November 2022

By Monica Montgomery

The Russian war on Ukraine has led to significant increases in U.S. defense spending this year in terms of direct war-related expenditures and the Pentagon’s base budget. Even before the war, however, the push to invest more in defense had been advancing with the backing of a majority in Congress concerned about rising threats from Russia and China. The conflict in Ukraine is certain to have a profound impact on this trend.

The areas of defense spending that need reevaluating in this new environment raise major questions with which Washington urgently needs to grapple. The challenge for lawmakers is clear. They must unlearn the ways in which defense spending has been determined in recent years, based on fuzzy strategies and bad-faith arguments by those who stand to benefit from a bloated defense budget, and relearn how to focus the spending on real security requirements and fixed goals.

The areas of defense spending that need reevaluating in this new environment raise major questions with which Washington urgently needs to grapple. The challenge for lawmakers is clear. They must unlearn the ways in which defense spending has been determined in recent years, based on fuzzy strategies and bad-faith arguments by those who stand to benefit from a bloated defense budget, and relearn how to focus the spending on real security requirements and fixed goals.

Rising Defense Budget

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine in February, the U.S. defense budget had been trending upward at a greater rate than inflation or the risk climate would dictate. Last year’s bill to authorize defense-related spending and policies, the fiscal year 2022 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), increased the topline authorization level by $25 billion above President Joe Biden’s request, a request that was already billions more than the previous year. The initial votes to boost the defense budget took place months before Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered Russian forces into Ukraine and even before there was widespread concern in Washington that Russian troop buildups along Ukraine’s borders could lead to direct conflict. In fact, discretionary dollars allocated for national defense programs have increased by an average of $23 billion annually during the administrations of Biden and President Donald Trump.1 Since the end of World War II, the United States has spent proportionally more on the military than it does now only during the 2009 and 2010 spending peaks of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Proponents of higher defense spending argue that these historic levels of spending are justified, and in the eyes of some, they are still insufficient. The United States is operating in a new strategic environment, they say, one with two near-peer strategic rivals in Russia and China; enduring threats from North Korea, Iran, and proxy terrorist groups; and new, emerging technologies and war-fighting domains. To these worried minds, the solution is obvious: a strong military bolstered by a robust defense budget to address all these threats simultaneously.

The prioritization of a strong national defense understandably receives widespread support within Congress and among the voters who sent them there, but how should the country define exactly what constitutes a strong national defense? The easiest metric is seemingly the amount of money set aside for the military. After all, it seems logical that a well-funded defense budget will ensure that U.S. national security strategy objectives are met. In theory, it is the president’s duty to outline a cohesive national security strategy and translate it into a budget. Congress will then work to fulfill its constitutional duty to translate the budget into real dollars, ensuring that the U.S. military receives adequate funding without wasting taxpayer dollars or crowding out other nondefense national priorities.

In practice, however, the defense budget is often increased year after year without solid grounding in a defined, workable strategy. Although the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy, released in October, emphasizes “shared challenges” that necessitate cooperation across international borders, the dominate focus is to “outcompete” rival major powers, namely China and Russia.2 This latest catchphrase of “strategic competition” also had been central to the national security strategy outlined by the Trump administration, but most policymakers and experts in Washington would be hard-pressed to define what the term actually means or how competition can be a security end goal in itself. What the strategic competition mindset does provide is a magic word to ensure that any program, regardless of its future relevance or utility, will be funded if the request is categorized as necessary to compete against China or Russia. Yet, competing with China and Russia in every corner of the globe would be very expensive, requiring ever-larger investments in operations, maintenance, and the retention of legacy platforms that detract from opportunities to right-size the military for the future and seek noncompetitive methods of addressing shared threats such as nuclear proliferation and climate change.3

Compounding this dynamic is the outsized influence exerted on the budget process by the service branches, with their parochial concerns; defense contractors and other powerful lobbies; and lawmakers who have strong interests in serving their districts and play lead roles in developing and approving spending.4 The result is a failure to effectively translate an already opaque defense strategy into dollars, leaving the government with an “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to crafting the budget and a misguided notion that if enough money is thrown at a threat, it can be defeated.

Support for Ukraine

Unsurprisingly, many lawmakers immediately seized the opportunity following the Russian invasion to call for boosting the U.S. defense budget beyond existing high spending levels. On the same day that Russian tanks first rolled into the Donbas region of Ukraine, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) concluded his statement regarding the invasion with a pitch not only for shoring up Ukrainian and NATO defenses, but also for increasing the base U.S. defense budget. “We need to rebuild our atrophied ability to deter and defend against aggression by these adversaries. That means we must invest more robustly in our own military capabilities to keep pace,” he said.5 Similar statements from many other members of Congress from both sides of the aisle followed in the weeks and months after the invasion.

Understandably, Congress, in unison with the White House, has been eager to supply Ukraine and frontline NATO allies with the necessary weapons and support to defend themselves against unprovoked Russian aggression. To do so, the United States has provided historic levels of military aid to Ukraine in the months prior to and since the start of the war, mostly through emergency supplemental appropriations. In total, the United States has provided $28 billion in defense aid for Ukraine in fiscal year 2022.6 Specifically, these funds have been used to subsidize, train, equip, and advise Ukrainian forces through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative; to replenish stocks of U.S. equipment sent to Ukraine; and to fund Department of Defense operations and personnel accounts, including covering costs related to additional U.S. troop deployments to Europe.7

Although much of this money has flowed directly to the frontline, a significant chunk has gone to the Pentagon and to defense contractors to cover costs related to U.S military support for Ukrainian forces.8 The most recent supplemental defense funding approved by Congress in late September also included some longer-term and less war-related spending, including for research and development accounts and for bolstering the U.S. domestic defense industrial base. As more needs and expenses accrue down the line, Congress can be expected to continue providing additional emergency funding for Ukraine for the foreseeable future in a similar manner, although the quantity and type of weapons that the United States should be providing persists as a source of debate.

As a result, justifying increases to U.S. defense spending through the regular appropriations and authorization processes to cover Ukraine-related costs should be seen as disingenuous double-dipping into the pockets of taxpayers because the supplemental emergency funding is covering those costs. Topline increases in the base budget have little or nothing to do with shoring up Ukrainian forces or replenishing U.S. stocks. Rather, they are exploiting Russian aggression to beef up the U.S. military. To this end, many of those calling for increases in the annual defense budget in response to the war are making a direct link between Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and a supposed weakness in the U.S. defense budget.9

This claim is unfounded. By some estimates, the U.S. defense budget in 2021 accounted for 38 percent of the world’s total military expenditures and was 12 times greater than the share of Russian spending on its own military.10 Based on these figures alone, it is difficult to imagine how anyone could argue credibly that a more robustly funded U.S. military would have stopped Russia from invading Ukraine. Moreover, the embarrassingly bad performance of the Russian military has highlighted what most experts already knew: there is already a huge qualitative gap between Russia and the West.

The strength of the U.S. military was not a factor in Putin’s calculus to invade Ukraine earlier this year, however warped that calculus may have been. That Russia has been careful thus far not to escalate the conflict in a way that would provoke direct U.S. and NATO intervention, combined with Putin’s reckless overreliance on nuclear blackmailing, underscores the comparative weakness of Russian conventional forces.11 Instead of inflating the threat posed by Russia, U.S. policymakers should conclude from Russia’s war failures that the United States needs to fundamentally modify its defense strategy to take into account the factors that allowed Ukraine to resist Russian aggression successfully without excessive spending.

Budget Inflation in 2022

Predictably, this lesson was not reflected in recent budget developments on Capitol Hill. In the fiscal year 2023 NDAA that is now making its way through Congress, the House voted to boost the defense topline by $37 billion while the Senate added $45 billion beyond the White House request, which already was higher than previously projected.

The increases in this year’s defense policy bills were endorsed by bipartisan majorities during markups in the relevant committees and were explained largely as responses to the war in Ukraine and to offset historic inflation at home. “War. Inflation. That’s it.… That sets the tone for more, more, more for the military,” said Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), who chairs a House Armed Services subcommittee and opposed the increase.12

An examination into the specifics, however, shows that funding related to inflationary pressures and Ukraine only account for a fraction of the overall increases. The bulk of programs receiving funding boosts came directly off the “unfunded priorities lists” developed by certain segments of the Pentagon and National Nuclear Security Administration, just as was done in the previous fiscal year when the defense budget also was increased. These lists, commonly referenced as “wish lists” or “risk lists” depending on one’s perspective, are a budget gimmick. They allow the military service branches, combatant commands, and various defense-related agencies to circumvent top civilian leadership at the White House and Pentagon by directly providing Congress with a list of so-called priorities that did not make it into the administration’s budget request and can be used as an easy road map for boosting the budget.13

Although the House and Senate amendments to increase defense expenditures differed in some areas, funding has been authorized to procure additional ships and aircraft, sustain legacy weapons systems that the services are trying to retire, invest in unproven missile defense technologies, and fund R&D projects and infrastructure upgrades that were not deemed priorities in the administration’s budget request. The utility of many of these programs for countering Russian aggression in the current conflict is unclear, and their impact on offsetting inflationary pressures at the Pentagon is nil. In fact, this stunt is exactly what Pentagon leaders warned Congress against doing, as expressed by Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks in May: “What we don’t want is added topline [funding] that’s filled with new programs that we can’t support and afford in the out-years and that doesn’t cover inflation…. That is my number one concern.”14

Although the House and Senate have yet to negotiate a final NDAA and appropriations package for 2023, the national defense discretionary topline figure likely will total more than $850 billion, even before accounting for any additional emergency supplementals related to Ukraine. Many lawmakers will be tempted to look at this large figure and conclude that it meets the mark of responding to Russian aggression in Ukraine and domestic inflation, but more spending does not necessarily equal more security. In fact, the specifics of this year’s overall boost reveal a continuation of congressional bad habits to fund the Pentagon in a manner inconsistent with its own wishes and at the expense of taxpayers.15

The Nuclear Budget

One area of the defense budget that is likely to be singled out as requiring bigger investments following the invasion of Ukraine is the nuclear weapons portfolio. Although Russia’s lagging conventional capabilities have been on full display in the war, so has its use of nuclear saber-rattling to project strength and deter outside intervention on Ukraine’s behalf. Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons are cause for concern in themselves, but they also have provided fodder to nuclear hawks who would like to see the U.S. nuclear arsenal grow in quantity and capabilities.

The total price tag for U.S. nuclear weapons sustainment and modernization plans could reach $1.5–2.0 trillion over 30 years. Although much of this spending already has been committed, there still are many opportunities to trim excess and avoid exacerbating a new arms race while maintaining a credible and reliable U.S. deterrent. Nevertheless, close watchers of the nuclear budget certainly will not be surprised if the total figure reaches the high end of the total estimate or increases even further.

The total price tag for U.S. nuclear weapons sustainment and modernization plans could reach $1.5–2.0 trillion over 30 years. Although much of this spending already has been committed, there still are many opportunities to trim excess and avoid exacerbating a new arms race while maintaining a credible and reliable U.S. deterrent. Nevertheless, close watchers of the nuclear budget certainly will not be surprised if the total figure reaches the high end of the total estimate or increases even further.

Many of the modernization plans already have faced or are likely to face schedule delays and cost increases beyond their initial projections. For example, the U.S. Government Accountability Office reported this summer that the estimated total acquisition costs for the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program have grown by more than $3.4 billion since the congressional watchdog’s last annual assessment.16 Similarly, the Air Force’s total cost estimate for the long-range standoff weapons system, a new air-launched cruise missile being developed by Raytheon Technologies under a sole-source contract, has already ballooned by $5.4 billion, an increase of 50 percent from the service’s original estimate in 2016.17 The new cruise missile’s associated warhead, the W80-4, has been plagued by delays that could risk cost increases down the line.18

Spending on nuclear programs is likely to see a further uptick if the long-standing push to develop new U.S. nuclear weapons gains fresh momentum from Putin’s nuclear threats. This trend was already in process with the development and deployment of the W76-2 low-yield submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead that was added to existing modernization plans by the Trump administration. Despite Biden’s previous opposition to the weapon, his administration gave its endorsement to retaining the W76-2 warhead in the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, deeming the geopolitical landscape too hostile to remove the warhead from U.S. submarines.

Moreover, the Biden administration’s sensible decision not to move forward with another Trump-era plan, for a new low-yield sea-launched cruise missile, was met with fierce criticism from Republicans. These lawmakers channeled comments from certain high-ranking military commanders who publicly disagreed with Biden’s decision, even though the Navy leadership itself opposed the program.19 This pressure led Democratic leaders of the House and Senate armed services subcommittees that authorize nuclear weapons spending to broker deals with their Republican counterparts to allow $45 million for R&D of the system to move forward in the 2023 defense authorization bill. Even such a relatively low level of funding for the missile and its associated warhead potentially could translate into full-scale development and production in coming years.

By the end of this decade, when modernization spending as now projected is set to peak, nuclear weapons could account for nearly 10 percent of total U.S. national defense spending.20 Nothing about the situation in Ukraine recommends such a course. If anything, Russia’s lack of military success, despite possessing the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, argues for less U.S. reliance on nuclear weapons for anything beyond deterrence. Instead of adding even more weapons and requirements to U.S. nuclear modernization plans, Congress needs to enforce greater oversight of the ballooning nuclear budget with the aim of keeping plans on schedule and on budget. To reduce nuclear escalation risks, the priority should be placed on negotiating with the Russians to ensure that the last remaining bilateral treaty regarding U.S. and Russian strategic arms, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, does not expire in 2026 without a plan to maintain its limitations and address additional areas of risk. History has proven that, even during periods of heightened dangers and tensions, the most sensible and urgent path forward requires difficult diplomacy.

The Path Forward

In recent years, there have been several efforts in Congress to interrupt the status quo budget process and rein in wasteful defense spending. The most visible one is the campaign, led primarily by progressive members of the House and Senate as part of the annual defense policy process, to implement a 10 percent cut in the defense budget that would be applied across the board, except for personnel and health programs. Other proposals have gained more traction, including amendments put forward on the floor to reverse just the increases added to the national defense budget topline in committee markups. Although these efforts all failed, they have provided important openings for an overdue debate on the trajectory of defense spending and the process that fuels it. More specifically, such initiatives have highlighted the inadvisability of simply mandating increases or decreases to the topline without solid strategic reasons.

Lawmakers in both parties and from across the political spectrum have put forth proposals to enact more targeted cuts in expensive and controversial military programs, such as the F-35 fighter jet and the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, and to allow for the retirement of costly, unwanted platforms such as the Littoral Combat Ship. Finally, there has been a steady drumbeat of proposals that seek to root out waste, fraud, and abuse in the Pentagon and increase oversight of defense dollars. Specific proposals in this category include repealing the statutory requirements for unfunded priorities lists, imposing more penalties on the Pentagon until it passes a financial audit, and reforming acquisition laws to prevent private contractors from engaging in price gouging.

Lawmakers in both parties and from across the political spectrum have put forth proposals to enact more targeted cuts in expensive and controversial military programs, such as the F-35 fighter jet and the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, and to allow for the retirement of costly, unwanted platforms such as the Littoral Combat Ship. Finally, there has been a steady drumbeat of proposals that seek to root out waste, fraud, and abuse in the Pentagon and increase oversight of defense dollars. Specific proposals in this category include repealing the statutory requirements for unfunded priorities lists, imposing more penalties on the Pentagon until it passes a financial audit, and reforming acquisition laws to prevent private contractors from engaging in price gouging.

In sum, Congress does not lack proposals for scaling back bloat in the defense budget and making the Pentagon a more fiscally responsible and effective entity, all of which would enhance U.S. national security. Unfortunately, the majority of lawmakers do not appear keen to enact overdue reforms or harden their oversight of the Pentagon. These critical failings are likely to be exacerbated by hawkish lawmakers who will continue to point to Putin’s war on Ukraine, despite evidence of the Russian military’s serious shortcomings, as an easy excuse for pouring more money into every Pentagon account, including programs that do little to bolster U.S. national security.

This approach makes Americans less safe. Through blank checks and hyperfixation on competition, the defense budget overextends the military and allows for fiscal mismanagement at the Pentagon at the expense of readiness and efficiency. The current approach also provides little room to adequately address nontraditional threats such as climate change and pandemics, as well as the cooperative solutions needed across the U.S. government and with allies and adversaries to address them. This moment calls for a long overdue examination of how to spend smarter and center a defined, achievable strategy in U.S. budgetary decisions, not the other way around.

ENDNOTES

1. Stephen Semler, “Reagan’s Military Buildup vs. Pentagon Spending in the Trump-Biden Era,” Speaking Security Newsletter, No. 166, August 2, 2022, https://stephensemler.substack.com/p/reagans-military-buildup-vs-pentagon.

2. The White House, “National Security Strategy,” October 2022, pp. 11–12, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

3. Cornell Overfield, “Biden’s ‘Strategic Competition’ Is a Step Back,” Foreign Policy, October 13, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/13/biden-strategic-competition-national-defense-strategy/; Becca Wasser and Stacie Pettyjohn, “Why the Pentagon Should Abandon ‘Strategic Competition,’” Foreign Policy, October 19, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/19/2022-us-nds-national-defense-strategy-strategic-competition/.

4. Julia Gledhill and William D. Hartung, “Spending Unlimited,” TomDispatch, September 11, 2022, https://tomdispatch.com/spending-unlimited/.

5. Office of Senator Mitch McConnell, “McConnell on Putin Invading Ukraine: ‘The World Is Watching’ for America’s Response,” press release, February 22, 2022, https://www.mcconnell.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/pressreleases?ID=50ACBABF-06BF-4B40-A463-1687FA07D542.

6. Additional humanitarian funding has been provided from other nondefense accounts, so the $28 billion figure only represents programs under the purview of the Department of Defense.

7. For more on the specifics of the $28 billion provided in Defense Department funds to Ukraine so far, see Christina L. Arabia, Andrew S. Bowen, and Cory Welt, “U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine,” Congressional Research Service in Focus, IF12040, August 29, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12040.

8. Steve Ellis, “Surprise: Today’s ‘Must Pass’ CR Bill Includes Defense Company Goodies,” Responsible Statecraft, September 30, 2022, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2022/09/30/surprise-todays-must-pass-cr-bill-includes-defense-company-goodies/.

9. See Kori Schake, “American Must Spend More on Defense,” Foreign Affairs, April 5, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2022-04-05/america-must-spend-more-defense; Elbridge A. Colby, “More Spending Alone Won’t Fix the Pentagon’s Biggest Problem,” Time, March 28, 2022, https://time.com/6161573/us-defense-budget-strategy/.

10. Diego Lopes Da Silva et al., “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2021,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2022, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/fs_2204_milex_2021_0.pdf.

11. For a deeper discussion on these points, see Lyle J. Goldstein, “Threat Inflation, Russian Military Weakness, and the Resulting Nuclear Paradox: Implications of the War in Ukraine for U.S. Military Spending,” Costs of War Project, September 15, 2022, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/Threat%20Inflation%20and%20Russian%20Military%20Weakness_Goldstein_CostsofWar-2.pdf.

12. Connor O’Brien, “‘There Was Almost No Debate’: How Dems’ Defense Spending Spree Went From Shocker to Snoozer,” Politico, July 26, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/26/democrats-defense-spending-military-00048041.

13. For more on the history of and possible future for wish lists, see Andrew Lautz, “Congress Should Do Away With DoD Unfunded Priorities Lists, A Multibillion-Dollar Wish List Boondoggle,” National Taxpayers Union Issue Brief, March 31, 2021, https://www.ntu.org/library/doclib/2021/03/Congress-Should-Do-Away-With-DoD-Unfunded-Priorities-Lists-A-Multibillion-Dollar-Wish-List-Boondoggle.pdf.

14. Andrew Clevenger, “Pentagon to Work With Congress to Mitigate Inflation’s Budget Bite,” Roll Call, May 6, 2022, https://rollcall.com/2022/05/06/pentagon-to-work-with-congress-to-mitigate-inflations-budget-bite/.

15. For more information, see Ben Freeman and William Hartung, “Spending More and More for Less and Less at the Pentagon,” The Hill, April 15, 2022, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/3269553-spending-more-and-more-for-less-and-less-at-the-pentagon/.

16. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: Challenges to Fielding Capabilities Faster Persist,” GAO-22-105230, June 2022, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105230.pdf.

17. Kingston Reif, “New Cruise Missile Cost Rises,” Arms Control Today, September 2021, pp. 32–33.

18. Dan Leone, “Two-Year Delay for First W80-4 Warhead, but NNSA Says Will Still Deliver On-time to Air Force,” Nuclear Security & Deterrence Monitor, Vol. 26, No. 31 (August 4, 2022), https://www.exchangemonitor.com/two-year-delay-for-first-w80-4-warhead-but-nnsa-says-will-still-deliver-on-time-to-air-force-2/?printmode=1.

19. Shannon Bugos, “U.S. Defense Officials Balk at Biden’s Nuclear Budget,” Arms Control Today, June 2022, pp. 30–32.

20. Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos, “Biden’s Disappointing First Nuclear Weapons Budget,” Arms Control Association Issue Brief, Vol. 13, No. 4 (July 9, 2021), https://www.armscontrol.org/issue-briefs/2021-07/bidens-disappointing-first-nuclear-weapons-budget.

Monica Montgomery is a policy analyst at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation focusing on issues involving nuclear arms control, nonproliferation, and the U.S. defense budget.

Today, tensions that once again could lead the United States into direct conflict with Russia, as well as China, are growing. As Russian President Vladimir Putin doubles down on his disastrous decision to invade Ukraine and issues dangerous threats to use nuclear weapons, the risk of nuclear war is probably higher than at any point since 1962. The invasion has also led to the suspension of the U.S.-Russian strategic stability dialogue and talks designed to maintain limits on their strategic nuclear arsenals.

Today, tensions that once again could lead the United States into direct conflict with Russia, as well as China, are growing. As Russian President Vladimir Putin doubles down on his disastrous decision to invade Ukraine and issues dangerous threats to use nuclear weapons, the risk of nuclear war is probably higher than at any point since 1962. The invasion has also led to the suspension of the U.S.-Russian strategic stability dialogue and talks designed to maintain limits on their strategic nuclear arsenals.

The areas of defense spending that need reevaluating in this new environment raise major questions with which Washington urgently needs to grapple. The challenge for lawmakers is clear. They must unlearn the ways in which defense spending has been determined in recent years, based on fuzzy strategies and bad-faith arguments by those who stand to benefit from a bloated defense budget, and relearn how to focus the spending on real security requirements and fixed goals.

The areas of defense spending that need reevaluating in this new environment raise major questions with which Washington urgently needs to grapple. The challenge for lawmakers is clear. They must unlearn the ways in which defense spending has been determined in recent years, based on fuzzy strategies and bad-faith arguments by those who stand to benefit from a bloated defense budget, and relearn how to focus the spending on real security requirements and fixed goals. The total price tag for U.S. nuclear weapons sustainment and modernization plans could reach $1.5–2.0 trillion over 30 years. Although much of this spending already has been committed, there still are many opportunities to trim excess and avoid exacerbating a new arms race while maintaining a credible and reliable U.S. deterrent. Nevertheless, close watchers of the nuclear budget certainly will not be surprised if the total figure reaches the high end of the total estimate or increases even further.

The total price tag for U.S. nuclear weapons sustainment and modernization plans could reach $1.5–2.0 trillion over 30 years. Although much of this spending already has been committed, there still are many opportunities to trim excess and avoid exacerbating a new arms race while maintaining a credible and reliable U.S. deterrent. Nevertheless, close watchers of the nuclear budget certainly will not be surprised if the total figure reaches the high end of the total estimate or increases even further. Lawmakers in both parties and from across the political spectrum have put forth proposals to enact more targeted cuts in expensive and controversial military programs, such as the F-35 fighter jet and the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, and to allow for the retirement of costly, unwanted platforms such as the Littoral Combat Ship. Finally, there has been a steady drumbeat of proposals that seek to root out waste, fraud, and abuse in the Pentagon and increase oversight of defense dollars. Specific proposals in this category include repealing the statutory requirements for unfunded priorities lists, imposing more penalties on the Pentagon until it passes a financial audit, and reforming acquisition laws to prevent private contractors from engaging in price gouging.

Lawmakers in both parties and from across the political spectrum have put forth proposals to enact more targeted cuts in expensive and controversial military programs, such as the F-35 fighter jet and the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, and to allow for the retirement of costly, unwanted platforms such as the Littoral Combat Ship. Finally, there has been a steady drumbeat of proposals that seek to root out waste, fraud, and abuse in the Pentagon and increase oversight of defense dollars. Specific proposals in this category include repealing the statutory requirements for unfunded priorities lists, imposing more penalties on the Pentagon until it passes a financial audit, and reforming acquisition laws to prevent private contractors from engaging in price gouging. Although news reports and press releases provide the public with information on some orders and deliveries of conventional arms, fewer states are publicly reporting on their arms transfers compared to 10 or 20 years ago. If not for reporting by the world’s largest exporters of conventional arms on their activities, multilateral instruments designed to provide transparency on international arms transfers would be almost worthless. All of this raises the questions of what happened to the promise of those multilateral instruments, the UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) and the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and what can be done to reverse the decline in reporting on arms exports and imports.

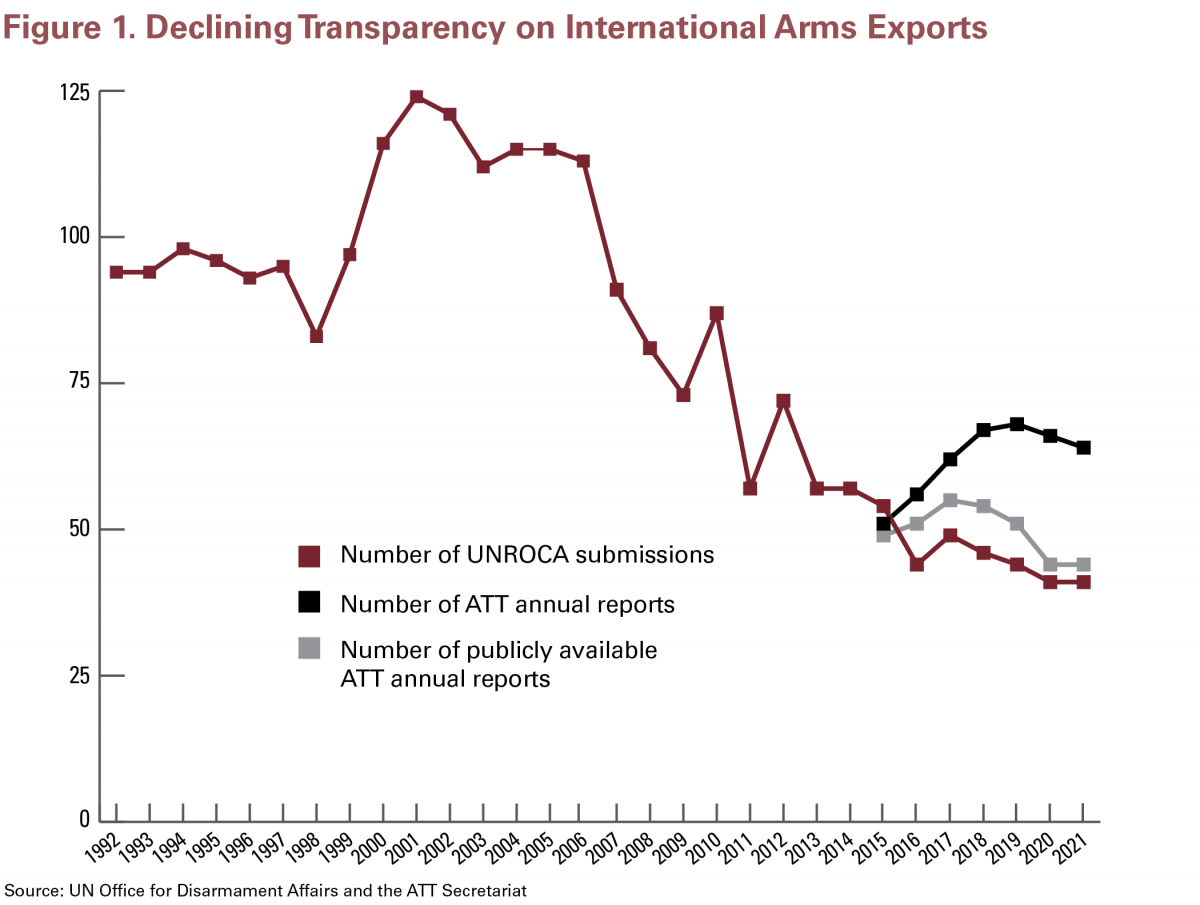

Although news reports and press releases provide the public with information on some orders and deliveries of conventional arms, fewer states are publicly reporting on their arms transfers compared to 10 or 20 years ago. If not for reporting by the world’s largest exporters of conventional arms on their activities, multilateral instruments designed to provide transparency on international arms transfers would be almost worthless. All of this raises the questions of what happened to the promise of those multilateral instruments, the UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) and the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and what can be done to reverse the decline in reporting on arms exports and imports. UNROCA reporting levels logically might be expected to exceed those for the ATT because all UN member states are called on to participate in the register, whereas just more than half of these states are obliged to report on international arms transfers to the ATT Secretariat. Yet, almost from the start, ATT annual reporting rates have been higher than those for the register. Whereas all submissions to the UNROCA are available publicly, ATT states-parties can opt for their annual reports to be made available only to other ATT states-parties. In the first year of ATT reporting, two reports were made available for ATT states-parties only, while the other 52 reports were publicly available. By contrast, of the 64 ATT states-parties that submitted their annual report for 2021 by October 12, 2022, 20 states (31 percent) had chosen not to make their report publicly available.

UNROCA reporting levels logically might be expected to exceed those for the ATT because all UN member states are called on to participate in the register, whereas just more than half of these states are obliged to report on international arms transfers to the ATT Secretariat. Yet, almost from the start, ATT annual reporting rates have been higher than those for the register. Whereas all submissions to the UNROCA are available publicly, ATT states-parties can opt for their annual reports to be made available only to other ATT states-parties. In the first year of ATT reporting, two reports were made available for ATT states-parties only, while the other 52 reports were publicly available. By contrast, of the 64 ATT states-parties that submitted their annual report for 2021 by October 12, 2022, 20 states (31 percent) had chosen not to make their report publicly available. The war gave fresh urgency to the new international political declaration on the use of explosive weapons in populated areas that was agreed in June and will open for endorsement at a conference in Dublin on Nov. 18. The declaration recognizes the devastating harm to civilians from bombing and shelling in towns and cities and commits signatory states to impose limits on the use of these weapons and take action to address harm to civilians. States that sign the document commit to develop or improve practices to protect civilians during conflict, collect and share data, and provide victim assistance.

The war gave fresh urgency to the new international political declaration on the use of explosive weapons in populated areas that was agreed in June and will open for endorsement at a conference in Dublin on Nov. 18. The declaration recognizes the devastating harm to civilians from bombing and shelling in towns and cities and commits signatory states to impose limits on the use of these weapons and take action to address harm to civilians. States that sign the document commit to develop or improve practices to protect civilians during conflict, collect and share data, and provide victim assistance. It is not just that we’ve agreed that countries need to “ensure that our armed forces adopt and implement a range of policies and practices to help avoid civilian harm, including by restricting or refraining as appropriate the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, when their use may be expected to cause harm to civilians or civilian objects.” We’ve also got agreement on just what that harm is and how wide-ranging the harm is, not just in terms of deaths and injuries but also in terms of civilian infrastructure, food systems, health systems, and long-term development.

It is not just that we’ve agreed that countries need to “ensure that our armed forces adopt and implement a range of policies and practices to help avoid civilian harm, including by restricting or refraining as appropriate the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, when their use may be expected to cause harm to civilians or civilian objects.” We’ve also got agreement on just what that harm is and how wide-ranging the harm is, not just in terms of deaths and injuries but also in terms of civilian infrastructure, food systems, health systems, and long-term development. ACT: Since the declaration was agreed in June, you have moved on to a new position as director of Ireland’s development agency, Irish Aid. Is there a connection between those two roles?

ACT: Since the declaration was agreed in June, you have moved on to a new position as director of Ireland’s development agency, Irish Aid. Is there a connection between those two roles? The Evolution of a Nonproliferation Icon

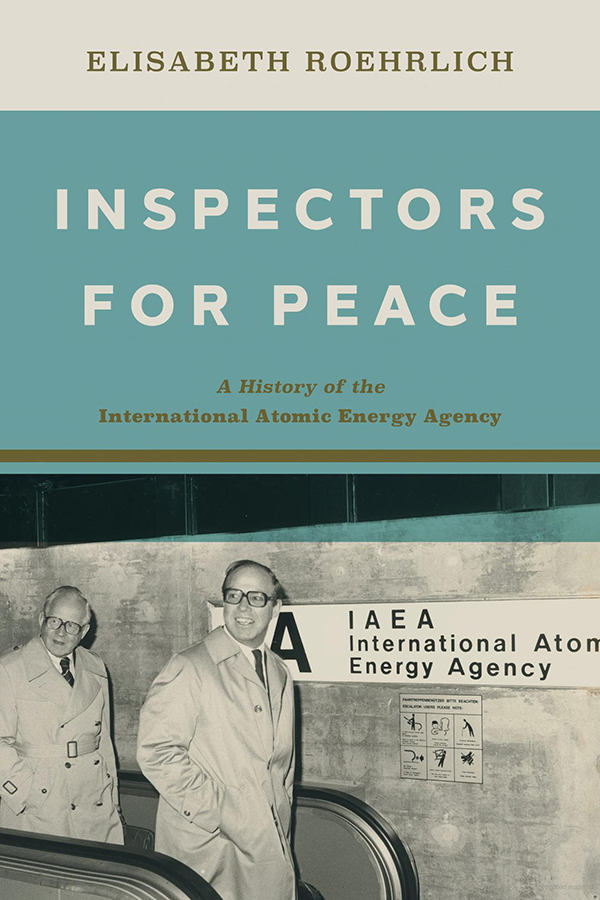

The Evolution of a Nonproliferation Icon Although many themes and events in the book, such as the role safeguards played in negotiations over the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and the IAEA response to Chernobyl, are well documented in other works, Roehrlich’s access to IAEA archival materials that were only made available after 2016 and extensive interviews offer unique insights and perspectives into the agency’s work. Her decision to begin the narrative prior to the agency’s establishment also rewards the reader with a more detailed understanding of how great-power thinking about proliferation threats and the means to prevent further nuclear-armed states evolved from the end of World War II, particularly for the United States. This early history provides a critical backdrop for understanding why IAEA safeguards were initially so weak and were applied only to select nuclear facilities in a few states.

Although many themes and events in the book, such as the role safeguards played in negotiations over the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and the IAEA response to Chernobyl, are well documented in other works, Roehrlich’s access to IAEA archival materials that were only made available after 2016 and extensive interviews offer unique insights and perspectives into the agency’s work. Her decision to begin the narrative prior to the agency’s establishment also rewards the reader with a more detailed understanding of how great-power thinking about proliferation threats and the means to prevent further nuclear-armed states evolved from the end of World War II, particularly for the United States. This early history provides a critical backdrop for understanding why IAEA safeguards were initially so weak and were applied only to select nuclear facilities in a few states. The strength of this past cooperation raises the question as to whether tensions between Russia and the United States over contemporary crises, such as Iran and North Korea, are an aberration or mark a new era when geopolitics trumps shared nonproliferation priorities.

The strength of this past cooperation raises the question as to whether tensions between Russia and the United States over contemporary crises, such as Iran and North Korea, are an aberration or mark a new era when geopolitics trumps shared nonproliferation priorities. Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb

Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb Transforming Nuclear Safeguards Culture: The IAEA, Iraq, and the Future of Non-Proliferation

Transforming Nuclear Safeguards Culture: The IAEA, Iraq, and the Future of Non-Proliferation Last summer, Iran began delivering drones that loiter, then explode on impact with a target, for Russian use in Ukraine, according to U.S. officials.

Last summer, Iran began delivering drones that loiter, then explode on impact with a target, for Russian use in Ukraine, according to U.S. officials. In an Oct. 10 report, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) noted that Iran informed the agency of its plans to install an additional three cascades of IR-2 centrifuges, which are used to enrich uranium. The report also confirmed that Iran had completed the installation of six cascades of IR-2 centrifuges and one cascade of IR-4 centrifuges since the last IAEA report was issued on Sept. 7. The IR-2 and IR-4 centrifuges enrich uranium more efficiently than Iran’s IR-1 model, which Tehran is limited to using to produce enriched uranium under the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), until 2026.

In an Oct. 10 report, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) noted that Iran informed the agency of its plans to install an additional three cascades of IR-2 centrifuges, which are used to enrich uranium. The report also confirmed that Iran had completed the installation of six cascades of IR-2 centrifuges and one cascade of IR-4 centrifuges since the last IAEA report was issued on Sept. 7. The IR-2 and IR-4 centrifuges enrich uranium more efficiently than Iran’s IR-1 model, which Tehran is limited to using to produce enriched uranium under the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), until 2026. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg on Oct. 11 rejected the prospect of canceling the “routine training” of Steadfast Noon, saying doing so would send “a very wrong signal.”

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg on Oct. 11 rejected the prospect of canceling the “routine training” of Steadfast Noon, saying doing so would send “a very wrong signal.” In an Oct. 11 press release, the IAEA said that Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi, who visited Kyiv on Oct. 6 and St. Petersburg on Oct. 11, engaged in “intense consultations” with Ukraine and Russia over establishing the protection zone and emphasizing the urgency of the situation. The agency did not indicate what barriers remain to reaching an agreement, but Grossi was quoted as saying, “We can’t waste any more time.”

In an Oct. 11 press release, the IAEA said that Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi, who visited Kyiv on Oct. 6 and St. Petersburg on Oct. 11, engaged in “intense consultations” with Ukraine and Russia over establishing the protection zone and emphasizing the urgency of the situation. The agency did not indicate what barriers remain to reaching an agreement, but Grossi was quoted as saying, “We can’t waste any more time.” Although Russia attacked the nuclear power plant in March and has occupied it since then in violation of international law, Ukrainian personnel have continued to operate the plant under significant duress. After the Ukrainian head of the Zaporizhzhia team, Igor Murashov, was kidnapped by the Russians in early October and held before being released, Kotin said the plant’s operations would be directed from Energoatom’s central offices. Grossi said Murashov’s absence had an “immediate and serious impact on decision-making in ensuring the safety and security of the plant.”

Although Russia attacked the nuclear power plant in March and has occupied it since then in violation of international law, Ukrainian personnel have continued to operate the plant under significant duress. After the Ukrainian head of the Zaporizhzhia team, Igor Murashov, was kidnapped by the Russians in early October and held before being released, Kotin said the plant’s operations would be directed from Energoatom’s central offices. Grossi said Murashov’s absence had an “immediate and serious impact on decision-making in ensuring the safety and security of the plant.”