March 2021

By George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi

When adversaries consider each other’s capabilities and intentions, they focus on whichever is most threatening. With nuclear weapons, force posture and operational practices are usually considered more important than what leaders declare are circumstances in which they would consider unleashing nuclear weapons. Still, nuclear policies and forces require rationales to guide them. Declaratory policy articulates such rationales, even if decision-making on the development of nuclear weapons and other capabilities sometimes has a bureaucratic-political-economic logic of its own.

There is no perfect or nonproblematic nuclear weapons declaratory policy. One that sets the threshold for nuclear use too low invites international and perhaps domestic recriminations, along with arms racing and crisis instability. “These people are a menace,” competitors will say. “We must build up to stop them.” Nuclear disarmament advocates and non-nuclear-weapon states will say, “These people are a menace; we must disarm them.”

There is no perfect or nonproblematic nuclear weapons declaratory policy. One that sets the threshold for nuclear use too low invites international and perhaps domestic recriminations, along with arms racing and crisis instability. “These people are a menace,” competitors will say. “We must build up to stop them.” Nuclear disarmament advocates and non-nuclear-weapon states will say, “These people are a menace; we must disarm them.”

A declaratory policy that nearly rules out the use of nuclear weapons may make domestic opponents and dependent allies fear that adversaries will behave more aggressively. “When push comes to shove, this administration will lack the resolve to stop a determined, fast-moving aggressor,” critics will charge.

Rather than seeming too permissive or too restrictive in describing the circumstances surrounding nuclear use, some nuclear-armed states often take refuge in an ambiguous public declaratory policy that leaves much to the interpretation of the audience. The United States has done this, although less so than the other nuclear-armed Western democracies that might use ambiguity to avoid criticism: the United Kingdom, France, and Israel. The Obama and Trump administrations nuclear posture reviews, in 20101 and 20182 respectively, declared rather vaguely that the United States “would only consider the employment of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States, its allies and partners.”

As the Biden administration prepares its own review of nuclear policy, various actors and interests are pushing different options for defining when the United States would or would not consider using nuclear weapons. On the “permissive” side are champions of the Trump administration’s declaratory policy, which added a coda that extreme circumstances “could include significant non-nuclear strategic attacks” against the United States or its allies and partners. On the “restrictive” side are many U.S. activists and analysts, along with much of the rest of the world, who want the United States to declare a no-first-use policy.

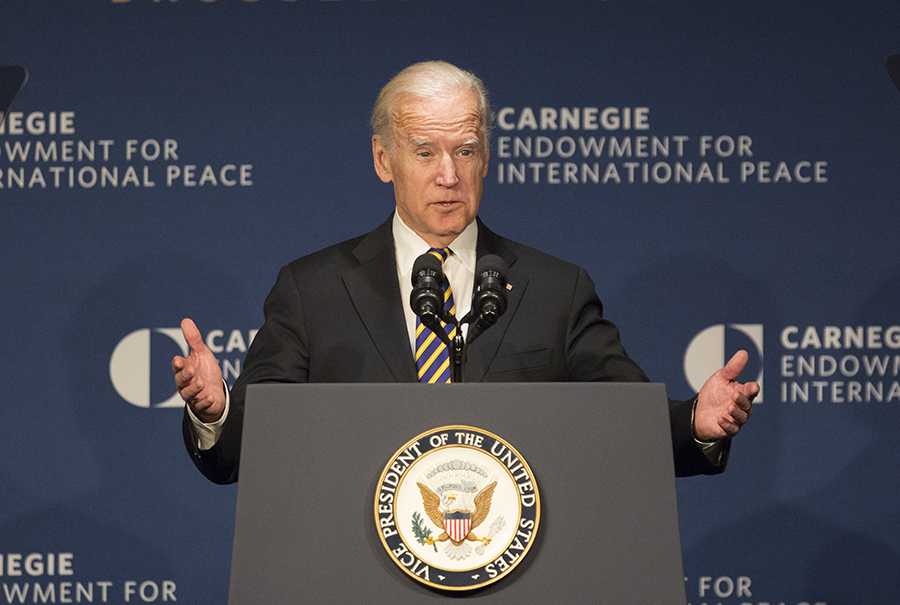

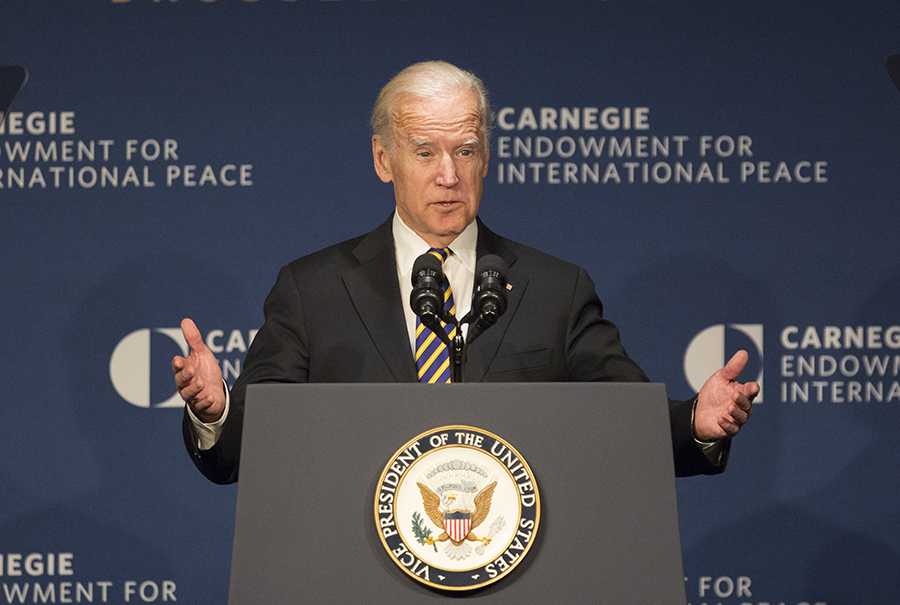

In a major speech on nuclear security issues on January 11, 2017, Vice President Joe Biden offered his own formulation:

Given our non-nuclear capabilities and the nature of today’s threats, it’s hard to envision a plausible scenario in which the first use of nuclear weapons by the United States would be necessary or make sense. President Obama and I are confident we can deter and defend ourselves and our allies against non-nuclear threats through other means. The next administration will put forward its own policies. But seven years after the Nuclear Posture Review [NPR] charge, the President and I strongly believe we have made enough progress that deterring and if necessary, retaliating against a nuclear attack should be the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.3

Unsurprisingly then, the 2020 Democratic Party platform declared “that the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal should be to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate against—a nuclear attack.”

After analyzing these options, there is an alternative closer to “just right”: a policy that posits a less ambiguous, higher threshold for U.S. employment of nuclear weapons than the Trump or Obama administrations did; is more prudent and alliance-cohering than a no-first-use policy would be; and is more adaptable to evolving threats than the sole-purpose policy would be. That policy would state that the United States would consider the use of nuclear weapons “only when no viable alternative exists to stop an existential attack against the United States, its allies, or partners.”

Such a formulation, called an existential threat policy (ETP), would reflect U.S. and allied interests better than the alternatives. By adhering more closely to the law of armed conflict than the current policy of “calculated ambiguity,” an ETP would better position the United States in political contests with Russia and China. By offering a logic of proportionality that any nation could justifiably use in defending itself or its allies, an ETP would raise the level of international debate over nuclear deterrence and disarmament.

Current Policy

U.S. officials choose to “retain some ambiguity regarding the precise circumstances that might lead to a U.S. nuclear response,” as the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) admits. Ambiguity spares presidents from making commitments based on hypothetical scenarios and preserves the flexibility to act based on the real-world situation at the time. Ambiguity also can help alleviate allies’ fears that the United States might abandon them when they are under attack.

In addition, ambiguity is a tempting way to try to inflate the effects of deterrence. The arguably low threshold of “extreme circumstances” in the 2010 and 2018 reviews could make adversaries more cautious or restrained in using any kind of force than they would be otherwise. This seems to be the French and UK approach too, making potential adversaries guess what their threshold is.

Yet, this temptation to inflate the currency of nuclear weapons comes with risk. Bitter experience shows that possessing nuclear weapons does not deter all forms of aggression or coercion, nor does it guarantee winning wars. If nuclear deterrence did work against all forms of aggression and guarantee victory in war, many more states would want to acquire these weapons, which poses other risks. Overreliance on nuclear deterrence also can create a strategic and moral hazard of decreasing the resolve of politicians and polities to prevent conflicts at the outset and to acquire conventional and other defenses to deter or defeat less-than-existential threats.

Yet, this temptation to inflate the currency of nuclear weapons comes with risk. Bitter experience shows that possessing nuclear weapons does not deter all forms of aggression or coercion, nor does it guarantee winning wars. If nuclear deterrence did work against all forms of aggression and guarantee victory in war, many more states would want to acquire these weapons, which poses other risks. Overreliance on nuclear deterrence also can create a strategic and moral hazard of decreasing the resolve of politicians and polities to prevent conflicts at the outset and to acquire conventional and other defenses to deter or defeat less-than-existential threats.

The United States and others should be clearer in recognizing that nuclear use can be justified strategically and legally only when the threat to be deterred or stopped is proportionate to the likely consequence of nuclear weapons use. As the “Department of Defense Law of War Manual” declares, “[T]he overall goal of the State in resorting to war should not be outweighed by the harm that the war is expected to produce.”4

This argument for more clarity about the height of the nuclear threshold becomes more urgent in the aftermath of the Trump administration’s declaration that the United States could rightly consider nuclear use in response to “significant non-nuclear strategic attacks.” Presumably, this means attacks involving conventional, cyber-, chemical, or biological weapons. The 2018 NPR report elaborated somewhat that targets warranting potential nuclear response include “the U.S., allied, or partner civilian population or infrastructure, and attacks on U.S. or allied nuclear forces, their command and control, or warning and attack assessment capabilities.”

There are ominous tensions here. The United States is committed to “adhere to the law of armed conflict…in the initiation and conduct of nuclear operations,” in the words of the 2018 NPR report. How would the legal criteria of necessity, distinction (not targeting civilian objects or personnel), and proportionality be met in using nuclear weapons to defeat attacks by conventional, cyber-, chemical, or biological weapons?

More importantly, adversary leaders might perceive the 2018 declaratory policy as justifying intentions and capabilities to conduct disarming first strikes on them. Defense officials in these countries already assume in the worst case that U.S. conventional, cyber-, and nuclear forces will be preemptively employed to destroy their nuclear deterrents, with missile defenses meant to block whatever survives. The widened ambiguity of declaratory policy will only affirm worst-case thinking. This may drive or rationalize these states’ development and deployment of more, technologically better nuclear weapons and operational plans to avoid destruction or disablement by the United States. The arms race and crisis instabilities that result are arguably in no one’s interest.

No-First-Use Policy

The concept of pledging not to be the first to initiate nuclear weapons use has been a feature of the nuclear policy debate for decades. It has long been an element of the official public policies of China and India. In recent years, U.S. policymakers, encouraged by other countries and civil society groups, have once again considered whether to adopt a no-first-use policy, most recently the Obama administration in 2016. In its most restrictive form, such a policy would pledge the United States to never use nuclear weapons first in a conflict. The goals are to establish or clarify that the United States would not start a nuclear war and to reduce politically the salience of nuclear weapons nationally and globally.

Informed advocates argue that there are “few, if any”5 scenarios in which U.S. first use would constitute a necessary or credible threat against Russia, China, or North Korea, the three states currently “eligible” for potential first use of nuclear weapons under U.S. policy. Yet, allies, partners, adversaries, and U.S. policymakers understandably will and should focus on the word “few.” Does it mean that there are indeed some scenarios in which the first use of nuclear weapons would be a viable last option for the United States to defeat an adversary’s strategic non-nuclear aggression or imminent nuclear attack? If so, what would Washington plan to do in these contingencies if it subscribed to a no-first-use policy?

For example, if North Korea, which has nuclear weapons that might be able to penetrate U.S. missile defenses, were detected preparing to carry out orders to launch nuclear weapons against U.S. allies or the homeland, should the United States forswear the option of using nuclear weapons first to interdict such an attack if there was no other way to do so? Beyond the North Korean scenario, a few other hypothetical cases are evident, involving Russia and European allies, and China vis-à-vis Taiwan. These adversaries also could weaponize biological technologies and inflict chaos and massive casualties on allied and U.S. populations, making U.S. leaders conclude that these governments and their militaries must be defeated immediately in ways that conventional weaponry could not accomplish. As horrific as chemical weapons use can be, it is extremely difficult to see how they would pose an existential threat necessitating U.S. nuclear use.

Allies are an important audience for U.S. declaratory policy. They are more likely than adversaries to believe U.S. policy statements and plan accordingly. Yet, allies are not uniform. Some may oppose any nuclear weapons use, particularly in and around their countries. Others may see a no-first-use policy more broadly as a sign of U.S. withdrawal from its historic commitments to alliances, an issue that became more salient in recent years. Still others, privately at least, think a no-first-use policy would weaken collective deterrence of Russia or China without securing any restraint from them in return. Any consideration of declaratory policy change must involve sustained, wide-ranging consultations with allies.

Ultimately, Russia and China, like the United States, pay more attention to capabilities than declared intentions. A no-first-use declaration would be relatively meaningless to Moscow and Beijing without reductions in the weapons that are most tied to such a policy. Yet, the political capital that a president would expend to push this declaration through the U.S. system and allied governments would leave little to overcome traditional resistance to alter the force posture. Opponents, including vocal members of Congress, would produce quotes from current and recently retired military leaders decrying the change and accusing the president of being weak on national security and the threats from Russia and China. To balance the perceived diminution of nuclear deterrence, the administration would face added pressure, including from Democratic members of Congress, to increase spending on nuclear modernization or at least not to pause or cut controversial programs under review.6 Allied governments in Europe, Japan, and Australia would fret that this policy shift exacerbates their loss of confidence in U.S. leadership—“even the Trump administration did not do this,” some will say.

Ultimately, Russia and China, like the United States, pay more attention to capabilities than declared intentions. A no-first-use declaration would be relatively meaningless to Moscow and Beijing without reductions in the weapons that are most tied to such a policy. Yet, the political capital that a president would expend to push this declaration through the U.S. system and allied governments would leave little to overcome traditional resistance to alter the force posture. Opponents, including vocal members of Congress, would produce quotes from current and recently retired military leaders decrying the change and accusing the president of being weak on national security and the threats from Russia and China. To balance the perceived diminution of nuclear deterrence, the administration would face added pressure, including from Democratic members of Congress, to increase spending on nuclear modernization or at least not to pause or cut controversial programs under review.6 Allied governments in Europe, Japan, and Australia would fret that this policy shift exacerbates their loss of confidence in U.S. leadership—“even the Trump administration did not do this,” some will say.

In sum, for the purposes of reducing current destabilizing dynamics among the United States, Russia, and China, pursuing a no-first-use declaratory policy would do much less good than negotiating limits on offensive and defensive systems that exacerbate arms racing and crisis instability.

Sole-Purpose Policy

Another alternative is to declare, in the words of the 2020 Democratic Party platform, “that the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal should be to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate against—a nuclear attack.” A third option would operationalize Biden’s January 2017 formulation, which goes slightly further than “sole purpose” and comes close to a no-first-use policy. This formulation would leave open the possibility of employing nuclear weapons if it were the only way to preempt an imminent nuclear attack by a country such as North Korea. It appears to rule out, however, in words anyway, use of nuclear weapons as a last resort against Russian or Chinese non-nuclear forces that were defeating U.S. and allied forces and threatening to inflict massive harm on their populations, perhaps with biological weapons. A U.S. administration that adopted a sole-purpose policy would need to demonstrate that NATO and U.S. allies and partners in Asia were significantly improving their conventional military capabilities, their resilience, and their overall cooperation and cohesion to deter, defeat, and survive major conventional aggression and possible biological weapons attacks by Russia, China, and North Korea. Until that is accomplished, declaring a sole-purpose policy would risk straining U.S.-allied relations.

Existential Threat Policy

Despite the flaws of alternatives such as no-first-use and sole-purpose policies, U.S. declaratory policy should not remain the same. The threshold of “extreme circumstances” to defend “vital interests” is too ambiguous and, depending how it is interpreted, too low to serve the physical, strategic, political, and legal interests of the United States and allied and partner nations.

The potential, perhaps likely, consequences of employing nuclear weapons against an adversary that can retaliate in kind are so threatening to the populations of the countries involved and to nonbelligerent nations that nuclear weapons should only be detonated when the alternative would be worse destruction. Thus, the United States should declare it would consider employing “nuclear weapons only when no viable alternative exists to stop an existential attack against the United States, its allies, or partners.”

An ETP would reflect a realistically restrained approach to the conduct of nuclear deterrence and war and would bring U.S. policy more in line with the law of armed conflict. It would be credible because it would not pledge the United States to forswear the right to use all legal7 and necessary means to forestall a threat to its existence or that of its allies, as no-first-use and sole-purpose policies might. It could improve international security by encouraging U.S. and allied publics to deploy and rely on non-nuclear means to defeat all but existential threats. It could be advantageous in international politics because this declaratory policy could be a defensible model for any nuclear-armed state to articulate.

Critics will argue that an ETP is ambiguous—what is an existential threat? This is a fair question, but an ETP would be significantly less ambiguous than the current policy’s thresholds of “extreme circumstances” and “vital interests.” Many forms of attack or coercion could create extreme circumstances and threaten what in that moment politicians and pundits would call vital interests, but many of those threats would not be as destructive as escalatory nuclear war would be. Something more than irony occurs when analysts criticize the ambiguity of an ETP but commending the even wider ambiguity in the current policy.

Reducing Ambiguity

Nuclear weapons should be used only when “no viable alternative” exists because the law of armed conflict requires that a chosen military action must be necessary to defeat a given threat. If less destructive alternatives, such as conventional strike capabilities, are available, then they must be pursued first. The same logic should apply to explosive yield of weapons too, as the lowest yield sufficient to disable or destroy a legitimate target should be used. An ETP also conforms better to the law of armed conflict requirement of proportionality because no one, including the United States, would be wise and justified to use nuclear weapons in response to an injury that is less grave than a potential nuclear war.

What is an existential threat? Obviously, nuclear attack on populations meets this criterion, as would a genocidal non-nuclear aggression, including a massively effective biological weapons attack. Other existential thresholds are more difficult to define.

The Trump administration, echoing many observers, suggested that a cyberattack that disabled large swaths of the U.S. electrical supply would be the sort of “significant non-nuclear strategic attack” that could cause the United States to employ nuclear weapons. Yet, cyberattacks are strategically attractive to adversaries and to the United States (e.g., Stuxnet) in part because they do not necessarily cause destruction or even irreversible damage, let alone widespread death. Moreover, there are many ways, which realistically do not exist against nuclear attack, that government, tech industries, electric utilities, and hospitals, for example, can and should prepare themselves to defend against and survive cyberattacks. Nevertheless, in a scenario in which a cyberattack inflicted as many deaths as the COVID-19 pandemic has, if the United States could with a 99.9 percent certainty attribute the cyberattack to the Kremlin, which would take considerable time, would it be legally and strategically justified in responding to the attack by ordering a nuclear strike against Russia? Which targets? What if China or North Korea were the villain in the same scenario?

Nuclear retaliation would not stop a cyberattack or undo its damage, but it could trigger more death and destruction among belligerent and nonbelligerent nations alike. Even the threat to use a nuclear response to a cyberattack against civilian infrastructure, which did not cause damage commensurate with that caused by nuclear weapons, could normalize other states’ or nonstate actors’ threats or use of nuclear weapons, including in response to U.S. cyber operations. Blurring cyberweapons and nuclear weapons thresholds also could encourage some states or nonstate actors to conduct “false flag” cyberattacks, for instance, by using leaked U.S., Russian, or Chinese malware, to catalyze conflict between the United States and Russia or the United States and China.

Would a non-nuclear attack that removed a government’s leadership pose an existential threat warranting nuclear retaliation? If the attacks of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, were backed by a nuclear-armed adversary and had succeeded somehow in overturning the judicially validated presidential election and illegally imposing a head of state, the regime-changing insurrection clearly would be an “extreme circumstance” that threatened a “vital interest” of the United States. Would anyone in their right mind say that using nuclear weapons in response was a tolerable thing to do, or the least bad of bad alternatives?

Law and common sense argue that nuclear use should be predicated on the scale of violence and destruction inflicted by an adversary, not merely on the “damage” to one’s own government. Threats that do not harm societies on a scale proportionate to the destruction caused by even a limited nuclear war should be countered by non-nuclear means, even if procuring such means would be more costly than acquiring additional or different nuclear weapons. Attempts to invoke nuclear threats to deter such attacks amounts to a bluff and a moral hazard because belief in the power of nuclear deterrence could lead governments to avoid spending on more usable defensive capabilities.

Nevertheless, a state with an ETP would be justified in considering nuclear use in response to attacks of any kind, including cyberattacks, on its nuclear command, control, and communication assets on land or in space. The judgment would depend crucially on whether the attacker was perceived to have the intention and capability to inflict further violence and destruction on the United States or allies on a scale warranting nuclear response. If so, an attempt to render the U.S. nuclear deterrent blind, deaf, and dumb could be an existential threat.

Critics may claim that an ETP would invite Russia or China to act maliciously up to this declared nuclear threshold, which is higher than “extreme circumstances.” The prudent response is to enhance non-nuclear defenses and nuclear command, control, and communication capabilities rather than to expand the role of nuclear weapons, especially with the risks that regional conflicts could escalate inadvertently to nuclear war.

Of course, bolstering U.S. capabilities, whether nuclear or non-nuclear, often prompts alarm and countervailing reactions in Russia and China. To forestall these reactions and build international support for its position, U.S. declaratory policy should make clear the U.S. willingness to negotiate arms control and disarmament arrangements that enhance stability for all concerned.

Conclusion

Ultimately, if the United States wishes to retain or restore its international leadership in a global nuclear order, its declaratory policy should be one that Americans and others would find relatively acceptable if other states adopted it. Because deterrence could fail, it would be folly for anyone to posit using nuclear weapons in situations where ensuing action-reaction dynamics would probably leave one and one’s allies and partners worse off than if nuclear weapons were not used. Conversely, it would be imprudent to promise not to use nuclear weapons when there appears to be no better alternative to defend the viability of one’s nation or allies.

An ETP would clarify to adversaries and allies better than today’s “calculated ambiguity” does that the United States will not be too quick to pull the nuclear trigger and must maintain other means necessary to defeat the most probable forms of coercion or aggression. It would signal better than a no-first-use or sole-purpose policy that the United States recognizes that Russia, China, and North Korea still need to do more to assure their U.S. ally and partner neighbors that they will not wage massively destructive warfare against them. This latter requirement is key. If through deterrence, defense preparation, resiliency, and diplomatic resolution of tensions, the United States and its allies and partners can achieve mutual confidence with Russia, China, and North Korea that armed conflict will be eschewed and the potential for its escalation limited, then a no-first-use policy would become a recognized fact and would not need to be a declaratory policy.

ENDNOTES

1. Nuclear Posture Review Report, U.S. Department of Defense, April 2010, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/NPR/

2. Nuclear Posture Review, U.S. Department of Defense, February 2018, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF

3. Remarks by the Vice President on Nuclear Security, Washington, D.C., January 11, 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/12/remarks-vice-president-nuclear-security

4. Office of General Counsel, U.S. Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Law of War Manual,” December 2016, p. 86, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/DoD%20Law%20of%20War%20Manual%20-%20June%202015%20Updated%20Dec%202016.pdf?ver=2016-12-13-172036-190.

5. Steve Fetter and Jon Wolfsthal, “No First Use and Credible Deterrence,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2018): 102–114.

6. Paul McLeary, “New Hicks Memo Sets Acquisition, Force Posture 2022 Budget Priorities,” Breaking Defense, February 24, 2021.

7. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, I.C.J. Reports, July 8, 1996, para. 105(2)(E), https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/95/095-19960708-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf.

George Perkovich is the Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Chair and vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP). Pranay Vaddi is a fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at CEIP. This article is based on the authors’ January 2021 report, “Proportionate Deterrence: A Model Nuclear Posture Review.”

There is no perfect or nonproblematic nuclear weapons declaratory policy. One that sets the threshold for nuclear use too low invites international and perhaps domestic recriminations, along with arms racing and crisis instability. “These people are a menace,” competitors will say. “We must build up to stop them.” Nuclear disarmament advocates and non-nuclear-weapon states will say, “These people are a menace; we must disarm them.”

There is no perfect or nonproblematic nuclear weapons declaratory policy. One that sets the threshold for nuclear use too low invites international and perhaps domestic recriminations, along with arms racing and crisis instability. “These people are a menace,” competitors will say. “We must build up to stop them.” Nuclear disarmament advocates and non-nuclear-weapon states will say, “These people are a menace; we must disarm them.” Yet, this temptation to inflate the currency of nuclear weapons comes with risk. Bitter experience shows that possessing nuclear weapons does not deter all forms of aggression or coercion, nor does it guarantee winning wars. If nuclear deterrence did work against all forms of aggression and guarantee victory in war, many more states would want to acquire these weapons, which poses other risks. Overreliance on nuclear deterrence also can create a strategic and moral hazard of decreasing the resolve of politicians and polities to prevent conflicts at the outset and to acquire conventional and other defenses to deter or defeat less-than-existential threats.

Yet, this temptation to inflate the currency of nuclear weapons comes with risk. Bitter experience shows that possessing nuclear weapons does not deter all forms of aggression or coercion, nor does it guarantee winning wars. If nuclear deterrence did work against all forms of aggression and guarantee victory in war, many more states would want to acquire these weapons, which poses other risks. Overreliance on nuclear deterrence also can create a strategic and moral hazard of decreasing the resolve of politicians and polities to prevent conflicts at the outset and to acquire conventional and other defenses to deter or defeat less-than-existential threats. Ultimately, Russia and China, like the United States, pay more attention to capabilities than declared intentions. A no-first-use declaration would be relatively meaningless to Moscow and Beijing without reductions in the weapons that are most tied to such a policy. Yet, the political capital that a president would expend to push this declaration through the U.S. system and allied governments would leave little to overcome traditional resistance to alter the force posture. Opponents, including vocal members of Congress, would produce quotes from current and recently retired military leaders decrying the change and accusing the president of being weak on national security and the threats from Russia and China. To balance the perceived diminution of nuclear deterrence, the administration would face added pressure, including from Democratic members of Congress, to increase spending on nuclear modernization or at least not to pause or cut controversial programs under review.

Ultimately, Russia and China, like the United States, pay more attention to capabilities than declared intentions. A no-first-use declaration would be relatively meaningless to Moscow and Beijing without reductions in the weapons that are most tied to such a policy. Yet, the political capital that a president would expend to push this declaration through the U.S. system and allied governments would leave little to overcome traditional resistance to alter the force posture. Opponents, including vocal members of Congress, would produce quotes from current and recently retired military leaders decrying the change and accusing the president of being weak on national security and the threats from Russia and China. To balance the perceived diminution of nuclear deterrence, the administration would face added pressure, including from Democratic members of Congress, to increase spending on nuclear modernization or at least not to pause or cut controversial programs under review. The arguments from the expert academic and strategic nuclear policy community against homeland missile defense, which largely focus on the strategic impact of missile interceptors in stimulating countermoves, technical challenges, and high costs, have mostly ignored this feature of the politics surrounding the issue. Particularly in recent years, opponents of missile defense in Congress generally have failed to make key strategic arguments. This article outlines key gaps in congressional arguments against national missile defense aimed at defending the American public from a nuclear attack.

The arguments from the expert academic and strategic nuclear policy community against homeland missile defense, which largely focus on the strategic impact of missile interceptors in stimulating countermoves, technical challenges, and high costs, have mostly ignored this feature of the politics surrounding the issue. Particularly in recent years, opponents of missile defense in Congress generally have failed to make key strategic arguments. This article outlines key gaps in congressional arguments against national missile defense aimed at defending the American public from a nuclear attack. This testing has drawn its own critiques from the expert academic and nuclear policy community. For years, the testing of missile defense systems did not involve realistic scenarios such as countermeasures against intercept. Although the realism of testing has improved, critics note that the United States has never carried out a strategic missile defense test against multiple simulated targets, at night, or when the sun is in the interceptor’s field of view, which could make for a more challenging sensing environment.

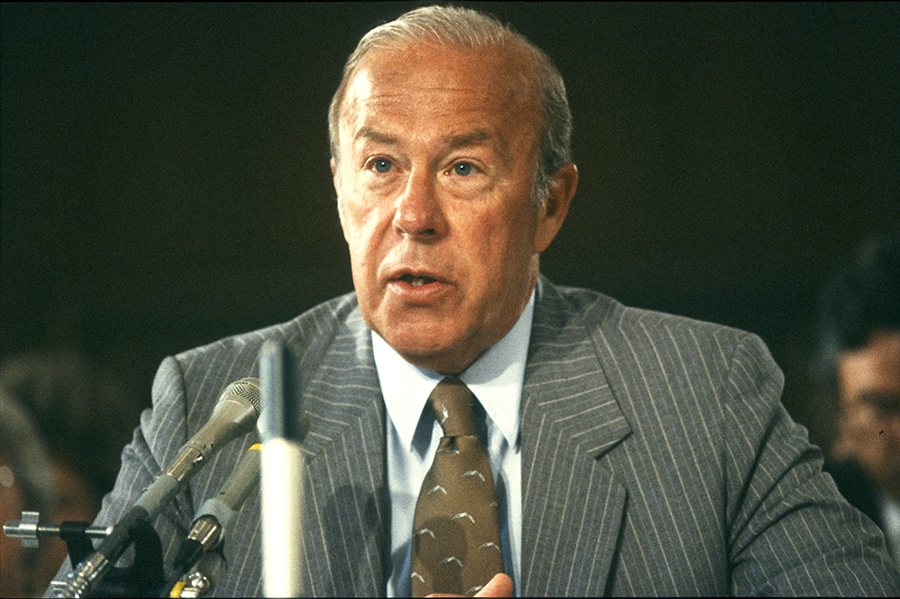

This testing has drawn its own critiques from the expert academic and nuclear policy community. For years, the testing of missile defense systems did not involve realistic scenarios such as countermeasures against intercept. Although the realism of testing has improved, critics note that the United States has never carried out a strategic missile defense test against multiple simulated targets, at night, or when the sun is in the interceptor’s field of view, which could make for a more challenging sensing environment. Shultz died on February 6 after an extraordinary life in service to his country, his causes, and his loved ones. He was a man of great moral clarity, uncommon skills, and common sense. Shultz succeeded in whatever ways he chose to apply his prodigious talents. His commitment to public service was inculcated at home by quietly purposeful parents and at Princeton University. After graduation, he joined the Marines to fight for the country in World War II.

Shultz died on February 6 after an extraordinary life in service to his country, his causes, and his loved ones. He was a man of great moral clarity, uncommon skills, and common sense. Shultz succeeded in whatever ways he chose to apply his prodigious talents. His commitment to public service was inculcated at home by quietly purposeful parents and at Princeton University. After graduation, he joined the Marines to fight for the country in World War II. James Timbie, who worked with many secretaries of state on arms control, found Shultz to be “a sophisticated man who navigated very tricky waters.” Timbie stresses that he was also an uncommonly good listener. If you made a persuasive case, Shultz would take it in and carefully consider the pros and cons. Shultz listened to Reagan. Something must have struck a chord—perhaps it was Reagan’s moral clarity on the nuclear issue—but Shultz was not someone who turned on a dime. His friend and guide on matters of the spirit, Episcopal Bishop William Swing, knew Shultz as someone who could change his mind. After doing so, he would become a tenacious advocate.

James Timbie, who worked with many secretaries of state on arms control, found Shultz to be “a sophisticated man who navigated very tricky waters.” Timbie stresses that he was also an uncommonly good listener. If you made a persuasive case, Shultz would take it in and carefully consider the pros and cons. Shultz listened to Reagan. Something must have struck a chord—perhaps it was Reagan’s moral clarity on the nuclear issue—but Shultz was not someone who turned on a dime. His friend and guide on matters of the spirit, Episcopal Bishop William Swing, knew Shultz as someone who could change his mind. After doing so, he would become a tenacious advocate. The U.S. State Department and the Russian Foreign Ministry issued separate statements Feb. 3 announcing that the formal exchange of documents on the extension had been completed. The treaty was set to expire Feb. 5.

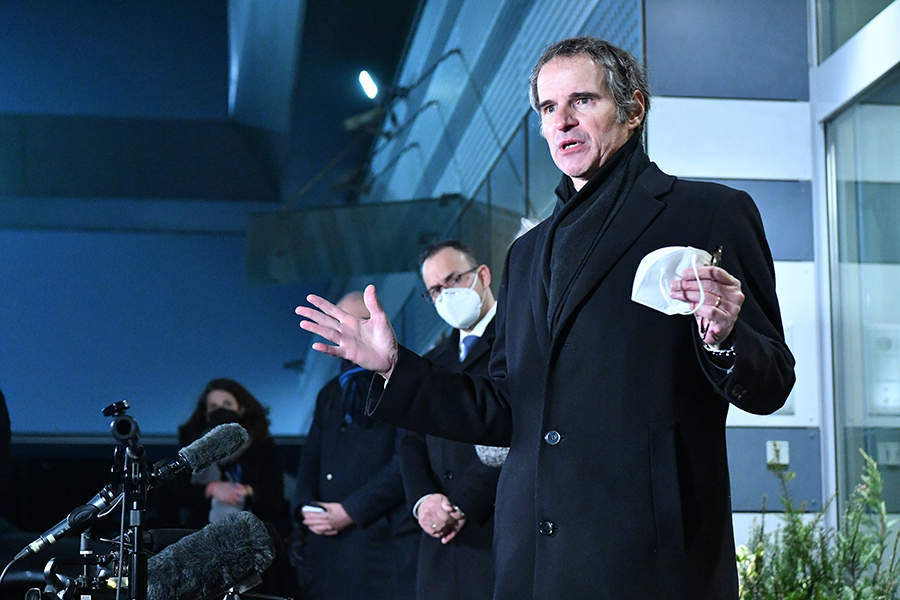

The U.S. State Department and the Russian Foreign Ministry issued separate statements Feb. 3 announcing that the formal exchange of documents on the extension had been completed. The treaty was set to expire Feb. 5. According to a joint statement issued by the IAEA and the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), the two parties reached a “temporary bilateral technical understanding” that will allow the agency to “continue with its necessary verification and monitoring activities” for three months.

According to a joint statement issued by the IAEA and the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), the two parties reached a “temporary bilateral technical understanding” that will allow the agency to “continue with its necessary verification and monitoring activities” for three months. Uranium metal production is prohibited by the 2015 nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), for 15 years. Iran’s most recent technical violation of the accord is significant due to the fact that Iranian scientists are not believed to have engaged in uranium metal work prior to the JCPOA. Technical knowledge gained through the process of producing uranium metal could be applied to nuclear weapons development and cannot be unlearned.

Uranium metal production is prohibited by the 2015 nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), for 15 years. Iran’s most recent technical violation of the accord is significant due to the fact that Iranian scientists are not believed to have engaged in uranium metal work prior to the JCPOA. Technical knowledge gained through the process of producing uranium metal could be applied to nuclear weapons development and cannot be unlearned. During his first major foreign policy address, delivered from the State Department on Feb. 4, Biden also pledged support for a ceasefire and revitalizing peace talks between warring factions in Yemen, including through the appointment a special envoy to the conflict. On Feb. 16, the State Department lifted the Jan. 19 designation of one of the major actors, the Houthis, as a foreign terrorist organization. The designation was one of the last acts by the Trump administration related to the conflict.

During his first major foreign policy address, delivered from the State Department on Feb. 4, Biden also pledged support for a ceasefire and revitalizing peace talks between warring factions in Yemen, including through the appointment a special envoy to the conflict. On Feb. 16, the State Department lifted the Jan. 19 designation of one of the major actors, the Houthis, as a foreign terrorist organization. The designation was one of the last acts by the Trump administration related to the conflict. The Biden administration, meanwhile, has begun a review of whether and, if so, how it would be possible to return the United States to the treaty after the Trump administration exited the multilateral agreement last year over objections from members of Congress and key European allies.

The Biden administration, meanwhile, has begun a review of whether and, if so, how it would be possible to return the United States to the treaty after the Trump administration exited the multilateral agreement last year over objections from members of Congress and key European allies. On Mar. 1, the commission is poised to deliver its final report to Congress and the White House. From the very start, this effort has been deemed an essential drive to ensure U.S. leadership in what is viewed as a competitive struggle with potential adversaries, presumably China and Russia, to weaponize advances in AI.

On Mar. 1, the commission is poised to deliver its final report to Congress and the White House. From the very start, this effort has been deemed an essential drive to ensure U.S. leadership in what is viewed as a competitive struggle with potential adversaries, presumably China and Russia, to weaponize advances in AI.