November 2023

By Kenneth C. Brill

There is no shortage of reasons to be pessimistic about the future of nuclear arms control.

Relations among the major nuclear powers have soured. Russian President Vladimir Putin has made veiled nuclear threats related to Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine and stopped Russia’s implementation of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. China plans to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile and has rejected U.S. efforts to engage on strategic nuclear issues.1 In the United States, a rising chorus argues that nuclear arms control is over and that the U.S. nuclear stockpile should be increased, not just modernized.2 Meanwhile, states such as India, North Korea, and Pakistan are increasing their nuclear stockpiles.3

Relations among the major nuclear powers have soured. Russian President Vladimir Putin has made veiled nuclear threats related to Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine and stopped Russia’s implementation of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. China plans to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile and has rejected U.S. efforts to engage on strategic nuclear issues.1 In the United States, a rising chorus argues that nuclear arms control is over and that the U.S. nuclear stockpile should be increased, not just modernized.2 Meanwhile, states such as India, North Korea, and Pakistan are increasing their nuclear stockpiles.3

Nonetheless, another increasingly evident global threat provides compelling reasons for nuclear-armed nations to assess that a renewed push for nuclear arms control is very much in their long-term security interests. That threat is the impact of climate change on the natural world. The increasing number, intensity, and variety of natural disasters across the globe in recent years have demonstrated the growing danger to all states, whether nuclear armed or not. The cascading impacts of climate change on the natural world are no longer simply a concern of environmentalists or insurance companies; they are becoming a national and global security challenge that will intensify for decades to come. Dealing with this new threat to prosperity and stability will require developing an international strategic balance that recognizes that weapons of war are not the best defense against what will be the most sustained threats of the 21st century and beyond.

Reviving arms control diplomacy will be essential to achieving this new strategic balance. The goals of that diplomacy would be to rebuild or, in some cases, establish confidence among nuclear-armed states; reinforce constructive existing nuclear norms; sharply reduce the number of nuclear weapons; and free up resources to deal with the national and global consequences of climate change.

Facing a Common Threat

Nuclear arms control diplomacy was invented at the height of the Cold War when distrust between nuclear powers was deep, communications limited, and the threat of conflict a daily reality. Every U.S. president from Dwight Eisenhower until Donald Trump undertook diplomatic initiatives that produced arms control agreements. As a result, the combined U.S. and Russian stockpiles were reduced from some 60,000 weapons in the mid-1980s to a little more than 12,000 in 2020.4 In addition, constructive new norms—no use of nuclear weapons on the battlefield and no nuclear weapons testing—were established and are still holding.5

Despite the contentious post-cold war geopolitical situation, arms control diplomacy succeeded because the parties involved had shared interests. That perception of shared interest seems elusive now, given stepped up Chinese-U.S. competition over shaping the international order, Putin’s break with the West, and India’s ongoing strains with Pakistan and China. Even so, every nuclear- and non-nuclear-weapon state faces a common threat in the coming decades and beyond, namely the cascading impacts of climate change on the natural world within and outside their borders. That common threat is an opportunity for developing common ground on arms control.

Money for Nothing…or for Something?

Nuclear weapons are expensive to build, maintain, and modernize. According to one estimate, in 2021 the world’s nine nuclear-weapon states spent $82.4 billion on their nuclear weapons programs, with the United States investing the most, followed by China and Russia.6 The estimated cost for the U.S. nuclear stockpile modernization program over its planned 30-year life span is $1.5 trillion.7

In January 2022, China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States issued a statement reiterating what U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev vowed in 1985, that a nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought. They also committed to the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all.8 Assuming that those commitments are serious, vast sums of money are being spent on weapons that none of the nuclear-weapon states expects to use, even as they insist that possessing nuclear weapons is necessary in today’s geopolitical environment. Climate change, however, will upset the notion of what constitutes the most pressing national threats.

High temperatures, droughts, and intense rain events that produce inland flooding of arable land will reduce food production and increase food prices. Rising sea levels, more intense storms, and associated flooding will destroy coastal infrastructure, undermining the capacity of coastal cities to support their populations. Cities and infrastructure in many countries also will be affected by intense storms that result in inland flooding. High temperatures and droughts will reduce the national GDP of many states and make some areas unable to support current populations.9

The World Bank reports that these factors could force some 216 million people to be displaced within their own countries by 2050, with internal displacement “hotspots” occurring as early as 2030.10 A European think tank foresees an even more dire situation, estimating that some 1 billion people could be displaced by 2050 due to climate change, conflict, and civil unrest. Some, possibly many, of those internally displaced people subsequently will seek to migrate to other countries.11 A White House study assessed that climate-related migration has potentially significant negative implications for international security, instability, conflict, and geopolitics.12

Dealing with climate change will be expensive. A 2018 report assessed the then net present value of projected damages globally by 2100 from an increase in global temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius at $54 trillion or $69 trillion from an increase of 2.0 degrees.13 Meanwhile, Swiss Re, a leading global reinsurer, estimates that if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced quickly, climate change is likely to cut total global economic output by some 11-14 percent, or up to $23 trillion.14 The International Energy Agency estimates it will cost $5 trillion in annual new energy investments by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement goal of holding the increase in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius.15 The UN Environment Programme estimates that climate change adaptation costs faced by developing countries alone will be $140-300 billion annually by 2030 and $280-500 billion by 2050.

Climate change will not just hurt developing countries; nuclear-weapon states also will feel the pain. For example, Swiss Re assesses that China’s economy has the highest climate risk of any major economy, noting that its GDP could be reduced by as much as 6.6 percent by 2048 even if global temperatures increase only 1.5 degrees Celsius or by 18 percent if they rise by 2.6 degrees Celsius.16 The World Bank agrees, noting the vulnerability of China’s coastal cities, such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, to rising sea levels and its agricultural regions to drought.17 Among other nuclear-armed states, the U.S. intelligence community assesses India, North Korea, and Pakistan to be highly vulnerable to the cascading impacts of climate change.18

Climate change has economic and financial effects on the United States as well. Weather and climate disasters from 2016 to 2022 cost the country more than $1 trillion in storm and related damages, and 2023 already has set a record for the number of U.S. natural disasters producing more than $1 billion in costs.19 More broadly, a 2018 study estimated that U.S. GDP could be cut 10 percent by 2100 with a business-as-usual approach to climate change.20 Meanwhile, the White House reports that a failure to act on climate change could reduce revenue to the U.S. Department of the Treasury by $2 trillion per year, even as demands for climate-related expenditures, such as disaster relief and crop insurance payments, increase.21

Developed nations will be under increasing pressure to financially support developing countries in dealing with the effects of climate change. The need in developed countries to reduce transnational climate migration from developing countries will be a major incentive to do so. The growing political, economic, and humanitarian ramifications of climate change-related transnational migration are already evident, for example, along the southern U.S. border, in the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean to Europe, and in the movement of Bangladeshis into India. If not addressed, this climate-related flow of human misery only will increase and become more unsettling in the coming decades.

A Forever Timescale

The fiscal consequences of climate change not only will be substantial for developed and developing nations, they also will be enduring. Emitted carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for 300 to 1,000 years.22 Dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions and then dealing with the impact of these emissions on the natural world, including by removing them from the atmosphere, will therefore be the work of and fiscal burden on many generations. This means climate change-related expenditures and economic costs will become a substantial factor for most countries essentially in perpetuity.

Geopolitics inevitably will be affected by climate changes. Polar melting will create opportunities for jockeying among polar nations and others over new sea-lanes and some newly exposed territory, but that is more likely to be transitory than world changing. What comprises national power in a time of a transforming natural world, however, is likely to be different than what it was earlier. In today’s geopolitics, nuclear weapons represent power and status. Proponents of nuclear weapons cite their value in deterring attacks from other nations. Yet, nuclear weapons will not deter the growing threats to national stability and power from sea level rise, drought, or rising temperatures that reduce national economic output. They also will not deter the displacement of domestic populations or the stresses produced by transnational migration.

In the future, power is likely to accrue to states that successfully sustain their economies and national cohesion despite the pressures created by a mutating natural world. This will take considerable, sustained investments in climate change mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. These investments will dwarf what is being done today and will strain national climate-impaired fiscal capacities.

In the future, power is likely to accrue to states that successfully sustain their economies and national cohesion despite the pressures created by a mutating natural world. This will take considerable, sustained investments in climate change mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. These investments will dwarf what is being done today and will strain national climate-impaired fiscal capacities.

As a result, nuclear weapons increasingly will be neither a status symbol, nor relevant to the most urgent threats facing nuclear- and non-nuclear-weapon countries, but instead become an opportunity cost. That is, money spent on weapons that no one wants or has a plausible reason to use is money that cannot be used to address climate-related threats to national prosperity, stability, and security, which will be tangible and domestically urgent.

Mutually Assured Destruction or a Mutually Assured Future?

Despite fiscal pressures and growing political demands to address climate change-related challenges, particularly at home, no nuclear-armed state will unilaterally reduce its nuclear stockpile. Nuclear arms control diplomacy needs to be revived to help nuclear-armed nations and the global community as a whole transition from mutually assured destruction strategies to a strategic balance that addresses climate change impacts and promotes a mutually assured future.

Arms control diplomacy in a time of climate change must be different from the Cold War variety. Although the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention are global agreements, the bulk of the arms control instruments were negotiated on a bilateral basis between the Soviet Union/Russia and the United States. With the current roster of 10 nuclear- or near-nuclear-armed states, the time for bilateral arms control diplomacy is over.

Yet, the unsuccessful U.S. efforts to engage China in nuclear arms discussions and the failed multilateral efforts to persuade North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program demonstrate the challenges of moving beyond the Russian-U.S. construct of nuclear negotiations. One of the difficulties is that, despite sizeable reductions in the past, there is still a large gap between the Russian and U.S. nuclear stockpiles and everyone else. Another challenge is the deep distrust and tensions among most of the nuclear- or near-nuclear-armed states.

Reviving nuclear arms control and making it relevant for the climate change age will require leadership and creativity; it will also take time. Moscow and Washington took decades to reach significant bilateral nuclear arms control agreements. Negotiations involving even more nations with significantly different weapons programs will be even more complex and time consuming. Nonetheless, climate change impacts are growing; and a status quo approach will become increasingly untenable for nuclear-armed nations and others, so it is time to get started with thinking about how to advance arms control in a time of climate change.

Reviving nuclear arms control and making it relevant for the climate change age will require leadership and creativity; it will also take time. Moscow and Washington took decades to reach significant bilateral nuclear arms control agreements. Negotiations involving even more nations with significantly different weapons programs will be even more complex and time consuming. Nonetheless, climate change impacts are growing; and a status quo approach will become increasingly untenable for nuclear-armed nations and others, so it is time to get started with thinking about how to advance arms control in a time of climate change.

Despite its polarized domestic politics, strains with China and Russia, and recent quiescence on arms control, the United States is best placed to initiate new thinking and action on nuclear arms control. It has experience in developing and moving forward with nuclear-related initiatives, such as President Barack Obama’s nuclear security summits, and it is allied with or has constructive relations with five other nuclear-armed states (France, India, Israel, Pakistan, and the UK).

The first step in the diplomatic process would be for the United States to commit internally to pursuing nuclear arms control talks with other nuclear-weapon powers to reduce the threat of the use of nuclear weapons and allow greater focus on dealing sustainably with the impacts of climate change at home and elsewhere. Such an initiative would take years to develop and produce results, so bipartisan support would be essential, if challenging to obtain. Toward this end, the United States should explore the subject early on with its two NATO nuclear-weapon allies, France and the UK, with the goal of building a unified core to move the process forward procedurally and substantively.

Although negotiations eventually should focus on numbers of weapons, beginning with numbers would be unproductive, given existing tensions among various nuclear-armed states and the differences in their nuclear weapons programs. In his final book, the arms control scholar and practitioner Michael Krepon sensibly suggested that a multilateral arms control negotiation might gain traction by focusing on reinforcing three nuclear norms: no use of nuclear weapons in a conflict, no testing of nuclear weapons, and no proliferation of nuclear weapons to non-nuclear-armed states.23

The initial efforts at developing a multilateral nuclear arms control negotiation should focus on the eight most developed of the 10 nuclear-armed and near-nuclear-armed states, namely China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan, the UK, and the United States. Ideally, after gaining French and UK support, the United States would engage each of the remaining states on their concerns and ideas for advancing a process that would strengthen confidence among the nuclear-armed states and encourage collaboration on ensuring that nuclear weapons materials remain secure, despite the impacts of climate change.

If the initial U.S.-led bilateral consultations show promise, a meeting should be convened of the eight states consulted or some sub-group to explore how much further the process could go. Because the perception of U.S. leadership on this issue would be anathema to at least two nuclear-armed states, a neutral convener would be needed to arrange group meetings. The logical choice is the International Atomic Energy Agency, where all eight states are members. It could convene low-key meetings of the group and keep initial discussions informal and out of the limelight until all parties concur that there is something to be gained by this process. As the process proceeds, the states gain confidence with one another, and the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident, participants can expand their ambitions and move toward negotiating reduced numbers of nuclear weapons.

If the initial U.S.-led bilateral consultations show promise, a meeting should be convened of the eight states consulted or some sub-group to explore how much further the process could go. Because the perception of U.S. leadership on this issue would be anathema to at least two nuclear-armed states, a neutral convener would be needed to arrange group meetings. The logical choice is the International Atomic Energy Agency, where all eight states are members. It could convene low-key meetings of the group and keep initial discussions informal and out of the limelight until all parties concur that there is something to be gained by this process. As the process proceeds, the states gain confidence with one another, and the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident, participants can expand their ambitions and move toward negotiating reduced numbers of nuclear weapons.

Once there is engagement and positive momentum on making nuclear arms reductions among the eight, which could take years to achieve, it would be useful for some of the eight to reach out to North Korea and possibly to Iran to invite them into the process.

Problems Create Opportunities

Given the state of international affairs, particularly the ongoing violence in Ukraine and the renewed violence in the Middle East, the idea of a nuclear arms control initiative may sound absurd. Yet, a changing climate will alter the natural world dramatically and, in so doing, fundamentally change what counts as national and global security. This transforming world requires a new strategic balance between nuclear-armed nations, as well as between all nations and the natural world. Robust nuclear arms control diplomacy can help establish that new strategic balance between nations, significantly reduce or eliminate nuclear weapons, and free up resources needed to deal with the daunting financial challenges of restoring balance with the natural world.

The road to positive results for this new arms control diplomacy will be long and challenging, requiring unprecedented cooperation and collaboration between nations, as well as between those officials managing security issues and those dealing with climate-related issues. Although arms control diplomacy was useful in the 20th century, it is essential for the 21st century and beyond. It is time to get started on it.

ENDNOTES

1. Shannon Bugos, “Pentagon Sees Faster Chinese Nuclear Expansion,” Arms Control Today, December 2021, p. 26.

2. Bryant Harris, “U.S. Nuclear Commander Warns of Deterrence ‘Crisis’ Against Russia and China,” Defense News, May 4, 2022; Patty-Jane Geller, “U.S. Nuclear Weapons,” in 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2023), pp. 481-506, https://www.heritage.org/sites

/default/files/2022-10/2023_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength.pdf; Chris Gordon, “U.S. Should Consider Expanding Nuclear Arsenal to Cope With China and Russia, Study Says,” Air and Space Forces Magazine, March 31, 2023, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/us-consider-expanding-nuclear-arsenal-china-russia/.

3. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “States Invest in Nuclear Arsenals as Geopolitical Relations Deteriorate—New SIPRI Yearbook Out Now,” June 12, 2023, https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2023/states-invest-nuclear-arsenals-geopolitical-relations-deteriorate-new-sipri-yearbook-out-now.

4. “Historical Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles and Nuclear Tests by Country,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_nuclear_weapons_stockpiles_and_nuclear_tests_by_country (accessed October 18, 2023).

5. Michael Krepon, Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace: The Rise, Demise, and Revival of Arms Control (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021), p. 9.

6. Giulia Carbonara, “U.S. Nuclear Weapons Spending Compared to China and Russia,” Newsweek, June 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/us-nuclear-weapons-spending-compared-china-russia-1715542.

7. Kingston Reif, “The Trillion (and a Half) Dollar Triad?” Arms Control Association Issue Brief, Vol. 9, No. 6 (August 18, 2017), https://www.armscontrol.org/issue-briefs/2017-08/trillion-half-dollar-triad.

8. The European Leadership Network, “The Reagan-Gorbachev Statement: Background,” November 17, 2021, https://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/commentary/the-reagan-gorbachev-statement-background/; The White House, “Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” January 3, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements

-releases/2022/01/03/p5-statement-on-preventing-nuclear-war-and-avoiding-arms-races/.

9. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Summary for Policymakers,” 2018, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SPM_version_report_LR.pdf.

10. The World Bank, “Climate Change,” May 12, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/overview.

11. Institute for Economics & Peace, “Over One Billion People at Threat of Being Displaced by 2050 Due to Environmental Change, Conflict and Civil Unrest,” September 9, 2020, https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Ecological-Threat-Register-Press-Release-27.08-FINAL.pdf.

12. The White House, “Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration,” October 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Report-on-the-Impact-of-Climate-Change-on-Migration.pdf.

13. “Risks Associated With Global Warming of 1.5ºC or 2ºC, Tyndall Briefing Note, May 2018, https://tyndall.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/briefing_note_risks_warren_r1-1.pdf.

14. Christopher Flavelle, “Climate Change Could Cut World Economy by $23 Trillion in 2050, Insurance Giant Warns,” The New York Times, April 22, 2021.

15. International Energy Agency, “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector,” May 2021, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/7ebafc81-74ed-412b-9c60-5cc32c8396e4/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector-SummaryforPolicyMakers_CORR.pdf.

16. Swiss Re Institute, “The Economics of Climate Change,” April 22, 2021.

17. The World Bank, “China Country Climate and Development Report,” October 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/publication/china-country-climate-and-development-report; Dharisha Mirando et al., “CWR City Factsheets: At-a-Glance Coastal Threat Assessment for 20 APAC Cities,” November 2020, pp. 9-10, 25-26, https://www.chinawaterrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CWR_APACCT_20_Index_CityFactsheets.pdf.

18. U.S. National Intelligence Council, “National Intelligence Estimate: Climate Change and International Responses Increasing Challenges to US National Security Through 2040,” NIC-NIE-2021-10030-A, n.d., https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/NIE_Climate_Change_and_National_Security.pdf.

19. National Centers for Environmental Information, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Time Series,” October 23, 2023, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/time-series.

20. Caroline McMahan, “The Rising Costs of Global Warming,” Michigan Journal of Economics, March 13, 2021, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mje/2021/03/13/the-rising-costs-of-global-warming/.

21. Candace Vahlsing and Danny Yagan, “Quantifying Risks to the Federal Budget From Climate Change,” April 4, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2022/04/04/quantifying-risks-to-the-federal-budget-from-climate-change/.

22. Alan Buis, “The Atmosphere: Getting a Handle on Carbon Dioxide,” October 9, 2019, https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2915/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/.

23. Krepon, Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace, pp. 523-525.

Kenneth C. Brill is a former acting U.S. assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, a former U.S. ambassador to the International Atomic Energy Agency, and founding director of the U.S. National Counterproliferation Center.

Regrettably, the final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, released in October, suggests that, in response to Russia’s nuclear and military behavior and the anticipated growth of China’s nuclear arsenal, the U.S. arsenal “should be supplemented” to add more capability and flexibility to counter two “near-peer” nuclear adversaries. The bipartisan commission, which consists of 12 national security insiders, also advises that the United States “must be ready to deter and defeat” both adversaries in simultaneous wars, enhance its missile defense capabilities, and significantly bolster its nuclear weapons capabilities, including with new theater-range weapons.

Regrettably, the final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, released in October, suggests that, in response to Russia’s nuclear and military behavior and the anticipated growth of China’s nuclear arsenal, the U.S. arsenal “should be supplemented” to add more capability and flexibility to counter two “near-peer” nuclear adversaries. The bipartisan commission, which consists of 12 national security insiders, also advises that the United States “must be ready to deter and defeat” both adversaries in simultaneous wars, enhance its missile defense capabilities, and significantly bolster its nuclear weapons capabilities, including with new theater-range weapons.

Relations among the major nuclear powers have soured. Russian President Vladimir Putin has made veiled nuclear threats related to Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine and stopped Russia’s implementation of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. China plans to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile and has rejected U.S. efforts to engage on strategic nuclear issues.

Relations among the major nuclear powers have soured. Russian President Vladimir Putin has made veiled nuclear threats related to Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine and stopped Russia’s implementation of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. China plans to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile and has rejected U.S. efforts to engage on strategic nuclear issues. In the future, power is likely to accrue to states that successfully sustain their economies and national cohesion despite the pressures created by a mutating natural world. This will take considerable, sustained investments in climate change mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. These investments will dwarf what is being done today and will strain national climate-impaired fiscal capacities.

In the future, power is likely to accrue to states that successfully sustain their economies and national cohesion despite the pressures created by a mutating natural world. This will take considerable, sustained investments in climate change mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. These investments will dwarf what is being done today and will strain national climate-impaired fiscal capacities. Reviving nuclear arms control and making it relevant for the climate change age will require leadership and creativity; it will also take time. Moscow and Washington took decades to reach significant bilateral nuclear arms control agreements. Negotiations involving even more nations with significantly different weapons programs will be even more complex and time consuming. Nonetheless, climate change impacts are growing; and a status quo approach will become increasingly untenable for nuclear-armed nations and others, so it is time to get started with thinking about how to advance arms control in a time of climate change.

Reviving nuclear arms control and making it relevant for the climate change age will require leadership and creativity; it will also take time. Moscow and Washington took decades to reach significant bilateral nuclear arms control agreements. Negotiations involving even more nations with significantly different weapons programs will be even more complex and time consuming. Nonetheless, climate change impacts are growing; and a status quo approach will become increasingly untenable for nuclear-armed nations and others, so it is time to get started with thinking about how to advance arms control in a time of climate change. If the initial U.S.-led bilateral consultations show promise, a meeting should be convened of the eight states consulted or some sub-group to explore how much further the process could go. Because the perception of U.S. leadership on this issue would be anathema to at least two nuclear-armed states, a neutral convener would be needed to arrange group meetings. The logical choice is the International Atomic Energy Agency, where all eight states are members. It could convene low-key meetings of the group and keep initial discussions informal and out of the limelight until all parties concur that there is something to be gained by this process. As the process proceeds, the states gain confidence with one another, and the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident, participants can expand their ambitions and move toward negotiating reduced numbers of nuclear weapons.

If the initial U.S.-led bilateral consultations show promise, a meeting should be convened of the eight states consulted or some sub-group to explore how much further the process could go. Because the perception of U.S. leadership on this issue would be anathema to at least two nuclear-armed states, a neutral convener would be needed to arrange group meetings. The logical choice is the International Atomic Energy Agency, where all eight states are members. It could convene low-key meetings of the group and keep initial discussions informal and out of the limelight until all parties concur that there is something to be gained by this process. As the process proceeds, the states gain confidence with one another, and the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident, participants can expand their ambitions and move toward negotiating reduced numbers of nuclear weapons. Twenty-three years after Russia ratified the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Moscow is “unratifying” but not unsigning the pact as a by-product of its war on Ukraine and related tensions with the United States.

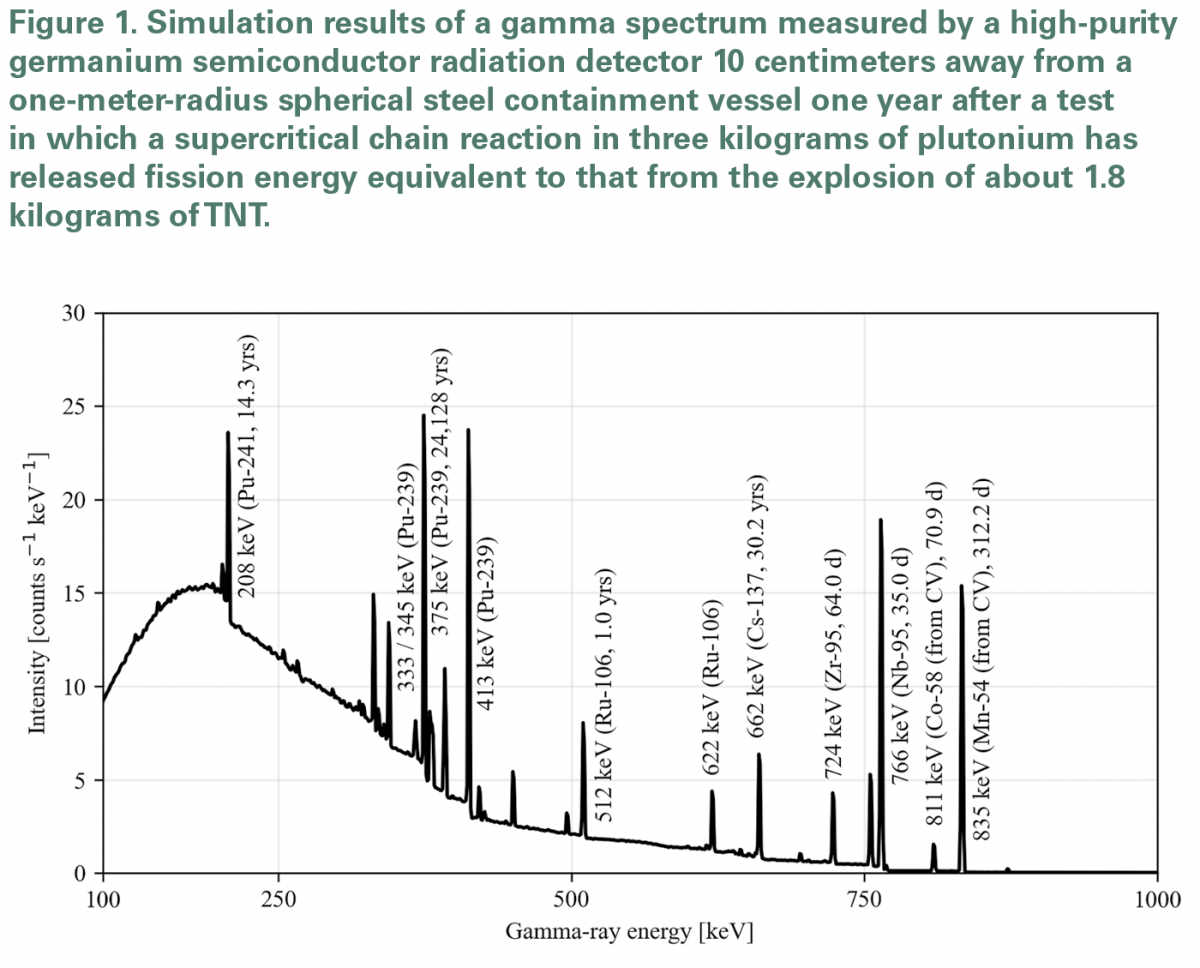

Twenty-three years after Russia ratified the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Moscow is “unratifying” but not unsigning the pact as a by-product of its war on Ukraine and related tensions with the United States. The U.S. government claims that China and Russia may be violating the U.S. interpretation of the treaty by carrying out supercritical tests in steel containment vessels underground. More than six decades ago, during the 1958-1961 test moratorium and the associated negotiations that ultimately produced the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the United States carried out very low-yield supercritical tests, which at that time were referenced as “hydronuclear” tests. The purpose of these experiments was to determine whether the fission “primaries” of some warheads recently added to the U.S. nuclear stockpile were “one-point safe.” A nuclear warhead is said to be one-point safe when no significant nuclear yield can be produced if the explosive around the plutonium pit is detonated at a single point by, for example, a bullet.

The U.S. government claims that China and Russia may be violating the U.S. interpretation of the treaty by carrying out supercritical tests in steel containment vessels underground. More than six decades ago, during the 1958-1961 test moratorium and the associated negotiations that ultimately produced the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the United States carried out very low-yield supercritical tests, which at that time were referenced as “hydronuclear” tests. The purpose of these experiments was to determine whether the fission “primaries” of some warheads recently added to the U.S. nuclear stockpile were “one-point safe.” A nuclear warhead is said to be one-point safe when no significant nuclear yield can be produced if the explosive around the plutonium pit is detonated at a single point by, for example, a bullet. Once the CTBT comes into force, any state-party may request a short-notice, on-site inspection of an area where it believes that a nuclear explosion or even a supercritical test may have taken place. Given that none of the remaining states that must sign and/or ratify the treaty have done so in recent years, however, the CTBT entry into force is years away. In the meantime, it would be advantageous to develop and demonstrate technical confidence-building measures through new methods and protocols that could determine whether contained experiments involving fissile material are subcritical.

Once the CTBT comes into force, any state-party may request a short-notice, on-site inspection of an area where it believes that a nuclear explosion or even a supercritical test may have taken place. Given that none of the remaining states that must sign and/or ratify the treaty have done so in recent years, however, the CTBT entry into force is years away. In the meantime, it would be advantageous to develop and demonstrate technical confidence-building measures through new methods and protocols that could determine whether contained experiments involving fissile material are subcritical.

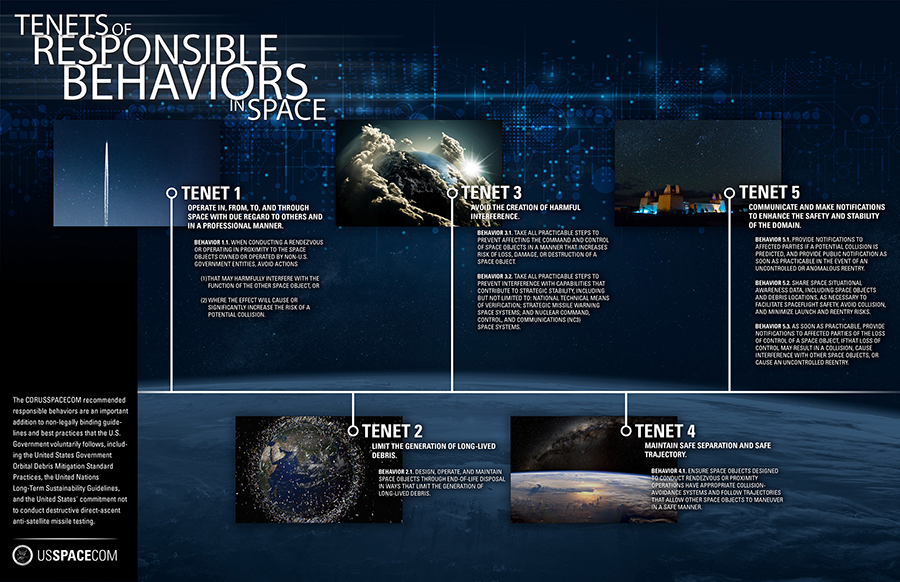

In fact, not even the title of a procedural report could be agreed. Arguably, this stems from a fundamental difference of philosophy on how space security should be governed internationally. Despite the overwhelming support for the report among states and civil society representatives in the working group, a handful of states abused the working group’s consensus rule and blocked the report. These states maintained a single-minded position that only legally binding instruments are meaningful. They refused to accept that the novel approach of cultivating a set of responsible behaviors to address the threats in, to, and from outer space enjoys wide backing from the international community, as evidenced by the fact that UN General Assembly Resolution 76/231, which established the working group, was adopted on a vote of 150-8.

In fact, not even the title of a procedural report could be agreed. Arguably, this stems from a fundamental difference of philosophy on how space security should be governed internationally. Despite the overwhelming support for the report among states and civil society representatives in the working group, a handful of states abused the working group’s consensus rule and blocked the report. These states maintained a single-minded position that only legally binding instruments are meaningful. They refused to accept that the novel approach of cultivating a set of responsible behaviors to address the threats in, to, and from outer space enjoys wide backing from the international community, as evidenced by the fact that UN General Assembly Resolution 76/231, which established the working group, was adopted on a vote of 150-8.

Even so, a handful of states maintain the position that there can be no other way but the legally binding way. Such an all-or-nothing approach is unrealistic in light of today’s international security and diplomatic realities. What is more concerning is that the technologically less developed and resourceful countries likely will bear the brunt of the damage and disadvantage arising from the vacuum of norms, rules, and principles because they will not be in position to protect their rare assets in space by themselves. As such, the handful of resistant states is preventing the international community from collectively safeguarding the world by addressing and mitigating current and future space-related threats. A few states have abused the rule of consensus to effectively veto anything that deviates from their own legally-binding instruments, including the title of the working group itself. What states ought to be engaging in is multilateral consensus-driven negotiations to reach agreements on vital issues of common interest, thus guaranteeing the peace and predictable governance of outer space.

Even so, a handful of states maintain the position that there can be no other way but the legally binding way. Such an all-or-nothing approach is unrealistic in light of today’s international security and diplomatic realities. What is more concerning is that the technologically less developed and resourceful countries likely will bear the brunt of the damage and disadvantage arising from the vacuum of norms, rules, and principles because they will not be in position to protect their rare assets in space by themselves. As such, the handful of resistant states is preventing the international community from collectively safeguarding the world by addressing and mitigating current and future space-related threats. A few states have abused the rule of consensus to effectively veto anything that deviates from their own legally-binding instruments, including the title of the working group itself. What states ought to be engaging in is multilateral consensus-driven negotiations to reach agreements on vital issues of common interest, thus guaranteeing the peace and predictable governance of outer space. The rapid expansion of China’s nuclear forces calls into question fundamental assumptions about how the United States can deter nuclear-armed adversaries. In this context, Congress appointed a bipartisan commission of 12 former government officials to assess the threat environment and make recommendations on the nation’s strategic posture. The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, released in October, marks the start of an inchoate debate about how to respond to China’s buildup, the outcome of which will shape the U.S. nuclear arsenal for decades.

The rapid expansion of China’s nuclear forces calls into question fundamental assumptions about how the United States can deter nuclear-armed adversaries. In this context, Congress appointed a bipartisan commission of 12 former government officials to assess the threat environment and make recommendations on the nation’s strategic posture. The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, released in October, marks the start of an inchoate debate about how to respond to China’s buildup, the outcome of which will shape the U.S. nuclear arsenal for decades. Confronting these complex questions, the commission reached a simple answer: an across-the-board buildup of U.S. nuclear forces. Its report recommends pursuing increases in the size, diversity, and alert status of every nuclear system, including multiple warheads and road-mobile options for new intercontinental missiles, more cruise missiles, more bombers postured on continuous alert with more tankers to support them, more submarines, more capability to penetrate adversary air and missile defenses, and demanding requirements for new theater nuclear options to attempt to control escalations.

Confronting these complex questions, the commission reached a simple answer: an across-the-board buildup of U.S. nuclear forces. Its report recommends pursuing increases in the size, diversity, and alert status of every nuclear system, including multiple warheads and road-mobile options for new intercontinental missiles, more cruise missiles, more bombers postured on continuous alert with more tankers to support them, more submarines, more capability to penetrate adversary air and missile defenses, and demanding requirements for new theater nuclear options to attempt to control escalations. Saudi officials have said little publicly about its negotiations on a nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States, but the country has announced ambitious plans to expand its nascent nuclear program by purchasing two large nuclear reactors and enriching domestically mined uranium.

Saudi officials have said little publicly about its negotiations on a nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States, but the country has announced ambitious plans to expand its nascent nuclear program by purchasing two large nuclear reactors and enriching domestically mined uranium. Iran was prohibited from importing and exporting certain missiles, drones, and related technologies without prior UN Security Council approval under Resolution 2231, which endorsed the 2015 nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

Iran was prohibited from importing and exporting certain missiles, drones, and related technologies without prior UN Security Council approval under Resolution 2231, which endorsed the 2015 nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The U.S. mission to the United Nations said on Oct. 13 that North Korea shipped more than 1,000 containers of arms and munitions to Russia “in recent weeks.” The transfers “directly violate” UN Security Council resolutions prohibiting North Korea from exporting arms and munitions, the statement said.

The U.S. mission to the United Nations said on Oct. 13 that North Korea shipped more than 1,000 containers of arms and munitions to Russia “in recent weeks.” The transfers “directly violate” UN Security Council resolutions prohibiting North Korea from exporting arms and munitions, the statement said.