October 2019

By Renata Dwan

On the face of it, women in the arms control field have had a good year, with gender equality featuring frequently in national and multilateral policy debates. Beyond the traditionally women-friendly humanitarian discourse, recent meetings of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) have seen side events and working papers on gender equality and perspectives ahead of the treaty’s 2020 review conference.

The first-ever side event on gender was held in the margins of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) meeting in Geneva this August. The fifth conference of states-parties to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) the same month went considerably further, convening a thematic discussion on gender and adopting a decision on gender and gender-based violence issues. New studies on the role of women in nuclear and broader arms control garnered significant attention and debate.

The first-ever side event on gender was held in the margins of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) meeting in Geneva this August. The fifth conference of states-parties to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) the same month went considerably further, convening a thematic discussion on gender and adopting a decision on gender and gender-based violence issues. New studies on the role of women in nuclear and broader arms control garnered significant attention and debate.

At the heart of gender equality is the recognition that women, as well as men, have the right to participate in debates and decision-making on matters that affect their lives and well-being. There is also a practical benefit: business and crisis management studies have indicated that diverse teams tend to be more innovative and effective in anticipating problems and finding sustainable solutions. As new challenges confront the international security system, it cannot afford to keep women from the negotiating table.

Making Some Progress

Championing gender became hip in 2018. The International Gender Champions, a leadership network supporting gender equality, established a fifth chapter in The Hague, while two arms control-focused subgroups—the Disarmament Impact Group in Geneva and the Gender Champions in Nuclear Policy in Washington—were set up to support and advocate for increased engagement on gender issues. Although gender is recognized as encompassing women and men, girls and boys, as well as nonbinary or gender-fluid persons, discussion of gender in arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament forums over the past year focused predominantly on women and their participation.

What explains this newfound interest? The #MeToo movement against sexual harassment and assault that spread virally in late 2017 undoubtedly prompted international attention and awareness of the particular challenges that women face, especially in the workplace. It shined a spotlight on efforts, some long-standing, to mainstream gender issues in international and national policymaking, including the landmark Security Council resolution in 2000 on the issue of women, peace, and security (WPS), which called for the increased participation of women in peace and security decision-making. Sweden broke new ground in 2014 by becoming the first country to systematically apply a gender equality perspective in its foreign policy, and last year, Canada adopted a feminist international assistance policy.

In 2017, newly appointed UN Secretary-General António Guterres pledged to achieve gender parity in UN senior leadership appointments by 2021 and across the entire system “well before 2030.” The African Union, European Union, and NATO have established dedicated representatives for WPS issues with mandates to advance the integration of gender issues across their respective organization’s policies and actions.

Still Behind the Curve

Despite this progress, the fields of multilateral arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament, with the notable exception of small arms and light weapons issues, has remained relatively removed from the gender-mainstreaming trend. A 2019 study by the UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) found that gender inequality persists in disarmament diplomacy, with women comprising just 32 percent of participants in disarmament-related meetings over the past 40 years.1 In related but smaller forums, such as groups of governmental experts, the number drops to 20 percent. UNIDIR sought to understand whether this was a reflection of diplomacy trends more generally, so it compared this figure to other UN General Assembly bodies and found that the main committee dealing with disarmament and international security—the First Committee—had the lowest proportion of women present. The body with the highest proportion of women (49 percent in 2017) was the Third Committee, dealing with social, humanitarian, and cultural issues. So far, so gender stereotyped.

When UNIDIR looked within the different domains of disarmament diplomacy, the typecasting was more difficult to discern. A common observation, for example, is that women tend to engage more on weapons such as cluster munitions or anti-personnel mines, which were the focus of major international humanitarian campaigns. UNIDIR did not discover any significant difference between the proportion of women participating in nuclear-related forums such as the NPT preparatory committees compared to women delegates at the Convention on Cluster Munitions (roughly 33 percent each in 2018). This could reflect the fact that the disarmament diplomacy community is relatively small, with many of its representatives covering a broad swath of arms-related issues and forums. Certainly, other analysts have identified hierarchies within the community, with fields such as nuclear posture and deterrence policy described as being much more “insulated, male-dominated and unwelcoming” compared to the arms control and nonproliferation arena or the nongovernmental advocacy sector, which are perceived to be more open to including women.2

Inevitably, the representation of women in multilateral arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament processes differs widely across regions. The statistics reveal, however, that gender equality in arms control cannot be neatly framed as a global North versus global South issue. The Latin America and the Caribbean regional group of states has the highest proportion of women delegates to multilateral forums, at close to 40 percent. African delegations have the lowest proportion of women delegates, but are among the most active in promoting gender perspectives in forums addressing small arms and light weapons from the WPS agenda to the ATT. There is a consistent correlation, however, between national income levels and gender-balanced delegations in arms control bodies, a pattern that underscores the increased emphasis being put on promoting gender equality as an integral part of poverty reduction and development.3

Inevitably, the representation of women in multilateral arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament processes differs widely across regions. The statistics reveal, however, that gender equality in arms control cannot be neatly framed as a global North versus global South issue. The Latin America and the Caribbean regional group of states has the highest proportion of women delegates to multilateral forums, at close to 40 percent. African delegations have the lowest proportion of women delegates, but are among the most active in promoting gender perspectives in forums addressing small arms and light weapons from the WPS agenda to the ATT. There is a consistent correlation, however, between national income levels and gender-balanced delegations in arms control bodies, a pattern that underscores the increased emphasis being put on promoting gender equality as an integral part of poverty reduction and development.3

Perhaps the most revealing illustration of how far arms control lags in gender equality is the number of women in leadership positions. The proportion of male heads of delegation is consistently higher than the proportion of male representatives overall for every single one of the 84 multilateral disarmament forums UNIDIR studied. Thus, although the gap between women and men may be decreasing, it is not yet reflected in the number of women leading delegations. In 2018, for example, 76 percent of delegation heads in the UN General Assembly First Committee, the Conference on Disarmament (CD), and the NPT preparatory committee meetings were men, higher than the 66 percent overall proportion of male delegates. The corresponding 24 percent of women heads of delegations at these meetings was lower than the overall 34 percent of women delegates present. Furthermore, the chances of hearing women’s voices is also small. In 2018 just 21 percent of statements in the First Committee’s general debate were delivered by women. Women may be entering the arms control room, but they are not yet at the table, much less the podium.

Explaining Slow Progress

Many complex factors explain the slow rate of gender mainstreaming in disarmament diplomacy. Structural, societal, and psychological factors play important roles, and unraveling these can reveal deep-seated and often culturally based beliefs about the innate abilities and roles of men and women.

Nevertheless, three themes recur in every study or discussion as critical obstacles to advancing gender in disarmament diplomacy: the characteristics of the arms control field itself, the practical challenges of work-life balance in diplomacy in general and disarmament diplomacy in particular, and the lack of role models for women in this domain.

Arms control is a field that places a high premium on technical expertise and, in some national and multinational systems, encourages specialization and life-long careers. This fosters, some argue, a focus on technical instead of policy questions that might encourage broader engagement or linkages with other international security topics. In multilateral arms control forums, considerable emphasis is placed on commitment to established positions, military experience in some cases, and authority borne of deep knowledge of the relevant historical processes and technical aspects of a subject. These traits can encourage caution or even resistance to outsiders and thinking that questions or challenges established approaches or ways of working. Most people in the field today would agree that the arms control endeavor faces serious challenges and may require fresh thinking, but there is a prevailing culture of status quo that sees diversity as something to be tolerated rather than enthusiastically embraced. An arms control meeting’s side event on gender, for example, typically draws few senior white men and illustrates how gender inclusion in arms control is regarded by some to be at least irrelevant and at most distracting.

The practical demands of diplomacy for families and work-life balance are not specific to arms control, but constitute a serious obstacle for many women. Arms control meetings, particularly treaty review conferences, are weeks- or months-long affairs, and frequent travel abroad for extended periods poses practical and emotional child care challenges. In multilateral settings, meetings typically start at 10 a.m., involve a two-hour lunch break, and finish at 6 p.m., a rhythm that does not reflect the school day in any country. Negotiations over the final days routinely continue beyond midnight and are so engrained in the culture of disarmament diplomacy that there is almost a spirit of competitiveness to go, and a sense of failure for the delegate unable to make it, to the bitter end. Although these practical barriers are not specific to gender, an unequal division of family tasks is still the reality for many women around the world. Moreover, the perception that a woman may be the primary child care provider or household manager can often play into recruitment and appointment decisions by senior managers.

The third theme raised by many women to explain the slow progress of gender mainstreaming in disarmament is the lack of women role models, particularly at senior levels. Multiple studies have underscored the importance of formal and informal role models, mentoring, and networks in national and international institutions and subject fields to support and encourage younger women to enter and more importantly stay in the arms control environment. This is particularly the case given the still-limited visibility of women in the field and the uncertain or at least unclear career path that such a specialized field can present for an early or midcareer professional.

Getting Past a Step-by-Step Approach

At the rate of current progress, it will take another two decades to reach gender parity in disarmament diplomacy and almost another five decades, until 2065, before gender balance among heads of delegations will be achieved. Moreover, the assumption that gender perspectives and issues will naturally evolve onto the agenda of new or emerging arms control issues is not borne out by fact. Although retrofitting gender into established conventions, such as the Mine Ban Treaty, is currently underway, there has been no sustained consideration of gender in current discussions on possible new governance arrangements involving cybersecurity, lethal autonomous weapons systems, or outer space.

Looking to tertiary educational strategies or national civil service reform to bring women into arms control or assuming that a woman in the room constitutes gender awareness or perspective will not suffice. The arms control community needs a conscious effort to build awareness of, support for, and targeted actions to mainstream gender across the field. Five possible areas for engagement would help achieve this goal.

Focus on Leadership

Although women were permitted entry into the professional levels of national foreign services relatively late, they are enthusiastically joining these services and international organizations around the world. Indeed, gender balance has been achieved among entry-level positions in organizations such as the United Nations and many national foreign services. Furthermore, academia has achieved considerable progress in adding women to traditionally male-dominated subjects such as physics. Today’s challenge has moved from attracting women to disarmament diplomacy to retaining women in the field. For this to happen, women need a viable career path.

Numerous examples show how conscious efforts to promote women's leadership can achieve progress at national levels. For example, in Sweden, home of the feminist foreign policy, the government in the 1970s introduced gender equality steps, such as generous parental leave arrangements, to encourage women into the workforce. Yet, as late as 1996, only 10 percent of Sweden’s ambassadors were women. Twenty years later, 40 percent are women after special measures were introduced to increase the number of women applicants for management positions. A gender-parity strategy, one that sets objectives and targets and establishes and tracks baselines, enables ministries to identify patterns and put in place practical, targeted steps to enhance gender balance. These can include, as in Australia or Korea, management targets; preferences for women where there are two equally qualified applicants (Norway); addressing gender pay inequalities (Switzerland); or the creation of a dedicated unit to prevent and combat discrimination (France). Management in international security, export controls, and arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament sections of ministries should be part of any such baselines reviews and targets.

At the multilateral level, the United Nations has signaled its commitment to and support for greater visibility for women in arms control. Women have been appointed to leadership positions, including as the high representative for disarmament affairs, the head of the Office of Disarmament Affairs in Geneva, and the CD secretary. The secretary-general has established quotas for women’s participation in Groups of Governmental Experts. This has had an immediate effect on participation. Although experts groups in 2018–2019 on nuclear disarmament verification and outer space saw participation of less than 7 percent and 17 percent, respectively, the number of women participating in the upcoming experts group on information and communications technology and international security is 44 percent. A similar effect is expected for next year’s group regarding ammunition.

At the multilateral level, the United Nations has signaled its commitment to and support for greater visibility for women in arms control. Women have been appointed to leadership positions, including as the high representative for disarmament affairs, the head of the Office of Disarmament Affairs in Geneva, and the CD secretary. The secretary-general has established quotas for women’s participation in Groups of Governmental Experts. This has had an immediate effect on participation. Although experts groups in 2018–2019 on nuclear disarmament verification and outer space saw participation of less than 7 percent and 17 percent, respectively, the number of women participating in the upcoming experts group on information and communications technology and international security is 44 percent. A similar effect is expected for next year’s group regarding ammunition.

Address Work-Life Balance

Practical steps could go a long way to making the arms control and disarmament environment more family friendly and open to women’s and men’s participation. New technologies, for example, are woefully underutilized today, but they could allow a reconsideration of “essential” travel. Tools to enable remote participation, such as video conferencing, online streaming of events, working group chat rooms, or the online approval of procedural issues could make meeting participation far more convenient. Other measures might examine schedule needs. Are seven working days of general debate, stretching over a weekend, actually needed when delegations are simply reading a prepared statement? Perhaps such general statements could be posted online in advance to give delegations the opportunity to read and assess each other’s positions more thoroughly before holding in-person thematic or subject-specific discussions. Such changes could also ease the financing challenges facing the United Nations and many disarmament forums, such as the BWC, where some member states fail to pay their dues.

Other practical steps could include avoiding late-night negotiations and, in instances where they are required, providing adequate advance warning so that delegates can pursue child care options. Scheduling departmental or team meetings, where possible, between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. is a step that many civil services have tried to institutionalize, along with flexible work arrangements to enable staff to work from home or manage family obligations.4 Using alternate heads of delegations’ arrangements could help share the administrative burden and boost women’s exposure opportunities as well. Encouraging women members of delegations to deliver thematic statements could help everyone become accustomed to hearing to women’s voices in arms control forums.

Promote Mentorship Networks

Mentorship is a strong feature of the arms control community, traditionally in the context of a senior man identifying, coaching, or promoting a junior man who will learn from and ultimately succeed the veteran diplomat in his functions. In this environment, networks of “old hands” play an outsized role in formal and informal diplomacy. Women can benefit equally from such networks and support. Several women-focused networks, such as Women in International Security (WIIS)’s next-generation program, have been established in arms control today, and more are emerging. So far, these have mostly targeted younger women.

Informal networks and mentoring can also serve midcareer and senior women by supporting their active participation and helping them manage the weight of expectations that many feel when assuming a leadership role in arms control. One example at the highest echelons was the summit of women foreign ministers that Canada and the EU cohosted in 2018, but other, more workaday options include womens' WhatsApp groups in disarmament forums to encourage each other to contribute, regular meetings of gender-balanced bureaus to help meeting chairpersons ensure that gender perspectives are considered in the planning and conduct of meetings, and structured mid- and senior-career mentoring programs in national and international organizations. Maintaining and circulating lists of women experts in specific arms control topics is another way in which networks can address gender balance, as well as perceptions of the role of women in expert forums.

Tackle Unconscious Bias

There is not a woman in the field who does not routinely navigate a “manel”; appear on participant lists by name while her male counterparts’ formal titles are included; grimace as she is introduced as a woman rather than an expert; groan at weapons’ terminology in all its cocked, thrust, and penetrative glory; make clothing choices depending on where her delegation is sitting; consider whether her tone is sufficiently friendly to avoid being “pushy” or “aggressive”; or have strategies for small talk at receptions that give no hint of availability. Many men are genuinely dumbstruck when they are made aware of the mundane realities of being a woman in arms control. At a most basic level, gender awareness-raising should be a mandatory part of basic training and on-the-job training for all diplomats and disarmament officials.

Other steps that can help tackle unconscious bias include greater use of gender disaggregated data, that is, systematically tracking and making available data about the gender composition of delegations, speakers, chairs, and topics in formal statements, as the UN Office of Disarmament Affairs has done for some meetings. Making chairpersons and bureaus gender aware can also contribute to the tone and focus of discussions, as well as their practical organization.5

Creating a gender-equal culture is ultimately about assigning value to diversity and change, and that requires fundamental shifts to the culture of the arms control community. As the organizers of the 2019 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace nuclear conference concluded, achieving gender-balanced panels means reaching out to younger and more diverse experts. Rethinking longevity as a priority value for advancement in arms control and contemplating career breaks for women and men to prioritize child care may be required. Embracing empathy and negotiation skills may encourage a little less emphasis on attributes such as toughness or risk-taking, which are associated wrongly with men. It may also mean accepting the participation of women who have built their careers in other fields of international security. Acknowledging linkages between arms control and other domains and pursuing opportunities to integrate arms control into broader international security, peace, and gender agendas may not only advance women’s participation in disarmament but encourage new perspectives and thinking on arms control. As discussions on new technologies have illustrated, broadening the field does not automatically “gender” the field without conscious efforts being made to do so.

Bring Gender Into Substantive Discussions

The gender debate in arms control, with notable exceptions in the areas of small arms, landmines, cluster munitions, and the language of the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, remains largely a debate about women’s participation. This can appear to some as technical, an issue more for human resources than for arms control, hence the view of some of gender as a potential “bridge-building” topic in the NPT. Some observers also concluded that the prioritization of gender in this year’s ATT states-parties meeting “distracted” delegates from discussing more “fundamental” and “political” issues.

To achieve the full and meaningful participation of women, gender mainstreaming must go beyond numbers to encompass the assumptions and ways in which the world defines, makes, and implements control over weapons. It means asking who controls a weapon, who is affected by it, and how. It means looking at the ways in which security, power, and authority are defined. Mainstreaming gender in disarmament diplomacy, according to Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, means offering a feminist perspective on the root causes of conflict and redefining security away from military strength. In this context, gender mainstreaming is a transformative agenda that seeks to influence not just who speaks but the substance and tools of arms control.6 It is not an issue for or by women, but a much broader normative reorientation of the agenda.

This is and will be controversial. At a minimum, introducing a gender perspective into arms control can expand the way in which arms control is perceived and pursued. Gender analysis frameworks can offer new ways of formulating the objectives and targets of specific weapons regulation while gender-disaggregated data and budgets can open new avenues to assess their impact and effectiveness. As the community grapples to navigate the security implications of dual-use technologies and how to regulate intangible algorithms, exploring new ways of understanding and framing weapons regulation may offer new pathways for the profession to advance progress. Might feminism revive arms control?

ENDNOTES

1. Renata Hessmann Dalaqua, Kjølv Egeland, and Torbjørn Graff Hugo, “Still Behind the Curve: Gender Balance in Arms Control, Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Diplomacy,” UN Institute for Disarmament Research, 2019, http://www.unidir.org/files/publications/pdfs/still-behind-the-curve-en-770.pdf.

2. See Heather Hurlburt et al., “The ‘Consensual Straitjacket’: Four Decades of Women in Nuclear Security,” New America, March 2019, https://www.newamerica.org/political-reform/reports/the-consensual-straitjacket-four-decades-of-women-in-nuclear-security/.

3. For more, see Naila Kabeer and Luisa Natali, “Gender Equality and Economic Growth: Is There a Win-Win?” IDS Working Paper, No. 417 (February 2013); World Bank Group, “World Bank Group Gender Strategy (FY16–23): Gender Equality, Poverty Reduction and Inclusive Growth, n.d., http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/820851467992505410/pdf/102114-REVISED-PUBLIC-WBG-Gender-Strategy.pdf.

4. For a more comprehensive discussion, see Anne-Marie Slaughter, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” The Atlantic, July–August 2012.

5. For example, see International Gender Champions Disarmament Impact Group, “Gender and Disarmament Resource Pack for Multilateral Practitioners,” January 2019, http://www.unidir.org/files/publications/pdfs/gender-disarmament-resource-pack-en-735.pdf.

6. For example, Karin Aggestam and Annika Bergman Rosamond, “Re-politicising the Gender-Security Nexus: Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy,” ERIS, Vol. 5, No. 3 (2018): 30–48.

Renata Dwan is director of the UN Institute for Disarmament Research. The author thanks Renata Hessmann Dalaqua for her insights and comments.

Today, a new generation is mobilizing to demand dramatic action to address another existential threat: the human-induced climate emergency. The scientific consensus is that climate change causes and impacts are increasing, and little more than a decade is left to take the bold steps necessary to cut global carbon emissions in half and reverse the slide toward catastrophe.

Today, a new generation is mobilizing to demand dramatic action to address another existential threat: the human-induced climate emergency. The scientific consensus is that climate change causes and impacts are increasing, and little more than a decade is left to take the bold steps necessary to cut global carbon emissions in half and reverse the slide toward catastrophe.

The first-ever side event on gender was held in the margins of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) meeting in Geneva this August. The fifth conference of states-parties to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) the same month went considerably further, convening a thematic discussion on gender and adopting a decision on gender and gender-based violence issues. New studies on the role of women in nuclear and broader arms control garnered significant attention and debate.

The first-ever side event on gender was held in the margins of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) meeting in Geneva this August. The fifth conference of states-parties to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) the same month went considerably further, convening a thematic discussion on gender and adopting a decision on gender and gender-based violence issues. New studies on the role of women in nuclear and broader arms control garnered significant attention and debate. Inevitably, the representation of women in multilateral arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament processes differs widely across regions. The statistics reveal, however, that gender equality in arms control cannot be neatly framed as a global North versus global South issue. The Latin America and the Caribbean regional group of states has the highest proportion of women delegates to multilateral forums, at close to 40 percent. African delegations have the lowest proportion of women delegates, but are among the most active in promoting gender perspectives in forums addressing small arms and light weapons from the WPS agenda to the ATT. There is a consistent correlation, however, between national income levels and gender-balanced delegations in arms control bodies, a pattern that underscores the increased emphasis being put on promoting gender equality as an integral part of poverty reduction and development.

Inevitably, the representation of women in multilateral arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament processes differs widely across regions. The statistics reveal, however, that gender equality in arms control cannot be neatly framed as a global North versus global South issue. The Latin America and the Caribbean regional group of states has the highest proportion of women delegates to multilateral forums, at close to 40 percent. African delegations have the lowest proportion of women delegates, but are among the most active in promoting gender perspectives in forums addressing small arms and light weapons from the WPS agenda to the ATT. There is a consistent correlation, however, between national income levels and gender-balanced delegations in arms control bodies, a pattern that underscores the increased emphasis being put on promoting gender equality as an integral part of poverty reduction and development. At the multilateral level, the United Nations has signaled its commitment to and support for greater visibility for women in arms control. Women have been appointed to leadership positions, including as the high representative for disarmament affairs, the head of the Office of Disarmament Affairs in Geneva, and the CD secretary. The secretary-general has established quotas for women’s participation in Groups of Governmental Experts. This has had an immediate effect on participation. Although experts groups in 2018–2019 on nuclear disarmament verification and outer space saw participation of less than 7 percent and 17 percent, respectively, the number of women participating in the upcoming experts group on information and communications technology and international security is 44 percent. A similar effect is expected for next year’s group regarding ammunition.

At the multilateral level, the United Nations has signaled its commitment to and support for greater visibility for women in arms control. Women have been appointed to leadership positions, including as the high representative for disarmament affairs, the head of the Office of Disarmament Affairs in Geneva, and the CD secretary. The secretary-general has established quotas for women’s participation in Groups of Governmental Experts. This has had an immediate effect on participation. Although experts groups in 2018–2019 on nuclear disarmament verification and outer space saw participation of less than 7 percent and 17 percent, respectively, the number of women participating in the upcoming experts group on information and communications technology and international security is 44 percent. A similar effect is expected for next year’s group regarding ammunition. Saudi Arabia insists it will not accept the so-called gold standard, a promise to refrain from enriching or reprocessing, to which neighboring United Arab Emirates (UAE) agreed in its bilateral agreement for civil nuclear cooperation with the United States.

Saudi Arabia insists it will not accept the so-called gold standard, a promise to refrain from enriching or reprocessing, to which neighboring United Arab Emirates (UAE) agreed in its bilateral agreement for civil nuclear cooperation with the United States. Then came the Trump administration and its exceptional chumminess with Saudi Arabia, which described plans to build 16 nuclear power plants. Although unlikely to happen, the Saudi plan dangled the possibility of a $100 billion sale, attracting industry moths to flame, such as IP3 International, a firm heavy with retired generals and admirals, none of whom apparently had any nuclear background. What they did have was powerful White House connections, and IP3 is now pushing for a U.S. nuclear comeback by way of nuclear exports to the Middle East, expanding the goal beyond Saudi Arabia to a U.S. nuclear “Marshall Plan” for the entire region.

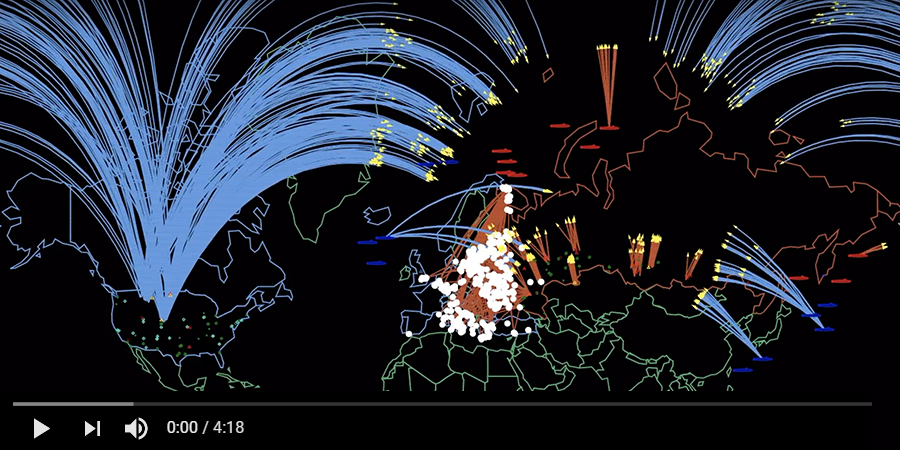

Then came the Trump administration and its exceptional chumminess with Saudi Arabia, which described plans to build 16 nuclear power plants. Although unlikely to happen, the Saudi plan dangled the possibility of a $100 billion sale, attracting industry moths to flame, such as IP3 International, a firm heavy with retired generals and admirals, none of whom apparently had any nuclear background. What they did have was powerful White House connections, and IP3 is now pushing for a U.S. nuclear comeback by way of nuclear exports to the Middle East, expanding the goal beyond Saudi Arabia to a U.S. nuclear “Marshall Plan” for the entire region. How will a great-power nuclear war erupt? How can its outbreak be prevented? These questions have bedeviled nuclear strategists and peace advocates since the dawn of the Atomic Age and are gaining fresh urgency as tensions among China, Russia, and the United States intensify.

How will a great-power nuclear war erupt? How can its outbreak be prevented? These questions have bedeviled nuclear strategists and peace advocates since the dawn of the Atomic Age and are gaining fresh urgency as tensions among China, Russia, and the United States intensify. In any of these scenarios, O’Hanlon claims, U.S. military policy would presuppose a rapid and harsh response. Yet, any U.S. drive to dislodge Russian or Chinese forces from those locations would require a major commitment of force and, given recent improvements in those countries’ combat capabilities (especially through the acquisition of high-tech weaponry), might not prove easy to accomplish. A U.S. victory would be the most likely outcome, but could prompt Russia or China to employ nuclear weapons. Far better, he argues, to counter such assaults with asymmetric moves, such as attacks on vital energy infrastructure located outside the Russian or Chinese heartland, along with the reinforcement of positions in areas near the original intrusion.

In any of these scenarios, O’Hanlon claims, U.S. military policy would presuppose a rapid and harsh response. Yet, any U.S. drive to dislodge Russian or Chinese forces from those locations would require a major commitment of force and, given recent improvements in those countries’ combat capabilities (especially through the acquisition of high-tech weaponry), might not prove easy to accomplish. A U.S. victory would be the most likely outcome, but could prompt Russia or China to employ nuclear weapons. Far better, he argues, to counter such assaults with asymmetric moves, such as attacks on vital energy infrastructure located outside the Russian or Chinese heartland, along with the reinforcement of positions in areas near the original intrusion. New START expires in February 2021, and the Trump administration has suggested it will let it lapse to pursue a more ambitious agreement involving the United States, Russia, and China. At a July 2019 congressional hearing on U.S.-Russian arms control, not a single Republican member voiced support for extending New START.

New START expires in February 2021, and the Trump administration has suggested it will let it lapse to pursue a more ambitious agreement involving the United States, Russia, and China. At a July 2019 congressional hearing on U.S.-Russian arms control, not a single Republican member voiced support for extending New START. When I started my career with the International Committee of the Red Cross [ICRC] in the early 1990s, I worked in El Salvador, at a hopeful time when we expected peace to bring violence to an end. But years after the armed conflict ended, the continued widespread availability of weapons has fueled levels of armed violence that are today among the highest in the world.

When I started my career with the International Committee of the Red Cross [ICRC] in the early 1990s, I worked in El Salvador, at a hopeful time when we expected peace to bring violence to an end. But years after the armed conflict ended, the continued widespread availability of weapons has fueled levels of armed violence that are today among the highest in the world. “We have willingness to sit with the U.S. side for comprehensive discussions of the issues we have so far taken up at the time and place to be agreed late in September,” Choe said. But she cautioned that if the U.S. side offers no new “calculation,” then “DPRK-U.S. dealings may come to an end.”

“We have willingness to sit with the U.S. side for comprehensive discussions of the issues we have so far taken up at the time and place to be agreed late in September,” Choe said. But she cautioned that if the U.S. side offers no new “calculation,” then “DPRK-U.S. dealings may come to an end.” If confirmed, the move would constitute Iran’s third breach of the six-party nuclear deal in retaliation to the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018 and Washington’s reimposition of U.S. sanctions that had been lifted. Iran’s latest step away from the nuclear accord follows its May and July 2019 decisions to enrich and accumulate uranium beyond the thresholds designated by the JCPOA. According to the agreement, Iran can store no more than 300 kilograms of uranium hexafluoride enriched up to 3.67 percent uranium-235, and it may not enrich uranium to levels higher than that for 15 years after the implementation day.

If confirmed, the move would constitute Iran’s third breach of the six-party nuclear deal in retaliation to the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018 and Washington’s reimposition of U.S. sanctions that had been lifted. Iran’s latest step away from the nuclear accord follows its May and July 2019 decisions to enrich and accumulate uranium beyond the thresholds designated by the JCPOA. According to the agreement, Iran can store no more than 300 kilograms of uranium hexafluoride enriched up to 3.67 percent uranium-235, and it may not enrich uranium to levels higher than that for 15 years after the implementation day.