March 2019

By Michael T. Klare

It may have been the strangest christening in the history of modern shipbuilding. In April 2016, the U.S. Navy and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) celebrated the initial launch of Sea Hunter, a sleek, 132-foot-long trimaran that one observer aptly described as “a Klingon bird of prey.” More unusual than its appearance, however, is the size of the its permanent crew: zero.

Originally designated by DARPA as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle (ACTUV), Sea Hunter is designed to travel the oceans for months at a time with no onboard crew, searching for enemy submarines and reporting their location and findings to remote human operators. If this concept proves viable (Sea Hunter recently completed a round trip from San Diego, Calif., to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with no crew) swarms of ACTUVs may be deployed worldwide, some capable of attacking submarines on their own, in accordance with sophisticated algorithms.

Originally designated by DARPA as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle (ACTUV), Sea Hunter is designed to travel the oceans for months at a time with no onboard crew, searching for enemy submarines and reporting their location and findings to remote human operators. If this concept proves viable (Sea Hunter recently completed a round trip from San Diego, Calif., to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with no crew) swarms of ACTUVs may be deployed worldwide, some capable of attacking submarines on their own, in accordance with sophisticated algorithms.

The launching of Sea Hunter and the development of software and hardware allowing it to operate autonomously on the high seas for long stretches of time are the product of a sustained drive by senior Navy and Pentagon officials to reimagine the future of naval operations. Rather than deploy combat fleets composed of large, well-equipped, and extremely expensive major warships, the Navy will move toward deploying smaller numbers of crewed vessels accompanied by large numbers of unmanned ships. “ACTUV represents a new vision of naval surface warfare that trades small numbers of very capable, high-value assets for large numbers of commoditized, simpler platforms that are more capable in the aggregate,” said Fred Kennedy, director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office. “The U.S. military has talked about the strategic importance of replacing ‘king’ and ‘queen’ pieces on the maritime chessboard with lots of ‘pawns,’ and ACTUV is a first step toward doing exactly that.”

The Navy is not alone in exploring future battle formations involving various combinations of crewed systems and swarms of autonomous and semiautonomous robotic weapons. The Air Force is testing software to enable fighter pilots to guide accompanying unmanned aircraft toward enemy positions, whereupon the drones will seek and destroy air defense radars and other key targets on their own. The Army is testing an unarmed robotic ground vehicle, the Squad Multipurpose Equipment Transport (SMET) and has undertaken development of a Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV). These systems, once fielded, would accompany ground troops and crewed vehicles in combat, trying to reduce U.S. soldiers’ exposure to enemy fire. Similar endeavors are under way in China, Russia, and a score of other countries.1

For advocates of such scenarios, the development and deployment of autonomous weapons systems, or “killer robots,” as they are often called, offer undeniable advantages in combat. Comparatively cheap and able to operate 24 hours a day without tiring, the robotic warriors could help reduce U.S. casualties. When equipped with advanced sensors and artificial intelligence (AI), moreover, autonomous weapons could be trained to operate in coordinated swarms, or “wolfpacks,” overwhelming enemy defenders and affording a speedy U.S. victory. “Imagine anti-submarine warfare wolfpacks,” said former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work at the christening of Sea Hunter. “Imagine mine warfare flotillas, distributed surface-warfare action groups, deception vessels, electronic warfare vessels”—all unmanned and operating autonomously.

Although the rapid deployment of such systems appears highly desirable to Work and other proponents of robotic systems, their development has generated considerable alarm among diplomats, human rights campaigners, arms control advocates, and others who fear that deploying fully autonomous weapons in battle would severely reduce human oversight of combat operations, possibly resulting in violations of the laws of war, and could weaken barriers that restrain escalation from conventional to nuclear war. For example, would the Army’s proposed RCV be able to distinguish between enemy combatants and civilian bystanders in a crowded urban battle space, as required by international law? Might a wolfpack of sub hunters, hot on the trail of an enemy submarine carrying nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, provoke the captain of that vessel to launch its weapons to avoid losing them to a presumptive U.S. pre-emptive strike?

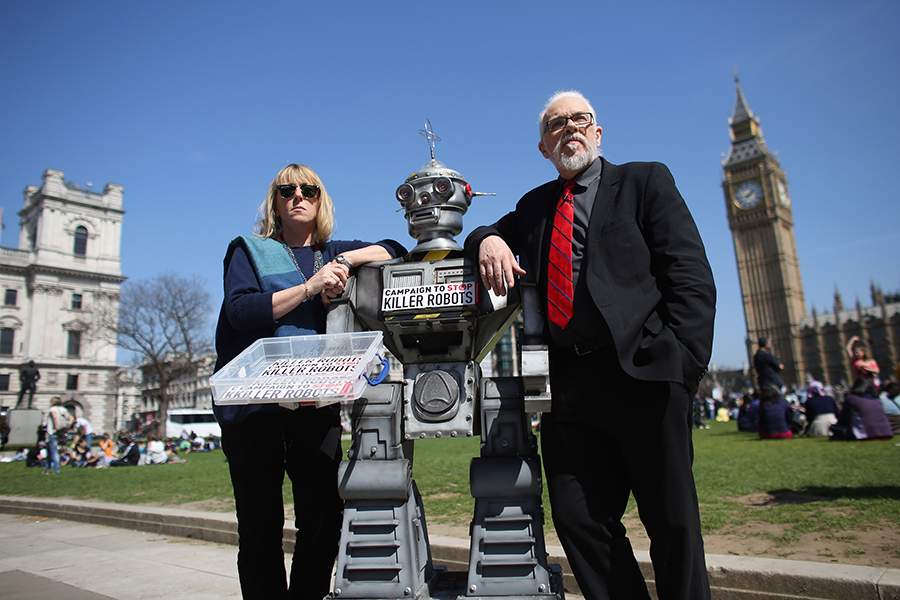

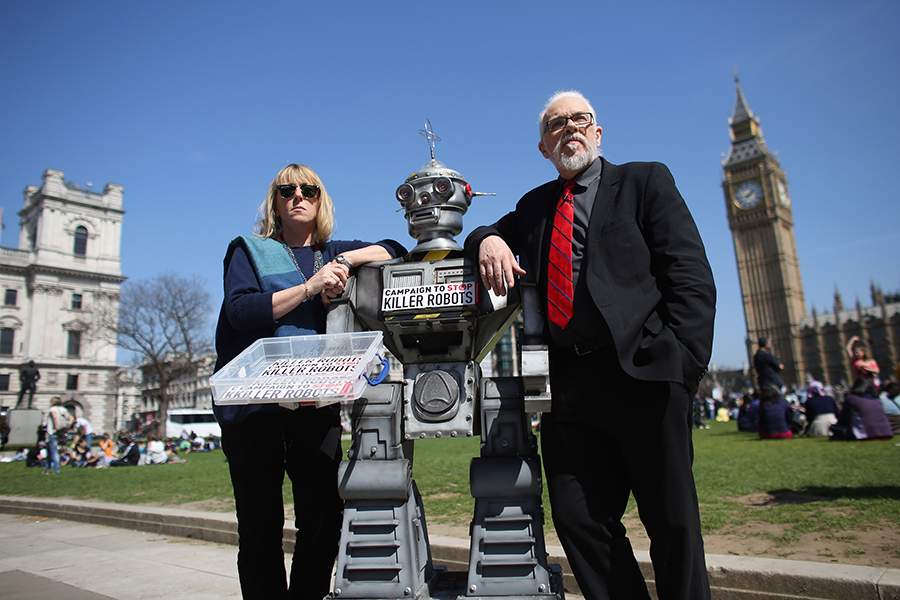

These and other such questions have sparked a far-ranging inquiry into the legality, morality, and wisdom of deploying fully autonomous weapons systems. This debate has gained momentum as the United States, Russia, and several other countries have accelerated their development of such weapons, each claiming they must do so to prevent their adversaries from gaining an advantage in these new modes of warfare. Concerned by these developments, some governments and a coalition of nongovernmental organizations, under the banner of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, have sought to ban their deployment altogether.

Ever-Increasing Degrees of Autonomy

Autonomous weapons systems are lethal devices that have been empowered by their human creators to survey their surroundings, identify potential enemy targets, and independently choose to attack those targets on the basis of sophisticated algorithms. Such systems require the integration of several core elements: a mobile combat platform, such as a drone aircraft, ship, or ground vehicle; sensors of various types to scrutinize the platform’s surroundings; processing systems to classify objects discovered by the sensors; and algorithms directing the platform to initiate attack when an allowable target is detected. The U.S. Department of Defense describes an autonomous weapons system as a “weapons system that, once activated, can select and engage targets without further intervention by a human operator.”2

Few weapons in active service presently exhibit all of these characteristics. Many militaries employ close-in naval defense weapons such as the U.S. Phalanx gun system that can fire autonomously when a ship is under attack by enemy planes or missiles. Yet, such systems cannot independently search for and strike enemy assets on their own, and human operators are always present to assume control if needed.3 Many air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles are able to attack human-selected targets, such as planes or tanks, but cannot hover or loiter to identify potential threats. One of the few systems to possess this capability is Israel’s Harpy airborne anti-radiation drone, which can loiter for several hours over a certain area to search for and destroy enemy radars.4

Few weapons in active service presently exhibit all of these characteristics. Many militaries employ close-in naval defense weapons such as the U.S. Phalanx gun system that can fire autonomously when a ship is under attack by enemy planes or missiles. Yet, such systems cannot independently search for and strike enemy assets on their own, and human operators are always present to assume control if needed.3 Many air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles are able to attack human-selected targets, such as planes or tanks, but cannot hover or loiter to identify potential threats. One of the few systems to possess this capability is Israel’s Harpy airborne anti-radiation drone, which can loiter for several hours over a certain area to search for and destroy enemy radars.4

Autonomy, then, is a matter of degree, with machines receiving ever-increasing capacity to assess their surroundings and decide what to strike and when. As described by the U.S. Congressional Research Service, autonomy is “the level of independence that humans grant a system to execute a given task.” Autonomy “refers to a spectrum of automation in which independent decision-making can be tailored for a specific mission.” Put differently, autonomy refers to the degree to which humans are taken “out of the loop” of decision-making, with AI-empowered machines assuming ever-greater responsibility for critical combat decisions.

This emphasis on the “spectrum of automation” is important because, for the most part, nations have yet to deploy fully autonomous weapon systems on the battlefield. Under prevailing U.S. policy, as enshrined in a November 2012 Defense Department directive, “autonomous and semi-autonomous weapons systems shall be designed to allow commanders and operators to exercise appropriate levels of human judgment over the use of force.” Yet, this country, like others, evidently is developing and testing weapons that would allow for ever-diminishing degrees of human control over their future use.

The U.S. Army has devised a long-term strategy for the development of robotic and autonomous systems (RAS) and their integration into the combat force. To start, the Army envisions an evolutionary process under which it will first deploy unarmed, unmanned utility vehicles and trucks, followed by the introduction of armed robotic vehicles with ever-increasing degrees of autonomy. “The process to improve RAS autonomy,” the Army explained in 2017, “takes a progressive approach that begins with tethered systems, followed by wireless remote control, teleoperation, semi-autonomous functions, and then fully autonomous systems.”5

Toward this end, the Army is proceeding to acquire the SMET, an unmanned vehicle designed to carry infantry combat supplies for up to 60 miles over a 72-hour period. In May 2018, the Army announced that it would begin field-testing four prototype SMET systems, with an eye to procuring one such design in large numbers. It will then undertake development of an RCV for performing dangerous missions at the front edge of the battlefield.6

Similarly, the U.S. Navy is pursuing prototype systems such as Sea Hunter and the software allowing them to operate autonomously for extended periods. DARPA is also testing unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs)—miniature submarines that could operate for long periods of time, searching for enemy vessels and attacking them under certain predefined conditions. The Air Force is developing advanced combat drones capable of operating autonomously if communications with human operators are lost when flying in high-threat areas.

Other nations also are pursuing these technologies. Russia, for example, has unveiled several unmanned ground vehicles, including the Uran-9 small robotic tank and the Vikhr heavy tank; each can carry an assortment of guns and missiles and operate with some degree of autonomy. China reportedly is working on a range of autonomous and semiautonomous unmanned air-, ground-, and sea-based systems. Both countries have announced plans to invest in these systems with ever-increasing autonomy as time goes on.

An Arms Race in Autonomy?

In developing and deploying these weapons systems, the United States and other countries appear to be motivated largely by the aspirations of their own military forces, which see various compelling reasons for acquiring robotic weapons. For the U.S. Navy, it is evident that cost and vulnerability calculations are leading the drive to acquire UUVs and unmanned surface vessels. Naval analysts believe that it might be possible to acquire hundreds of robotic vessels for the price of just one modern destroyer, and large capital ships are bound to be prime targets for enemy forces in any future military clash; while a swarm of robot ships would be more difficult to target and losing even a dozen of them would have a lesser effect on the outcome of combat.7

The Army appears to be thinking along similar lines, seeking to substitute robots for dismounted soldiers and crewed vehicles in highly exposed front-line engagements.

These institutional considerations, however, are not the only drivers for developing autonomous weapons systems. Military planners around the world are fully aware of the robotic ambitions of their competitors and are determined to prevail in what might be called an “autonomy race.” For example, the U.S. Army’s 2017 Robotic and Autonomous Systems Strategy states, “Because enemies will attempt to avoid our strengths, disrupt advanced capabilities, emulate technological advantages, and expand efforts beyond physical battlegrounds…the Army must continuously assess RAS efforts and adapt.” Likewise, senior Russian officials, including President Vladimir Putin, have emphasized the importance of achieving pre-eminence in AI and autonomous weapons systems.

Arms racing behavior is a perennial concern for the great powers, because efforts by competing states to gain a technological advantage over their rivals, or to avoid falling behind, often lead to excessive and destabilizing arms buildups. A race in autonomy poses a particular danger because the consequences of investing machines with increased intelligence and decision-making authority are largely unknown and could prove catastrophic. In their haste to match the presumed progress of likely adversaries, states might field robotic weapons with considerable autonomy well before their abilities and limitations have been fully determined, resulting in unintended fatalities or uncontrolled escalation.

Supposedly, those risks would be minimized by maintaining some degree of human control over all such machines, but the race to field increasingly capable robotic weapons could result in ever-diminishing oversight. “Despite [the Defense Department’s] insistence that a ‘man in the loop’ capability will always be part of RAS systems,” the CRS noted in 2018, “it is possible if not likely, that the U.S. military could feel compelled to develop…fully autonomous weapon systems in response to comparable enemy ground systems or other advanced threat systems that make any sort of ‘man in the loop’ role impractical.”8

Assessing the Risks

Given the likelihood that China, Russia, the United States, and other nations will deploy increasingly autonomous robotic weapons in the years ahead, policymakers must identify and weigh the potential risks of such deployments. These include not only the potential for accident and unintended escalation, as would be the case with any new weapons that are unleashed on the battlefield, but also a wide array of moral, ethical, and legal concerns arising from the diminishing role of humans in life-and-death decision-making.

The potential dangers associated with the deployment of AI-empowered robotic weapons begin with the fact that much of the technology involved is new and untested under the conditions of actual combat, where unpredictable outcomes are the norm. For example, it is one thing to test self-driving cars under controlled conditions with human oversight; it is another to let such vehicles loose on busy highways. If that self-driving vehicle is covered with armor, equipped with a gun, and released on a modern battlefield, algorithms can never anticipate all the hazards and mutations of combat, no matter how well “trained” the algorithms governing the vehicle’s actions may be. In war, accidents and mishaps, some potentially catastrophic, are almost inevitable.

Extensive testing of AI image-classification algorithms has shown that such systems can easily be fooled by slight deviations from standardized representations—in one experiment, a turtle was repeatedly identified as

a rifle9—and are vulnerable to trickery, or “spoofing,” as well as hacking by adversaries.

Former Navy Secretary Richard Danzig, who has studied the dangers of employing untested technologies on the battlefield, has been particularly outspoken in cautioning against the premature deployment of AI-empowered weaponry. “Unfortunately, the uncertainties surrounding the use and interaction of new military technologies are not subject to confident calculation or control,” he wrote in 2018.10

This danger is all the more acute because, on the current path, autonomous weapons systems will be accorded ever-greater authority to make decisions on the use of lethal force in battle. Although U.S. authorities insist that human operators will always be involved when life-and-death decisions are made by armed robots, the trajectory of technology is leading to an ever-diminishing human role in that capacity, heading eventually to a time when humans are uninvolved entirely. This could occur as a deliberate decision, such as when a drone is set free to attack targets fitting a specified appearance (“adult male armed with gun”), or as a conditional matter, as when drones are commanded to fire at their discretion if they lose contact with human controllers. A human operator is somehow involved, by launching the drones on those missions, but no human is ordering the specific lethal attack.

Maintaining Ethical Norms

This poses obvious challenges because virtually all human ethical and religious systems view the taking of a human life, whether in warfare or not, as a supremely moral act requiring some valid justification. Humans, however imperfect, are expected to abide by this principle, and most societies punish those who fail to do so. Faced with the horrors of war, humans have sought to limit the conduct of belligerents in wartime, aiming to prevent cruel and excessive violence. Beginning with the Hague Convention of 1898 and in subsequent agreements forged in Geneva after World War I, international jurists have devised a range of rules, collectively, the laws of war, proscribing certain behaviors in armed conflict, such as the use of poisonous gas. Following World War II and revelations of the Holocaust, diplomats adopted additional protocols to the Hague and Geneva conventions intended to better define the obligations of belligerents in sparing civilians from the ravages of war, measures generally known as international humanitarian law. So long as humans remain in control of weapons, in theory they can be held accountable under the laws of war and international humanitarian law for any violations committed when using those devices. What happens when a machine makes the decision to take a life and questions arise over the legitimacy of that action? Who is accountable for any crimes found to occur, and how can a chain of responsibility be determined?

These questions arise with particular significance regarding two key aspects of international humanitarian law, the requirement for distinction and proportionality in the use of force against hostile groups interspersed with civilian communities. Distinction requires warring parties to discriminate between military and civilian objects and personnel during the course of combat and spare the latter from harm to the greatest extent possible. Proportionality requires militaries to apply no more force than needed to achieve the intended objective, while sparing civilian personnel and property from unnecessary collateral damage.11

These principles pose a particular challenge to fully autonomous weapons systems because they require a capacity to make fine distinctions in the heat of battle. It may be relatively easy in a large tank-on-tank battle, for example, to distinguish military from civilian vehicles; but in many recent conflicts, enemy combatants have armed ordinary pickup trucks and covered them with a tarpaulins, making them almost indistinguishable from civilian vehicles. Perhaps a hardened veteran could spot the difference, but an intelligent robot? Unlikely. Similarly, how does one gauge proportionality when attempting to attack enemy snipers firing from civilian-occupied tenement buildings? For robots, this could prove an insurmountable challenge.

These principles pose a particular challenge to fully autonomous weapons systems because they require a capacity to make fine distinctions in the heat of battle. It may be relatively easy in a large tank-on-tank battle, for example, to distinguish military from civilian vehicles; but in many recent conflicts, enemy combatants have armed ordinary pickup trucks and covered them with a tarpaulins, making them almost indistinguishable from civilian vehicles. Perhaps a hardened veteran could spot the difference, but an intelligent robot? Unlikely. Similarly, how does one gauge proportionality when attempting to attack enemy snipers firing from civilian-occupied tenement buildings? For robots, this could prove an insurmountable challenge.

Advocates and critics of autonomous weaponry disagree over whether such systems can be equipped with algorithms sufficiently adept to distinguish between targets to satisfy the laws of war. “Humans possess the unique capacity to identify with other human beings and are thus equipped to understand the nuances of unforeseen behavior in ways that machines, which must be programmed in advance, simply cannot,” analysts from Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the International Human Rights Clinic of Harvard Law School wrote in 2016.12

Another danger arises from the speed with which automated systems operate, along with plans for deploying autonomous weapons systems in coordinated groups, or swarms. The Pentagon envisions a time when large numbers of drone ships and aircraft are released to search for enemy missile-launching submarines and other critical assets, including mobile ballistic missile launchers. At present, U.S. adversaries rely on those missile systems to serve as an invulnerable second-strike deterrent to a U.S. disarming first strike. Should Russia or China ever perceive that swarming U.S. drones threaten the survival of their second-strike systems, those countries could feel pressured to launch their missiles when such swarms are detected, lest they lose their missiles to a feared U.S. first strike.

Strategies for Control

Since it first became evident that strides in AI would permit the deployment of increasingly autonomous weapons systems and that the major powers were seeking to exploit those breakthroughs for military advantage, analysts in the arms control and human rights communities, joined by sympathetic diplomats and others, have sought to devise strategies for regulating such systems or banning them entirely.

Since it first became evident that strides in AI would permit the deployment of increasingly autonomous weapons systems and that the major powers were seeking to exploit those breakthroughs for military advantage, analysts in the arms control and human rights communities, joined by sympathetic diplomats and others, have sought to devise strategies for regulating such systems or banning them entirely.

As part of that effort, parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), a 1980 treaty that restricts or prohibits the use of particular types of weapons that are deemed to cause unnecessary suffering to combatants or to harm civilians indiscriminately, established a group of governmental experts to assess the dangers posed by fully autonomous weapons systems and to consider possible control mechanisms. Some governments also have sought to address these questions independently, while elements of civil society have entered the fray.

Out of this process, some clear strategies for limiting these systems have emerged. The first and most unequivocal would be the adoption under the CCW of a legally binding international ban on the development, deployment, or use of fully autonomous weapons systems. Such a ban could come in the form a new CCW protocol, a tool used to address weapon types not envisioned in the original treaty, as has happened with a 1995 ban on blinding laser weapons and a 1996 measure restricting the use of mines, booby traps, and other such devices.13 Two dozen states, backed by civil society groups such as the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, have called for negotiating an additional CCW protocol banning fully autonomous weapons systems altogether.

Proponents of such a measure say it is the only way to avoid inevitable violations of international humanitarian law and that a total ban would help prevent the unintended escalation of conflict. Opponents argue that autonomous weapons systems can be made intelligent enough to overcome concerns regarding international humanitarian law, so no barriers should be placed on their continued development. As deliberations by CCW member states are governed by consensus, a few states with advanced robotic projects, notably Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, have so far blocked consideration of such a protocol.

Another proposal, advanced by representatives of France and Germany at the experts’ meetings, is the adoption of a political declaration affirming the principle of human control over weapons of war accompanied by a nonbinding code of conduct. Such a measure, possibly in the form of a UN General Assembly resolution, would require human responsibility over fully autonomous weapons systems at all times to ensure compliance with the laws of war and international humanitarian law and would entail certain assurances to this end. The code could establish accountability for states committing any misdeeds with fully autonomous weapons systems in battle and require that these weapons retain human oversight to disable the device if it malfunctions. States could be required to subject proposed robotic systems to predeployment testing, in a thoroughly transparent fashion, to ensure they were compliant with these constraints.14

Those who favor a legally binding ban under the CCW claim this alternative would fail to halt the arms race in fully autonomous weapons systems and would allow some states to field weapons with dangerous and unpredictable capabilities. Others say a total ban may not be achievable and argue that a nonbinding measure of this sort is the best option available.

Yet another approach gaining attention is a concentrated focus on the ethical dimensions of fielding fully autonomous weapons systems. This outlook holds that international law and common standards of ethical practice ordain that only humans possess the moral capacity to justify taking another human’s life and that machines can never be vested with that power. Proponents of this approach point to the Martens clause of the Hague Convention of 1899, also inscribed in Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions, stating that even when not covered by other laws and treaties, civilians and combatants “remain under the protection and authority of the principles of international law derived from established custom, from the principles of humanity and from the dictates of human conscience.” Opponents of fully autonomous weapons systems claim that such weapons, by removing humans from life-and-death decision-making, are inherently contradicting principles of humanity and dictates of human conscience and so should be banned. Reflecting awareness of this issue, the Defense Department has reportedly begun to develop a set of guiding principles for the “safe, ethical, and responsible use” of AI and autonomous weapons systems by the military services.

Today, very few truly autonomous robotic weapons are in active combat use, but many countries are developing and testing a wide range of machines possessing high degrees of autonomy. Nations are determined to field these weapons quickly, lest their competitors outpace them in an arms race in autonomy. Diplomats and policymakers must seize this moment before fully autonomous weapons systems become widely deployed to weigh the advantages of a total ban and consider other measures to ensure they will never be used to commit unlawful acts or trigger catastrophic escalation.

ENDNOTES

1. For a summary of such efforts, see Congressional Research Service (CRS), “U.S. Ground Forces Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) and Artificial Intelligence: Considerations for Congress,” R45392, November 20, 2018.

2. U.S. Department of Defense, “Autonomy in Weapons Systems,” directive no. 3000.09 (November 21, 2012).

3. For more information on the Aegis Combat System, see Paul Scharre, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018).

4. For more information on the Harpy drone, see ibid.

5. U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, “The U.S. Army Robotic and Autonomous Systems Strategy,” March 2017, p. 3, https://www.tradoc.army.mil/Portals/14/Documents/RAS_Strategy.pdf.

6. Mark Mazzara, “Army Ground Robotics Overview: OSD Joint Technology Exchange Group,” April 24, 2018, https://jteg.ncms.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/02-PM-FP-Robotics-Overview-JTEG.pdf. See James Langford, “Lockheed Wins Army Contract for Self-Driving Military Convoy Systems,” Washington Examiner, July 30, 2018.

7. See David B. Larter, “U.S. Navy Moves Toward Unleashing Killer Robot Ships on the World’s Oceans,” Defense News, January 15, 2019.

8. CRS, “U.S. Ground Forces Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) and Artificial Intelligence.”

9. Anish Athalye et al., “Fooling Neural Networks in the Physical World With 3D Adversarial Objects,” LabSix, October 31, 2017, https://www.labsix.org/physical-objects-that-fool-neural-nets/.

10. Richard Danzig, “Technology Roulette: Managing Loss of Control as Many Militaries Pursue Technological Superiority,” Center for a New American Security, June 2018, p. 5, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNASReport-Technology-Roulette-DoSproof2v2.pdf.

11. See CRS, “Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems: Issues for Congress,” R44466,

April 14, 2016.

12. Human Rights Watch and International Human Rights Clinic, “Making the Case: The Dangers of Killer Robots and the Need for a Preemptive Ban,” December 2016, p. 5, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/arms1216_web.pdf.

13. UN Office at Geneva, “The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons,” n.d., https://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/4F0DEF093B4860B4C1257180004B1B30 (accessed 9 February 2019).

14. See Group of Governmental Experts Related to Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS), “Emerging Commonalities, Conclusions and Recommendations,” August 2018, https://www.unog.ch/unog/website/assets.nsf/7a4a66408b19932180256ee8003f6114/eb4ec9367d3b63b1c12582fd0057a9a4/$FILE/GGE%20LAWS%20August_EC,%20C%20and%20Rs_final.pdf.

Michael T. Klare is a professor emeritus of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association. This is the second in the “Arms Control Tomorrow” series, in which he considers disruptive emerging technologies and their implications for war-fighting and arms control. This installment provides an assessment of autonomous weapons systems development and prospects, the dangers they pose, and possible strategies for their control.

Originally designated by DARPA as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle (ACTUV), Sea Hunter is designed to travel the oceans for months at a time with no onboard crew, searching for enemy submarines and reporting their location and findings to remote human operators. If this concept proves viable (Sea Hunter recently completed a round trip from San Diego, Calif., to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with no crew) swarms of ACTUVs may be deployed worldwide, some capable of attacking submarines on their own, in accordance with sophisticated algorithms.

Originally designated by DARPA as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle (ACTUV), Sea Hunter is designed to travel the oceans for months at a time with no onboard crew, searching for enemy submarines and reporting their location and findings to remote human operators. If this concept proves viable (Sea Hunter recently completed a round trip from San Diego, Calif., to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with no crew) swarms of ACTUVs may be deployed worldwide, some capable of attacking submarines on their own, in accordance with sophisticated algorithms. Few weapons in active service presently exhibit all of these characteristics. Many militaries employ close-in naval defense weapons such as the U.S. Phalanx gun system that can fire autonomously when a ship is under attack by enemy planes or missiles. Yet, such systems cannot independently search for and strike enemy assets on their own, and human operators are always present to assume control if needed.

Few weapons in active service presently exhibit all of these characteristics. Many militaries employ close-in naval defense weapons such as the U.S. Phalanx gun system that can fire autonomously when a ship is under attack by enemy planes or missiles. Yet, such systems cannot independently search for and strike enemy assets on their own, and human operators are always present to assume control if needed. These principles pose a particular challenge to fully autonomous weapons systems because they require a capacity to make fine distinctions in the heat of battle. It may be relatively easy in a large tank-on-tank battle, for example, to distinguish military from civilian vehicles; but in many recent conflicts, enemy combatants have armed ordinary pickup trucks and covered them with a tarpaulins, making them almost indistinguishable from civilian vehicles. Perhaps a hardened veteran could spot the difference, but an intelligent robot? Unlikely. Similarly, how does one gauge proportionality when attempting to attack enemy snipers firing from civilian-occupied tenement buildings? For robots, this could prove an insurmountable challenge.

These principles pose a particular challenge to fully autonomous weapons systems because they require a capacity to make fine distinctions in the heat of battle. It may be relatively easy in a large tank-on-tank battle, for example, to distinguish military from civilian vehicles; but in many recent conflicts, enemy combatants have armed ordinary pickup trucks and covered them with a tarpaulins, making them almost indistinguishable from civilian vehicles. Perhaps a hardened veteran could spot the difference, but an intelligent robot? Unlikely. Similarly, how does one gauge proportionality when attempting to attack enemy snipers firing from civilian-occupied tenement buildings? For robots, this could prove an insurmountable challenge. Since it first became evident that strides in AI would permit the deployment of increasingly autonomous weapons systems and that the major powers were seeking to exploit those breakthroughs for military advantage, analysts in the arms control and human rights communities, joined by sympathetic diplomats and others, have sought to devise strategies for regulating such systems or banning them entirely.

Since it first became evident that strides in AI would permit the deployment of increasingly autonomous weapons systems and that the major powers were seeking to exploit those breakthroughs for military advantage, analysts in the arms control and human rights communities, joined by sympathetic diplomats and others, have sought to devise strategies for regulating such systems or banning them entirely. In January 2019, the Trump administration released the results of the last of its planned major strategic policy reviews, the Missile Defense Review, to examine U.S. “policies, strategies, and capabilities…to counter the expanding missile threats posed by rogue states and revisionist powers.” It is the first such review since the Obama administration conducted one in 2010. To assess how U.S. missile defense goals and programs are evolving, Arms Control Today invited two experts to comment on the review: Laura Grego, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, and Elaine Bunn, a consultant with extensive government experience in missile defense policy.

In January 2019, the Trump administration released the results of the last of its planned major strategic policy reviews, the Missile Defense Review, to examine U.S. “policies, strategies, and capabilities…to counter the expanding missile threats posed by rogue states and revisionist powers.” It is the first such review since the Obama administration conducted one in 2010. To assess how U.S. missile defense goals and programs are evolving, Arms Control Today invited two experts to comment on the review: Laura Grego, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, and Elaine Bunn, a consultant with extensive government experience in missile defense policy. Some of the administration’s preferences were apparent before the report was released in January. President Donald Trump's budget requests in fiscal years 2018 and 2019 directed the expansion of existing theater and strategic ballistic missile defense systems. The 2018 National Defense Strategy and 2017 National Security Strategy, outlined missile defense goals broadly consistent with those of the Obama administration in its 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review

Some of the administration’s preferences were apparent before the report was released in January. President Donald Trump's budget requests in fiscal years 2018 and 2019 directed the expansion of existing theater and strategic ballistic missile defense systems. The 2018 National Defense Strategy and 2017 National Security Strategy, outlined missile defense goals broadly consistent with those of the Obama administration in its 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review Surprisingly, the review delayed decisions on a number of issues. Although the report discusses different boost-phase ballistic missile defense ideas, including space-based interceptors and new interceptors for F-35 Lightning II aircraft, it does not begin programs of record for them. Rather, it orders the Pentagon to conduct six-month studies on them and continues research and development on the existing drone-based, directed-energy, boost-phase program.

Surprisingly, the review delayed decisions on a number of issues. Although the report discusses different boost-phase ballistic missile defense ideas, including space-based interceptors and new interceptors for F-35 Lightning II aircraft, it does not begin programs of record for them. Rather, it orders the Pentagon to conduct six-month studies on them and continues research and development on the existing drone-based, directed-energy, boost-phase program. Over the past two decades, three intersecting questions have informed missile defense efforts. First, is the objective to defend the U.S. homeland or forces abroad and allies? Second, what types of missiles are U.S. defenses intended to defeat? Historically, the targets were ballistic missiles, but the new review includes cruise missiles and hypersonic glide vehicles. Third, which countries’ missiles are U.S. defenses designed to destroy? Earlier U.S. missile defense policies aimed to protect the U.S. homeland and areas abroad from North Korea and Iran, to provide regional but not homeland defense against Chinese threats; and to offer neither homeland nor, in practice, regional defense against Russian missiles.

Over the past two decades, three intersecting questions have informed missile defense efforts. First, is the objective to defend the U.S. homeland or forces abroad and allies? Second, what types of missiles are U.S. defenses intended to defeat? Historically, the targets were ballistic missiles, but the new review includes cruise missiles and hypersonic glide vehicles. Third, which countries’ missiles are U.S. defenses designed to destroy? Earlier U.S. missile defense policies aimed to protect the U.S. homeland and areas abroad from North Korea and Iran, to provide regional but not homeland defense against Chinese threats; and to offer neither homeland nor, in practice, regional defense against Russian missiles. As for change, the report discusses plans to test this interceptor against an ICBM by 2020 to assess its potential to provide an additional layer for homeland defense against rogue states’ long-range missiles. Russia will likely complain that such testing will enable NATO sites with SM-3 Block IIA interceptors to intercept Russian ICBMs.

As for change, the report discusses plans to test this interceptor against an ICBM by 2020 to assess its potential to provide an additional layer for homeland defense against rogue states’ long-range missiles. Russia will likely complain that such testing will enable NATO sites with SM-3 Block IIA interceptors to intercept Russian ICBMs. The United States and Russia have each announced they will suspend adherence to the treaty, and Washington has formally announced its plans to withdraw from the pact in early August.

The United States and Russia have each announced they will suspend adherence to the treaty, and Washington has formally announced its plans to withdraw from the pact in early August. Options for regulating weapons with nuclear and conventional capability. NATO in the 1960s and 1970s and Russia from 2000 to 2014 relied on nuclear weapons to balance their adversaries’ conventional advantage. It seems increasingly likely that the United States and NATO could respond in a similar way to the acquisition and deployment of more conventionally armed weapons by Russia. Consequently, arms control no longer can be limited to nuclear weapons.

Options for regulating weapons with nuclear and conventional capability. NATO in the 1960s and 1970s and Russia from 2000 to 2014 relied on nuclear weapons to balance their adversaries’ conventional advantage. It seems increasingly likely that the United States and NATO could respond in a similar way to the acquisition and deployment of more conventionally armed weapons by Russia. Consequently, arms control no longer can be limited to nuclear weapons. There is little reason to believe that Russia will want to engage in an arms control dialogue with the United States, although it will declare its readiness to do so. The likelihood of such dialogue was further reduced by Putin’s announcement that Moscow will no longer take a proactive approach, although all its earlier initiatives will remain on the table.4 Effectively, he has said that Russia will sit patiently and wait for others to come to it to ask, even beg, for arms control. The delay in arms control interaction will be driven not just by Washington, but equally by Moscow.

There is little reason to believe that Russia will want to engage in an arms control dialogue with the United States, although it will declare its readiness to do so. The likelihood of such dialogue was further reduced by Putin’s announcement that Moscow will no longer take a proactive approach, although all its earlier initiatives will remain on the table.4 Effectively, he has said that Russia will sit patiently and wait for others to come to it to ask, even beg, for arms control. The delay in arms control interaction will be driven not just by Washington, but equally by Moscow. After earning his doctorate from Columbia University and completing a short stint at the U.S. Department of Defense, Houck joined the fledgling U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in 1962. It was just a year after the independent agency was created with a mission of managing U.S. participation in international arms control negotiations, among many other activities.

After earning his doctorate from Columbia University and completing a short stint at the U.S. Department of Defense, Houck joined the fledgling U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in 1962. It was just a year after the independent agency was created with a mission of managing U.S. participation in international arms control negotiations, among many other activities.

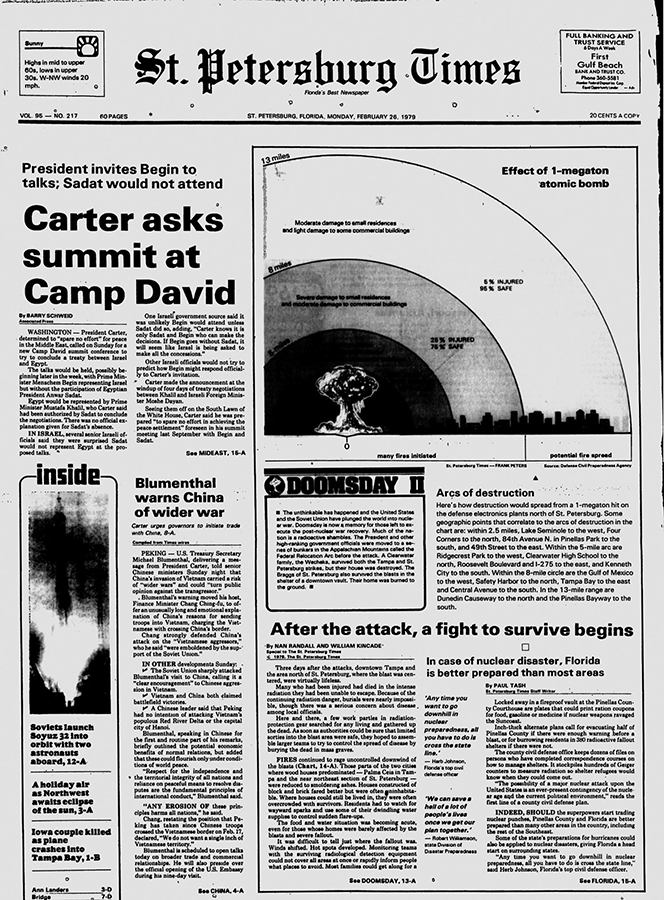

In late 1978, editors at the Florida's St. Petersburg Times newspaper decided to run a large feature on the effects of a nuclear blast. Knowing little about the technical aspects of such an event, they sought guidance.

In late 1978, editors at the Florida's St. Petersburg Times newspaper decided to run a large feature on the effects of a nuclear blast. Knowing little about the technical aspects of such an event, they sought guidance. We see the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons as the global version of our nuclear-free zone. We hope our region will be as strong in its support for the prohibition treaty as we have been for the Treaty of Rarotonga.

We see the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons as the global version of our nuclear-free zone. We hope our region will be as strong in its support for the prohibition treaty as we have been for the Treaty of Rarotonga. German Chancellor Angela Merkel persuaded Trump to hold off on withdrawal for 60 days to give diplomacy one last chance, but Washington and Moscow spent more time assigning blame for the crisis than discussing ways to resolve their concerns. Those issues revolve around the years-old U.S. charges that Russia developed and deployed a treaty-prohibited, ground-launched, nuclear-capable cruise missile, known as the 9M729, and Russian countercharges that the United States is violating the treaty. (

German Chancellor Angela Merkel persuaded Trump to hold off on withdrawal for 60 days to give diplomacy one last chance, but Washington and Moscow spent more time assigning blame for the crisis than discussing ways to resolve their concerns. Those issues revolve around the years-old U.S. charges that Russia developed and deployed a treaty-prohibited, ground-launched, nuclear-capable cruise missile, known as the 9M729, and Russian countercharges that the United States is violating the treaty. ( “I’d much rather do it right than do it fast,” Trump told reporters following the meeting, but he did not provide any details on the next steps in the negotiating process.

“I’d much rather do it right than do it fast,” Trump told reporters following the meeting, but he did not provide any details on the next steps in the negotiating process. The ultimate impact of the review remains to be seen, given the divergence between U.S. President Donald Trump’s description of U.S. missile defense objectives and those described in the report. Uncertainty was also generated by the report’s call for several follow-up studies and by misgivings from some members of Congress.

The ultimate impact of the review remains to be seen, given the divergence between U.S. President Donald Trump’s description of U.S. missile defense objectives and those described in the report. Uncertainty was also generated by the report’s call for several follow-up studies and by misgivings from some members of Congress.