March 2022

By Marina Favaro and Elke Schwarz

Nearly 30 years ago, the fate of humankind hung in the balance when a Soviet Union early-warning system indicated that a series of U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) were headed toward Soviet soil. The alert came with a “high reliability” label. At the height of the Cold War, Soviet doctrine prescribed that a report of incoming U.S. missiles would be met with full nuclear retaliation—there would be no time for double checking, let alone for negotiations with the United States.

The officer on duty that day, Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, had a quick decision to make. Reporting the incoming strike flagged by the system would result in a nuclear strike by the Soviet forces; not reporting it could risk making an error that would prove devastating for the Soviet Union. After a moment of consideration, Petrov went with his gut feeling and concluded that the likelihood of a system error was too great to risk a full-scale nuclear war. Indeed, the system had misidentified sunlight reflected from clouds for missiles. The worst had been avoided.

The officer on duty that day, Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, had a quick decision to make. Reporting the incoming strike flagged by the system would result in a nuclear strike by the Soviet forces; not reporting it could risk making an error that would prove devastating for the Soviet Union. After a moment of consideration, Petrov went with his gut feeling and concluded that the likelihood of a system error was too great to risk a full-scale nuclear war. Indeed, the system had misidentified sunlight reflected from clouds for missiles. The worst had been avoided.

That incident, now a well-known chapter in nuclear weapons history, occurred in 1983, when the pace of weapons technology advancement was comparatively slow, when aspirations to accelerate decision-making through real-time computational technologies were not yet within reach, and when advances in military human enhancement were comparatively limited. The current military-operational context is very different.

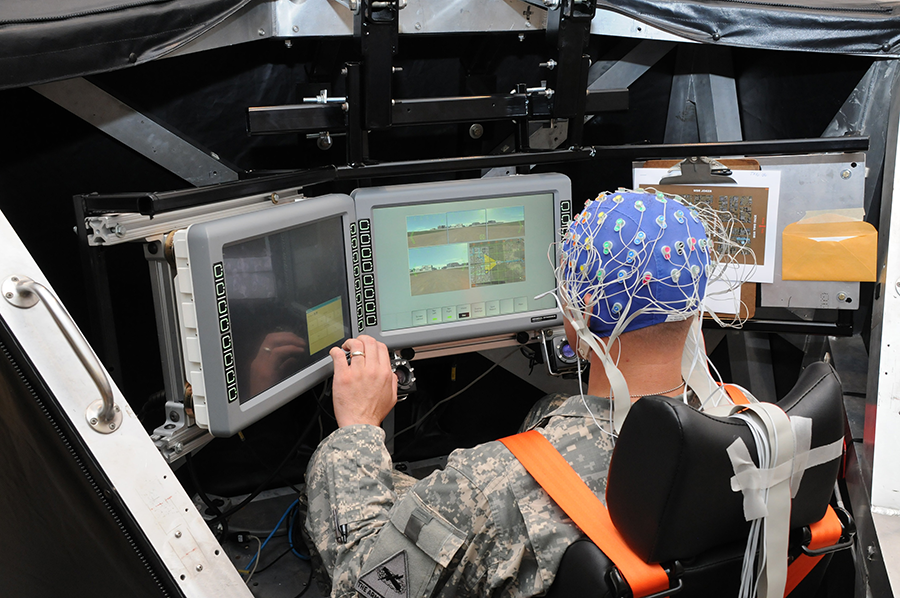

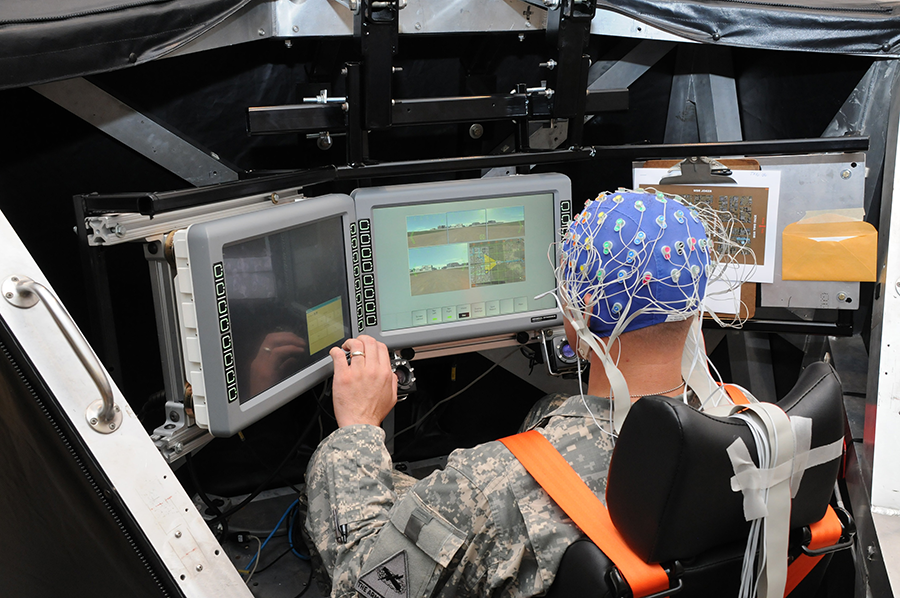

Today, renewed great-power competition is being intensified by technological advancements that allow for the real-time relay of information that requires decisions be made within seconds. Human beings are embedded much more intricately into the military technological systems logic, as operator and functional element, in the pursuit of speed and optimization. In order to function within a highly scientific, technologically sophisticated conflict environment, those involved in the action chain, including operators and fighters, are themselves in need of a tune-up.

Indeed, military human enhancement is one of the new frontiers in emerging weapons technology, as advanced militaries across the globe are planning to enhance and augment the capabilities of their war-fighting forces. This development is shifting the parameters of decision-making, including nuclear decision-making. What, for example, might have happened if Petrov had been more intricately woven into the computer system that reported the erroneous satellite signal, perhaps via an implantable neural interface to facilitate speedier human-machine communication for more efficient decision-making? Notwithstanding its operational and strategic importance, human augmentation is not typically discussed in nuclear policy. This oversight needs redress as ministries of defense begin to focus on human enhancement as the “missing part” of the human-machine teaming puzzle.1

Definition and History of Human Augmentation

Human augmentation is a vast field with many linkages to other areas of study. There is no commonly agreed definition, and it is known by many names, which are often used interchangeably. “Augmentation” usually refers to the transformation of capabilities to include a new or additional capability, but “enhancement” refers to the fortification of existing capabilities. Both concepts can be broadly defined as “the application of science and technologies to temporarily or permanently improve human performance.”2 As with all emerging technologies, human enhancement technologies exemplify aspects of continuity and change.

The development of physically and mentally resilient soldiers has a long history, involving techniques and technologies that work toward fortifying the human body and mind with the objective of extending capacities and limiting vulnerabilities in war. Such technological transformations begin with straightforward tools such as a soldier’s armor, the crossbow, the machine gun, the rocket launcher, and a range of natural and synthetic substances with pharmacological effects. Roman and Greek legionnaires strengthened their bodies with leather and bronze and their resolve with wine, beer, rum, and brandy. Opioids and amphetamines have long been used in battle to gain a greater edge in fighting.3 Pain relievers and other synthetic drugs are instrumental in alleviating pain and facilitating healing. Meanwhile, propaganda, systematic training, and enemy dehumanization are used to augment or suppress the war-fighter’s emotions. Human augmentation programs today extend much further into the development of the soldier as fighter, as well as the solider as operator, through various modes of scientific-technological inscriptions, shaping bodies toward greater operational efficiency and effectiveness.

As human and machine become increasingly entwined, the concept of the “super soldier,” where human tissue and technological circuitry fuse for maximum performance, is taking shape. In May 2021, the UK Ministry of Defence and the German Bundeswehr co-published a report that conceptualizes “the person as a platform” and heralds the “coming of the Biotech age.”4 Half a year earlier, China and France published reports indicating their readiness to augment military personnel physically, cognitively, psychologically, and pharmacologically.5,6 In the United States, the Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency has been investing in neurotechnology since the 1970s and today is expanding the frontiers of the field, with a focus on neural interface technology.7

Current trends in military human enhancement focus on external enhancements such as augmented reality, exoskeletons, wearables, and biosensors and internal augmentations through pharmacological supplements. Implantable chips for a medical or curative purpose are already on the horizon.8 Directly enhancing human capabilities, however, is only half of the equation. The other half is that human augmentation will become increasingly relevant to security and defense because it is the binding agent between humans and machines.9 Beyond these external and internal enhancements, there is considerable interest in developing technologies that facilitate smoother and more functional teaming between the human and computational systems through so-called neural interface technologies.

The importance of effective integration of humans and machines is widely acknowledged, but has been primarily viewed from a technocentric perspective. Many of the existing solutions are technology focused, such as “building trust into the system” by making artificial intelligence (AI) more transparent, explainable, and reliable. Although this is necessary for cultivating trust in human-machine teams, it does not account for the human element in the teaming equation. Proponents of human augmentation argue that it is the necessary adjustment for a world in which future wars will be won by those who can most effectively integrate the capabilities of personnel and machines at the appropriate time, place, and location.10

As militaries increasingly incorporate automated and autonomous processes into their operations, brain-interface technologies could serve as a crucial element in future human-machine teaming.11 Brain-interface technologies offer methods and systems for providing a direct communication pathway between an enhanced, or wired, brain and an external device.12 In other words, they enable the transfer of data between the human brain and the digital world via a neural implant. This has implications for all spheres of military operations. What might this mean for the future of nuclear decision-making?

Human Augmentation and Nuclear Stability

The United States is a good case study for understanding how human augmentation might intersect with nuclear decision-making, given that it is more transparent about its nuclear decision-making protocols than other states possessing nuclear weapons.

There is a clear sequence of events involved in the short period from considering a nuclear strike to the decision to launch.13 When the president decides that a launch is an option, they convene a brief conference of high-ranking advisers, including members of the military, such as the officer in charge of the war room. Whatever the president decides, the Pentagon must implement. For a strike decision, the next step is to authenticate the order, then the encoded order goes out via an encrypted message. Once the launch message has been received by the submarine and ICBM crews, the sealed authentication system codes are retrieved and compared with the transmitted codes in a further authentication step before launch. The missile launch then is prepared. If launched from a silo, it takes five ICBM crew members to turn their keys simultaneously for a successful launch. This entire process from decision to ICBM launch can be completed within five minutes, 15 minutes if the launch is executed from a submarine. This is already a quick decision process with very little room for mediation, deliberation, or error. With human augmentation, the timelines would be compressed even further.

To understand the relevance of human augmentation to nuclear decision-making, three scenarios, each positioned at different points in the decision-making process, are illustrative and reflect a military context in which nuclear weapons interact with a brain-computer interface. Such an interface could detect when certain areas of the brain are cognitively activated (e.g., by certain thoughts) and transmit this signal, thereby enabling brain-controlled action or communication. The scenarios focus on the incorporation of a brain-computer interface into nuclear decision-making because of their potential to accelerate communications. The ability of an interface to compress temporal timelines enables us to probe the boundaries of the question “What is the value of a few seconds?”

To understand the relevance of human augmentation to nuclear decision-making, three scenarios, each positioned at different points in the decision-making process, are illustrative and reflect a military context in which nuclear weapons interact with a brain-computer interface. Such an interface could detect when certain areas of the brain are cognitively activated (e.g., by certain thoughts) and transmit this signal, thereby enabling brain-controlled action or communication. The scenarios focus on the incorporation of a brain-computer interface into nuclear decision-making because of their potential to accelerate communications. The ability of an interface to compress temporal timelines enables us to probe the boundaries of the question “What is the value of a few seconds?”

The first scenario involves the advisory and decision chain. Assuming the above decision chain, the president, upon learning of a potential threat and considering the need to give a nuclear launch command, could shorten the deliberation time frame of their human advisers by transferring data directly to military participants via a brain-computer interface. In addition, the senior military commander could be plugged into an AI system that can compute many possible scenarios and give recommendations through the brain-computer interface in real time.

The upshot of human enhancement in this scenario might be that the military adviser has more data available through the interface, but critically, there is no guarantee of the quality or accuracy of this data. Moreover, with civilian and military advisers partaking in the advisory conference, there is a risk of the same algorithmic bias that is evident in human-machine teaming with AI systems. This refers to the tendency of humans to give uncritical priority to decisions that are ascertained with the help of technology, also called automation bias. This may make an advisory team superfluous and weaken the quality of advice in a critical situation. The mandate to act faster based on technologically derived advice could prevail and shorten the deescalation window.

In the second scenario, involving the executive chain, the launch crew is assumed to be partially or wholly networked through brain-computer interfaces. Perhaps the transmission of the launch codes takes place directly through computational networks, shortening the time between receiving the order, authenticating the codes, and executing the order. The submarine and ICBM crews executing the order by coordinated action are networked to facilitate the launch. In addition to the obvious vulnerabilities that any network inevitably produces, such as information and network security compromises, this would have the consequence of accelerating action. Any errors may be overlooked or not acted on in time. Particularly concerning is the possibility that a given action could rest on flawed initial inputs or skewed calculations, which would greatly increase the risk of unwarranted escalation.

Finally, there is the Petrov example, or the predecision phase. As suggested above, the decision chain does not really begin with the president’s decision to launch but with the input that the president receives from those in the military chain of command. If Petrov, the Russian duty officer whose job was to register apparent enemy missile launches, had been operating with a brain-computer interface in place and received the information transmitted directly to his brain and the brains of other military personnel, would there have been the impetus or indeed the opportunity to question the information from the system? Would he have had enough time to understand the context, draw on his experience, and make a considered judgment; or might he have felt compelled to uncritically execute the recommendations made by the system, which may well be indistinguishable in his mind to his own judgments?

In all three scenarios, the human is less able to exercise important human judgment at critical nuclear flashpoints. Algorithmic bias, increased system fog, lack of overall situational awareness, cognitive overload, and an accelerated action chain are consequences of intricate human-machine teaming through interfaces. This blurring of boundaries could obscure where machine input starts and human judgment ends. It could reduce the scope for cognitive input from the human and increase the extent to which algorithmic decisions prevail without serious oversight. Human experience and foresight based on noncomputational parameters are likely to be bracketed considerably. Is that wise in a nuclear context? As military operations prioritize speed and networked connectivity, slotting the human into a computer interface in the nuclear context may significantly exacerbate nuclear instability.14

Other Major Concerns

Regardless of its impact on nuclear stability, military human enhancement raises a myriad of ethical, legal, political, and other concerns that need to be explored. Among the questions that arise in this context, one involves consent, namely, can soldiers give free and informed consent to these enhancements, especially those that require a surgical procedure or invasive treatment, without pressure from their employer or peers? Will soldiers who consent to these interventions become part of an elite class of super soldiers, and what would be the impact of two classes of soldiers, enhanced and unenhanced, on morale? For how long would soldiers consent to these enhancements? Can an enhanced soldier ever go off duty or retire from service? In other words, when soldiers leave service, are they able to reverse these interventions? If not, what kinds of additional issues could this create for those who leave the service, who already encounter difficulties adjusting to a civilian environment?15 These consent issues are magnified in the many countries that maintain conscription.

Second, has the practice of military human enhancement already created an arms race, with states scrambling to out-enhance each other?16 Already locked in an ostensible arms race for dominance in military AI,17 the United States, China, and Russia, among other states with advanced militaries, are all keeping a close eye on who is enhancing their fighting forces and how.18 If human enhancement is the missing link in perfecting human-machine teaming, a race in this arena is perhaps inevitable. Oversights and flaws associated with arms racing then become a cause for concern, especially given that human integrity is on the line.

Second, has the practice of military human enhancement already created an arms race, with states scrambling to out-enhance each other?16 Already locked in an ostensible arms race for dominance in military AI,17 the United States, China, and Russia, among other states with advanced militaries, are all keeping a close eye on who is enhancing their fighting forces and how.18 If human enhancement is the missing link in perfecting human-machine teaming, a race in this arena is perhaps inevitable. Oversights and flaws associated with arms racing then become a cause for concern, especially given that human integrity is on the line.

Third, what kinds of information security concerns does human enhancement create? If service personnel use dual-use computer technologies in the same way as civilians use them, is it possible that this technology could create vulnerabilities and reveal sensitive data?19 Everything that is digitally connected can, in principle, be hacked. What kinds of vulnerabilities will be created by connection of the brain to a computer or by an increased number of networked devices, such as biosensors? How does the mere potential of cyberattacks on wearable or transdermal devices erode trust in the system? How can mass personal data collection and use be done without infringing on privacy?

Finally, who has this technology, and how do they use it? What kinds of interoperability concerns might military human enhancement create between allies? How might an asymmetry between “red” and “blue” forces using this technology impact nuclear stability? On a more philosophical note, if there is an accelerated action chain in a nuclear conflict, can such wars be won?

Averting Nuclear Risk

Notwithstanding the risks that embedding a brain-computer interface into nuclear decision-making could create, some types of enhancements could significantly benefit nuclear stability. It would be alarmist to focus exclusively on the risks created by human augmentation without also highlighting the potential opportunities. Indeed, brain-computer interfaces can provide new ways of accessing vast amounts of information and new ways of communication if human judgment is not sidelined in the process.

One significant opportunity created by military human enhancement relates to minimizing the risk of accidents. Nuclear weapons duty is known to be conducive to serious behavioral problems due to isolation, monotony, and confinement. During emergencies, sleep deprivation and heavy responsibilities may cause inaccuracy in judgment, hostility, or paranoia.20 In a prolonged nuclear alert, missile crews have reported visual hallucinations, balance disturbances, slowed movements, and lack of vigilance. The advantages of biosensors and bioinformatics to identify, predict, and treat such symptoms or at least give operators a break when needed could minimize the likelihood of nuclear war as a result of miscalculation, misunderstanding, or misperception. Indeed, evidence suggests that the world has been lucky, given the number of instances in which nuclear weapons could have been used inadvertently as a result of miscalculation or error.21 Future research should examine historical cases of nuclear near use and determine whether human augmentation could have minimized the likelihood of these disturbingly close calls. Meanwhile, bioinformatics could play a key role in identifying commanders and staff with the right cognitive and adaptive potential for command and control roles.22

There are also indications that biosensors could assist in the detection of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear agents embedded in smart clothing;23 better identify signs of nuclear activities,24 including weapons development; monitor and respond to radiation, including proposing treatment options in response to nuclear fallout;25 and prevent the illegal transportation and transfer of nuclear materials.26 This is not an exhaustive list; there are certainly other unforeseeable ways in which human augmentation will be relevant to the nuclear order, nuclear disarmament, and nuclear policy.

As is the case with all emerging technologies, there are risks and opportunities related to human augmentation and nuclear decision-making. On the one hand, human augmentation could minimize the risk of accidents and enable better human-machine teaming. On the other hand, there are profound legal, ethical, information security, and personnel-related questions that are overdue for rigorous examination. More research programs should consider how to mitigate the risks associated with human enhancement technologies, while remaining cognizant of their potential benefits. Ultimately, the question is, What is the value of a few additional seconds or minutes in the nuclear decision-making process, and are the trade-offs worthwhile?

Fortunately, the world is still some distance from a future of ubiquitous human augmentation, and the hype that suggests otherwise must be met with skepticism. Even so, human augmentation and nuclear decision-making have long been bedfellows; and the changing nature of war in the 21st century demands that all citizens, not just political and military leaders and technology experts, think deeply about what new risks and opportunities this intersection could unleash.

ENDNOTES

1. UK Ministry of Defence, “Human Augmentation—The Dawn of a New Paradigm,” May 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/986301/Human_Augmentation_SIP_access2.pdf.

2. Ibid.

3. Norman Ohler, Blitzed (New York: Penguin, 2017).

4. UK Ministry of Defence, “Human Augmentation.”

5. Elsa B. Kania and Wilson VornDick, “China’s Military Biotech Frontier: CRISPR, Military-Civil Fusion, and the New Revolution in Military Affairs,” China Brief, Vol. 19, No. 18 (October 8, 2019), https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Read-the-10-08-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF2.pdf.

6. Pierre Bourgois, “‘Yes to Iron Man, No to Spiderman!’ A New Framework for the Enhanced Soldier Brought by the Report From the Defense Ethics Committee in France,” IRSEM Strategic Brief, No. 18 (February 24, 2021), https://www.irsem.fr/media/5-publications/breves-strategiques-strategic-briefs/sb-18-bourgois.pdf.

7. U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), “DARPA and the Brain Initiative,” n.d., https://www.darpa.mil/program/our-research/darpa-and-the-brain-initiative (accessed February 13, 2022).

8. Emily Waltz, “How Do Neural Implants Work?” IEEE Spectrum, January 20, 2020, https://spectrum.ieee.org/what-is-neural-implant-neuromodulation-brain-implants-electroceuticals-neuralink-definition-examples.

9. NATO Science & Technology Organization, “Science & Technology Trends 2020–2040: Exploring the S&T Edge,” March 2020, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2020/4/pdf/190422-ST_Tech_Trends_Report_2020-2040.pdf.

10. UK Ministry of Defence, “Human Augmentation.”

11. Anika Binnendijk, Timothy Marler, and Elizabeth M. Bartels, “Brain-Computer Interfaces: U.S. Military Applications and Implications,” RAND Corp., RR-2996-RC, 2020, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2900/RR2996/RAND_RR2996.pdf.

12. Ibid.

13. Dave Merrill, Nafeesa Syeed, and Brittany Harris, “To Launch a Nuclear Strike, President Trump Would Take These Steps,” Bloomberg, January 20, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/graphics/2016-nuclear-weapon-launch/.

14. Olivier Schmitt, “Wartime Paradigms and the Future of Western Military Power,” International Affairs, Vol. 96, No. 2 (March 2020): 401–418, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa005.

15. Sarah Grand-Clement et al., “Evaluation of the Ex-Service Personnel in the Criminal Justice System Programme,” RAND Corp., RR-A624-1, 2020, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA600/RRA624-1/RAND_RRA624-1.pdf.

16. Yusef Paolo Rabiah, “From Bioweapons to Super Soldiers: How the UK Is Joining the Genomic Technology Arms Race,” The Conversation, April 29, 2021, https://theconversation.com/from-bioweapons-to-super-soldiers-how-the-uk-is-joining-the-genomic-technology-arms-race-159889.

17. Richard Walker, “Germany Warns: AI Arms Race Already Underway,” Deutsche Welle, June 7, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/artificial-intelligence-cyber-warfare-drones-future/a-57769444.

18. Thom Poole, “The Myth and Reality of the Super Soldier,” BBC News, February 8, 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-55905354.

19. Alex Hern, “Fitness Tracking App Strava Gives Away Location of Secret US Army Bases,” The Guardian, January 28, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/28/fitness-tracking-app-gives-away-location-of-secret-us-army-bases.

20. A.W. Black, “Psychiatric Illness in Military Aircrew,” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 54, No. 7 (July 1983): 595-598.

21. Patricia Lewis, Benoît Pelopidas, and Heather Williams, “Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy,” Chatham House, April 28, 2014, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2014/04/too-close-comfort-cases-near-nuclear-use-and-options-policy.

22. UK Ministry of Defence, “Human Augmentation.”

23. Richard Ozanich, “Chem/Bio Wearable Sensors: Current and Future Direction,” Pure and Applied Chemistry, Vol. 90, No. 10 (June 12, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2018-0105.

24. “New Biosensor Could Help Search for Nuclear Activity,” CBRNE Central, February 22, 2017, https://cbrnecentral.com/new-biosensor-could-help-search-for-nuclear-activity/10601/.

25. M. Gray et al., “Implantable Biosensors and Their Contribution to the Future of Precision Medicine,” The Veterinary Journal, Vol. 239 (September 2018), pp. 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.07.011.

26. Thamir A.A. Hassan, “Development of Nanosensors in Nuclear Technology,” AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 1799, No. 1 (January 6, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4972925.

Marina Favaro is a research fellow at the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg, focusing on the impact of emerging technologies on international stability and human security. Elke Schwarz is a senior lecturer in political theory at Queen Mary University of London, focusing on the political and ethical implications of new technologies.

There are many grievances fueling Putin’s latest and most brazen attempt to reset the post-Cold War European security order through military force. Some are real, such as the effect of NATO’s expansion on the military balance in Europe, and some are imagined. No rationale, however, justifies a violent attack by Russia on one of its neighbors.

There are many grievances fueling Putin’s latest and most brazen attempt to reset the post-Cold War European security order through military force. Some are real, such as the effect of NATO’s expansion on the military balance in Europe, and some are imagined. No rationale, however, justifies a violent attack by Russia on one of its neighbors.

ACT: What do you see as the core of the Russian-Ukrainian crisis? What led Russia to demand security guarantees?

ACT: What do you see as the core of the Russian-Ukrainian crisis? What led Russia to demand security guarantees? GOTTEMOELLER: There is a major economic aspect of this, and that starts at the crisis in 2014 over Ukraine’s association agreement with the European Union. It had nothing to do with NATO. Ukrainians are heading to Europe in terms of its culture, its democratic practices, so it is also about Ukraine eventually joining the EU. For me, it’s a bit artificial the way Putin has created NATO as the enemy because NATO all along, and up to the invasion of Ukraine in 2014, was trying to promulgate a partnership with Russia based on the Rome Declaration of 2002 that Putin himself signed and included a wide range of pragmatic projects. They got increasingly difficult to implement in the years running up to 2014. But there were still some significant practical projects going on, like the European Airspace Initiative, right up to the invasion of Crimea.

GOTTEMOELLER: There is a major economic aspect of this, and that starts at the crisis in 2014 over Ukraine’s association agreement with the European Union. It had nothing to do with NATO. Ukrainians are heading to Europe in terms of its culture, its democratic practices, so it is also about Ukraine eventually joining the EU. For me, it’s a bit artificial the way Putin has created NATO as the enemy because NATO all along, and up to the invasion of Ukraine in 2014, was trying to promulgate a partnership with Russia based on the Rome Declaration of 2002 that Putin himself signed and included a wide range of pragmatic projects. They got increasingly difficult to implement in the years running up to 2014. But there were still some significant practical projects going on, like the European Airspace Initiative, right up to the invasion of Crimea. GOTTEMOELLER: I don’t disagree, but who are the Russians in this case? I think there are different views out there. There are Russians, [Andre] Kortunov [director-general of the Russian International Affairs Council], some retired military and KGB senior officers who are saying, “Is it really such a good idea to be heading in this direction of a war, invasion of Ukraine?” They are also saying, “Do we really want to abandon our Western-facing objectives and throw ourselves into the arms of China, is that a good idea?” The Russians aren’t monolithic on this. There always has been a debate of the Westernizers versus the Slavophiles. In this case, the Westernizers are those who still see the necessity of links to Europe for economic, cultural, [and] traditional reasons and because people like to send their kids to school in Europe versus those who say to heck with Europe, to heck with the West, we’re throwing ourselves into the arms of the Chinese.

GOTTEMOELLER: I don’t disagree, but who are the Russians in this case? I think there are different views out there. There are Russians, [Andre] Kortunov [director-general of the Russian International Affairs Council], some retired military and KGB senior officers who are saying, “Is it really such a good idea to be heading in this direction of a war, invasion of Ukraine?” They are also saying, “Do we really want to abandon our Western-facing objectives and throw ourselves into the arms of China, is that a good idea?” The Russians aren’t monolithic on this. There always has been a debate of the Westernizers versus the Slavophiles. In this case, the Westernizers are those who still see the necessity of links to Europe for economic, cultural, [and] traditional reasons and because people like to send their kids to school in Europe versus those who say to heck with Europe, to heck with the West, we’re throwing ourselves into the arms of the Chinese. ACT: What do you think is Putin’s goal? His foreign minister has called for “radical changes” in European security, among the litany of Russian demands.

ACT: What do you think is Putin’s goal? His foreign minister has called for “radical changes” in European security, among the litany of Russian demands. In the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997, NATO pledged it would not deploy “substantial permanent combat forces” in new member states. We adhere to that up to this point, but we may be able to define that with greater clarity. This would require reciprocity on the Russian part, which means they would have to undertake not to deploy their forces within a certain distance of the border, which means they will put limitations on their ability to move their own forces and staff on Russian territory. The Kremlin standpoint is that Russia has every sovereign right to deploy its forces anywhere it wants to on its sovereign territory and that shouldn’t be a problem for any other country [because] it’s not threatening. That said, if you’re planning on invading a country, you generally concentrate your forces along the border, right? So any concentration of forces along the border does raise legitimate concerns in neighboring countries as to what your intentions actually are. Can we negotiate something like that? I think the answer is yes, but it’s going to be difficult because it will require concessions on both sides. Reciprocity is something the United States is focused on. We believe Russia violated the INF [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces] Treaty. That’s the reason we withdrew or at least one of the reasons we withdrew. Russia had its own grievances about our missile defense sites in Poland and Romania.

In the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997, NATO pledged it would not deploy “substantial permanent combat forces” in new member states. We adhere to that up to this point, but we may be able to define that with greater clarity. This would require reciprocity on the Russian part, which means they would have to undertake not to deploy their forces within a certain distance of the border, which means they will put limitations on their ability to move their own forces and staff on Russian territory. The Kremlin standpoint is that Russia has every sovereign right to deploy its forces anywhere it wants to on its sovereign territory and that shouldn’t be a problem for any other country [because] it’s not threatening. That said, if you’re planning on invading a country, you generally concentrate your forces along the border, right? So any concentration of forces along the border does raise legitimate concerns in neighboring countries as to what your intentions actually are. Can we negotiate something like that? I think the answer is yes, but it’s going to be difficult because it will require concessions on both sides. Reciprocity is something the United States is focused on. We believe Russia violated the INF [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces] Treaty. That’s the reason we withdrew or at least one of the reasons we withdrew. Russia had its own grievances about our missile defense sites in Poland and Romania. It’s not a good Russian response because it is very hard-line. I can see points of overlap. Everybody at this point is okay with a European intermediate-range nuclear forces deal, even if we might have questions about its military usefulness, since the United States isn’t planning to do this anyway. I think the mutual inspections, exercise limits, and things like that, you can do these things. One big disconnect is the Russians want the limits where it’s Russian, and perhaps Belorussian, territory up against NATO territory. When it comes to Ukraine, the Russians want the ability to build up forces all around Ukraine, put a bunch of ships in the Black Sea with missiles on them, and threaten Ukraine. There is no new European security architecture deal, I don’t think, that doesn’t also take into account the security of countries like Ukraine one way or another. If the Russians really do push this “it’s a package, not a menu” story, I mean good luck with negotiating. You can’t negotiate one big package like this quickly.

It’s not a good Russian response because it is very hard-line. I can see points of overlap. Everybody at this point is okay with a European intermediate-range nuclear forces deal, even if we might have questions about its military usefulness, since the United States isn’t planning to do this anyway. I think the mutual inspections, exercise limits, and things like that, you can do these things. One big disconnect is the Russians want the limits where it’s Russian, and perhaps Belorussian, territory up against NATO territory. When it comes to Ukraine, the Russians want the ability to build up forces all around Ukraine, put a bunch of ships in the Black Sea with missiles on them, and threaten Ukraine. There is no new European security architecture deal, I don’t think, that doesn’t also take into account the security of countries like Ukraine one way or another. If the Russians really do push this “it’s a package, not a menu” story, I mean good luck with negotiating. You can’t negotiate one big package like this quickly. While it’s important to have this type of structure, we also need a genuinely confidential back channel where we can discuss what are very sensitive issues. Much of the dialogue over the past several months has been conducted in public. To a great extent, the Russians are to blame for that by publishing those treaties 24 to 48 hours after they had presented them to the United States. It was clear our response was going to be leaked at some point. But these are such sensitive issues, you can’t negotiate them seriously in the public glare because resolution will require backing away from stated positions. That’s very difficult to do given the political context in the United States. It’s also difficult to do on the Russian side. So if you’re really serious, you have to have a platform that is protected from the public glare, where serious people can get together and discuss very sensitive issues that will require difficult trade-offs. You have to do this in confidence and then present the total package to the public for debate. Any element of a compromise solution can be debated to death. When you see the whole package and how pieces fit together, you have a different assessment.

While it’s important to have this type of structure, we also need a genuinely confidential back channel where we can discuss what are very sensitive issues. Much of the dialogue over the past several months has been conducted in public. To a great extent, the Russians are to blame for that by publishing those treaties 24 to 48 hours after they had presented them to the United States. It was clear our response was going to be leaked at some point. But these are such sensitive issues, you can’t negotiate them seriously in the public glare because resolution will require backing away from stated positions. That’s very difficult to do given the political context in the United States. It’s also difficult to do on the Russian side. So if you’re really serious, you have to have a platform that is protected from the public glare, where serious people can get together and discuss very sensitive issues that will require difficult trade-offs. You have to do this in confidence and then present the total package to the public for debate. Any element of a compromise solution can be debated to death. When you see the whole package and how pieces fit together, you have a different assessment. Russian military leaders and analysts argue, however, that their counterspace weapons provide a means to restore strategic stability. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu characterized the test as a routine operation of a “cutting-edge future weapon system” to strengthen Russia’s deterrent and defense against U.S. attempts to attain “comprehensive military advantage” in space.

Russian military leaders and analysts argue, however, that their counterspace weapons provide a means to restore strategic stability. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu characterized the test as a routine operation of a “cutting-edge future weapon system” to strengthen Russia’s deterrent and defense against U.S. attempts to attain “comprehensive military advantage” in space. Yet, these fears permeate the Russian debate on the aerospace capabilities of U.S. and NATO forces. Russian military exercises are now designed to “repel a massive” aerospace strike by hypersonic weapons, short- and medium-range cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles with highly mobile anti-air and anti-space units.

Yet, these fears permeate the Russian debate on the aerospace capabilities of U.S. and NATO forces. Russian military exercises are now designed to “repel a massive” aerospace strike by hypersonic weapons, short- and medium-range cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles with highly mobile anti-air and anti-space units. These Russian motivations pose profound challenges to pursuing lasting space arms control measures. Several proposed nonbinding behavioral norms may stall the testing of ASAT weapons for the near term. For instance, U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks recently argued for a global ban on ASAT tests that create debris.

These Russian motivations pose profound challenges to pursuing lasting space arms control measures. Several proposed nonbinding behavioral norms may stall the testing of ASAT weapons for the near term. For instance, U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks recently argued for a global ban on ASAT tests that create debris. The officer on duty that day, Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, had a quick decision to make. Reporting the incoming strike flagged by the system would result in a nuclear strike by the Soviet forces; not reporting it could risk making an error that would prove devastating for the Soviet Union. After a moment of consideration, Petrov went with his gut feeling and concluded that the likelihood of a system error was too great to risk a full-scale nuclear war. Indeed, the system had misidentified sunlight reflected from clouds for missiles. The worst had been avoided.

The officer on duty that day, Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, had a quick decision to make. Reporting the incoming strike flagged by the system would result in a nuclear strike by the Soviet forces; not reporting it could risk making an error that would prove devastating for the Soviet Union. After a moment of consideration, Petrov went with his gut feeling and concluded that the likelihood of a system error was too great to risk a full-scale nuclear war. Indeed, the system had misidentified sunlight reflected from clouds for missiles. The worst had been avoided. To understand the relevance of human augmentation to nuclear decision-making, three scenarios, each positioned at different points in the decision-making process, are illustrative and reflect a military context in which nuclear weapons interact with a brain-computer interface. Such an interface could detect when certain areas of the brain are cognitively activated (e.g., by certain thoughts) and transmit this signal, thereby enabling brain-controlled action or communication. The scenarios focus on the incorporation of a brain-computer interface into nuclear decision-making because of their potential to accelerate communications. The ability of an interface to compress temporal timelines enables us to probe the boundaries of the question “What is the value of a few seconds?”

To understand the relevance of human augmentation to nuclear decision-making, three scenarios, each positioned at different points in the decision-making process, are illustrative and reflect a military context in which nuclear weapons interact with a brain-computer interface. Such an interface could detect when certain areas of the brain are cognitively activated (e.g., by certain thoughts) and transmit this signal, thereby enabling brain-controlled action or communication. The scenarios focus on the incorporation of a brain-computer interface into nuclear decision-making because of their potential to accelerate communications. The ability of an interface to compress temporal timelines enables us to probe the boundaries of the question “What is the value of a few seconds?” Second, has the practice of military human enhancement already created an arms race, with states scrambling to out-enhance each other?

Second, has the practice of military human enhancement already created an arms race, with states scrambling to out-enhance each other? “Western countries aren’t only taking unfriendly economic actions against our country, but leaders of major NATO countries are making aggressive statements about our country,” Putin said on Feb. 27 during a meeting with defense officials. “So, I order to move Russia’s deterrence forces to a special regime of combat duty.”

“Western countries aren’t only taking unfriendly economic actions against our country, but leaders of major NATO countries are making aggressive statements about our country,” Putin said on Feb. 27 during a meeting with defense officials. “So, I order to move Russia’s deterrence forces to a special regime of combat duty.” The negotiators have produced a 20-page document with appendixes on sanctions, nuclear commitments, and implementation of the restored agreement, including sequencing and verification, according to an unnamed Iranian source in Tehran. That source, quoted by the website Amwaj.media on Feb. 15, said the document reflects “the whole deal,” but is still under negotiation.

The negotiators have produced a 20-page document with appendixes on sanctions, nuclear commitments, and implementation of the restored agreement, including sequencing and verification, according to an unnamed Iranian source in Tehran. That source, quoted by the website Amwaj.media on Feb. 15, said the document reflects “the whole deal,” but is still under negotiation.

During the Feb. 3 meeting, Austin “noted the need for persistent dialogue in order to meet the department’s current and future capabilities requirements for defensive and offensive capabilities,” according to a Pentagon statement released afterward.

During the Feb. 3 meeting, Austin “noted the need for persistent dialogue in order to meet the department’s current and future capabilities requirements for defensive and offensive capabilities,” according to a Pentagon statement released afterward. Established in 2014, the mission has a mandate to determine whether chemical weapons or toxic chemicals have been used as weapons in Syria. It is not permitted to identify who is responsible for the incidents.

Established in 2014, the mission has a mandate to determine whether chemical weapons or toxic chemicals have been used as weapons in Syria. It is not permitted to identify who is responsible for the incidents.