May 2021

By Cristina Chaplain

Each new administration has reshaped the U.S. missile defense vision and architecture to align with its perception of changing threats, technological advancements, program setbacks, budgets, and political considerations. The Biden administration will likely do the same. One of the most important questions the new administration will face is the direction to take with homeland defense.

The Department of Defense is already on a path to acquire a new interceptor for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is the only system designed to defend the United States against a limited intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) attack from North Korea and Iran. Yet, there are questions about the extent to which the United States should rely on the GMD system given the changing threat, the system’s troubled development and expense, and the need to fund new programs such as those focused on new hypersonic threats and tracking missiles from space.

The Department of Defense is already on a path to acquire a new interceptor for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is the only system designed to defend the United States against a limited intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) attack from North Korea and Iran. Yet, there are questions about the extent to which the United States should rely on the GMD system given the changing threat, the system’s troubled development and expense, and the need to fund new programs such as those focused on new hypersonic threats and tracking missiles from space.

Moreover, there are questions about the role the Missile Defense Agency (MDA), which is responsible for developing U.S. missile defenses, should be playing. Over the years, the agency has transitioned from one focused largely on advancing technology to one now largely focused on procurement and production. Congress and the secretary of defense have also been considering whether systems now in production or fielded should be transferred to the service branches, as originally planned or remain with the MDA for the foreseeable future and whether MDA programs should have more oversight.

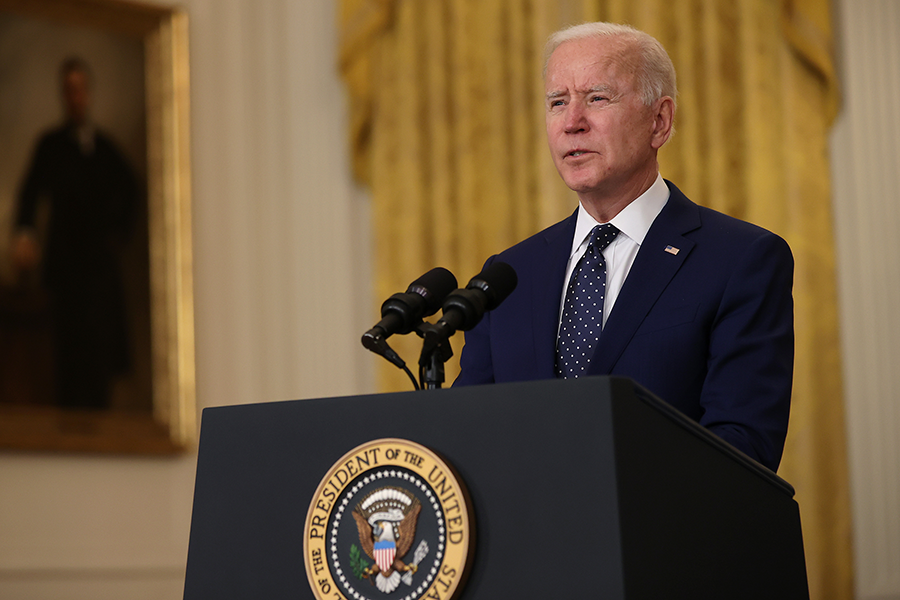

The work of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), a non-partisan investigative arm of Congress, does not involve making or proposing policy, and the GAO must be independent. Nevertheless, it has a lot to offer on policy execution, including regarding the missile defense program. Thirty years of working for this agency, including directing its reviews of missile defense for over a decade, have convinced me of that. Getting the rocket science correct will be important no matter which path President Joe Biden chooses for missile defense. To this end, there are some lessons to be learned from the GMD program.

Fly Before You Buy

If there is one lesson the MDA should take from the GMD program, it is to fly before you buy. That means making sure the system works before firing up the production lines and putting new interceptors into the ground. Specifically, technology invention should be done before design, and design should be done before production. Program managers and senior leaders should use quantifiable data and demonstrable knowledge to make decisions on cost, schedule, technology readiness, design readiness, production readiness, and relationships with suppliers. The GAO has repeatedly seen these practices contribute to success in the private sector and in government.1

The GMD program did not follow this model. Shortly after its inception in 2002, the MDA was directed by President George W. Bush to deploy an initial set of missile defense capabilities by 2004. Given considerable flexibility and authority to do so, the GMD program concurrently matured technology, designed the system, tested the design, and produced and fielded a system. Although this approach allowed the program to rapidly field a limited defense, it resulted in cost increases, schedule delays, test problems, and performance shortfalls. This “rush to fielding” mandate became a more or less pervasive part of the GMD culture.

The GAO raised concerns about this approach in 2003. It warned that critical technologies would not work as intended in planned flight tests, and would result in the MDA spending additional funds to identify and correct problems by September 2004 or accept a less capable system.2 In subsequent years, the GAO documented numerous setbacks in the GMD program, many due to avoidable errors. Although problems are expected in any sophisticated endeavor, the issues are how and when then they are discovered. In the GMD program, it happened late in development, when the errors are more expensive and time consuming to fix.

In 2006, for example, the GAO reported that interceptor production slowed because of technical problems, mostly in the kill vehicle. These were traced back to poor oversight of subcontractors, too few qualification tests, and other quality assurance issues.3 In 2010, a flight test failed because of design problems with the kill vehicle’s inertial measurement unit for the interceptor. At the time of the discovery, 12 of 23 interceptors had been manufactured and delivered even though a successful flight test had not yet happened. The cost to fix and flight-test the weapon increased from $236 million to nearly $2 billion as a result of the need to conduct failure reviews, additional flight tests, mitigation development efforts, and a retrofit program.4

Quality was a persistent problem, partly due to the rush to deliver. In one case, a flight test in 2010 failed because a lockwire in the kill vehicle was not installed. The following year, a GAO review found the GMD program had to cancel a major flight test due to flaws in a telemetry unit that were discovered during final assembly. GMD officials told the GAO that in the process of accelerating the GMD schedule, they became inattentive to weaknesses in the program’s quality control procedures.5

Some problems were not necessarily the fault of the GMD program itself, but were indicative of the program’s willingness to take risks. A flight test in 2007, for example, was unsuccessful because the target missile failed. The GAO has frequently recommended that the MDA test targets before flight tests, but this was often not done because of expediency.

Some problems were not necessarily the fault of the GMD program itself, but were indicative of the program’s willingness to take risks. A flight test in 2007, for example, was unsuccessful because the target missile failed. The GAO has frequently recommended that the MDA test targets before flight tests, but this was often not done because of expediency.

The GMD program’s most recent effort to update the interceptor, known as the Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV), started out with plans incorporating knowledge from the GMD program. Yet, the new kill vehicle program also ended up accepting too much risk and experiencing development challenges that set it back four years and increased costs by at least $600 million.

The RKV was intended to be more reliable, producible, testable, and cost effective, partly by using a modular open architecture that would make future upgrades easier and broaden the vendor and supply base. Among other actions, MDA plans called for conducting more flight testing before production. In 2016, the GAO viewed the plans as a positive indication of the MDA’s intent to improve its acquisition outcomes. Still, the GAO cautioned that the schedule was aggressive and questioned whether the MDA was allowing enough time for modifying and maturing technologies.6

In 2017, the MDA, responding to the growing North Korean missile threat, accelerated development while reducing the number of flight tests. The GAO found that the new plan was more likely to prolong the RKV effort rather than accelerate it. That was inconsistent with the fly-before-you-buy best practice because the MDA would begin production based on the results of design reviews rather than flight testing. The GAO reported that the RKV program was already experiencing development delays prior to the acceleration of the schedule and was operating with no schedule margin.7

The most significant development issue that emerged for the RKV in 2018 pertained to the planned use of commercial, off-the-shelf hardware and reuse of components from the Aegis system’s newest interceptor. In multiple reports, the GAO, along with some in the Defense Department, raised concerns about the use of these components as well as the aggressive schedule for the RKV. Facing time delays, cost increases, and design challenges, the Defense Department canceled the RKV program in August 2019. By then, the MDA had spent a total of $1.2 billion on development, which was $340 million more than the agency’s original estimate.8

In 2020, the agency began developing a next-generation ground-based interceptor for the GMD program. It recently awarded two contracts, with an estimated maximum value of $1.6 billion, to Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman to carry two designs into the technology development and risk reduction phase of the program. The MDA plans to execute two intercept flight tests before starting interceptor production and to base decisions on knowledge about technical and design maturity rather than on some arbitrary schedule. It plans to reduce technical risk with early testing of interceptor parts and is considering having the government take a more direct role in the program rather than relying on the prime contractor to determine the technical direction of the program, as it did with Boeing.9

These are hopeful signs that the MDA may have finally learned the fly-before-you-buy lesson. The GAO recently found that the approach the MDA is using to assess progress is in line with best practices. Promoting competition in the GMD program, particularly through design, could reduce cost and encourage industry innovation. Earlier testing of parts is another GAO-recommended practice that could enable the MDA to address problems with parts without major disruptions to the program, but the GMD program’s history provides only cautious optimism.

Be Transparent

The flexibilities granted the MDA so it could meet the presidentially mandated deadline for an initial homeland defense capability also came at the expense of transparency and accountability. For example, unlike other major weapons programs, cost, schedule, and performance baselines did not have to be established or approved outside the MDA. In addition, most major weapons programs were required by statute to obtain an independent verification of cost estimates, but the MDA was not.

Compounding matters, until 2011 the MDA had employed at least three different processes to track its acquisitions. The different structures for reporting cost, schedule, and performance data exacerbated transparency and accountability challenges. Each time a process changed, the connections between the old and new planned scope and resources were obscured.

In 2011, the GAO testified that the lack of baselines for missile defense, along with high levels of uncertainty about requirements and program cost estimates, effectively set the missile defense program on a path to an undefined destination at an unknown cost. There was limited knowledge and few opportunities for crucial management oversight and decision-making concerning the agency’s investment and the warfighter’s continuing needs.10

Over the past two decades, the MDA has made incremental progress in providing Congress and others with information needed for decision-making. In response to congressional direction, for example, the MDA established resource, schedule, test, operational capacity, technical, and contract baselines for its systems. It established processes for reviewing baselines and approving product development and initial production jointly with the service branches that will ultimately be responsible for those assets. It began producing independent cost estimates. Although these are positive steps, the GAO has made additional recommendations to strengthen these processes. For example, the MDA requests a billion dollars or more in funding each fiscal year for tests, but the GAO analysis found that these estimates were inconsistent and difficult to trace. The GAO recommended detailed changes to each test in the master test plan. It also recommended improvements to the process used to calculate cost estimates for tests.11

Moreover, the GAO reported in 2020 that more work needs to be done in terms of providing clarity into testing progress. The MDA frequently revises its test schedule by adding new tests and deleting or delaying scheduled tests, in some cases multiple times. As a result, less testing is being conducted prior to delivery than originally planned, which means less data are available to understand capabilities and limitations. The GAO recommended the MDA have an independent assessment conducted for its process for developing and executing its annual flight-test plan.12

Engage Stakeholders

Since the early 2000s, the MDA has had a reputation for going its own way and being somewhat adversarial with and unresponsive to Defense Department entities that had a stake in missile defense. These include members of the war-fighting community who were the ultimate customers of MDA-developed systems, the testing community, the acquisition oversight functions within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the intelligence community, and the service branches.

In a 2008 study on the mission, roles, and structure of the MDA led by the Institute of Defense Analyses for the Defense Department, the military raised concerns about inadequate visibility into planning, programming, and budgeting; insufficient involvement in the requirements process; and insufficient attention to integrating missile defense capabilities with other joint forces. The Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the combatant commands believed warfighters needed a stronger role in setting requirements for missile defense while officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense believed that the MDA should be merged with normal acquisition processes, while retaining sufficient flexibility to respond to a wider range of threats and technology opportunities. They asked for earlier involvement in the agency’s planning efforts and independent analysis to help ensure that trade-offs were adequately examined and evaluated.13

Although MDA flexibilities remain in place, the Defense Department has acted to increase the agency’s cooperation with its stakeholders. For example, the department established the Missile Defense Executive Board in 2007 to bring together senior Defense Department executives, representatives of the Department of State, and national security staff to review and provide guidance for missile defense. In 2008, the deputy secretary of defense created processes that enabled the military, the Joint Staff, the combatant commands, and other directorates within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to participate in and influence the development of the annual MDA program plan and budget submittal. Further, in June 2009 the MDA adopted a new approach toward test planning that integrated recommendations made by the Defense Department’s director of operational test and evaluation, among others.

Although MDA flexibilities remain in place, the Defense Department has acted to increase the agency’s cooperation with its stakeholders. For example, the department established the Missile Defense Executive Board in 2007 to bring together senior Defense Department executives, representatives of the Department of State, and national security staff to review and provide guidance for missile defense. In 2008, the deputy secretary of defense created processes that enabled the military, the Joint Staff, the combatant commands, and other directorates within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to participate in and influence the development of the annual MDA program plan and budget submittal. Further, in June 2009 the MDA adopted a new approach toward test planning that integrated recommendations made by the Defense Department’s director of operational test and evaluation, among others.

Those were all important steps, but the RKV program demonstrated that more was needed. In 2017 the GAO found that the MDA requirements-setting process tended to put the needs of the developer ahead of those of the warfighter. Designs for the RKV and other new systems included trade-offs that favored fielding capabilities sooner and less expensively. Officials from multiple entities within the Defense Department warned that these trade-offs compromised performance and reliability, which could leave warfighters with weapons that were insufficient to defeat current and future threats.

A 2021 GAO report documented program meetings in 2010, 2015, 2017, and 2018 in which subject matter experts and officials within and outside of the RKV program raised concerns about performance issues that went unheeded.14 Concerns about reusing a component from the Aegis interceptor along with commercial, off-the-shelf parts were so serious that the program was ultimately cancelled in 2019.

More broadly, the GAO has recently recommended that the MDA increase its collaboration with the defense intelligence community. Although it had taken some steps to do so, a 2019 review found that the MDA provides the intelligence community with limited insight into how the agency uses threat assessments to inform its acquisition decisions. That is a serious failing given that the intelligence community is uniquely positioned to assist the MDA and its involvement is crucial for helping the MDA to keep pace with rapidly emerging threats. Moreover, this limited insight has prevented the intelligence community from validating threat models that the agency builds to test the performance of its weapon systems. Without validation, any flaws or bias in the threat models may go undetected, which can have significant implications on the performance of MDA weapons systems.15

In 2021 the GAO reported that the MDA was working closely with stakeholders on the next-generation interceptor’s requirements and acquisition strategy and on implementing specific GAO recommendations on collaboration. For example, the agency engaged the defense intelligence community in producing an analysis of alternatives to defend against new hypersonic glide vehicles. Over the past several years, officials from several Defense Department organizations have told the GAO that MDA engagement with their organizations was improving.16 The GAO’s own relationship with the agency improved under the two most recent MDA directors.

Last year, the deputy secretary of defense took additional action to involve more participants in the oversight of missile defense programs, such as requiring the Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation to provide independent cost estimates before MDA program development and production decisions are made. Also, more oversight would be given to the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment and less to the undersecretary of defense for research and engineering. The MDA director stated that the directive essentially codifies what the MDA has already been doing.17

Sustain Support for Lessons Learned

The steps the MDA is taking are encouraging, but adopting and sustaining an effective knowledge-based acquisition approach will be challenging. For example, more resources may be needed to mature technology, carry two contractors through design, and ensure the government can play a stronger role in overseeing the program. Yet, those funding dollars may be difficult to find given overall budgetary concerns and the need to fund the MDA’s new hypersonic and other programs.

Moreover, pressures to proceed quickly, whether they are rooted in threats, budgets, politics, industry, or all of the above, will not go away. In fact, proceeding quickly and streamlining acquisition oversight is now in vogue for the broader weapons community because it is believed the development process most weapons systems follow takes too long and hampers innovation. At the direction of Congress, decision-making for many major defense acquisition programs has been shifted from the Office of the Secretary of Defense to the service branches. The Defense Department has also begun using new pathways referenced as “middle-tier acquisition” to rapidly produce prototypes and field some new weapons systems within two to five years. It is unknown how successful these programs will be, and it may stay that way given that the Defense Department has not yet fully determined how to measure performance.

It would be prudent for the Biden administration to insist that the MDA follow better acquisition practices for the next-generation interceptor versus stepping on the gas pedal. The agency already faces a steep technical challenge in developing a homeland missile defense system that can keep pace with the threat. The past has shown that rushing programs into production merely exacerbates the inherent technical challenges the MDA already faces, resulting in delays, added costs, and questionable performance.

That is not to say that following best practices for the next-generation interceptor will enable the Pentagon to fully protect the homeland from an ICBM attack. The United States is still in the beginning phases of addressing a very complex problem, and the threat will assuredly adapt and evolve. There are technical hurdles beyond the next interceptor that need to be overcome, such as maturing a discrimination capability, making testing more operationally realistic, and ensuring that supporting systems are seamlessly integrated. There are also broader questions to be answered about what can really be expected from the GMD system and what are the best investments for addressing the threat. Until those questions are answered, it is best to make sure this new interceptor can do its job as intended.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Best Practices: Better Support of Weapon System Program Managers Needed to Improve Outcomes,” GAO-06-110, November 30, 2005, pp. 5–10.

2. GAO, “Missile Defense: Knowledge-Based Practices Are Being Adopted, but Risks Remain,” GAO-03-441, April 30, 2003, p. 20.

3. GAO, “Defense Acquisitions: Missile Defense Agency Fields Initial Capability but Falls Short of Original Goals,” GAO-06-327, March 15, 2006, p. 11.

4. GAO, “Missile Defense: Opportunity Exists to Strengthen Acquisitions by Reducing Concurrency,” GAO-12-486, April 20, 2012, p. 74; GAO, “Missile Defense: Opportunities Exist to Reduce Acquisition Risk and Improve Reporting on System Capabilities,” GAO-15-345, May 6, 2015, p. 63.

5. GAO, “Space and Missile Defense Acquisitions: Periodic Assessment Needed to Correct Parts Quality Problems in Major Programs,” GAO-11-404, June 24, 2011; GAO, “Defense Acquisitions,” pp. 27-30.

6. GAO, “Missile Defense: Assessment of DOD's Reports on Status of Efforts and Options for Improving Homeland Missile Defense,” GAO-16-254R, February 17, 2016.

7. GAO, “Missile Defense: The Warfighter and Decision Makers Would Benefit From Better Communication About the System's Capabilities and Limitations,” GAO-18-324, May 30, 2018, p. 72.

8. GAO, “Missile Defense: Delivery Delays Provide Opportunity for Increased Testing to Better Understand Capability,” GAO-19-387, June 6, 2019, pp. 60-61; GAO, “Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist,” GAO-20-432, July 23, 2020, pp. 61–63.

9. GAO, “Missile Defense: Observations on Ground-Based Midcourse Defense Acquisition Challenges and Potential Contract Strategy Changes,” GAO-21-135R, October 21, 2020.

10. GAO, “Missile Defense: Actions Needed to Improve Transparency and Accountability,” GAO-11-555T, April 13, 2011.

11. Ibid.; GAO, “Missile Defense: Cost Estimating Practices Have Improved, and Continued Evaluation Will Determine Effectiveness,” GAO-15-210R, December 12, 2014.

12. GAO, “Missile Defense: Some Progress Delivering Capabilities, but Challenges With Testing Transparency and Requirements Development Need to Be Addressed,” GAO-17-381, May 30, 2017; GAO, “Missile Defense: Lessons Learned From Acquisition Efforts,” GAO-20-490T, March 12, 2020.

13. Gen. Larry D. Welch and David Briggs, “Study on the Mission, Roles, and Structure of the Missile Defense Agency (MDA),” Institute for Defense Analyses Paper, No. P-4374 (2008), ch. IV.

14. GAO, “Missile Defense: Some Progress Delivering Capabilities, but Challenges With Testing Transparency and Requirements Development Need to Be Addressed,” pp. 49-69; GAO, “Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist,” pp. 61–62.

15. GAO, “Missile Defense: Further Collaboration With the Intelligence Community Would Help MDA Keep Pace With Emerging Threats,” GAO-20-177, December 11, 2019.

16. GAO, “Missile Defense: Lessons Learned From Acquisition Efforts,” p. 6; GAO, “Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist,” p. 14.

17. Jen Judson, “New Pentagon Directive Will Put Programs on More Solid Ground, Says MDA Boss,” Defense News, September 10, 2020.

Cristina Chaplain retired in 2020 after working 30 years for the U.S. Government Accountability Office, a nonpartisan investigative agency for Congress. For more than a decade, she directed the agency’s reviews of missile defense programs.

In remarks April 15, Biden said his proposed summit meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin could be a launching point for talks on strategic stability and nuclear arms control. Serious, sustained disarmament diplomacy is overdue and essential, but achieving new agreements will be challenging.

In remarks April 15, Biden said his proposed summit meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin could be a launching point for talks on strategic stability and nuclear arms control. Serious, sustained disarmament diplomacy is overdue and essential, but achieving new agreements will be challenging.

President Joe Biden has an opportunity to mitigate this threat as he and his administration consider a Pentagon spending plan that is on track to invest $500 billion to maintain and replace the U.S. nuclear arsenal through 2028. One major decision involves the future of ICBMs.

President Joe Biden has an opportunity to mitigate this threat as he and his administration consider a Pentagon spending plan that is on track to invest $500 billion to maintain and replace the U.S. nuclear arsenal through 2028. One major decision involves the future of ICBMs. The ICBM Lobby: ICBM Contractors

The ICBM Lobby: ICBM Contractors Many of the lobbyists who work on behalf of ICBM contractors have passed through the “revolving door” from work in top governmental posts to work in the arms industry. For example, Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the next-generation ICBM, employed 51 lobbyists, in house and for hire, in 2020, 41 of whom came from positions in government. Prominent examples of revolving-door hires in that group have included Howard P. “Buck” McKeon, former California Republican chairman of the House Armed Services Committee; G. Stewart Hall, the former legislative director for Senator Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), who is the ranking member on the Appropriations Committee; and Bud Cramer, a former Democratic representative from Alabama who served on the appropriations defense subcommittee and was a strong advocate for defense-related activities. Others are Jonathan Etherton, who once was a Senate Armed Services Committee professional staff member, and Shay Michael Hancock, a former staffer for Senator Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who serves on the Budget Committee. Hancock also worked for House Armed Services Committee Chairman Adam Smith (D-Wash.).

Many of the lobbyists who work on behalf of ICBM contractors have passed through the “revolving door” from work in top governmental posts to work in the arms industry. For example, Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the next-generation ICBM, employed 51 lobbyists, in house and for hire, in 2020, 41 of whom came from positions in government. Prominent examples of revolving-door hires in that group have included Howard P. “Buck” McKeon, former California Republican chairman of the House Armed Services Committee; G. Stewart Hall, the former legislative director for Senator Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), who is the ranking member on the Appropriations Committee; and Bud Cramer, a former Democratic representative from Alabama who served on the appropriations defense subcommittee and was a strong advocate for defense-related activities. Others are Jonathan Etherton, who once was a Senate Armed Services Committee professional staff member, and Shay Michael Hancock, a former staffer for Senator Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who serves on the Budget Committee. Hancock also worked for House Armed Services Committee Chairman Adam Smith (D-Wash.). The Department of Defense is already on a path to acquire a new interceptor for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is the only system designed to defend the United States against a limited intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) attack from North Korea and Iran. Yet, there are questions about the extent to which the United States should rely on the GMD system given the changing threat, the system’s troubled development and expense, and the need to fund new programs such as those focused on new hypersonic threats and tracking missiles from space.

The Department of Defense is already on a path to acquire a new interceptor for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is the only system designed to defend the United States against a limited intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) attack from North Korea and Iran. Yet, there are questions about the extent to which the United States should rely on the GMD system given the changing threat, the system’s troubled development and expense, and the need to fund new programs such as those focused on new hypersonic threats and tracking missiles from space. Some problems were not necessarily the fault of the GMD program itself, but were indicative of the program’s willingness to take risks. A flight test in 2007, for example, was unsuccessful because the target missile failed. The GAO has frequently recommended that the MDA test targets before flight tests, but this was often not done because of expediency.

Some problems were not necessarily the fault of the GMD program itself, but were indicative of the program’s willingness to take risks. A flight test in 2007, for example, was unsuccessful because the target missile failed. The GAO has frequently recommended that the MDA test targets before flight tests, but this was often not done because of expediency. Although MDA flexibilities remain in place, the Defense Department has acted to increase the agency’s cooperation with its stakeholders. For example, the department established the Missile Defense Executive Board in 2007 to bring together senior Defense Department executives, representatives of the Department of State, and national security staff to review and provide guidance for missile defense. In 2008, the deputy secretary of defense created processes that enabled the military, the Joint Staff, the combatant commands, and other directorates within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to participate in and influence the development of the annual MDA program plan and budget submittal. Further, in June 2009 the MDA adopted a new approach toward test planning that integrated recommendations made by the Defense Department’s director of operational test and evaluation, among others.

Although MDA flexibilities remain in place, the Defense Department has acted to increase the agency’s cooperation with its stakeholders. For example, the department established the Missile Defense Executive Board in 2007 to bring together senior Defense Department executives, representatives of the Department of State, and national security staff to review and provide guidance for missile defense. In 2008, the deputy secretary of defense created processes that enabled the military, the Joint Staff, the combatant commands, and other directorates within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to participate in and influence the development of the annual MDA program plan and budget submittal. Further, in June 2009 the MDA adopted a new approach toward test planning that integrated recommendations made by the Defense Department’s director of operational test and evaluation, among others. In 1998, Sweden co-authored a joint declaration calling for a new agenda for nuclear disarmament and deploring the fact that “countless resolutions and initiatives [with respect to the elimination] of nuclear weapons in the past half century remain unfulfilled.”

In 1998, Sweden co-authored a joint declaration calling for a new agenda for nuclear disarmament and deploring the fact that “countless resolutions and initiatives [with respect to the elimination] of nuclear weapons in the past half century remain unfulfilled.” Linde: We have been happy to note strong interest for the initiative from other countries that are NPT states-parties. Several countries have chosen to align with the stepping stones proposals that were agreed in Berlin in February last year and we hope that more will follow. In any case, we hope that the initiative will be considered an effective method to achieve further disarmament and that our proposals can help stimulate discussion.

Linde: We have been happy to note strong interest for the initiative from other countries that are NPT states-parties. Several countries have chosen to align with the stepping stones proposals that were agreed in Berlin in February last year and we hope that more will follow. In any case, we hope that the initiative will be considered an effective method to achieve further disarmament and that our proposals can help stimulate discussion. Linde: First of all, we regret that the UK is set to increase the cap on its nuclear arsenal and no longer provide public figures on operational stockpiles, deployed warheads, and deployed missiles. I believe this to be a clear step in the wrong direction, at a time when our focus should be on achieving progress on disarmament ahead of the review conference. It adds to a deeply worrying trend, with also China increasing and diversifying its arsenal and with major modernization efforts going on elsewhere, not least in Russia. We must do everything in our power to avoid a costly and dangerous arms race.

Linde: First of all, we regret that the UK is set to increase the cap on its nuclear arsenal and no longer provide public figures on operational stockpiles, deployed warheads, and deployed missiles. I believe this to be a clear step in the wrong direction, at a time when our focus should be on achieving progress on disarmament ahead of the review conference. It adds to a deeply worrying trend, with also China increasing and diversifying its arsenal and with major modernization efforts going on elsewhere, not least in Russia. We must do everything in our power to avoid a costly and dangerous arms race. The scientists feared for the future. Faced with the nuclear threat, the committee proclaimed, “there is no possibility of control except through the aroused understanding and insistence of the peoples of the world.” They began fundraising, with a goal of $1 million (about $10 million in today’s dollars), and published leaflets, gave lectures and talks in person and on the radio, and supported some of the first documentary films on nuclear weapons issues. The group disbanded in 1951, and Einstein died in April 1955. One legacy is that physicists have inherited a special credibility and responsibility for nuclear issues, perhaps more than we deserve.

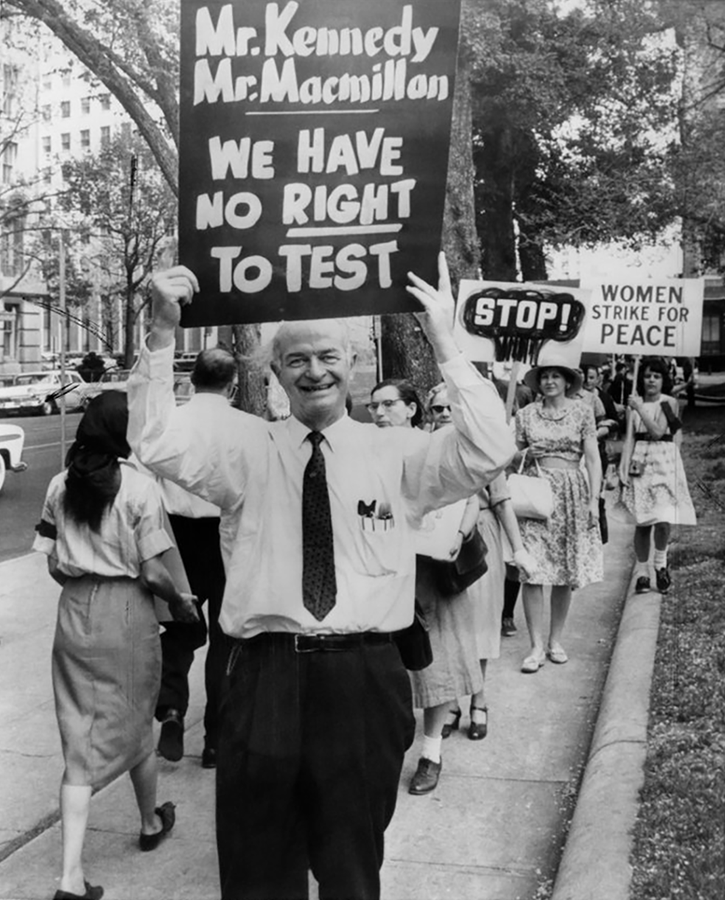

The scientists feared for the future. Faced with the nuclear threat, the committee proclaimed, “there is no possibility of control except through the aroused understanding and insistence of the peoples of the world.” They began fundraising, with a goal of $1 million (about $10 million in today’s dollars), and published leaflets, gave lectures and talks in person and on the radio, and supported some of the first documentary films on nuclear weapons issues. The group disbanded in 1951, and Einstein died in April 1955. One legacy is that physicists have inherited a special credibility and responsibility for nuclear issues, perhaps more than we deserve. A decade later, with the public aroused by the Army’s proposal to put nuclear-armed interceptors for Soviet ballistic missiles in the suburbs, Congress listened to the arguments of scientist critics that the defenses being proposed could easily be blinded and overwhelmed by the Soviets. That led to the 1972 Soviet-U.S. treaty limiting anti-ballistic missile defenses and the offense-defense arms race that had already been triggered.

A decade later, with the public aroused by the Army’s proposal to put nuclear-armed interceptors for Soviet ballistic missiles in the suburbs, Congress listened to the arguments of scientist critics that the defenses being proposed could easily be blinded and overwhelmed by the Soviets. That led to the 1972 Soviet-U.S. treaty limiting anti-ballistic missile defenses and the offense-defense arms race that had already been triggered. Iran, the five other members of the deal, and the United States have spent most of April in the Austrian capital discussing ways to restore the accord. An Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman confirmed on April 20 that work is underway on a document outlining steps that Iran and the United States must take to return to compliance. Negotiators aim to have a concrete proposal by mid-May, Reuters reported.

Iran, the five other members of the deal, and the United States have spent most of April in the Austrian capital discussing ways to restore the accord. An Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman confirmed on April 20 that work is underway on a document outlining steps that Iran and the United States must take to return to compliance. Negotiators aim to have a concrete proposal by mid-May, Reuters reported. The decision, adopted April 21 by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), marked a historic step toward restoring the global norm against chemical weapons. It was the first time the organization had suspended a member’s rights since the OPCW’s inception in 1997.

The decision, adopted April 21 by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), marked a historic step toward restoring the global norm against chemical weapons. It was the first time the organization had suspended a member’s rights since the OPCW’s inception in 1997. “I genuinely struggle with the credibility” of the Army’s plan to develop the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, Air Force Gen. Timothy M. Ray, chief of the Global Strike Command, said April 1 on an Air Force Association podcast. “I just think it’s a stupid idea to go invest that kind of money to re-create something that [the Air Force] has mastered,” he said.

“I genuinely struggle with the credibility” of the Army’s plan to develop the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, Air Force Gen. Timothy M. Ray, chief of the Global Strike Command, said April 1 on an Air Force Association podcast. “I just think it’s a stupid idea to go invest that kind of money to re-create something that [the Air Force] has mastered,” he said. The test vehicle was meant to launch from a B-52 bomber, but “the test missile was not able to complete its launch sequence,” and the bomber returned to Edwards Air Force Base in California, according to an Air Force statement.

The test vehicle was meant to launch from a B-52 bomber, but “the test missile was not able to complete its launch sequence,” and the bomber returned to Edwards Air Force Base in California, according to an Air Force statement. When concluding work on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and military appropriations bill for fiscal year 2021, Congress voted to scrub $370 million from the $464 million requested by the Pentagon for the procurement of unmanned surface vessels and demanded more testing before approving any additional funds for the program.

When concluding work on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and military appropriations bill for fiscal year 2021, Congress voted to scrub $370 million from the $464 million requested by the Pentagon for the procurement of unmanned surface vessels and demanded more testing before approving any additional funds for the program.