June 2022

By Barbara Slavin

Only a few years ago, the notion that Iran could be weeks away from amassing sufficient material for a nuclear weapon would have generated a massive crisis in Washington and monopolized international diplomacy. Yet, there seems to be little palpable sense of urgency today, despite the fact that Iran is enriching uranium to near weapons grade and is on the verge of the proverbial breakout about which Iran hawks have warned so often in the past.1 Meanwhile, negotiations on restoring compliance with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and rolling back Iran’s nuclear advances have been in limbo since mid-March.

In the U.S. view, the ostensible reason for the impasse is an Iranian demand for sanctions relief that goes beyond what is required by the JCPOA. Iran has been seeking removal of the foreign terrorist designation of a powerful branch of the Iranian military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The U.S. Department of State added this designation in 2019 as the Trump administration ran low on new targets to sanction under its “maximum pressure” campaign. The Biden administration, which says it wants to revive the JCPOA, has indicated that it would be willing to lift the designation, which has little practical effect because the IRGC remains subject to numerous other U.S. sanctions, if Iran makes a gesture of its own.2

In the U.S. view, the ostensible reason for the impasse is an Iranian demand for sanctions relief that goes beyond what is required by the JCPOA. Iran has been seeking removal of the foreign terrorist designation of a powerful branch of the Iranian military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The U.S. Department of State added this designation in 2019 as the Trump administration ran low on new targets to sanction under its “maximum pressure” campaign. The Biden administration, which says it wants to revive the JCPOA, has indicated that it would be willing to lift the designation, which has little practical effect because the IRGC remains subject to numerous other U.S. sanctions, if Iran makes a gesture of its own.2

That could entail an Iranian promise to engage in follow-on talks on regional issues or a pledge not to try to kill former U.S. officials implicated in the 2020 assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, head of the Qods Force branch of the IRGC.3 Iran has refused so far, although efforts to find a mutually acceptable compromise continue.

In many ways, the issue appears to be an excuse and not the real cause for the diplomatic deadlock. Other factors have led to the delay in restoring compliance with the JCPOA, in particular, the war in Ukraine. With Russian forces committing atrocities daily in Ukraine and the Western world focused on punishing Russia and rearming the Ukrainians, there is less political bandwidth left to deal with the Iran issue.

The merits of restoring the JCPOA also have come under increasing scrutiny in the United States and Iran. The landmark deal, intended to contain Iran’s nuclear ambitions and to reintegrate Iran into the global economy, never fulfilled its potential, given that it had only nine months of full implementation before Donald Trump was elected U.S. president in 2016. The agreement started to fall apart after the Trump administration unilaterally quit in 2018 and reimposed all the sanctions lifted by the JCPOA. The administration then added more sanctions even though Trump officials acknowledged Iran was complying with the deal at that time. Iran eventually ramped up its nuclear activities, busting through the limitations established by the JCPOA on stockpiles, enrichment levels, and use of advanced centrifuges, as well as provisions for strict international monitoring.

As of February 2022, Iran possessed more than 3,000 kilograms of enriched uranium. That is more than 10 times the stockpile allowed under the JCPOA and includes more than 30 kilograms enriched to 60 percent uranium-235, perilously close to weapons grade.4 By May 10, the stockpile was at more than 40 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent, Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) told the European Parliament.5 Although much of this activity can be reversed, the knowledge Iranian scientists and engineers have acquired is permanent, meaning that the long-term nonproliferation benefits of the agreement, if restored, would inevitably be less than when the deal was implemented in 2016.6

U.S. officials continue to assert that the JCPOA, whose limitations on enriched uranium stockpiles are supposed to last until 2031, remains beneficial. “We are still at a point where, if we were able to negotiate a mutual return to compliance, that breakout time would be prolonged from where it is now,” State Department spokesman Ned Price said on May 4, 2022.7 “We would have greater transparency. There would be those permanent, verifiable limits reimposed on Iran. That would be in our national security interest.”

Yet, the domestic political climates in Iran and the United States have shifted in ways that have made compromise more difficult. It remains to be seen if there is sufficient political will and creativity to end the impasse.

Weakened Iranian Pragmatists

Trump’s abrogation of the JCPOA gravely undermined the so-called pragmatist camp in Iran that had negotiated and championed the deal, making President Hassan Rouhani and his team look foolish and naïve. This perception complicated negotiations even after the Biden administration took office, with Iran refusing to sit directly with the U.S. delegation in Vienna and initially seeking some form of guarantee that a subsequent U.S. administration would not quit the deal again. Nevertheless, substantial progress was made in indirect talks, which resumed in April 2021.

Negotiations paused in June 2021 for the Iranian presidential elections. Rouhani’s successor, Ebrahim Raisi, was handpicked by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in large part for his hard-line views on domestic and foreign policy, as well as his fealty to Khamenei. Raisi, like Khamenei, was critical of the JCPOA and named a cabinet of like-minded officials.8 The new Iranian administration then waited until November 2021 to send a team to Vienna, where talks resumed with the other parties to the JCPOA (China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) plus the European Union.

As with the previous team, the Iranians refused to meet directly with U.S. negotiators, arguing that the United States had forfeited its right to be considered a JCPOA party by quitting the agreement without cause. The Iranians also initially demanded the unfreezing of billions of dollars of their assets stuck in foreign banks9 as a precondition for negotiations, a nonstarter for Washington while the Iranian nuclear program continued to advance.

There was also a wrangle over a separate but related issue: a long-running dispute between Iran and the IAEA over Iran’s alleged efforts nearly two decades ago related to possible nuclear weapons development. An 11th-hour trip to Tehran by Grossi in early March 2022 resulted in an agreement that Iran would provide additional documentation about suspect sites in time for the IAEA Board of Governors meeting in June.10 Grossi complained on May 10 in a session with the European Parliament that Iranian officials have been slow to provide clarification about the origin of traces of enriched uranium found at the sites.11

A more positive development had occurred on February 4, when the Biden administration announced that it was waiving sanctions on foreign cooperation with Iran’s civil nuclear program. Price said that the waivers were in the U.S. “vital national interest regardless of what happens with the JCPOA.”12 In fact, the waivers were necessary prerequisites to a deal because they facilitate the disposition of Iran’s excess stockpile of enriched uranium and the resumption of modifications to the Arak heavy-water reactor to make it more proliferation resistant. The waiver would also allow an underground site at Fordow to cease uranium enrichment and return to the production of isotopes for medical use as specified by the original agreement, Price explained.

The Ukraine Effect

According to participants, negotiators completed a 27-page draft agreement in mid-March that specified the steps Iran would take to roll back its nuclear progress in return for relief from U.S. nuclear-related sanctions.13 Talks had been interrupted in late February by a Russian effort to exploit the JCPOA to circumvent some of the sanctions imposed on Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. In the end, the Russians backed down and accepted the terms of the original deal, under which Russia agreed to accept excess enriched U-235 from Iran and provide other civil nuclear cooperation that does not deal with broader Iranian-Russian trade issues. Nevertheless, the momentum in Vienna was broken by the war in Ukraine and the Russian attempt to hold the Vienna talks hostage to sanctions exemptions. Despite valiant efforts by EU envoy Enrique Mora14 and other would-be mediators, the stalemate has continued.

In interviews with ACT and in Iranian press reports, Iranian analysts have stated that, for domestic political reasons, Raisi feels he needs to squeeze more concessions from the United States than the Rouhani team obtained, resulting in the demand to take the IRGC off the list of foreign terrorist organizations. At the same time, Iran is no longer feeling the pinch of U.S. secondary sanctions to the extent it was a few years ago. Iran has managed to increase its oil exports, primarily to China, to more than one million barrels a day. Given the steep rise in prices due to the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, Iran is earning sufficient revenues to meet its basic needs.15 Even if the United States could enforce secondary sanctions on Iranian oil customers, there is little motivation to do so at a time of global shortages and sky-high energy prices.

Biden’s Ambivalence

As the Iran issue appears to have lost urgency, the Biden administration also seems increasingly ambivalent about the value of the JCPOA when weighed against the potential domestic political costs of compromising with a long-time U.S. adversary. President Joe Biden did not announce a U.S. return to the JCPOA on the first day of his presidency as many proponents of the deal had hoped. He did appoint an experienced Iran envoy, Rob Malley, who had participated in the original negotiations, within a week of taking office. Yet, Malley took months consulting with U.S. allies and Middle Eastern partners such as Israel, which opposed the original deal, and with Arab countries, which were concerned about the increased oil revenues that Iran would receive and possibly divert to its regional partners.

Biden administration officials such as Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan also talked about their desire for a “longer and stronger” deal before the old one could be revived.16 This language reflected a genuine desire to improve on the original and an effort to placate powerful deal opponents among Democrats such as Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Robert Menendez (N.J.), who had the power to slow the confirmation of Biden appointees in a closely divided Senate.17 As a result, precious time was lost before the Iranian presidential elections and the replacement of the Iranian negotiation team with JCPOA skeptics.

With U.S. midterm elections now approaching, the Biden administration seems particularly leery of acceding to Iran’s demands regarding the IRGC. Although it is largely a conscript organization, IRGC elements, particularly the Qods Force, have been implicated in attacks on U.S. military forces in the Middle East, as well as in support of anti-U.S. nonstate actors, such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthis, and Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Units. Biden appears concerned about looking weak and the impact this might have on select races in November when Democrats are at risk of losing control of the House and Senate.

For Biden, the JCPOA was never the signature issue it was for President Barack Obama, who considered the deal his most important foreign policy achievement. Biden has been much more engaged in solidifying NATO in the face of Russian aggression and is also eager to focus on the challenge of China. He appears unwilling to expend as much political capital as Obama did on the Iran agreement even though public opinion polls show that the deal is more popular in the United States now than it was in 2015 and experts acknowledge that there is no realistic plan B for containing Iran’s nuclear ambitions in the long term.18

Iran’s Goal

One possible reason for the lack of urgency in Washington over Iran’s nuclear advances is that the U.S. intelligence community continues to find no evidence that Iran has resumed work on developing an actual nuclear weapon, despite its growing stockpile of enriched uranium.19 Iran has always denied that it seeks to build nuclear weapons, but the fact that it was found to have possessed a clandestine program two decades ago20 and that its cooperation with the IAEA has been less than stellar has fueled suspicion and concern. Still, Iran’s program has been the slowest moving in the history of nuclear proliferation, given that its activities began in the 1950s under the U.S.-led Atoms for Peace initiative.

Since Iran’s nuclear work first began, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have built nuclear arsenals, but Iran has not. The Iranian program was suspended following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when Western companies halted work on nuclear projects in Iran. The program was revived in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war when Iran feared that Iraq was developing nuclear weapons. Progress in the 1990s was slow, inhibited by successful U.S. appeals to Russia and China, but picked up in the mid-2000s after the 2005 election of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The organized weapons program halted in 2003 and certain weaponization-related activities continued until 2009, but there has been no evidence of illicit weapons work since then, according to the IAEA and the U.S. National Intelligence Council. The JCPOA halted and rolled back the program significantly until the Trump withdrawal.

As a signatory of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, Iran has pledged to remain free of nuclear weapons, a pledge it reiterated in the preamble of the JCPOA. The key provisions of the agreement were designed to make it extremely difficult for Iran to violate that pledge without being detected. If Iran returns to compliance again, it must blend down or export hundreds of tons of excess U-235 and remove advanced centrifuges. These actions must be verified and monitored by the IAEA, with no time limits on that cooperation, to provide confidence that Iran cannot “sneak out” and amass material clandestinely for a bomb. Iran, under its interpretation of the JCPOA, says it is entitled to breach these limits again if the United States does not fulfill its obligations to waive key sanctions on Iran’s oil exports and financial transactions.21

Supporters of the agreement concede that, because of the additional technical knowledge that Iran has accumulated since the United States unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018, Iran’s ability to break out and amass sufficient material for a single nuclear weapon has been significantly increased.22 When combined with the limitations on uranium stockpiles and IAEA monitoring, however, a restored agreement should still provide sufficient time for the international community to react should violations occur. Without an agreement, Iran could continue amassing larger and larger quantities of U-235 enriched to higher and higher levels. This activity would be inherently destabilizing. It could spark a nuclear arms race in the region, prompting Saudi Arabia in particular to acquire a nuclear arsenal, and provoke new sabotage or other kinds of attacks on Iran by Israel or even the United States, both of which have vowed to never allow Iran to develop nuclear weapons.

The Role of Congress

Because the agreement would be a restoration of the original, not a rewrite, the Biden administration has argued that it is not obliged to submit the deal for formal review by Congress under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Act of 2015.23 Malley testified on May 25 before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, however, that the administration will invoke the law if a deal is struck to allow Congress to publicly debate the issue.24 It is extremely doubtful that a veto-proof majority of two-thirds of the House and Senate could be assembled to block restoration of the JCPOA. Even so, Republicans are united against the deal; even some Democrats, most prominently those who did not support the agreement in 2015, have expressed concern that it does not cover non-nuclear issues such as Iran’s growing arsenal of ballistic missiles and drones.25

A more serious issue is what might happen in 2024 if a Republican is elected president. Trump and other GOP hopefuls are opposed to the JCPOA and might follow the precedent set by Trump in 2018. It will be important for supporters of the agreement to underline the negative consequences of the Trump withdrawal for U.S. nonproliferation and regional security interests. It will also be key for the United States and other parties to intensify efforts to deescalate broader tensions between Iran and its neighbors and between Iran and Israel to build a stronger foundation for the JCPOA.

A more serious issue is what might happen in 2024 if a Republican is elected president. Trump and other GOP hopefuls are opposed to the JCPOA and might follow the precedent set by Trump in 2018. It will be important for supporters of the agreement to underline the negative consequences of the Trump withdrawal for U.S. nonproliferation and regional security interests. It will also be key for the United States and other parties to intensify efforts to deescalate broader tensions between Iran and its neighbors and between Iran and Israel to build a stronger foundation for the JCPOA.

Fortunately, Iran, a Shia theocracy, has already made some progress toward improved relations with its Sunni Arab rivals Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Iran and Israel remain bitter adversaries, but the removal of Benjamin Netanyahu as Israeli prime minister and the formation of a broad coalition government in Israel has led to less prickly relations between Israel and the Biden administration. There was also a brief pause in Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear scientists and facilities. That appears to have ended, however, with the May 22 assassination of an IRGC officer in Tehran and a mysterious "explosion" May 26 near the Parchin military facility that killed an Iranian engineer.26

Much will depend on Iran’s evaluation of the material benefits it is slated to receive if it returns to compliance with the JCPOA. Iranians have suffered greatly from Trump’s maximum-pressure campaign, not to mention the COVID-19 epidemic, endemic economic mismanagement, and corruption. According to Iranian statistics, the percentage of Iranians classified as poor has doubled over the past three years to more than a third of the population.27 Inflation is higher than 40 percent, and unemployment is also in double digits. The waiving of U.S. secondary sanctions on key sectors of the Iranian economy, especially oil and gas, and the repatriation of some $100 billion in hard currency assets would provide a substantial, if temporary, boost to Iran’s economy. To sustain these benefits, Iran would need to institute reforms of its own, increasing transparency in its banking sector, reducing consumer subsidies, and tackling corruption more effectively.

Iran’s Foreign Policy Orientation

Another unfortunate result of the maximum-pressure campaign and a factor in Iran’s ambivalence about returning to compliance with the JCPOA has been the solidification of the Iranian regime’s anti-Western orientation. The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA vindicated Khamenei’s view that the United States is untrustworthy and led him to boost Iran’s economic dependence on China and strategic cooperation with Russia, countries that do not criticize the Islamic Republic for human rights abuses or foreign adventurism. This orientation does not reflect the views of many Iranian people, who traditionally have looked toward Western countries for trade and investment, as well as for cultural ties, underscoring the fact that a large Iranian diaspora resides primarily in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. Regardless, the “look to the East” policy is still supported by hard-liners who now control all elements of the Iranian government and is important to their domestic political power base.28

When the original nuclear deal was reached, supporters made clear that it was valuable on its own merits. Still, there was hope that the JCPOA, as the product of unprecedented, direct, high-level U.S.-Iranian diplomacy, would lead to some broader détente and even normalization of ties between Washington and Tehran. As then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif famously put it, the JCPOA could be “the foundation, not the ceiling” of Iran’s foreign relations, including with the United States.29

When the original nuclear deal was reached, supporters made clear that it was valuable on its own merits. Still, there was hope that the JCPOA, as the product of unprecedented, direct, high-level U.S.-Iranian diplomacy, would lead to some broader détente and even normalization of ties between Washington and Tehran. As then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif famously put it, the JCPOA could be “the foundation, not the ceiling” of Iran’s foreign relations, including with the United States.29

Those hopes have been dashed by the Trump withdrawal and the political backlash against pragmatists in Iran. That said, a revived JCPOA is a prerequisite for any improvement in bilateral ties, including the release of jailed dual nationals and a resumption of people-to-people engagement. It would give the United States a seat at the table again in the joint commission that monitors the JCPOA and thus a venue to raise issues that go beyond the nuclear file. It would facilitate Western support for programs to address climate change and other severe threats to the Iranian people and to the world at large. It would also make it easier for Iran to engage with its neighbors on deescalating tensions and resuming normal diplomatic and economic interaction.30

Despite anti-government protests in Iran regarding the poor economy and harsh repression of civil society, the Iranian system has withstood immense challenges and does not appear likely to fall in the near future. It is incumbent on U.S. policymakers to continue to express their views on Iranian policies that are harmful to the Iranian people and to the interests of the United States and its allies and partners. Yet, one lesson of the past four, if not 40, years has been that the United States should use opportunities to lessen tensions when it is in the interest of both countries and the broader Middle East. As former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage once said, “Diplomacy is the art of letting the other guy have our way.”31

If the JCPOA can be revived, it will show that diplomacy can achieve what military conflict cannot. If it finally collapses, it will sadly confirm that the agreement was merely the exception that proved the rule in four decades of U.S.-Iranian enmity.

ENDNOTES

1. “White House Says Iran Is ‘a Few Weeks or Less’ From Bomb Breakout,” Times of Israel, April 27, 2022.

2. “Secretary of State Blinken Testifies in Senate Foreign Relations Hearing 4/26/22,” April 27, 2022, https://www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/secretary-of-state-blinken-testifies-in-senate-foreign-relations-hearing-4-26-22-transcript.

3. Laura Rozen, “U.S. on Iran Deal Deadlock: ‘We Know the Status Quo Can’t Endure for Long,’” Diplomatic, May 4, 2022, https://diplomatic.substack.com/p/us-on-iran-deal-deadlock-we-know?s=w.

4. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors, “Verification and Monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in Light of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015),” GOV/2022/4, March 3, 2022, pp. 9–10.

5. Rafael Mariano Grossi, “Exchange of Views With European Parliament: The Work of the IAEA at an Unprecedented Moment in History,” May 10, 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/248145/EP_IAEA_20220510dg.pdf.

6. “U.S. Sees Iran’s Nuclear Program as Too Advanced to Restore Key Goal of 2015 Pact,” The Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2022.

7. U.S. Department of State, “Department Press Briefing—May 4, 2022,” May 4, 2022, https://www.state.gov/briefings/department-press-briefing-may-4-2022/.

8. Mehrzad Boroujerdi, “Who’s on Iran’s Current Nuclear Negotiating Team? Some Have Controversial Pasts,” IranSource, January 11, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/whos-on-irans-current-nuclear-negotiating-team-some-have-controversial-pasts/.

9. Barbara Slavin, “Iran Offers Less for More as Vienna Talks Stall,” IranSource, December 6, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/iran-offers-less-for-more-as-vienna-talks-stall/.

10. IAEA, “Joint Statement by HE Mr. Mohammad Eslami, Vice-President and President of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, and HE Mr. Rafael Grossi, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency,” March 5, 2022, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/joint-statement-by-he-mr-mohammad-eslami-vice-president-and-president-of-the-atomic-energy-organization-of-iran-and-he-mr-rafael-grossi-director-general-of-the-international-atomic-energy-agency.

11. “IAEA Warns That Iran Not Forthcoming on Past Nuclear Activities,” Reuters, May 10, 2022.

12. U.S. Department of State, “Department Press Briefing - February 7, 2022,” https://www.state.gov/briefings/department-press-briefing-february-7-2022/.

13. Stephanie Liechtenstein and Nahal Toosi, “Iran Nuclear Talks Freeze Amid Terrorist Label Spat—Even With Deal on the Table,” Politico, April 28, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/iran-nuclear-talks-freeze-amid-terrorist-label-spat-even-with-deal-on-the-table/.

14. Laurence Norman, “Europe to Make Fresh Push to Revive Iran Nuclear Deal,” The Wall Street Journal, May 1, 2022.

15. Parisa Hafezi, “Analysis: Rising Oil Prices Buy Iran Time in Nuclear Talks, Officials Say,” Reuters, May 5, 2022.

16. Steven Erlanger and David E. Sanger, “U.S. and Iran Want to Restore the Nuclear Deal. They Disagree Deeply on What That Means,” The New York Times, May 9, 2021.

17. A U.S. negotiator stated in February 2021 that Menendez was a key factor inhibiting U.S. willingness to quickly return to compliance with the JCPOA. U.S. official, conversation with author, Washington, D.C., February 13, 2022.

18. Matthew Kendrick, “Many U.S. Voters Support a Binding Nuclear Deal With Iran. That Might Not Count for Much,” Morning Consult, February 16, 2022, https://morningconsult.com/2022/02/16/iran-deal-polling-us-voters/; Atlantic Council, “Is There a Plan B for Iran?” YouTube, December 9, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4jLhkO2dHU.

19. U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” February 2022, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2022-Unclassified-Report.pdf.

20. U.S. National Intelligence Council, “National Intelligence Estimate; Iran: Nuclear Intentions and Capabilities,” November 2007, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Reports%20and%20Pubs/20071203_release.pdf.

21. Francois Murphy, Parisa Hafezi, and John Irish, “Exclusive: Iran Nuclear Deal Draft Puts Prisoners, Enrichment, Cash First, Oil Comes Later - Diplomats,” Reuters, February 17, 2022.

22. Laurence Norman, “U.S. Sees Iran’s Nuclear Program as Too Advanced to Restore Key Goal of 2015 Pact,” The Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2022.

23. Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, 42 U.S.C. § 2160e (2015).

24. U.S. Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley, "The JCPOA Negotiations and United States’ Policy on Iran Moving Forward," Testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, May 25, 2022, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/the-jcpoa-negotiations-and-united-states-policy-on-iran-moving-forward05252201

25. Andrew Desiderio, “Congress Fires Its First Warning Shot on Biden’s Iran Deal,” Politico, May 5, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/05/05/congress-warning-biden-iran-deal-00030448.

26. Farnaz Fassihi and Ronen Bergman, "Israel Tells U.S. It Killed Iranian Officer, Official Says," The New York Times, May 25, 2022.

27. Nadereh Chamlou, “Can President Ebrahim Raisi Turn Iran’s Economic Titanic Around?” IranSource, February 1, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/can-president-ebrahim-raisi-turn-irans-economic-titanic-around/.

28. Javad Heiran-Nia, “How Iran’s Interpretation of the World Order Affects Its Foreign Policy,” IranSource, May 11, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/how-irans-interpretation-of-the-world-order-affects-its-foreign-policy/.

29. “Iran Deal Not a ‘Ceiling’: Zarif,” Islamic Republic News Agency, July 14, 2015, https://en.irna.ir/news/81683560/Iran-deal-not-a-ceiling-Zarif.

30. Barbara Slavin, “The Potential Side Benefits of a Revived JCPOA for Middle East Stability,” IranSource, April 5, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/the-potential-side-benefits-of-a-revived-jcpoa-for-middle-east-stability/.

31. Barbara Slavin, Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S. and the Twisted Path to Confrontation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007), p. 223.

Barbara Slavin directs the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council.

Putin’s decision to discard diplomacy and invade Ukraine puts the 77-year taboo against nuclear weapons use to the test. It also has derailed the strategic stability and arms control dialogue between Washington and Moscow, made a mockery of the repeated security assurances that nuclear-armed states will not attack non-nuclear states, and created a major challenge for the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) regime.

Putin’s decision to discard diplomacy and invade Ukraine puts the 77-year taboo against nuclear weapons use to the test. It also has derailed the strategic stability and arms control dialogue between Washington and Moscow, made a mockery of the repeated security assurances that nuclear-armed states will not attack non-nuclear states, and created a major challenge for the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) regime.

In the U.S. view, the ostensible reason for the impasse is an Iranian demand for sanctions relief that goes beyond what is required by the JCPOA. Iran has been seeking removal of the foreign terrorist designation of a powerful branch of the Iranian military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The U.S. Department of State added this designation in 2019 as the Trump administration ran low on new targets to sanction under its “maximum pressure” campaign. The Biden administration, which says it wants to revive the JCPOA, has indicated that it would be willing to lift the designation, which has little practical effect because the IRGC remains subject to numerous other U.S. sanctions, if Iran makes a gesture of its own.

In the U.S. view, the ostensible reason for the impasse is an Iranian demand for sanctions relief that goes beyond what is required by the JCPOA. Iran has been seeking removal of the foreign terrorist designation of a powerful branch of the Iranian military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The U.S. Department of State added this designation in 2019 as the Trump administration ran low on new targets to sanction under its “maximum pressure” campaign. The Biden administration, which says it wants to revive the JCPOA, has indicated that it would be willing to lift the designation, which has little practical effect because the IRGC remains subject to numerous other U.S. sanctions, if Iran makes a gesture of its own. A more serious issue is what might happen in 2024 if a Republican is elected president. Trump and other GOP hopefuls are opposed to the JCPOA and might follow the precedent set by Trump in 2018. It will be important for supporters of the agreement to underline the negative consequences of the Trump withdrawal for U.S. nonproliferation and regional security interests. It will also be key for the United States and other parties to intensify efforts to deescalate broader tensions between Iran and its neighbors and between Iran and Israel to build a stronger foundation for the JCPOA.

A more serious issue is what might happen in 2024 if a Republican is elected president. Trump and other GOP hopefuls are opposed to the JCPOA and might follow the precedent set by Trump in 2018. It will be important for supporters of the agreement to underline the negative consequences of the Trump withdrawal for U.S. nonproliferation and regional security interests. It will also be key for the United States and other parties to intensify efforts to deescalate broader tensions between Iran and its neighbors and between Iran and Israel to build a stronger foundation for the JCPOA. When the original nuclear deal was reached, supporters made clear that it was valuable on its own merits. Still, there was hope that the JCPOA, as the product of unprecedented, direct, high-level U.S.-Iranian diplomacy, would lead to some broader détente and even normalization of ties between Washington and Tehran. As then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif famously put it, the JCPOA could be “the foundation, not the ceiling” of Iran’s foreign relations, including with the United States.

When the original nuclear deal was reached, supporters made clear that it was valuable on its own merits. Still, there was hope that the JCPOA, as the product of unprecedented, direct, high-level U.S.-Iranian diplomacy, would lead to some broader détente and even normalization of ties between Washington and Tehran. As then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif famously put it, the JCPOA could be “the foundation, not the ceiling” of Iran’s foreign relations, including with the United States. More than two months have elapsed since the start of the conflict. Although the actual fighting is taking place between nuclear-armed Russia and non-nuclear Ukraine, the threatening shadow of the nuclear weapons possessed by the United States and NATO is palpable. Since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, this is the first real engagement between the United States and Russia where they are indirectly yet directly involved. Millions of lives have been disrupted, and several thousand people have died. This is an irreparable and inconsolable human loss.

More than two months have elapsed since the start of the conflict. Although the actual fighting is taking place between nuclear-armed Russia and non-nuclear Ukraine, the threatening shadow of the nuclear weapons possessed by the United States and NATO is palpable. Since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, this is the first real engagement between the United States and Russia where they are indirectly yet directly involved. Millions of lives have been disrupted, and several thousand people have died. This is an irreparable and inconsolable human loss. Nations cannot defend themselves by using nuclear weapons. They can only do so by deterring the adversary’s use of a nuclear weapon by the threat of retaliation. In fact, the threat of using these weapons in any scenario other than retaliation, such as against terrorists, conventional offensives, and cyberattacks or space attacks, could only be counterproductive by escalating hostilities. Clearly, these weapons are most effective for only a narrow role.

Nations cannot defend themselves by using nuclear weapons. They can only do so by deterring the adversary’s use of a nuclear weapon by the threat of retaliation. In fact, the threat of using these weapons in any scenario other than retaliation, such as against terrorists, conventional offensives, and cyberattacks or space attacks, could only be counterproductive by escalating hostilities. Clearly, these weapons are most effective for only a narrow role. In August, hundreds of diplomats representing the states-parties, along with representatives of civil society, will convene at UN headquarters in New York for the 10th NPT Review Conference. This event occurs more than a quarter-century after the states-parties agreed on the indefinite extension of the NPT at the 1995 review and extension conference.

In August, hundreds of diplomats representing the states-parties, along with representatives of civil society, will convene at UN headquarters in New York for the 10th NPT Review Conference. This event occurs more than a quarter-century after the states-parties agreed on the indefinite extension of the NPT at the 1995 review and extension conference. I would say that the argument of some that Russia's violation of the Budapest Memorandum shows that security assurances are worthless is just wrong. It's Russia that violated the security assurances. That's an indictment of Russia, not of the utility of security assurances that the other nuclear-weapon states have given, including the United States, and implement faithfully.

I would say that the argument of some that Russia's violation of the Budapest Memorandum shows that security assurances are worthless is just wrong. It's Russia that violated the security assurances. That's an indictment of Russia, not of the utility of security assurances that the other nuclear-weapon states have given, including the United States, and implement faithfully. Scheinman: There’s no doubt that China’s rapid nuclear buildup is out of step with the other nuclear-weapon states. It is certainly out of step with the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. I'd say it's not exactly keeping with the spirit of Article VI, and that merits some attention at the review conference. Our approach has been to seek bilateral discussions with China on measures to reduce and manage strategic risks. President Biden conveyed our interest to President Xi Jinping last November, suggesting that we ought to have some commonsense guardrails in place to ensure that competition doesn't veer into conflict. To this point, China has not engaged or shown interest in engaging. We hope China will take a fresh look at this and see the value of exchanges both for regional stability and for nuclear security.

Scheinman: There’s no doubt that China’s rapid nuclear buildup is out of step with the other nuclear-weapon states. It is certainly out of step with the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. I'd say it's not exactly keeping with the spirit of Article VI, and that merits some attention at the review conference. Our approach has been to seek bilateral discussions with China on measures to reduce and manage strategic risks. President Biden conveyed our interest to President Xi Jinping last November, suggesting that we ought to have some commonsense guardrails in place to ensure that competition doesn't veer into conflict. To this point, China has not engaged or shown interest in engaging. We hope China will take a fresh look at this and see the value of exchanges both for regional stability and for nuclear security. The Russian exercise included “electronic launches” of dual-capable, road-mobile Iskander-M ballistic missiles against targets such as airfields, equipment depots, and military command posts. The Russian Defense Ministry said that more than 100 troops participated in the simulation launched from Kaliningrad, which is located between the NATO countries of Lithuania and Poland along the Baltic coast. Russia has used conventional Iskander-M missiles extensively in Ukraine.

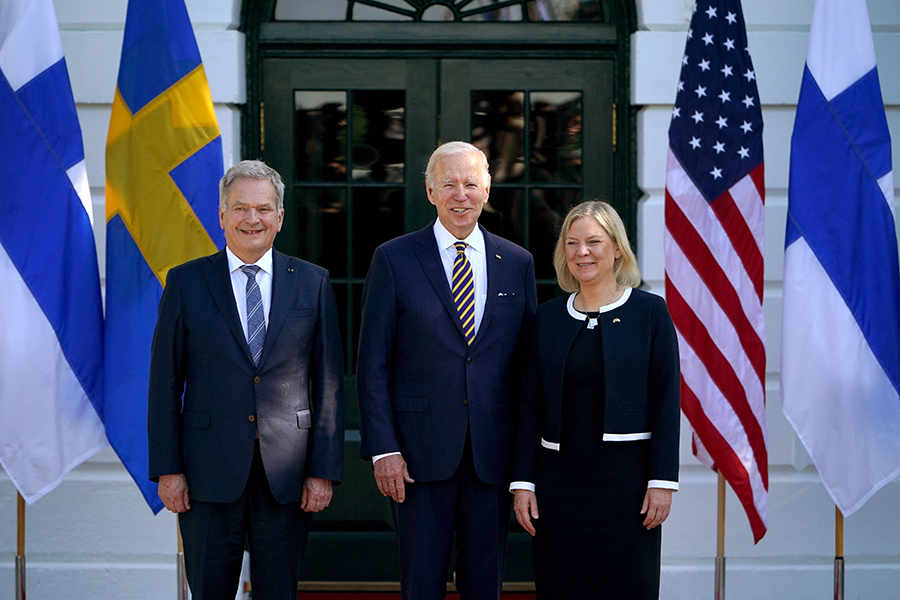

The Russian exercise included “electronic launches” of dual-capable, road-mobile Iskander-M ballistic missiles against targets such as airfields, equipment depots, and military command posts. The Russian Defense Ministry said that more than 100 troops participated in the simulation launched from Kaliningrad, which is located between the NATO countries of Lithuania and Poland along the Baltic coast. Russia has used conventional Iskander-M missiles extensively in Ukraine. Sweden declared its intentions to seek NATO membership on May 15, shortly after Finland confirmed its move. Three days later, the countries filed formal applications at NATO headquarters in Brussels.

Sweden declared its intentions to seek NATO membership on May 15, shortly after Finland confirmed its move. Three days later, the countries filed formal applications at NATO headquarters in Brussels. Finland and Sweden were nonaligned during the Cold War and maintained formal military neutrality even as their armed forces contributed to Western operations. Both countries are considered to be NATO’s closest geopolitical partners, possessing vibrant democracies, strong economies, and competent militaries. Since Russia invaded Ukraine and upended European stability, Finland and Sweden have become increasingly unsettled by the Russian threat and experienced a stunning surge in support among their politicians and publics to seek security in the alliance.

Finland and Sweden were nonaligned during the Cold War and maintained formal military neutrality even as their armed forces contributed to Western operations. Both countries are considered to be NATO’s closest geopolitical partners, possessing vibrant democracies, strong economies, and competent militaries. Since Russia invaded Ukraine and upended European stability, Finland and Sweden have become increasingly unsettled by the Russian threat and experienced a stunning surge in support among their politicians and publics to seek security in the alliance. Since invading Ukraine, Russia briefly occupied and disrupted activities at Chernobyl, the site of the 1986 reactor meltdown, and still controls the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant, which includes six reactors.

Since invading Ukraine, Russia briefly occupied and disrupted activities at Chernobyl, the site of the 1986 reactor meltdown, and still controls the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant, which includes six reactors. The United States and its allies have spent billions of dollars arming Ukraine since the Russian invasion on Feb. 24. As Russia struggles to maintain control of the fight in the Donbas in eastern Ukraine, it has continued to fire all kinds of missiles targeting key weapons facilities and industrial bases. On May 2, the U.S. Defense Department reported observing more than 2,125 Russian missile launches since the beginning of the invasion. While the barrage continues, the allies are not only learning valuable lessons about how these conventional missile systems are used and performing, but also taking steps to upgrade their own military equipment as they donate older models to Ukraine.

The United States and its allies have spent billions of dollars arming Ukraine since the Russian invasion on Feb. 24. As Russia struggles to maintain control of the fight in the Donbas in eastern Ukraine, it has continued to fire all kinds of missiles targeting key weapons facilities and industrial bases. On May 2, the U.S. Defense Department reported observing more than 2,125 Russian missile launches since the beginning of the invasion. While the barrage continues, the allies are not only learning valuable lessons about how these conventional missile systems are used and performing, but also taking steps to upgrade their own military equipment as they donate older models to Ukraine. Overall, more than 40,000 troops are now under direct NATO command on the alliance’s eastern front. In addition, The Washington Post reported in early April that the Pentagon had increased the number of U.S. military personnel in Europe from 60,000 to more than 100,000 since February 2022. The Post, quoting an anonymous senior defense official, also reported that there will be a permanent force posture change in Europe, including troops from other NATO member states and possibly including a greater U.S. presence. Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated on April 5, “I believe a lot of our allies, especially those such as the Baltics or Poland or Romania…are very willing to establish permanent bases. They will build them and pay for them.”

Overall, more than 40,000 troops are now under direct NATO command on the alliance’s eastern front. In addition, The Washington Post reported in early April that the Pentagon had increased the number of U.S. military personnel in Europe from 60,000 to more than 100,000 since February 2022. The Post, quoting an anonymous senior defense official, also reported that there will be a permanent force posture change in Europe, including troops from other NATO member states and possibly including a greater U.S. presence. Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated on April 5, “I believe a lot of our allies, especially those such as the Baltics or Poland or Romania…are very willing to establish permanent bases. They will build them and pay for them.” In terms of aiding Ukraine’s defense against Russian aggression, the most symbolic move so far was Congress’ decision to pass legislation modeled after the World War II-era Lend-Lease Act, which enabled the Roosevelt administration to quickly provide arms to U.S. allies and turn the tide of that conflict.

In terms of aiding Ukraine’s defense against Russian aggression, the most symbolic move so far was Congress’ decision to pass legislation modeled after the World War II-era Lend-Lease Act, which enabled the Roosevelt administration to quickly provide arms to U.S. allies and turn the tide of that conflict. Enrique Mora, the lead negotiator for the European Union, met with Iran’s lead negotiator, Ali Bagheri Kani, on May 11–12 over Iran’s demand that the United States remove the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) from the U.S. list of foreign terrorist organizations. The terrorism designation is the last major obstacle to concluding an agreement to restore the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. (See

Enrique Mora, the lead negotiator for the European Union, met with Iran’s lead negotiator, Ali Bagheri Kani, on May 11–12 over Iran’s demand that the United States remove the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) from the U.S. list of foreign terrorist organizations. The terrorism designation is the last major obstacle to concluding an agreement to restore the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. (See