May 2018

By George Lewis and Frank von Hippel

Since President George W. Bush withdrew the United States from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002, the U.S. government has spent an average of $10 billion per year in today’s dollars on ballistic missile defense systems whose effectiveness is limited at best and whose deployment threatens the future of nuclear arms control with China and Russia.

Now, under pressure due to North Korean development of nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), Congress and the Trump administration are on the verge of throwing additional tens of billions of dollars into the same black hole. Indeed, the congressional appropriation for ballistic missile defense in fiscal year 2018 is the largest ever.

U.S. policy needs an overhaul. The problems with current U.S. policy fall into two realms: the political reactions of China and Russia and the technical emphasis on missile interception above the atmosphere. This article explains the problems and proposes an alternative approach.

U.S. policy needs an overhaul. The problems with current U.S. policy fall into two realms: the political reactions of China and Russia and the technical emphasis on missile interception above the atmosphere. This article explains the problems and proposes an alternative approach.

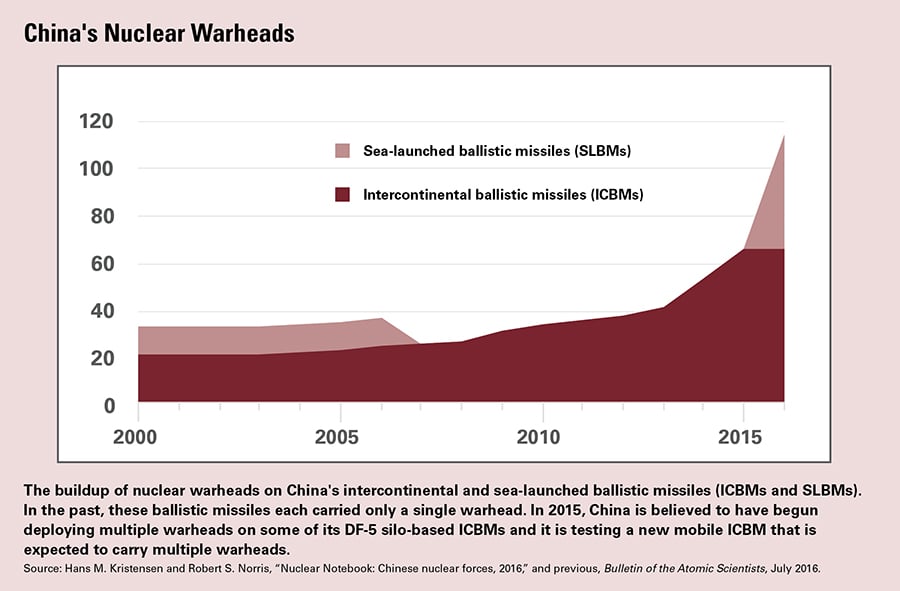

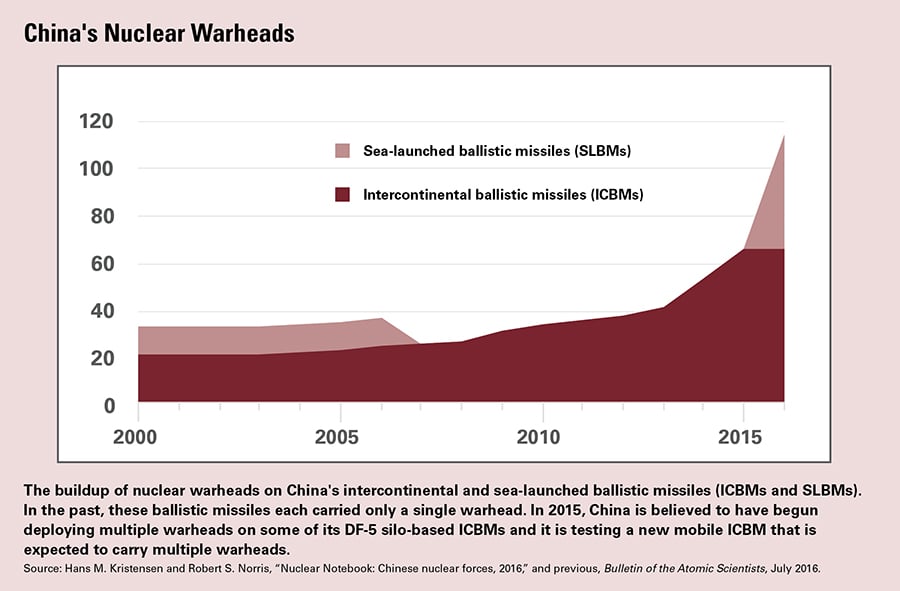

The current U.S. focus is on North Korea’s ballistic missiles. China and Russia, however, see U.S. ballistic missile defense systems as a potential threat to their nuclear deterrents. Their scientists understand that current U.S. systems can be countered with penetration aids, commonly known as countermeasures; but their policymakers worry that eventually these U.S. systems could become effective, especially if a U.S. first strike decimated their deterrent missiles. As a result, China is increasing the number of ballistic missile warheads that can reach the United States; Russia is unwilling to join the United States in further nuclear weapons reductions; and China and Russia are developing alternative warhead-delivery systems, such as hypersonic boost-glide weapons, that will further fuel a nuclear arms race.

The U.S. approach to ballistic missile defense emphasizes interception above the atmosphere, the longest portion of an ICBM warhead’s trajectory. Unfortunately, interception can be made particularly difficult here, posing high technical hurdles to success. Due to the absence of air resistance, lightweight countermeasures can be deployed that are indistinguishable from the warhead or can conceal its exact location from the defender’s detection systems.

Instead of continuing to apply the current flawed approach, an alternative policy consisting of more effective ballistic missile defenses against North Korea and diplomacy and arms control should be pursued. First, although countermeasures against above-the-atmosphere (exoatmospheric) defenses are within North Korea’s technical reach, the country is so small that interception of its ICBMs during the boost phase may be possible using fast interceptors based on or over international waters. Such an approach would not have the reach to threaten ICBMs currently based deep within China or Russia. Second, war with North Korea would be catastrophic for the people of North and South Korea, Japan, and quite possibly the United States. Although North Korea’s threats are appalling, there is little evidence that its leadership is suicidal. Diplomacy should be pursued to create a common understanding of the danger and avoid war in the near term, creating time for a long-term strategy for nuclear risk reduction in the region. Similarly, nuclear arms negotiations must begin with China and be revived with Russia. These negotiations almost certainly will have to include limitations on ballistic missile defenses.

Current U.S. Systems

For the purposes of discussing interception, it is convenient to divide the flight of an attacking ballistic missile into three phases. Boost phase involves the first minutes during which the payload is being accelerated by its rocket booster. Midcourse, after the booster burns out and its payload coasts through space on a ballistic trajectory, is in the vacuum of space and is the primary focus of current U.S. efforts against longer-range ballistic missiles. Terminal phase involves the last tens of seconds during which a missile or warhead plunges back through the atmosphere toward its target. Currently deployed U.S. ballistic missile defense systems target only the midcourse and terminal phases, although there has been interest in boost-phase interception since the 1950s.

U.S. ballistic missile defense systems are comprised of sensors, interceptors, and command-and-control systems that link the two. The ballistic missile tracking system starts with data from early-warning satellites in high-altitude orbits that detect the infrared emissions from missile-booster plumes and provide data on their launch points and approximate trajectories. Thereafter, radars are used to track the warheads. The long-range interceptors that defend the United States are guided primarily by five large, long-range, early-warning radars located in California, Cape Cod, Greenland, the United Kingdom, and Alaska, plus the Cobra Dane radar in the Aleutian Islands, which was originally built in the 1970s to observe the flight tests of Soviet ballistic missiles.

U.S. ballistic missile defense systems are comprised of sensors, interceptors, and command-and-control systems that link the two. The ballistic missile tracking system starts with data from early-warning satellites in high-altitude orbits that detect the infrared emissions from missile-booster plumes and provide data on their launch points and approximate trajectories. Thereafter, radars are used to track the warheads. The long-range interceptors that defend the United States are guided primarily by five large, long-range, early-warning radars located in California, Cape Cod, Greenland, the United Kingdom, and Alaska, plus the Cobra Dane radar in the Aleutian Islands, which was originally built in the 1970s to observe the flight tests of Soviet ballistic missiles.

All these radars have been upgraded to allow them to track ballistic missiles accurately enough to guide exoatmospheric interceptors. The wavelengths of their signals are too long, however, to measure the shapes of the objects that they are tracking in enough detail to discriminate between an actual attacking warhead and other similar-sized objects. In 2008 the U.S. Missile Defense Agency (MDA) deployed the sea-based X-band radar. Based in Honolulu, this radar system can sail to any desired location in the Pacific region. Although specifically built for target discrimination, it could be fooled by decoys or other midcourse countermeasures and has other serious deficiencies. Shorter-range interceptors are guided by their own shorter-range radars, although they can be cued by early-warning satellites and also potentially use data from other radars.

Currently, the United States has five deployed ballistic missile defense systems: the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD), Aegis BMD ships, Aegis Ashore, Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD), and Patriot systems.1 The current focus for U.S. homeland defense is the GMD system, whose deployment was initiated by the G.W. Bush administration to defend all U.S. states against ICBMs. By the end of 2017, a total of 44 interceptors were deployed, 40 at Fort Greely in Alaska and four at the Vandenberg Air Force Base missile flight-test site in California.

Each interceptor carries a homing exoatmospheric kill vehicle (EKV). Guided by the long-range radars, the booster propels the EKV into outer space toward its incoming target at a speed of about six kilometers (3.8 miles) per second. The EKV uses its infrared seeker and divert thrusters to maneuver itself into a direct, high-speed collision with its target.

Thus far, the GMD system has succeeded in killing its target warhead in only half of the 18 interception tests. Most of the failures have been due to quality control issues resulting from the rush to meet the politically motivated 2004 deadline for declaring the system operational. The problems with the EKV are so severe that the MDA has decided to replace the deployed EKVs with the Redesigned Kill Vehicle, starting in 2022.

The GMD system has cost about $40 billion to date, or $1 billion per deployed interceptor,2 but was assessed in June 2017 by the Department of Defense’s operational test and evaluation office to have only “demonstrated the capability to defend the U.S. Homeland from a small number of intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) or intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) threats with simple countermeasures.”3 This ambiguous statement does not mean the GMD system would be effective in actual use.

The Navy currently has about 85 Aegis destroyers and cruisers each equipped with four-faced SPY-1 phased-array radar systems and about 100 vertical launch tubes. In addition to ballistic missile defense interceptors, the launch tubes can carry anti-aircraft missiles, land-attack cruise missiles, and anti-submarine weapons. Thus far, more than 35 Aegis ships have been upgraded to be able to perform ballistic missile defense missions. The number is increasing at a rate of about four per year—two via upgrades of existing ships, two by new construction. By the mid-2030s, it is likely that the entire fleet will be capable of ballistic missile defense activities.

The Aegis missiles are variants of the Standard Missile-3 (SM-3). These are exoatmospheric interceptors with infrared-homing kill vehicles similar to but much smaller than the GMD interceptors. SM-3 Block I interceptors have a burnout speed of about three kilometers per second with a maximum intercept range of a few hundred kilometers, which is too low to defend a large area such as the United States. By 2019, however, the Navy plans to begin deployment of a new higher-speed Block IIA interceptor being co-developed with Japan. With a burnout speed of about 4.5 kilometers per second, it could defend the entire United States from a small number of offshore and onshore locations, using the long-range GMD radars for determining approximate intercept points. Congress has recently mandated that the Block IIA missile be tested against an ICBM by the end of 2020 “if technologically feasible.”4

The Navy also has developed a land-based version known as Aegis Ashore. One such facility is operational in Romania, and a second is being built in Poland. Both projects were launched early in the Obama administration when there was concern that Iran, like North Korea, might acquire nuclear weapons and longer-range ballistic missiles. These Aegis Ashore bases have infuriated Russia, which claims that they could be used to forward-base cruise missiles in violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Yet, the United States is not reconsidering their deployment, despite the constraints Iran has accepted on its nuclear program and its self-imposed 2,000-kilometer-range limit on its ballistic missiles.5

The United States operates an Aegis Ashore test facility in Hawaii that could be converted into an operational facility to defend against North Korean ICBMs. Japan, which operates six Aegis ships and plans two more, has recently announced its intention to build two Aegis Ashore facilities to guard against North Korean missiles. The United States has recently begun deploying Standard Missile-6 interceptors on Aegis ships, which can intercept shorter-range missiles in their terminal phase.

The THAAD and Patriot systems are terminal-phase ballistic missile defense systems designed to intercept attacking missiles in the atmosphere as they descend toward their targets. The THAAD system also can operate just above the atmosphere. Patriot missiles are intended for use against shorter-range missiles and aircraft. Although the areas that THAAD and Patriot batteries could protect would be much too small for them to be used to defend the entire United States, THAAD missiles could be used as a second layer of defense for metropolitan areas. It is deployed in South Korea and Guam.

Reliability Versus Operational Effectiveness

The GMD intercept test May 30, 2017, cost $244 million.6 It would be extremely costly to conduct enough intercept tests to cover the full range of possible battle conditions, including credible countermeasures. Therefore, intercept tests for midcourse systems essentially are highly scripted demonstrations to validate simulations. When they fail, it is usually because of a quality-control failure in the hardware. The GMD system has failed half of its 18 intercept tests. The Aegis system has done better, with an 82 percent success rate in SM-3 Block I intercept tests, but the Block IIA has failed in two of its three intercept tests.

Establishing that a given ballistic missile defense system can work reliably against targets under ideal conditions (e.g., during the day with the sun behind the kill vehicle illuminating a target unaccompanied by serious penetration aids) is only the first step toward establishing the operational effectiveness of the system. The fundamental question is how well these systems would work in actual combat conditions when unexpected circumstances and enemy countermeasures must be addressed.

The experience of the Patriot Advanced Capability-2 system highlights the difference between reliability on the test range and operational effectiveness in battle. Although it was reportedly successful in all 17 of its prewar intercept tests, it failed nearly completely during the 1991 Persian Gulf War in 44 engagements against Iraqi Scud missiles that had characteristics quite different from the targets against which it had been tested.7

Midcourse Countermeasures

The challenge of exoatmospheric countermeasures has been part of the public discussion of ballistic missile defense for 50 years. In the absence of air resistance, light and heavy objects travel on indistinguishable trajectories in outer space. Warheads can be concealed in clouds of radar-reflecting chaff or inside aluminized balloons, and decoys can be constructed of very lightweight materials. The temperatures and therefore the infrared signatures of objects also can be manipulated in outer space by varying their surface coatings or by adding small battery-powered or chemical heat sources inside.

All five of the original nuclear-weapon states have developed countermeasures for their long-range nuclear-armed ballistic missiles.8 Many countermeasures are simple enough such that a 1999 U.S. National Intelligence Estimate concluded that

[m]any countries, such as North Korea, Iran, and Iraq probably would rely initially on readily available technology—including separating [re-entry vehicles (RVs)], spin-stabilized RVs, RV reorientation, radar absorbing material (RAM), booster fragmentation, low-power jammers, and simple (balloon) decoys—to develop penetration aids and countermeasures…. These countries could develop countermeasures based on these technologies by the time they flight test their missiles.9

A 2012 study by the National Academy of Sciences found, however, that the MDA had abandoned significant efforts to deal with countermeasures.

Based on the information presented to it by the Missile Defense Agency (MDA), the committee learned very little that would help resolve the discrimination issue in the presence of sophisticated countermeasures. In fact, the committee had to seek out people who had put together experiments…and who had understood and analyzed the data gathered. Their funding was terminated several years ago, ostensibly for budget reasons, and their expertise was lost. When the committee asked MDA to provide real signature data from all flight tests, MDA did not appear to know where to find them.10

Details about the testing of U.S. interceptors against countermeasures are highly classified, but there is no public indication of change in the fundamental fact that, because of their susceptibility to countermeasures, ballistic missile defense systems requiring exoatmospheric interception can promise little in the way of effective defense. Building and deploying them wastes billions of dollars that could be used more effectively on other activities, including potentially more effective types of ballistic missile defense.

One way to force the MDA to acknowledge the countermeasure problem would be to establish an independent testing team to equip target missiles with penetration aids considered within the reach of North Korea. Indeed, a congressionally mandated 2010 study of countermeasures by JASON, a high-level independent technical review panel, recommended such an approach. The MDA tried to suppress the report.11

Stimulating Offensive Buildups

In addition to high costs and doubtful effectiveness, exoatmospheric ballistic missile defense systems can have serious adverse effects on U.S. security. One is to undercut Russia’s willingness to reduce further the number of its nuclear warheads or consider taking its missiles off hair-trigger alert.

In the wake of the Cold War, Washington and Moscow agreed to deep cuts in their deployed strategic weapons. Even after the United States began deploying its GMD system in 2004, the two countries were able to reduce weapons levels further, to 1,550 deployed strategic warheads under the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). This last reduction was possible only because the U.S. GMD system initially had very limited objectives and was deployed slowly. The goal of 30 interceptors was achieved only in 2010, and the total number reached 44 only at the end of 2017.

Galvanized by the threat of North Korean nuclear-armed ICBMs, the United States is now embarking on a much larger and more rapid expansion of ballistic missile defense systems. Congress has recently approved funds to deploy an additional 20 GMD interceptors by 2023 and to plan for a further increase to at least 104 interceptors.12 Planned qualitative improvements to the GMD system include the deployment of multiple, small kill vehicles on GMD boosters and a new discrimination radar.13 More importantly, in terms of numbers of long-range interceptors, the number of SM-3 Block IIA interceptors with their theoretical capabilities to intercept strategic missiles could climb to between 300 and 400 or more by the 2030s, with deployments on 80 to 90 ships and at Aegis Ashore sites.

The congressional mandate that the SM-3 Block IIA interceptors be tested against an ICBM will almost certainly increase Russian and Chinese perceptions of threat to the deterrent value of their strategic ballistic missile forces. Congress has acknowledged this problem by requiring that the Pentagon assess whether testing the SM-3 Block IIA against ICBMs would undermine the nuclear deterrence capabilities of nuclear-armed adversaries other than North Korea.14

When it signed New START in April 2010, Russia stipulated that a buildup of U.S. missile defenses could be grounds for Moscow to withdraw. At that time, Russia had nearly 50 times more strategic nuclear ballistic missile warheads than the United States had strategic-capable interceptors. Even without taking into account losses from a hypothetical U.S. first strike, that ratio will soon fall into the single digits. At best, therefore, the expansion of the GMD system and the large-scale deployment of SM-3 Block IIA interceptors on Aegis ships would lock the United States and Russia into the current New START levels for the indefinite future.

The U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup may already be provoking China to augment its strategic offensive forces. China has been increasing the number of its ICBMs, begun deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and is developing ICBMs with multiple warheads, actions widely viewed as being at least in part a response to the U.S. ballistic missile defense program. China also may be moving away from its historical practice of deploying its missiles separately from their nuclear warheads to protect against accidental or unauthorized launch, and Russia and China are developing alternative delivery systems, including hypersonic boost-glide vehicles that cannot be intercepted by current or planned U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. Furthermore, they could respond to U.S. actions by accelerating their own missile defense programs, increasing the danger of a destabilizing, three-sided offense-defense competition.

The U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup may already be provoking China to augment its strategic offensive forces. China has been increasing the number of its ICBMs, begun deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and is developing ICBMs with multiple warheads, actions widely viewed as being at least in part a response to the U.S. ballistic missile defense program. China also may be moving away from its historical practice of deploying its missiles separately from their nuclear warheads to protect against accidental or unauthorized launch, and Russia and China are developing alternative delivery systems, including hypersonic boost-glide vehicles that cannot be intercepted by current or planned U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. Furthermore, they could respond to U.S. actions by accelerating their own missile defense programs, increasing the danger of a destabilizing, three-sided offense-defense competition.

Despite the availability of countermeasures to the systems that the United States is deploying today, the ultimate driver of Russian and Chinese offensive counters to the U.S. ballistic missile defense program is that it is completely open-ended. There is no indication of when or if the process of expanding and layering of defenses will end.

Boost-Phase Missile Defense

Boost-phase missile defense offers a technical fix to the problem of North Korean ICBMs and provides a potential avenue to address some Russian and Chinese concerns. Although ballistic missile defense advocates are reluctant to admit how easily midcourse defenses could be defeated, some tacitly acknowledge the problem by promoting boost-phase defenses. Countermeasures are much less of a problem for boost-phase interception than for midcourse interception because, for instance, a decoy would have to have a full-size operational rocket booster.

The technical challenge is that the boost phase is only a few minutes long. Therefore, the defense must be deployed close to the attacking missile’s launch site, although obviously it cannot be stationed within the target country’s airspace. For surface- or air-based interceptors or drone-borne lasers, these constraints limit the feasibility of defenses against ICBMs to launches from small countries, such as North Korea. One benefit is that such boost-phase defenses would be much less threatening to land-based ICBMs deep in the interiors of large countries such as Russia or China and therefore would be less likely to trigger an offense-defense competition.

Currently, the MDA’s only boost-phase program is an effort to deploy electrically driven lasers on high-altitude drones.15 Such a system faces many technical challenges and, even if they are overcome, would not be operational until the mid-2020s.

Given the urgency of the North Korean threat, an approach that uses small, high-acceleration, high-speed interceptors on drones or ships could provide a boost-phase capability earlier. One notional system would deploy such interceptors on Predator drones based in South Korea. The drones would patrol roughly 100 kilometers off North Korea’s east and west coasts. A preliminary analysis indicates that two such interceptors could be carried on a Predator B drone.16

If developed as an expedited Defense Department program using existing technologies, such a boost-phase defense could potentially be operational within three years. Its advantages would include reducing political pressures to expand the GMD system, with its counterproductive effects on the future of nuclear arms control with China and Russia. Although North Korea might eventually be able to build faster-burning, solid-fueled boosters that would be more difficult for this boost-phase system to counter, it takes many years to master the technology of large solid-fueled boosters, buying time for diplomacy.

It is not as clear that such an alternative system would reduce the demand for SM-3 Block IIA interceptors. Although they could be used to defend U.S. territory, they are justified primarily as defenses against shorter-range missiles aimed at U.S. allies and carrier battle groups. Boost-phase defenses would be less effective against shorter-range missiles because they have shorter boost times.

Preventing deployments of the SM-3 Block IIA interceptor from halting or even reversing progress in reducing nuclear weapons will thus likely require quantitative limits on its deployment. The current political environment would seem to rule out a formal treaty imposing such limits, but a recognition by the United States of the long-term consequences of unlimited SM-3 Block IIA deployments might lead it to some restraint in deployment. Although the SM-3 Block IIA has some significant advantages over the SM-3 Block IB, a mixed force comprised mostly of SM-3 Block IBs would also have advantages, in particular a significantly lower cost that could allow the acquisition of greater numbers of interceptors.

If reduced numbers of SM-3 Block IIA interceptors were combined with other measures, such as limits on testing against long-range missiles, it might significantly reduce Russian and Chinese concerns and their responses to deployment. Interceptor speed and testing limits were discussed with Russia during the Clinton administration as a way to deal with Russia’s concerns about U.S. theater missile defenses, and it was agreed that interceptors having a burnout speed of less than three kilometers per second, that is, the speed of the SM-3 Block I interceptors, would be of little concern if they were not tested against targets with the speeds of strategic missiles.17

The confluence of Iran’s announcement on constraining its missile ranges and the congressional mandate to examine the implications of SM-3 Block IIA interceptor deployments on other countries’ deterrent capabilities may present an opportunity to reconsider its deployment. An imporant first step would be to reverse the congressional requirement to test the interceptor against an ICBM.

Outlook

The best alternative to continuing on the current trajectory of the U.S. ballistic missile defense program would be a combination of diplomacy and arms control. In the 16 years since President George W. Bush withdrew the country from the ABM Treaty, the United States has spent about $150 billion in today’s dollars on ballistic missile defenses.18 That expenditure has produced systems susceptible to countermeasures that are within the technological reach of North Korea. It has also revived the arms race with Russia and provoked a Chinese offensive buildup.

Perhaps it is time to try something else. The alternative approach that made it possible to end the Cold War nuclear buildup was arms control, starting with the ABM Treaty. Perhaps that would be a good place to start again. In fact, the United States has not moved far from the limits of the ABM Treaty and the 1997 theater missile defense demarcation agreement with Russia. The United States has fewer than 100 long-range interceptors and has not yet begun to deploy theater missile interceptors with burnout speeds greater than three kilometers per second. Perhaps it is not too late.

ENDNOTES

1. “FY16 Ballistic Missile Defense Systems,” n.d., p. 408, http://www.dote.osd.mil/pub/reports/FY2016/pdf/bmds/2016bmds.pdf.

2. David Willman, “Pentagon Successfully

Tests Missile Defense System Amid Rising Concerns About North Korea,” Los Angeles Times, May 30, 2017.

3. “FY17 Ballistic Missile Defense Systems,” n.d., p. 279, http://www.dote.osd.mil/pub/reports/FY2017/pdf/bmds/2017bmds.pdf.

4. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, H.R. Rep. No. 115-404, sec. 1680 (2017) (Conf. Rep.) (hereinafter 2018 defense authorization conference report).

5. Nasser Karimi and Jon Gambrell, “Iran’s Supreme Leader Limits Range for Ballistic Missiles Produced Locally,” Associated Press, October 31, 2017.

6. Justin Doubleday, “Pentagon Delays First Salvo Test of GMD System,” Inside Defense SITREP, June 1, 2017.

7. George N. Lewis and Theodore A. Postol, “Patriot Performance in the Gulf War,” Science and Global Security, Vol. 8 (2000), pp. 315–356; Jeremiah D. Sullivan et al., “Technical Debate Over Patriot Performance in the Gulf War,” Science and Global Security, Vol. 8 (1999), pp. 41–98.

8. Andrew M. Sessler et al., “Countermeasures: A Technical Evaluation of the Operational Effectiveness of the Planned U.S. National Missile Defense System,” Union of Concerned Scientists, April 2000, pp. 35–37, 145–148, http://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/legacy/assets/documents/nwgs/cm_all.pdf.

9. U.S. National Intelligence Council, “Foreign Missile Developments and the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States Through 2015,” September 1999, https://fas.org/irp/threat/missile/nie99msl.htm.

10. National Research Council, “Making Sense of Ballistic Missile Defense: An Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile Defense in Comparison to Other Alternatives,” National Academies Press, September 2012, pp. 10, 21, 131.

11. JASON, “MDA Discrimination,” JSR-10-620, August 3, 2010, https://fas.org/irp/agency/dod/jason/mda-dis.pdf (unclassified summary). The report gives no indication that any solution to the discrimination problem has been found.

12. 2018 defense authorization conference report, sec. 1686.

13. John Keller, “Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Refine MOKV Missile Defense to Kill Several Warheads With One Launch,” Military Aerospace Electronics, April 5, 2017, http://www.militaryaerospace.com/articles/2017/04/missile-defense-to-kill-several-warheads-at-once.html.

14. 2018 defense authorization conference report, pp. 1032–1033.

15. Mostlymissiledefense, “Chronology of MDA’s Plans for Laser Boost-Phase Defense,” August 26, 2016, https://mostlymissiledefense.com/2016/08/26/chronology-of-mdas-plans-for-laser-boost-phase-defense-august-26-2016/.

16. Richard L. Garwin and Theodore A. Postol, “Airborne Patrol to Destroy DPRK ICBMs in Powered Flight,” n.d., https://fas.org/rlg/airborne.pdf

17. Amy F. Woolf, “Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty Demarcation and Succession Agreements: Background and Issues,” CRS Report for Congress, 98-496 F, April 27, 2000.

18. U.S. Missile Defense Agency, “Historical Funding for MDA FY85-17,” n.d., https://www.mda.mil/global/documents/pdf/FY17_histfunds.pdf.

George Lewis, a physicist, is a visiting scholar at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University. Frank von Hippel is a senior research physicist and professor emeritus of public and international affairs at Princeton University, where he co-founded the Program on Science and Global Security.

Now, in an extraordinary turnaround, an uneasy détente has emerged. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un announced on Jan. 1 that he wants to ease tensions with South Korea, and high-level talks between officials of the two governments were held in advance of the Winter Olympics. Through South Korean intermediaries, Kim extended a summit offer to U.S. President Donald Trump, who, to the surprise of many, immediately accepted. Although Trump deserves credit for being so bold as to agree, the North Korean nuclear problem will not be resolved in one meeting, especially if he goes off-script, acts impulsively, or carries unrealistic expectations.

Now, in an extraordinary turnaround, an uneasy détente has emerged. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un announced on Jan. 1 that he wants to ease tensions with South Korea, and high-level talks between officials of the two governments were held in advance of the Winter Olympics. Through South Korean intermediaries, Kim extended a summit offer to U.S. President Donald Trump, who, to the surprise of many, immediately accepted. Although Trump deserves credit for being so bold as to agree, the North Korean nuclear problem will not be resolved in one meeting, especially if he goes off-script, acts impulsively, or carries unrealistic expectations.

The critics seem to have a point, at least for now, as massive nuclear modernization programs, faltering arms control measures, and nuclear brinksmanship harken back to the Cold War era. Yet, the Vatican tends to play the long game. Given its influence as a norm entrepreneur on nuclear weapons and a major transnational actor headed by an influential pope, the critics might want to pay attention.

The critics seem to have a point, at least for now, as massive nuclear modernization programs, faltering arms control measures, and nuclear brinksmanship harken back to the Cold War era. Yet, the Vatican tends to play the long game. Given its influence as a norm entrepreneur on nuclear weapons and a major transnational actor headed by an influential pope, the critics might want to pay attention. Integral disarmament assumes that the long-term goal of abolishing nuclear weapons has to be part of a much larger cosmopolitan project of developing a global ethic of peace and solidarity that can ground a system of cooperative security. A realist approach that prioritizes a negative peace, defined largely in terms of military security and balance of power, is based on a mentality of fear and the false security of weapons of mass destruction. Nuclear weapons are an impediment to the kind of cooperative security needed to build a positive peace based on a host of factors: socioeconomic development, political participation, respect for fundamental human rights, strong international norms and institutions, a spirit of dialogue, solidarity in international relations, as well as a change of hearts.

Integral disarmament assumes that the long-term goal of abolishing nuclear weapons has to be part of a much larger cosmopolitan project of developing a global ethic of peace and solidarity that can ground a system of cooperative security. A realist approach that prioritizes a negative peace, defined largely in terms of military security and balance of power, is based on a mentality of fear and the false security of weapons of mass destruction. Nuclear weapons are an impediment to the kind of cooperative security needed to build a positive peace based on a host of factors: socioeconomic development, political participation, respect for fundamental human rights, strong international norms and institutions, a spirit of dialogue, solidarity in international relations, as well as a change of hearts. Whether Kim may be willing to disarm and what he will want in return is a matter of mere speculation. Concrete proposals for reciprocal steps and diplomatic give-and-take is the only way to find out.

Whether Kim may be willing to disarm and what he will want in return is a matter of mere speculation. Concrete proposals for reciprocal steps and diplomatic give-and-take is the only way to find out. Arms Control Today in mid-April asked two experts on U.S.-North Korean diplomacy to share some of their views looking ahead to a meeting. Jenny Town is assistant director of the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and managing editor of the website 38 North, which analyzes North Korean developments. Frank Jannuzi is president and CEO of the Mansfield Foundation and a former policy director for East Asian and Pacific affairs for the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Arms Control Today in mid-April asked two experts on U.S.-North Korean diplomacy to share some of their views looking ahead to a meeting. Jenny Town is assistant director of the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and managing editor of the website 38 North, which analyzes North Korean developments. Frank Jannuzi is president and CEO of the Mansfield Foundation and a former policy director for East Asian and Pacific affairs for the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee. U.S. policy needs an overhaul. The problems with current U.S. policy fall into two realms: the political reactions of China and Russia and the technical emphasis on missile interception above the atmosphere. This article explains the problems and proposes an alternative approach.

U.S. policy needs an overhaul. The problems with current U.S. policy fall into two realms: the political reactions of China and Russia and the technical emphasis on missile interception above the atmosphere. This article explains the problems and proposes an alternative approach. U.S. ballistic missile defense systems are comprised of sensors, interceptors, and command-and-control systems that link the two. The ballistic missile tracking system starts with data from early-warning satellites in high-altitude orbits that detect the infrared emissions from missile-booster plumes and provide data on their launch points and approximate trajectories. Thereafter, radars are used to track the warheads. The long-range interceptors that defend the United States are guided primarily by five large, long-range, early-warning radars located in California, Cape Cod, Greenland, the United Kingdom, and Alaska, plus the Cobra Dane radar in the Aleutian Islands, which was originally built in the 1970s to observe the flight tests of Soviet ballistic missiles.

U.S. ballistic missile defense systems are comprised of sensors, interceptors, and command-and-control systems that link the two. The ballistic missile tracking system starts with data from early-warning satellites in high-altitude orbits that detect the infrared emissions from missile-booster plumes and provide data on their launch points and approximate trajectories. Thereafter, radars are used to track the warheads. The long-range interceptors that defend the United States are guided primarily by five large, long-range, early-warning radars located in California, Cape Cod, Greenland, the United Kingdom, and Alaska, plus the Cobra Dane radar in the Aleutian Islands, which was originally built in the 1970s to observe the flight tests of Soviet ballistic missiles.

The U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup may already be provoking China to augment its strategic offensive forces. China has been increasing the number of its ICBMs, begun deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and is developing ICBMs with multiple warheads, actions widely viewed as being at least in part a response to the U.S. ballistic missile defense program. China also may be moving away from its historical practice of deploying its missiles separately from their nuclear warheads to protect against accidental or unauthorized launch, and Russia and China are developing alternative delivery systems, including hypersonic boost-glide vehicles that cannot be intercepted by current or planned U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. Furthermore, they could respond to U.S. actions by accelerating their own missile defense programs, increasing the danger of a destabilizing, three-sided offense-defense competition.

The U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup may already be provoking China to augment its strategic offensive forces. China has been increasing the number of its ICBMs, begun deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and is developing ICBMs with multiple warheads, actions widely viewed as being at least in part a response to the U.S. ballistic missile defense program. China also may be moving away from its historical practice of deploying its missiles separately from their nuclear warheads to protect against accidental or unauthorized launch, and Russia and China are developing alternative delivery systems, including hypersonic boost-glide vehicles that cannot be intercepted by current or planned U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. Furthermore, they could respond to U.S. actions by accelerating their own missile defense programs, increasing the danger of a destabilizing, three-sided offense-defense competition.

My concern is that the United States must be prepared, that the president must be prepared, and I worry sometimes that he’s not very prepared. I’ve been to North Korea eight times, and the North Koreans are disciplined, they’re prepared, they’re very inflexible, and they’re very formal. When you negotiate with them, they have their talking points, they vent, they’re hostile. They want you to listen to them, to show respect. Then, you respond. The key is on the sidelines, the informal. That’s where you make a personal connection. That’s where, maybe, you make a deal with them on detainees, on return of remains of U.S. servicemen, on an issue relating to food. It’s always informal. They don’t make it at the negotiating table. For that, Trump needs to be patient, restrained, and prepared.

My concern is that the United States must be prepared, that the president must be prepared, and I worry sometimes that he’s not very prepared. I’ve been to North Korea eight times, and the North Koreans are disciplined, they’re prepared, they’re very inflexible, and they’re very formal. When you negotiate with them, they have their talking points, they vent, they’re hostile. They want you to listen to them, to show respect. Then, you respond. The key is on the sidelines, the informal. That’s where you make a personal connection. That’s where, maybe, you make a deal with them on detainees, on return of remains of U.S. servicemen, on an issue relating to food. It’s always informal. They don’t make it at the negotiating table. For that, Trump needs to be patient, restrained, and prepared. Those steps by the Kim regime, however welcome, fall short of what the United States has considered to be denuclearization. The Trump administration regards denuclearization as meaning North Korea “no longer having nuclear weapons that can be used in warfare against any of our allies,” White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said on April 22.

Those steps by the Kim regime, however welcome, fall short of what the United States has considered to be denuclearization. The Trump administration regards denuclearization as meaning North Korea “no longer having nuclear weapons that can be used in warfare against any of our allies,” White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said on April 22. Specifically, North Korea called in 2016 for disclosure of any U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea, guarantees the United States will not redeploy nuclear weapons in South Korea, assurance it will not conduct a nuclear strike on North Korea, and withdrawal of U.S. troops authorized to use nuclear weapons. Although the United States does not deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea, South Korea and Japan are covered by the U.S. extended nuclear deterrent, and strategic assets are used in joint military drills.

Specifically, North Korea called in 2016 for disclosure of any U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea, guarantees the United States will not redeploy nuclear weapons in South Korea, assurance it will not conduct a nuclear strike on North Korea, and withdrawal of U.S. troops authorized to use nuclear weapons. Although the United States does not deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea, South Korea and Japan are covered by the U.S. extended nuclear deterrent, and strategic assets are used in joint military drills. Victims reported the distinct scent of chlorine gas, a banned choking agent. But medical responders reported that victims’ symptoms, including frothing at the mouth, were consistent with exposure to a prohibited nerve agent. The United States estimates that Syria has used various types of chemical weapons at least 50 times, U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley told the UN Security Council on April 13. (See

Victims reported the distinct scent of chlorine gas, a banned choking agent. But medical responders reported that victims’ symptoms, including frothing at the mouth, were consistent with exposure to a prohibited nerve agent. The United States estimates that Syria has used various types of chemical weapons at least 50 times, U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley told the UN Security Council on April 13. (See  Anita Friedt, acting assistant secretary of state for arms control, verification, and compliance, told the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting April 19 that an extension “is something we’re looking at” but that there is no target date for the completion of the review. Friedt added that the administration will take into account Russian compliance with other arms control agreements when weighing whether to extend New START. The United States has accused Russia of being in violation of several arms control treaties and commitments, most notably the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

Anita Friedt, acting assistant secretary of state for arms control, verification, and compliance, told the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting April 19 that an extension “is something we’re looking at” but that there is no target date for the completion of the review. Friedt added that the administration will take into account Russian compliance with other arms control agreements when weighing whether to extend New START. The United States has accused Russia of being in violation of several arms control treaties and commitments, most notably the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.