March 2023

By Ray Acheson

Nuclear weapons are gendered. They have gendered impacts; their existence is predicated and perpetuated in part due to gendered norms about power, violence, and security; and their abolition is challenged by the stark lack of gender diversity in discussions and negotiations related to nuclear policy.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) has done a lot to address these issues in recent years, but other nuclear governance infrastructure, such as the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), has failed to do so. As a result, much more work is needed to advance intersectional approaches to nuclear weapons, an imperative for achieving nuclear abolition.

Gender and Disarmament

Broadly speaking, gender considerations feature in disarmament in three ways: the harm from specific weapons systems, the discourse within disarmament discussions, and the diversity among disarmament and arms control policymakers.

The latter topic has received the most attention within recent disarmament forums, including those related to nuclear weapons. There is a stark disparity in the level (seniority or rank) and the number of men as compared to women in disarmament, nonproliferation, and arms control discussions, negotiations, and processes. Moreover, most discourse and action related to this subject have centered on a binary notion of gender and thus neglected the intersectionality of identities and oppressions that lead to the marginalization and exclusion of certain people.

The latter topic has received the most attention within recent disarmament forums, including those related to nuclear weapons. There is a stark disparity in the level (seniority or rank) and the number of men as compared to women in disarmament, nonproliferation, and arms control discussions, negotiations, and processes. Moreover, most discourse and action related to this subject have centered on a binary notion of gender and thus neglected the intersectionality of identities and oppressions that lead to the marginalization and exclusion of certain people.

Feminist conceptions of intersectionality recognize that, although important, increasing the number of women is insufficient to challenge gender norms or diversify perspectives on weapons and militarism.1 Real diversity is not just about adding bodies to meeting rooms but also about creating space for nonhegemonic ideas, imaginations, and perspectives to inspire concrete changes in policy and practice. It is not useful to treat women as a monolithic group. Disarmament work needs people of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, races, classes, abilities, backgrounds, and experiences.

Diversity is not just for its own sake. It is essential for challenging socially constructed norms about identity that impact the approach of diplomats, activists, and academics toward weapons and militarism. Gender norms, for example, perpetuate a binary social construction of men who are violent and powerful and women who are vulnerable and need to be protected. The term “militarized masculinities” has been used by feminists and LGBTQ+ scholars and activists to describe the normative association of cisgendered, heterosexual masculinity with militarized violence. For instance, the framing of war and violence as “strong” and “masculine” is often coupled with a framing of peace and nonviolence as “weak” and “feminine.” In this context, weapons are typically seen as important for security, power, and control while disarmament is treated as something that makes countries weaker or more vulnerable.2

Nuclear weapons are a linchpin of militarized masculinities, signifying the ultimate form of strength and power. In this context, those who amplify the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and call for their prohibition often are accused of being “emotional” and “irrational,” which are typical gendered responses meant to feminize and thus ridicule.3 This gendered framing is extremely problematic with regard to accepting disarmament as a credible approach to security. The persistence of norms around what is considered rational and serious is further compounded by the lack of diversity. People with feminist, queer, and other nondominant perspectives can help challenge ideas that are treated as immutable truths and can articulate alternative conceptions of strength and security.

Diversity among participants and perspectives in disarmament diplomacy and decision-making also impacts consideration of how weapons cause harm and to whom they cause harm. Men tend to comprise most of the direct victims of armed violence and armed conflict. Sometimes, they are targeted for being men, which constitutes gender-based violence;4 but women, girls, and nonbinary and LGBTQ+ people often suffer harm that is disproportionate to the number of those directly involved in conflict or violence. Although less likely to wield weapons, women are still harmed by weapons. They are more likely to be targeted for acts of gender-based violence and may face social and political inequalities and pressures, including in accessing survivor assistance or participating in peace-building or postconflict reconstruction.5

Some weapons harm disproportionately or differentially based on sex. The ionizing radiation from nuclear weapons, for example, causes increased risk of cancers in cisgendered women and girls, affecting reproduction and maternal health.6 Social norms in certain societies also may lead women to suffer increased exposure to such radiation7 and subsequent ostracization.8

Weapons development, testing, and use also have racialized impacts. For example, the nuclear-armed states primarily have carried out nuclear weapons testing on the lands, water, and bodies of indigenous people. Settler states and colonial governments have mined uranium for nuclear weapons primarily on indigenous lands. Nuclear weapons development and radioactive waste storage are situated largely within or near poor communities, especially communities of color. Thus, diversity in participation and perspectives is not just about sex or gender. It also is essential for overcoming white supremacy, racism, and other forms of bias and discrimination in nuclear disarmament policy and practice.

Gender and the TPNW

All of these issues can and should be considered in the context of gender and disarmament. Some intergovernmental forums have started addressing the marginalization of women and the disproportionate gendered harm caused by weapons, but the nuclear space has largely ignored these concerns. So far, governments have not considered gendered norms such as militarized masculinities to any meaningful degree. Although activists and scholars increasingly are raising feminist, queer, and anti-racist perspectives on everything from small arms to nuclear bombs, government policymakers and disarmament diplomats largely have avoided such discussions in favor of an exclusive focus on women’s participation.

After decades of interventions by civil society, however, this approach is slowly starting to change. In addition to banning nuclear weapons, the TPNW, adopted at the United Nations in July 2017, recognizes the disproportionate impact of ionizing radiation on women and girls and calls for women’s increased participation in nuclear disarmament. At the first meeting of TPNW states-parties last June, participants adopted an action plan that commits them to implement the treaty’s gender provisions.9

This includes engaging relevant stakeholders, including international organizations, civil society, affected communities, indigenous peoples, and youth, at all stages of the victim assistance and environmental remediation process; providing victim assistance that is age and gender sensitive; developing guidelines for voluntary reporting on national measures related to victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation; integrating gender considerations as the treaty is implemented; and considering the different needs of people in affected communities and Indigenous people.

This includes engaging relevant stakeholders, including international organizations, civil society, affected communities, indigenous peoples, and youth, at all stages of the victim assistance and environmental remediation process; providing victim assistance that is age and gender sensitive; developing guidelines for voluntary reporting on national measures related to victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation; integrating gender considerations as the treaty is implemented; and considering the different needs of people in affected communities and Indigenous people.

The action plan mandated the establishment of a scientific advisory group comprised of a “geographically diverse and gender balanced network of experts” to support TPNW implementation. It also called for specific actions to operationalize the treaty’s gender provisions by emphasizing the gender-responsive nature of the treaty; taking gender considerations into account across all TPNW-related national policies, programs, and projects; and establishing a “gender focal point” to work during the intersessional period on guidelines for ensuring age- and gender-sensitive victim assistance and for integrating gender perspectives in international cooperation and assistance.

A diplomat from Chile’s UN mission has been appointed to the gender focal point position. A progress report is due at the second meeting of states-parties, to take place November 27–December 1 in New York under the presidency of Mexico.

The declaration approved at the states-parties’ meeting also reiterated a commitment to “work inclusively with affected communities” and emphasized “the innovative gender provisions of the treaty and…the importance of the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men in nuclear disarmament diplomacy.”10 Taken together, the declaration and action plan contain the most inclusive language of any outcome approved by a multilateral disarmament forum or treaty body to date.

The commitment to inclusivity was reflected further in the open consultation process organized by Austria, the meeting host, and in the meeting itself. Governmental representation from states-parties and signatories around the globe, especially from the Pacific region, Latin America and the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and Africa, was strong, while survivors, affected communities, and civil society groups from the global South participated more meaningfully and in greater numbers than in meetings of other nuclear treaty bodies. Even so, participation, especially among activists and academics, was still dominated by the global North and thus disproportionate to the treaty’s membership.

Other weaknesses also persist. The TPNW declaration and action plan reinforce a gender binary. They do not recognize other gender identities or gender nonconforming people, nor do they adequately advance an intersectional approach to disarmament beyond affected communities. These documents also do not comprehensively reflect or explicitly seek to address all harms generated by nuclear weapons.

As Diné activist Janine Yazzie, who is coordinating the protocols of the Nuclear Truth Project, said during a TPNW side event,

The catastrophic impacts of nuclear-related activities do not start nor end with the detonation of a bomb, nor does the mass murder end with the aftermath of the impacts of the blast. No, the mass murder from these industries, and those responsible for creating, investing and protecting them, continues as long as the devastation to the health of our peoples and our environment continues. As long as our waters are undrinkable, our soil is contaminated, and our babies are being born with uranium in their bodies.11

Similarly, in a letter to the Australian prime minister and parliament, members of the Yankunytjatjara, Kokotha, Adnyamathanha, Dieri, and Kuyani peoples and civil society groups in Australia noted that, “[f]ar from being a historical event, we are clear that the [nuclear] tests themselves were not the only damage. The waste left behind and the on-going complications and fears from fallout and contamination, and the mental scares, are still strongly felt in Aboriginal communities across the regions where testing took place.”12

The TPNW aims to stop nuclear threats, nuclear arms races, and nuclear weapons. It also aims at nuclear abolition, not just at arms control or disarmament. This means it aspires to justice, not just to dismantle bombs but to build a world that is safer for all in solidarity with all. In this sense, the TPNW is well suited to address these long-ignored harms and legacies. Although states-parties have more work to do to live up to this potential, the TPNW is still light-years ahead of other nuclear weapons-related treaties.

Gender and the NPT

In contrast, the other key nuclear governance treaty—the NPT—does not reference gender, affected communities, or indigenous populations, and neither do subsequent outcome documents and action plans adopted throughout the treaty’s more than 50-year history. It was only during the most recent NPT review cycle (2017–2022) that states-parties began incorporating any kind of gender perspective, primarily through calls for improving women’s participation and, less frequently, in relation to the gendered impacts of nuclear weapons use and testing.

In 2017, Ireland and Sweden presented research showing that women’s participation rate in NPT meetings is lower than in other multilateral forums. In 2019, both governments hosted side events at the NPT preparatory committee meeting related to gender and nuclear weapons. Ireland submitted working papers in 2017, 2018, and 2019 related to gender,13 and governments affiliated with the Gender Champions Initiative tabled working papers on women’s participation together with the UN Institute for Disarmament Research in 2019 and 2022.14 These papers do not sufficiently incorporate a gender analysis of nuclear weapons discourse or norms, nor sufficiently draw on the knowledge of marginalized people other than “women” in a monolithic sense.

In 2017, Ireland and Sweden presented research showing that women’s participation rate in NPT meetings is lower than in other multilateral forums. In 2019, both governments hosted side events at the NPT preparatory committee meeting related to gender and nuclear weapons. Ireland submitted working papers in 2017, 2018, and 2019 related to gender,13 and governments affiliated with the Gender Champions Initiative tabled working papers on women’s participation together with the UN Institute for Disarmament Research in 2019 and 2022.14 These papers do not sufficiently incorporate a gender analysis of nuclear weapons discourse or norms, nor sufficiently draw on the knowledge of marginalized people other than “women” in a monolithic sense.

Nevertheless, these working papers introduced the topic of gender and disarmament into the NPT context, which was then reflected in the official record. In 2017, the NPT preparatory committee chair included in his factual summary a recommendation for increasing women’s participation, noting that states-parties “emphasized the importance of promoting the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men in the process of nuclear nonproliferation, nuclear disarmament and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.”15 The summary said states-parties “were encouraged, in accordance with their commitments under United Nations Security Council resolution 1325, actively to support participation of female delegates in their own NPT delegations and through support for sponsorship programs.” It acknowledged the gendered impacts of radiation and called for this to be factored into discussions.

In 2018, the chair’s summary similarly noted that states-parties “endorsed the fundamental importance of promoting the equal, full and effective participation and leadership of both women and men in nuclear nonproliferation, nuclear disarmament and the peaceful use of nuclear energy.” They “welcomed the increased participation of women during the session and highlighted the importance of fulfilling commitments under Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000), to support actively the participation of female delegates in their own delegations, including through sponsorship programs.”16

The 2019 chair’s summary endorsed similar language on the “full and effective participation” of women and men and also encouraged states-parties, in accordance with Security Council Resolution 1325, “to actively support gender diversity in their NPT delegations and through support for sponsorship programs.” Finally, it recognized “the disproportionate impact of ionizing radiation on women and girls.”17

Despite the limited nature of these nonbinding reflections and recommendations, some states-parties pushed further at the 10th NPT Review Conference last August. Sixty-seven states-parties signed a joint statement on gender, diversity, and inclusion that recognized that “the intersections of race, gender, economic status, geography, nationality, and other factors must be taken into account as risk-multiplying factors” in relation to nuclear weapons. They noted that nuclear weapons have different effects on different demographics and recommended ways to address the impacts of nuclear weapons and diversify participation in disarmament and nonproliferation work.

Although the statement still largely focuses on increasing women’s participation in a binary and nonintersectional way, it recognizes that, “for women and other underrepresented groups, there must not only be a seat at the table, but also real opportunities to shape conversations, policies, and outcomes.”18

During negotiations on the review conference draft outcome document, a handful of delegations called for a reference to “all genders” in relation to participation, rather than the men-women binary. In urging a more intersectional approach, the Costa Rican delegation suggested language to encourage other metrics of diversity.19 Some governments opposed any reference to gender perspectives or diversity, while others accepted language on women’s participation but opposed the term “all genders.”

In the end, the draft outcome document, which was not adopted for other political reasons, contained eight paragraphs that called for an enhancement of women’s participation in the work of the NPT.20 Although this was a binary rather than intersectional approach, the text was an improvement over past NPT documents, which contain zero references to these issues. In another first for an NPT document, the final draft included a reference to providing assistance to people and communities affected by nuclear weapons use and testing. That was a clear testament to the long, difficult work of TPNW states-parties, civil society groups, and affected communities in raising these issues.

Intersectional Feminism and Nuclear Abolition

Whether in the context of the TPNW or the NPT, the commitment to advancing gender perspectives and diversity in disarmament is still largely words on paper. As has been seen time and again in previous initiatives, women’s participation in disarmament meetings and processes does not necessarily lead to meaningful change. Bodies or identities in themselves do not change policy. Alternative perspectives, analysis, experiences, strategies, and solutions do.

Many feminist, queer, and anti-racist organizers have pointed out that having women, people of color, or LGBTQ+ persons at the table does not necessarily lead to less militaristic solutions to international conflict or to disarmament. Under the Obama administration, for example, women held leadership positions throughout the national security and nuclear weapons establishment, yet the administration still objected vociferously to the banning of nuclear weapons and actively lobbied U.S. allies to reject the TPNW.

Although the call for gender equality is a welcome recognition of the significant exclusions in diplomacy and in governmental offices related to international security and weapons policy, it fails to acknowledge the power structures embedded in the institutions that limit discourse around weapons, militarism, and war. Instead, this call reinforces a men-women binary without acknowledging gender fluidity or nonconformity, does not address intersectional issues related to diversity of identity and experience, and does not examine why women and others need to be empowered to participate in the first place.

To advance the work that has been done by governments so far and to fully integrate feminist, queer, and anti-racist perspectives in disarmament diplomacy, action must be taken beyond calls for greater participation. The TPNW gender focal point, states-parties and signatories, activists, and academics should challenge states that resist the incorporation of gender perspectives, gender and racial diversity, and intersectional approaches in disarmament spaces and promote the TPNW as a progressive framework for these considerations.

They must facilitate the active participation of those who can bring lived experience and non-normative analysis of nuclear weapons. This could include funding participants’ travel to meetings, enabling virtual options for remote engagement, and ensuring that marginalized groups are included in implementing the 2022 action plan and developing further commitments.

Adopting an abolition framework can help facilitate this work. Abolition means seeking to deconstruct the systems and institutions that cause harm while simultaneously building up structures for equality, justice, and well-being. In the context of advancing gender and disarmament, this involves deconstructing gender and militarized masculinities to foster approaches that see disarmament as a positive force for change rather than a capitulation to power.

Dismantling militarized masculinities means refusing to buy into idealized notions of strong men and passive women, of men needing to be providers and protectors and women needing protection, and of states needing weapons and the ability to wage war. Rejecting the gender binary is essential to this work.

Rather than accepting a gendered or racialized dichotomy, nonbinary thinking facilitates different ways of solving problems such as nuclear violence or international security. Instead of us versus them, this approach posits that all states and all peoples and other living things share this planet and have a responsibility to care for each other and to collaborate in creating a better world. It enables the articulation and establishment of other forms of security based on peace and justice rather than violence.

TPNW states-parties should pursue these kinds of ideas to advance the burgeoning intersectional approach adopted in last year’s declaration and action plan. The nature of the process by which governments and activists engage to achieve nuclear disarmament, in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion of people and of perspectives, is important. It is largely because of leadership from women, queer people, and the global South that the TPNW was achieved at all. Their rejection of the nuclear-armed states’ binary conception of security was instrumental to the TPNW’s framing and success so far. This fundamental inclusivity and diversity of ideas and people must continue for the treaty to meet its full potential and abolish nuclear weapons forever.

ENDNOTES

1. Ray Acheson, “Notes on Nuclear Weapons & Intersectionality in Theory and Practice,” Princeton University Program on Science and Global Security, June 2022, https://sgs.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/2022-06/acheson-2022.pdf.

2. Carol Cohn, Felicity Ruby, and Sara Ruddick, “The Relevance of Gender for Eliminating Weapons of Mass Destruction,” Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, n.d., https://genderandsecurity.org/sites/default/files/the_relevance_of_gender_for_eliminating_weapons_of_mass_destruction_-_cohn_hill_ruddick.pdf (paper no. 38).

3. Ray Acheson, Banning the Bomb, Smashing the Patriarchy (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022).

4. See Ray Acheson, Richard Moyes, and Thomas Nash, “Sex and Drone Strikes: Gender and Identity in Targeting and Casualty Analysis,” Article 36 and Reaching Critical Will, October 2014, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/sex-and-drone-strikes.pdf.

5. See Gabriella Irsten, “Women and Explosive Weapons,” Reaching Critical Will, 2014, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/WEW.pdf.

6. See Gender and Radiation Impact Project, https://www.genderandradiation.org; Mary Olson, “Human Consequences of Radiation: A Gender Factor in Atomic Harm,” in Civil Society Engagement in Disarmament Processes: The Case for a Nuclear Weapons Ban (New York: UN Office for Disarmament Affairs, 2016), https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/civil-society-2016.pdf.

7. UN General Assembly, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, Calin Georgescu,” A/HRC/21/48/Add.1, September 3, 2012.

8. See Reiko Watanuki, Yuko Yoshida, and Kiyoko Futagami, “Radioactive Contamination and the Health of Women and Post-Chernobyl Children,” Chernobyl Health Survey and Healthcare for the Victims—Japan Women’s Network, 2006).

9. First Meeting of States-Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Vienna Action Plan,” TPNW/MSP/2022/CRP.7, June 22, 2022.

10. First Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Vienna Declaration of the 1st Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons: ‘Our Commitment to a World Free of Nuclear Weapons,’” TPNW/MSP/2022/CRP.8, June 23, 2022, p. 3.

11. Janene Yazzie, Facebook video message, June 22, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/janene.yazzie/videos/568148638000767.

12. ICAN Australia, “Statement From People Impacted by Nuclear Testing,” June 23, 2022, https://icanw.org.au/statement-nuclear-testing.

13. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Gender, Disarmament and Nuclear Weapons: Working Paper Submitted by Ireland,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.I/WP.38, May 9, 2017; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Impact and Empowerment—The Role of Gender in the NPT: Working Paper Submitted by Ireland,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/WP.38, April 24, 2018; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Gender in the NPT: Recommendations for the 2020 Review Conference; Working Paper Submitted by Ireland,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.48, May 7, 2019.

14. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Improving Gender Equality and Diversity in the Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Process: Working Paper Submitted by Australia, Canada, Ireland, Namibia, Sweden and the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.25, April 18, 2019; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Integrating Gender Perspectives in the Implementation of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Working Paper Submitted by Australia, Canada, Ireland, Namibia, Sweden and the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.27, April 18, 2019; 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “From Pillars to Progress: Gender Mainstreaming in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons; Working Paper Submitted by Australia, Canada, Colombia, Ireland, Mexico, Namibia, Panama, the Philippines, Spain, Sweden, and the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research,” NPT/CONF.2020/WP.54, May 17, 2022.

15. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Chairman’s Factual Summary,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.I/CRP.3, May 11, 2017.

16. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Chair’s Factual Summary,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/CRP.3, May 3, 2018.

17. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Recommendations to the 2020 Review Conference,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/CRP.4/Rev.1, May 9, 2019.

18. “Joint Statement on Gender, Diversity and Inclusion at the 10th NPT Review Conference,” n.d., https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/revcon2022/statements/4Aug_Gender.pdf.

19. Ray Acheson, “Report on Main Committee I,” NPT News in Review, Vol. 17, No. 7 (August 18, 2022), pp. 5–19, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/NIR2022/NIR17.7.pdf.

20. 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Draft Final Document,” NPT/CONF.2020/CRP.1/Rev.2, August 25, 2022.

Ray Acheson is director of Reaching Critical Will, the disarmament program of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and author of Banning the Bomb, Smashing the Patriarchy.

The failure to participate in the annual data exchange occurs as Russia is waging an illegal war against Ukraine, suspending its participation in the last treaty limiting Russian and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons and taking other steps to undermine the post-Cold War European security architecture.

The failure to participate in the annual data exchange occurs as Russia is waging an illegal war against Ukraine, suspending its participation in the last treaty limiting Russian and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons and taking other steps to undermine the post-Cold War European security architecture.

The May 19–21 gathering creates a crucial opportunity for Biden and his counterparts to recognize the horrors of nuclear war and reaffirm the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons while pledging concrete steps to halt the arms race, guard against nuclear weapons use, and advance nuclear disarmament. Anything less would be a failure of leadership at a time of nuclear peril.

The May 19–21 gathering creates a crucial opportunity for Biden and his counterparts to recognize the horrors of nuclear war and reaffirm the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons while pledging concrete steps to halt the arms race, guard against nuclear weapons use, and advance nuclear disarmament. Anything less would be a failure of leadership at a time of nuclear peril. Critically, Washington should seek to avert an unconstrained multilateral nuclear arms race that would be even more complicated and dangerous than the one during the Cold War. For the next decade, the United States should prioritize maintaining verifiable mutual limits with Russia on nuclear forces while deepening dialogue with China and aiming to bring it into bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control over the longer term. To prevent limitless arms races and avert nuclear catastrophe, it will be necessary to establish a measure of strategic stability globally and regionally among these three nuclear powers.

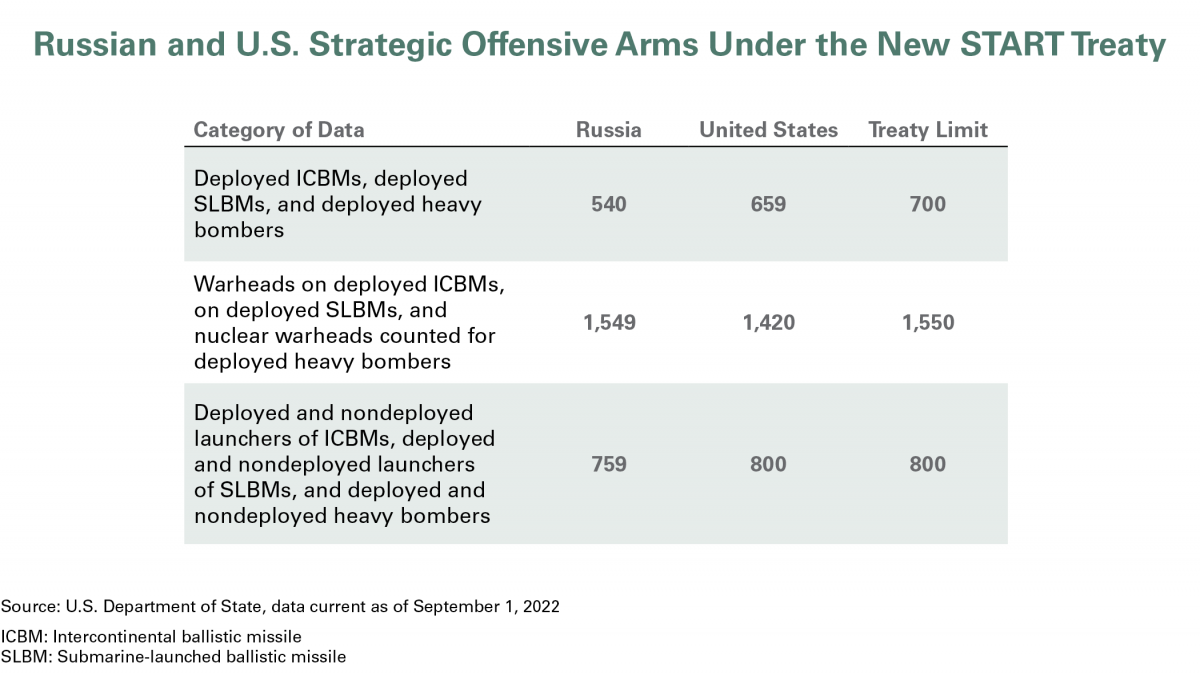

Critically, Washington should seek to avert an unconstrained multilateral nuclear arms race that would be even more complicated and dangerous than the one during the Cold War. For the next decade, the United States should prioritize maintaining verifiable mutual limits with Russia on nuclear forces while deepening dialogue with China and aiming to bring it into bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control over the longer term. To prevent limitless arms races and avert nuclear catastrophe, it will be necessary to establish a measure of strategic stability globally and regionally among these three nuclear powers. Moscow and Washington have since reaffirmed interest in a successor to New START, although each side’s conditions for resuming dialogue remain vague and have changed over time. In January 2023, the United States accused Russia of violating New START by failing to resume on-site inspections following an agreed two-year pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic and by failing to meet in the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the treaty’s implementing body.

Moscow and Washington have since reaffirmed interest in a successor to New START, although each side’s conditions for resuming dialogue remain vague and have changed over time. In January 2023, the United States accused Russia of violating New START by failing to resume on-site inspections following an agreed two-year pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic and by failing to meet in the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the treaty’s implementing body. Negotiations on a new treaty or other agreement to succeed New START will not be easy. The United States wants to include all the categories of weapons that the treaty limits plus Russia’s new novel strategic nuclear systems and places a high priority on adding nonstrategic nuclear warheads.

Negotiations on a new treaty or other agreement to succeed New START will not be easy. The United States wants to include all the categories of weapons that the treaty limits plus Russia’s new novel strategic nuclear systems and places a high priority on adding nonstrategic nuclear warheads. With the termination of the INF Treaty, there are no longer any constraints on nuclear-capable short- and intermediate-range land-based ballistic and cruise missiles, those having ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.

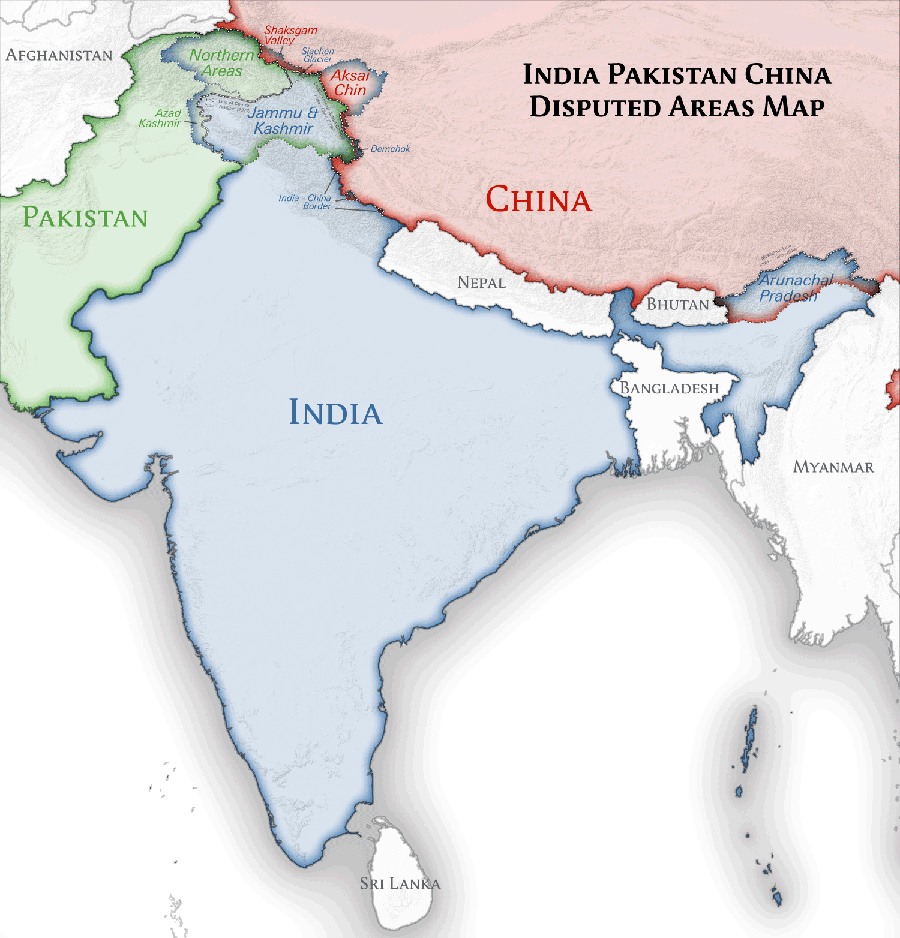

With the termination of the INF Treaty, there are no longer any constraints on nuclear-capable short- and intermediate-range land-based ballistic and cruise missiles, those having ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers. Beginning a dialogue on nuclear issues and agreeing on its scope will be challenging. U.S. policymakers are concerned by the opaque nature of Chinese nuclear plans, but leaders in Beijing perceive a narrow focus on nuclear weapons as a U.S. attempt to entrench the current numerical disparity and disadvantage China by seeking increased transparency about its much smaller nuclear force. Conversely, Washington perceives Beijing’s resistance to discussing Chinese nuclear weapons as a way to pursue nuclear competition without adopting the transparency and confidence-building measures that have contributed to strategic stability between Russia and the United States.

Beginning a dialogue on nuclear issues and agreeing on its scope will be challenging. U.S. policymakers are concerned by the opaque nature of Chinese nuclear plans, but leaders in Beijing perceive a narrow focus on nuclear weapons as a U.S. attempt to entrench the current numerical disparity and disadvantage China by seeking increased transparency about its much smaller nuclear force. Conversely, Washington perceives Beijing’s resistance to discussing Chinese nuclear weapons as a way to pursue nuclear competition without adopting the transparency and confidence-building measures that have contributed to strategic stability between Russia and the United States. The latter topic has received the most attention within recent disarmament forums, including those related to nuclear weapons. There is a stark disparity in the level (seniority or rank) and the number of men as compared to women in disarmament, nonproliferation, and arms control discussions, negotiations, and processes. Moreover, most discourse and action related to this subject have centered on a binary notion of gender and thus neglected the intersectionality of identities and oppressions that lead to the marginalization and exclusion of certain people.

The latter topic has received the most attention within recent disarmament forums, including those related to nuclear weapons. There is a stark disparity in the level (seniority or rank) and the number of men as compared to women in disarmament, nonproliferation, and arms control discussions, negotiations, and processes. Moreover, most discourse and action related to this subject have centered on a binary notion of gender and thus neglected the intersectionality of identities and oppressions that lead to the marginalization and exclusion of certain people. This includes engaging relevant stakeholders, including international organizations, civil society, affected communities, indigenous peoples, and youth, at all stages of the victim assistance and environmental remediation process; providing victim assistance that is age and gender sensitive; developing guidelines for voluntary reporting on national measures related to victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation; integrating gender considerations as the treaty is implemented; and considering the different needs of people in affected communities and Indigenous people.

This includes engaging relevant stakeholders, including international organizations, civil society, affected communities, indigenous peoples, and youth, at all stages of the victim assistance and environmental remediation process; providing victim assistance that is age and gender sensitive; developing guidelines for voluntary reporting on national measures related to victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation; integrating gender considerations as the treaty is implemented; and considering the different needs of people in affected communities and Indigenous people. In 2017, Ireland and Sweden presented research showing that women’s participation rate in NPT meetings is lower than in other multilateral forums. In 2019, both governments hosted side events at the NPT preparatory committee meeting related to gender and nuclear weapons. Ireland submitted working papers in 2017, 2018, and 2019 related to gender,

In 2017, Ireland and Sweden presented research showing that women’s participation rate in NPT meetings is lower than in other multilateral forums. In 2019, both governments hosted side events at the NPT preparatory committee meeting related to gender and nuclear weapons. Ireland submitted working papers in 2017, 2018, and 2019 related to gender, Some arms control advocates argue that accepting North Korea’s nuclear status would provide more tangible security benefits than the current U.S. policy of pushing for denuclearization. Jeffrey Lewis has asserted that this shift would remove the main impediment to bilateral talks and could help reduce the growing risks of an inadvertent conflict.

Some arms control advocates argue that accepting North Korea’s nuclear status would provide more tangible security benefits than the current U.S. policy of pushing for denuclearization. Jeffrey Lewis has asserted that this shift would remove the main impediment to bilateral talks and could help reduce the growing risks of an inadvertent conflict. Whether the United States accepts North Korea’s nuclear status or not, the extreme unlikelihood of North Korea giving up its nuclear deterrent anytime soon means that it will continue to occupy a sui generis category akin to the other three nuclear outliers—India, Israel, and Pakistan. In the case of acceptance, North Korea would be closer in terms of perception, treatment, and status to a country such as Pakistan, whose desire for nuclear recognition and trade is undermined by its record on nonproliferation.

Whether the United States accepts North Korea’s nuclear status or not, the extreme unlikelihood of North Korea giving up its nuclear deterrent anytime soon means that it will continue to occupy a sui generis category akin to the other three nuclear outliers—India, Israel, and Pakistan. In the case of acceptance, North Korea would be closer in terms of perception, treatment, and status to a country such as Pakistan, whose desire for nuclear recognition and trade is undermined by its record on nonproliferation. Some South Korean advocates of nuclear weapons believe that alliance deterrence capabilities and demonstrations of resolve, such as joint military exercises, need to be enhanced to counter the growing threat from North Korea. Some analysts have even suggested that South Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons would ensure a stronger alliance with the United States and prevent decoupling. As Cheong Seong-chang, a senior analyst at the Sejong Institute in South Korea, has argued, “If South Korea possesses nuclear weapons, the United States will not need to ask whether it should use its own weapons to defend its ally, and the alliance will never be put to a test.”

Some South Korean advocates of nuclear weapons believe that alliance deterrence capabilities and demonstrations of resolve, such as joint military exercises, need to be enhanced to counter the growing threat from North Korea. Some analysts have even suggested that South Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons would ensure a stronger alliance with the United States and prevent decoupling. As Cheong Seong-chang, a senior analyst at the Sejong Institute in South Korea, has argued, “If South Korea possesses nuclear weapons, the United States will not need to ask whether it should use its own weapons to defend its ally, and the alliance will never be put to a test.” Thomas Hughes, a long-time U.S. Department of State official in the 1960s who later became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a founding member of the board of directors of the Arms Control Association, died January 2 in Washington at the age of 97.

Thomas Hughes, a long-time U.S. Department of State official in the 1960s who later became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a founding member of the board of directors of the Arms Control Association, died January 2 in Washington at the age of 97. J

J Examining a Complex Nuclear Dynamic

Examining a Complex Nuclear Dynamic Interestingly, Tellis finds that all three countries are inclined toward conservative operational postures based on their underlying belief in deterrence by punishment. Despite the buildup of some capabilities that can help China and Pakistan adopt a strategy of deterrence by denial, neither country has abandoned the conviction that the fundamental utility of nuclear weapons lies in deterring nuclear attacks. This “enduring element” is a significant factor contributing to strategic stability in the region.

Interestingly, Tellis finds that all three countries are inclined toward conservative operational postures based on their underlying belief in deterrence by punishment. Despite the buildup of some capabilities that can help China and Pakistan adopt a strategy of deterrence by denial, neither country has abandoned the conviction that the fundamental utility of nuclear weapons lies in deterring nuclear attacks. This “enduring element” is a significant factor contributing to strategic stability in the region. The first issue is “India’s biggest nuclear deficiency,” which the author identifies as the “absence of reliable high-yield weapons in its inventory.” Based on data from India’s 1998 nuclear tests and subsequent assessments by scientists, he questions the weapons design base and argues that India does not have the “cutting-edge sophistication that would be needed for [weapons] reliability in real world conditions.” In order to validate advanced nuclear designs, Tellis believes India will feel the need to do a fresh round of testing and recommends that when this happens, the United States should not apply sanctions or suspend or terminate the Indian-U.S. nuclear deal. For the author, this would be “the best U.S. contribution toward enhancing geopolitical stability in the wider Asian region at a time when Chinese assertiveness will be increasingly harder to deter.” Given that China looms large on the U.S. threat radar, Tellis’ proposal is unsurprising, but it is not supported by any historical instance where the United States facilitated nuclear weaponization or testing even for its closest allies. It is doubtful that the suggestion will find traction with U.S. nonproliferation loyalists.

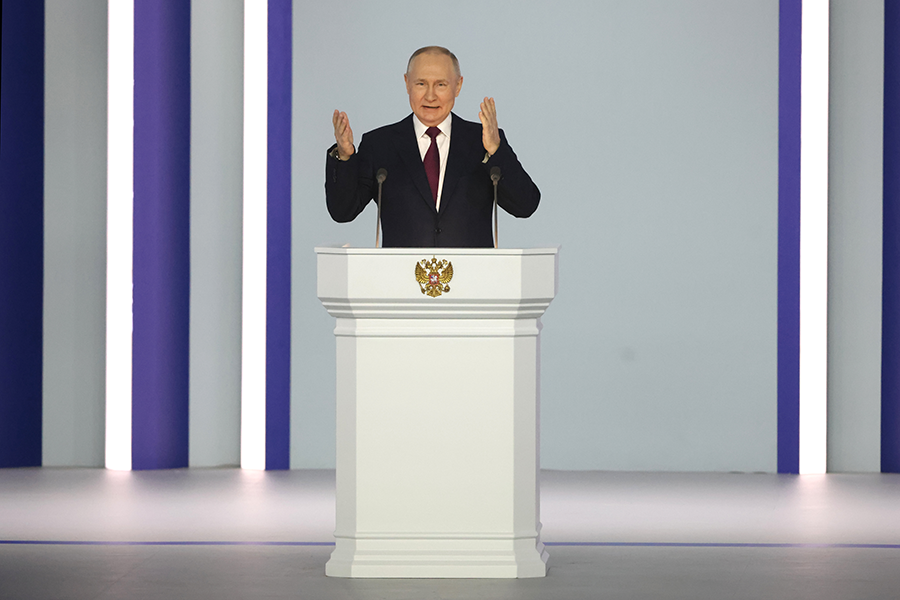

The first issue is “India’s biggest nuclear deficiency,” which the author identifies as the “absence of reliable high-yield weapons in its inventory.” Based on data from India’s 1998 nuclear tests and subsequent assessments by scientists, he questions the weapons design base and argues that India does not have the “cutting-edge sophistication that would be needed for [weapons] reliability in real world conditions.” In order to validate advanced nuclear designs, Tellis believes India will feel the need to do a fresh round of testing and recommends that when this happens, the United States should not apply sanctions or suspend or terminate the Indian-U.S. nuclear deal. For the author, this would be “the best U.S. contribution toward enhancing geopolitical stability in the wider Asian region at a time when Chinese assertiveness will be increasingly harder to deter.” Given that China looms large on the U.S. threat radar, Tellis’ proposal is unsurprising, but it is not supported by any historical instance where the United States facilitated nuclear weaponization or testing even for its closest allies. It is doubtful that the suggestion will find traction with U.S. nonproliferation loyalists. “I am compelled to announce today that Russia is suspending its participation” in New START, Putin said in a state-of-the-nation address to the Federal Assembly on Feb. 21. To resume treaty activities, the United States would need to cut off support for Ukraine and bring France and the United Kingdom into arms control talks, he said.

“I am compelled to announce today that Russia is suspending its participation” in New START, Putin said in a state-of-the-nation address to the Federal Assembly on Feb. 21. To resume treaty activities, the United States would need to cut off support for Ukraine and bring France and the United Kingdom into arms control talks, he said. Cara Abercrombie, coordinator for defense policy and arms control at the U.S. National Security Council, said on Feb. 1 that Russia’s noncompliance with New START “threatens the viability of U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control moving forward.” The treaty expires on Feb. 5, 2026, and a successor arms control arrangement does not exist at this time. This has deepened concern among experts that, in three years, the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals might go unconstrained for the first time since 1972.

Cara Abercrombie, coordinator for defense policy and arms control at the U.S. National Security Council, said on Feb. 1 that Russia’s noncompliance with New START “threatens the viability of U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control moving forward.” The treaty expires on Feb. 5, 2026, and a successor arms control arrangement does not exist at this time. This has deepened concern among experts that, in three years, the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals might go unconstrained for the first time since 1972. President Yoon Suk Yeol told officials in the South Korean Defense and Foreign Affairs ministries on Jan. 11 that if the threat posed by North Korea “gets worse,” it is possible that “our country will introduce tactical nuclear weapons or build them on our own.” He added that if the decision were made to develop nuclear weapons, Seoul could build them “pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.”

President Yoon Suk Yeol told officials in the South Korean Defense and Foreign Affairs ministries on Jan. 11 that if the threat posed by North Korea “gets worse,” it is possible that “our country will introduce tactical nuclear weapons or build them on our own.” He added that if the decision were made to develop nuclear weapons, Seoul could build them “pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.” Yoon’s comments come amid increasing tensions on the Korean peninsula and a significant expansion in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. North Korea conducted an unprecedented 69 ballistic missile tests in 2022, and South Korea responded to several of them by launching its own systems. North Korea also flew drones into South Korea in December, prompting the South to respond by sending its own drones into North Korea.

Yoon’s comments come amid increasing tensions on the Korean peninsula and a significant expansion in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. North Korea conducted an unprecedented 69 ballistic missile tests in 2022, and South Korea responded to several of them by launching its own systems. North Korea also flew drones into South Korea in December, prompting the South to respond by sending its own drones into North Korea. Russia attacked the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in March 2022 and continues to occupy the Ukrainian facility in violation of international law. (See

Russia attacked the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in March 2022 and continues to occupy the Ukrainian facility in violation of international law. (See