year appear to be choices rather than requirements (table 1).

Another variable is the size of the nuclear arsenal. As part of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the military agreed that it could meet its deterrence and war-fighting requirements with about 1,000 deployed nuclear weapons.18 Each of those 1,000 deployed weapons having a backup in the stockpile would result in an overall arsenal size of 2,000 warheads, rather than the 3,800 warheads today, which relaxes even further the requirements for pit production. Assuming pits age out after 100 years, a requirement to replace all 2,000 warheads could be met by producing 33 pits per year starting in 2030 or by producing 80 pits per year starting in 2065. The arguments for pit production starting in 2030 or for 80 pits per year appear to be choices rather than requirements (table 1).

Rather than assumptions about plutonium aging, it appears that the push to begin pit production by 2030 is based on plans for the newly designed W87-1 warhead and arguments about the need for enhanced warhead safety features.19 All warhead pits are encased in an explosive shell that surrounds the pit and compresses it to begin the chain reaction that produces the explosion. Three warheads currently use conventional high explosive (CHE): the W88 and W76 warheads on submarines and the W78 warhead on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Moving to insensitive high explosive (IHE), which is less vulnerable to shock and heat, would lower the risk for accidents that could lead to the dispersal of plutonium. Because a greater weight and volume of IHE is required to drive compression in a primary, for some warhead types a shift to IHE may require a different pit design and thus the manufacture of new pits.20

The Navy has long argued that it prefers its own warheads even if they contain CHE. Shifting to IHE would have implications for missile range and the design of reentry vehicles.21 Naval resistance is one of the reasons for the demise of plans for an interoperable warhead, a suite of three new warhead designs proposed under the Obama administration that would have allowed the same IHE warhead to fit on Navy and Air Force ballistic missiles. Similarly, the Navy opted to “refresh” the CHE on the W88 rather than redesign warheads and missiles. The close quarters on a submarine, plus the periodic removal of missiles and refit of the submarine, would presumably make the Navy especially sensitive about warhead safety. Unlike the Air Force, the Navy has never had an accident that led to the dispersal of plutonium. The Navy’s safety record, plus its resistance to opting for IHE-based warheads, calls into question the merits of NNSA arguments about the need to redesign warheads and make new pits in order to increase safety.

The Air Force, which operates land-based ICBMs and has had plutonium-dispersal accidents, prefers warheads with IHE. The NNSA and the Air Force have approved replacing the W78, which contains CHE, with a new warhead named the W87-1 because it is based on the design of the W87-0, the other ICBM warhead, which already uses IHE.22 Once completed, all ICBM warheads would contain IHE. According to the NNSA, the new W87-1 is to be in place by fiscal year 2030, in time to arm the next-generation ICBM, the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), which is optimistically slated for deployment starting in 2029 and lasting through 2036.23 Meeting this eight-year schedule requires the capability to produce on average 75 pits per year if the estimated 600 W78s in the current arsenal are all replaced with the new W87-1 by the time all the new GBSD missiles are deployed.24 To be ready in time, the NNSA argues that the United States has to begin building a pit production facility now, partially because it may take as long as 15 years to bring any new pit production facility into operation.25

There are several reasons why 2030 is still not a hard start date for pit production. The schedule for the GBSD program may slip; delays are not uncommon in major acquisition programs. More significantly, instead of making a new warhead, the Air Force could replace any problematic W78 warheads with W87-0 warheads. The W87-0 completed an LEP in 2004. This gave additional shelf life to the estimated 200 such warheads already deployed on Minuteman III missiles. Plus, there are believed to be enough extra W87-0 warheads in the stockpile to replace the 200 deployed W78 warheads and even have spares left over.26 The NNSA has argued that fear of a failure in an entire class of warheads means it is prudent to have at least two different designs for each delivery system. Plans to replace the W78 with a warhead based on the design of the other ICBM warhead, however, suggest there is room for compromise.

Even if all ICBMs are not outfitted with the W87, the W78 likely still has some life left, even though it is the oldest warhead in the arsenal. Manufactured between 1979 and 1982, the pits in these warheads have at least another 40 years of life before they may need to be replaced.

Pits at Any Price

Irrespective of production numbers and start date, both the NNSA and U.S. Strategic Command have stated that pit production is one of their highest priorities. Their justifications, however, are derived from ambiguous evidence that suggest judgment calls shaped by institutional self-interest rather than strict technical requirements.

One argument is that pit production is necessary as a hedge against the unexpected discovery of a problem that may affect an entire class of warheads. Details about such “significant findings” that might suggest issues that could mandate replacing an entire class of warheads are classified. In 1996 the General Accounting Office reported that from 1958 to 1996, there were about 1,200 significant findings of which less than 200 identified failures in some component of a weapon system.27 Unknown is how many of these problems were associated with pits. In 2001 the Energy Department’s inspector general provided an update, stating that “[s]ince 1958, more than 1200 significant findings have been identified. About 120 findings have resulted in retrofits or major design changes to the nuclear weapons stockpile.”28 Although five years had passed since the 1996 report, it seems that the number of significant findings was largely unchanged. This should suggest confidence in the Stockpile Stewardship Program rather than plans to replace all pits.

One argument is that pit production is necessary as a hedge against the unexpected discovery of a problem that may affect an entire class of warheads. Details about such “significant findings” that might suggest issues that could mandate replacing an entire class of warheads are classified. In 1996 the General Accounting Office reported that from 1958 to 1996, there were about 1,200 significant findings of which less than 200 identified failures in some component of a weapon system.27 Unknown is how many of these problems were associated with pits. In 2001 the Energy Department’s inspector general provided an update, stating that “[s]ince 1958, more than 1200 significant findings have been identified. About 120 findings have resulted in retrofits or major design changes to the nuclear weapons stockpile.”28 Although five years had passed since the 1996 report, it seems that the number of significant findings was largely unchanged. This should suggest confidence in the Stockpile Stewardship Program rather than plans to replace all pits.

More reasons to question the need for pit production can be found in the results of warhead surveillance testing since 2001 (table 2). Even with a robust testing schedule, the number of findings that required modifications to some part of the warhead has declined over time and remains at or near zero. Moreover, according to the NNSA, some significant findings can be mitigated in ways that do not require a new pit.29

The 30-year absence of pit production capability, plus the focus on warhead LEPs instead of replacement, suggest major unexpected problems seldom or never appear. Additionally, if a technical problem goes undetected for decades but suddenly calls into question the functionality of an entire class of warheads, there are enough spares in the active and reserve stockpiles to replace those warheads or provide additional deployed warheads on other delivery systems.

The NNSA has argued that warheads need to function “as designed.”30 The nuclear weapons research and design labs have also made the case that new designs are necessary in order to maintain a cadre of experts in weapons design. Specialty nuclear weapons for niche functions, such as the mid-2000s proposal for a Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator, have also been a driver. Collectively, these justifications raise concerns that conservative assumptions about pit age and replacement are at least partially a function of concern for jobs and future missions.

Another area that is open to interpretation is the relationship between pit age and military requirements. Military requirements focus on the degree of certainty that a nuclear weapon will launch, arrive, and explode as planned within a defined range of planned parameters. Military requirements are also classified, but it is not clear that a warhead’s ability to meet requirements drops precipitously once it reaches a certain age. Further, it may be possible to relax requirements or modify delivery systems in other ways without jeopardizing the deterrent value of nuclear weapons. For example, in 2016 the Nuclear Weapons Council authorized an increase in the amount of tritium in U.S. nuclear weapons because of concerns about performance reliability.31

Another area that is open to interpretation is the relationship between pit age and military requirements. Military requirements focus on the degree of certainty that a nuclear weapon will launch, arrive, and explode as planned within a defined range of planned parameters. Military requirements are also classified, but it is not clear that a warhead’s ability to meet requirements drops precipitously once it reaches a certain age. Further, it may be possible to relax requirements or modify delivery systems in other ways without jeopardizing the deterrent value of nuclear weapons. For example, in 2016 the Nuclear Weapons Council authorized an increase in the amount of tritium in U.S. nuclear weapons because of concerns about performance reliability.31

The current U.S. moratorium on explosive nuclear testing is sometimes offered as a justification for pit production. The Pentagon's “Nuclear Matters Handbook 2020” suggests uncertainties about warhead performance might be addressed by changing warhead designs. According to the Defense Department, “Eventually, all of the weapons in the legacy stockpile will need to be replaced by new warheads whose designs place a premium on yield margin so that they can be certified without the benefit of nuclear explosive testing.”32 Yet instead of setting military requirements for individual components of the warhead, those requirements could apply to the weapon system overall. This would allow for any deficiencies in yield to be compensated by improvements in accuracy or other changes.

Pits and Politics

In assessing the many justifications offered for pit production, Congress has often deferred to the self-interest of a few members. The New Mexico congressional delegation has led the charge for keeping pit production at Los Alamos, but done little to support a more rigorous investigation of environmental safety or oversight of pit production plans.33 Once the MOX fuel project was terminated, Senator Lindsay Graham (R-S.C.) shifted positions to become a staunch supporter of two pit production facilities because one of these sites would be in his state.

Seen more broadly, although justifications largely focus on warhead safety and reliability, pit production plans go beyond what is necessary to replicate current nuclear arsenal capabilities. This, in turn, raises concerns that part of the driver for pit production is an interest in new warhead designs and laying the foundation for a potential expansion of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Both would likely have adverse effects on the global nonproliferation regime and exacerbate tensions with Russia and China.

Pit production is not a policy goal in itself. The ultimate purpose of making pits is not to replace those in the current nuclear arsenal or add to this arsenal. It is to maintain a robust nuclear force and posture that can deter potential adversaries. If nuclear deterrence rather than reproducing the status quo or expanded pit replacement is the goal, current pit production plans are not a requirement but one option of many. Given the likely cost and possible adverse effects of current plans, it is important to reevaluate their underlying assumptions and justifications in order to consider the full range of alternatives.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. Department of Energy, “FY 2021 Congressional Budget Request: National Nuclear Security Administration,” DOE/CF-0161, February 2020, p. 163.

2. Congressional Budget Office, “Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2019 to 2028,” January 2019, p. 5, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-01/54914-NuclearForces.pdf.

3. R. Jeffrey Smith and Patrick Malone, “Safety Problems at a Los Alamos Laboratory Delay U.S. Nuclear Warhead Testing and Production,” Science, June 30, 2017, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/06/safety-problems-los-alamos-laboratory-delay-us-nuclear-warhead-testing-and-production.

4. Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, Letter to Secretary of Energy James Perry, November 15, 2019, https://ehss.energy.gov/deprep/2019/FB19N15B.PDF.

5. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “DOE Project Management: NNSA Needs to Clarify Requirements for Its Plutonium Analysis Project at Los Alamos,” GAO-16-585, August 2016, pp. 23–27.

6. Aerospace Corp., “Plutonium Disposition Study Options Independent Assessment Phase 1 Report,” TOR-2015-01848, April 13, 2015, p. 4.

7. “Plutonium Disposition and the MOX Project,” hearing before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces of the Committee on Armed Services, 114th Cong. (2015).

8. Institute for Defense Analyses, “Independent Assessment of the Two-Site Pit Production Decision: Executive Summary,” May 2019, https://www.ida.org/-/media/feature/publications/i/in/independent-assessment-of-the-two-site-pit-production-decision-executive-summary/d-10711.ashx.

9. GAO, “High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas,” GAO-19-157SP, March 2019, pp. 217–221.

10. John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, Pub. L. No. 115–232, 132 Stat. 1636 (2018), sec. 3120.

11. Colin Demarest, “Study: Savannah River Pit Hub Could Meet National Demand for Nuclear Weapon Cores,” Aiken Standard, April 9, 2020.

12. For stockpile estimates, see Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 76, No. 1 (2020): 46–60.

13. Colin Demarest, “Why 80? Defense Leaders Discuss the Need for Plutonium Pits,” Aiken Standard, December 28, 2019.

14. U.S. Department of Energy, “Draft Supplemental Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on Stockpile Stewardship and Management for a Modern Pit Facility,” DOE/EIS-236-S2, May 2003, p. S-12.

15. R.J. Hemley et al., “Pit Lifetime,” MITRE Corp., JSR-06-335, January 11, 2007, p. 1.

16. Arnie Heller, “Plutonium at 150 Years: Going Strong and Aging Gracefully,” Science and Technology Review, December 2012, pp. 12, 14.

17. JASON, Letter to Todd Caldwell, November 23, 2019, p. 2.

18. U.S. Department of Defense, “Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States Specified in Section 491 of 10 U.S.C.,” June 12, 2013, p. 6.

19. Greg Mello, “U.S. Plutonium Pit Production Plans Advance, With New Requirements,” International Panel on Fissile Materials, December 23, 2019, http://fissilematerials.org/blog/2019/12/us_plutonium_pit_producti_2.html.

20. David Kramer, “Concerns About Aging Plutonium Drive Need for New Weapon Cores,” Physics Today, July 2018, p. 24.

21. Frank N. von Hippel, “The Decision to End U.S. Nuclear Testing,” Arms Control Today, December 2019.

22. GAO, “Nuclear Weapons: NNSA Has Taken Steps to Prepare to Restart a Program to Replace the W78 Warhead Capability,” GAO-19-84, November 2018, p. 3 n.9.

23. Amy F. Woolf, “U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues,” CRS Report, RL33640, January 3, 2020, p. 21.

24. Kristensen and Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2020,” p. 47.

25. Harold M. Agnew et al., “FY 2000 Report to Congress of the Panel to Assess the Reliability, Safety, and Security of the United States Nuclear Stockpile,” February 1, 2001, p. 10.

26. Kristensen and Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2020,” p. 47.

27. Victor S. Rezendes, “Nuclear Weapons: Status of DOE’s Nuclear Stockpile Surveillance Program” (Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Committee on Armed Services, GAO/T-RCED-96-100, March 13, 1996), p. 2.

28. Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Energy, “Management of the Stockpile Surveillance Program’s Significant Finding Investigations,” DOE/IG-0535, December 2001.

29. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), U.S. Department of Energy, “Fiscal Year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan - Biennial Plan Summary: Report to Congress,” October 2018, p. 2–5.

30. U.S. Department of Energy, “Draft Supplemental Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on Stockpile Stewardship and Management for a Modern Pit Facility,” p. S-11.

31. NNSA, “Fiscal Year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan - Biennial Plan Summary,” p. 2–18.

32. Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Matters, U.S. Department of Defense, “Nuclear Matters Handbook 2020,” n.d., p. 254, https://www.acq.osd.mil/ncbdp/nm/nmhb/docs/NMHB2020.pdf.

33. Susan Montoya Bryan, “U.S. Lawmakers From New Mexico Hold Out on Review of Nuke Plan,” U.S. News and World Report, January 13, 2020.

Sharon K. Weiner is an associate professor in the School of International Service at American University. She thanks Frank von Hippel and Zia Mian for their comments in drafting this article.

But President Donald Trump says he would like to work with Russian President Vladimir Putin “to discuss the arms race, which is getting out of control.” Since April 2018, Trump and his advisers have talked about somehow involving China in nuclear arms control yet they have failed to explain how to do so.

But President Donald Trump says he would like to work with Russian President Vladimir Putin “to discuss the arms race, which is getting out of control.” Since April 2018, Trump and his advisers have talked about somehow involving China in nuclear arms control yet they have failed to explain how to do so.

Yet, pit production ambitions persisted. The Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plans gave impetus to a variety of schemes and in the fiscal year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress required the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the semiautonomous nuclear weapons agency of the Department of Energy, to build a facility that could demonstrate an annual production capacity of 80 pits. Although several plans for such a facility at Los Alamos were proposed, each was postponed or abandoned because of unclear justifications, budget shortfalls, or both.

Yet, pit production ambitions persisted. The Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plans gave impetus to a variety of schemes and in the fiscal year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress required the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the semiautonomous nuclear weapons agency of the Department of Energy, to build a facility that could demonstrate an annual production capacity of 80 pits. Although several plans for such a facility at Los Alamos were proposed, each was postponed or abandoned because of unclear justifications, budget shortfalls, or both.

Another variable is the size of the nuclear arsenal. As part of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the military agreed that it could meet its deterrence and war-fighting requirements with about 1,000 deployed nuclear weapons.

Another variable is the size of the nuclear arsenal. As part of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the military agreed that it could meet its deterrence and war-fighting requirements with about 1,000 deployed nuclear weapons. One argument is that pit production is necessary as a hedge against the unexpected discovery of a problem that may affect an entire class of warheads. Details about such “significant findings” that might suggest issues that could mandate replacing an entire class of warheads are classified. In 1996 the General Accounting Office reported that from 1958 to 1996, there were about 1,200 significant findings of which less than 200 identified failures in some component of a weapon system.

One argument is that pit production is necessary as a hedge against the unexpected discovery of a problem that may affect an entire class of warheads. Details about such “significant findings” that might suggest issues that could mandate replacing an entire class of warheads are classified. In 1996 the General Accounting Office reported that from 1958 to 1996, there were about 1,200 significant findings of which less than 200 identified failures in some component of a weapon system. Another area that is open to interpretation is the relationship between pit age and military requirements. Military requirements focus on the degree of certainty that a nuclear weapon will launch, arrive, and explode as planned within a defined range of planned parameters. Military requirements are also classified, but it is not clear that a warhead’s ability to meet requirements drops precipitously once it reaches a certain age. Further, it may be possible to relax requirements or modify delivery systems in other ways without jeopardizing the deterrent value of nuclear weapons. For example, in 2016 the Nuclear Weapons Council authorized an increase in the amount of tritium in U.S. nuclear weapons because of concerns about performance reliability.

Another area that is open to interpretation is the relationship between pit age and military requirements. Military requirements focus on the degree of certainty that a nuclear weapon will launch, arrive, and explode as planned within a defined range of planned parameters. Military requirements are also classified, but it is not clear that a warhead’s ability to meet requirements drops precipitously once it reaches a certain age. Further, it may be possible to relax requirements or modify delivery systems in other ways without jeopardizing the deterrent value of nuclear weapons. For example, in 2016 the Nuclear Weapons Council authorized an increase in the amount of tritium in U.S. nuclear weapons because of concerns about performance reliability. As the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists warned in January of this year, even before the coronavirus pandemic entered the public consciousness, there are two simultaneous, existential threats—climate change and the possibility of nuclear war—that put humanity closer to disaster than ever before since the end of the Second World War. The Bulletin’s Doomsday Clock has been set to just 100 seconds to midnight. Even more importantly, the international community and world leaders have been complacent in the face of this dire state of affairs and have failed to address these two key challenges together and effectively. The trend toward national isolationism and inadequate international cooperation has exacerbated the terrible impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists warned in January of this year, even before the coronavirus pandemic entered the public consciousness, there are two simultaneous, existential threats—climate change and the possibility of nuclear war—that put humanity closer to disaster than ever before since the end of the Second World War. The Bulletin’s Doomsday Clock has been set to just 100 seconds to midnight. Even more importantly, the international community and world leaders have been complacent in the face of this dire state of affairs and have failed to address these two key challenges together and effectively. The trend toward national isolationism and inadequate international cooperation has exacerbated the terrible impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The concrete gain in security achieved by the 2015 multilateral agreement has recklessly been called into question by the U.S. withdrawal. In addition, at least for the time being, the prospect of gradually building trust with Iran has been destroyed, trust that will be necessary to achieve viable solutions to other questions of stability in the Middle East. Instead, U.S. policy has strengthened the conservative and clerical forces in Iran who are opposed to domestic reforms and international engagement.

The concrete gain in security achieved by the 2015 multilateral agreement has recklessly been called into question by the U.S. withdrawal. In addition, at least for the time being, the prospect of gradually building trust with Iran has been destroyed, trust that will be necessary to achieve viable solutions to other questions of stability in the Middle East. Instead, U.S. policy has strengthened the conservative and clerical forces in Iran who are opposed to domestic reforms and international engagement. As its verification-of-destruction role recedes, the OPCW has undertaken additional responsibilities that, for some, were not originally defined during the CWC’s negotiation. For example, the OPCW has increased its counterproliferation efforts by annually inspecting about 240 industrial sites to ensure their peaceful nature. In 2018, a special session of the OPCW Conference of States Parties empowered the OPCW to investigate and identify the perpetrators, organizers, sponsors, or those otherwise involved whenever chemical weapons are used. The agency’s Technical Secretariat is currently working to establish the basis for this investigation and identification team.

As its verification-of-destruction role recedes, the OPCW has undertaken additional responsibilities that, for some, were not originally defined during the CWC’s negotiation. For example, the OPCW has increased its counterproliferation efforts by annually inspecting about 240 industrial sites to ensure their peaceful nature. In 2018, a special session of the OPCW Conference of States Parties empowered the OPCW to investigate and identify the perpetrators, organizers, sponsors, or those otherwise involved whenever chemical weapons are used. The agency’s Technical Secretariat is currently working to establish the basis for this investigation and identification team. Meanwhile, fishing vessels from Baltic nations regularly recover sea-dumped chemical munitions in their nets. Those old chemical weapons do not belong to the nations that recover them—the Baltic countries never produced chemical weapons—but now they must store them or destroy them with little support from the international community. As a result, these discoveries are not reported to the OPCW.

Meanwhile, fishing vessels from Baltic nations regularly recover sea-dumped chemical munitions in their nets. Those old chemical weapons do not belong to the nations that recover them—the Baltic countries never produced chemical weapons—but now they must store them or destroy them with little support from the international community. As a result, these discoveries are not reported to the OPCW. The risks to the environment may be more substantial. A program funded by the European Union called CHEMSEA has investigated the environmental impacts of chemical munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea, detecting at least one chemical agent in one-third of the sediment and sea life samples collected.

The risks to the environment may be more substantial. A program funded by the European Union called CHEMSEA has investigated the environmental impacts of chemical munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea, detecting at least one chemical agent in one-third of the sediment and sea life samples collected.

An outstanding scholar, extraordinary mentor, and a community builder, Martin Malin passed away on April 19. His warmth, humility, and kindness made him more than a colleague and a close friend to many.

An outstanding scholar, extraordinary mentor, and a community builder, Martin Malin passed away on April 19. His warmth, humility, and kindness made him more than a colleague and a close friend to many. In the late 1980s, Fred Kaplan’s book The Wizards of Armageddon was required reading if you hoped to pass your exams in security studies. That book, as its title aptly suggested, focused on the theorists of nuclear deterrence and other “defense intellectuals” whose novel ideas about deterrence helped shape U.S. nuclear strategy during the Cold War. Now a cult classic for nuclear nerds, it was a path-breaking intellectual history of the people and ideas behind the concept of nuclear deterrence.

In the late 1980s, Fred Kaplan’s book The Wizards of Armageddon was required reading if you hoped to pass your exams in security studies. That book, as its title aptly suggested, focused on the theorists of nuclear deterrence and other “defense intellectuals” whose novel ideas about deterrence helped shape U.S. nuclear strategy during the Cold War. Now a cult classic for nuclear nerds, it was a path-breaking intellectual history of the people and ideas behind the concept of nuclear deterrence. Former Defense Secretary William Perry and Tom Collina, director of policy at the Ploughshares Fund, join forces to write a history of U.S. nuclear launch authority policy.

Former Defense Secretary William Perry and Tom Collina, director of policy at the Ploughshares Fund, join forces to write a history of U.S. nuclear launch authority policy. President Donald Trump justified the withdrawal decision on the grounds that Russia was violating the agreement, but he said, “There’s a very good chance we’ll make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together.”

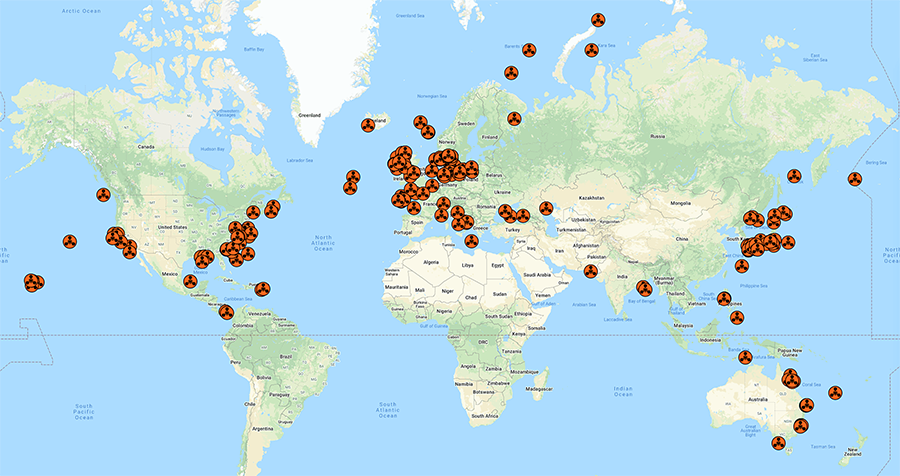

President Donald Trump justified the withdrawal decision on the grounds that Russia was violating the agreement, but he said, “There’s a very good chance we’ll make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together.” “The dangerous and misguided decision to abandon this international agreement cripples our ability to conduct aerial surveillance of Russia, while allowing Russian reconnaissance flights over U.S. bases in Europe to continue,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), who sits on the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees.

“The dangerous and misguided decision to abandon this international agreement cripples our ability to conduct aerial surveillance of Russia, while allowing Russian reconnaissance flights over U.S. bases in Europe to continue,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), who sits on the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees. Marshall Billingslea, whom Trump also has nominated to serve as U.S. undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, said that Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov agreed “to meet, talk about our respective concerns and objectives, and find a way forward to begin negotiations” on a new arms control agreement.

Marshall Billingslea, whom Trump also has nominated to serve as U.S. undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, said that Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov agreed “to meet, talk about our respective concerns and objectives, and find a way forward to begin negotiations” on a new arms control agreement. The recent consideration was taken up by a group of national security officials on May 15, but the participants reportedly did not reach a decision. The idea is “very much an ongoing conversation,” one person familiar with the national security meeting told the Post.

The recent consideration was taken up by a group of national security officials on May 15, but the participants reportedly did not reach a decision. The idea is “very much an ongoing conversation,” one person familiar with the national security meeting told the Post.