October 2020

By Amy F. Woolf

The United States and the Soviet Union, later Russia, have negotiated limits on their nuclear forces for more than 50 years. Arms control has provided both nations with insights into emerging threats from the other’s forces, allowed informed decisions into the types of weapons and capabilities they could eliminate without risking their security, and maintained transparency and communication with an adversary who could kill millions of their citizens in an afternoon.

Arms control did not stop either nation from advancing its nuclear capabilities. Both replaced aging weapons systems, incorporated new technologies, and enhanced their ability to threaten the nuclear forces of the other nation. Neither saw a contradiction in the parallel efforts of negotiating limits while modernizing forces. To the contrary, many U.S. officials who have participated in the process1 and analysts who have watched it from the sidelines2 argue that the two tracks naturally go together: the United States can best achieve its preferred arms control outcomes if it negotiates from a position of strength and demonstrates that it is willing to bolster its forces if the arms control process fails.

Arms control did not stop either nation from advancing its nuclear capabilities. Both replaced aging weapons systems, incorporated new technologies, and enhanced their ability to threaten the nuclear forces of the other nation. Neither saw a contradiction in the parallel efforts of negotiating limits while modernizing forces. To the contrary, many U.S. officials who have participated in the process1 and analysts who have watched it from the sidelines2 argue that the two tracks naturally go together: the United States can best achieve its preferred arms control outcomes if it negotiates from a position of strength and demonstrates that it is willing to bolster its forces if the arms control process fails.

Marshall Billingslea, President Donald Trump’s special representative for arms control, advanced this view in May 2020, when he noted that “the risk of any cuts to the bipartisan consensus on modernization and the plans that we have that are underway, in the midst of a negotiation, is to inadvertently or otherwise hand the initiative to either Beijing or Moscow, or both. So we need to stay the course, and that will really strengthen the objective here of getting to meaningful trilateral arms control arrangements.”3 Billingslea also argued that the United States can use its economic strength to wage and win an arms race if Russia and China do not meet U.S. demands in the arms control process, saying that “we know how to win these races and we know how to spend the adversary into oblivion.”4

Those who hold the view that the United States must invest in its nuclear forces to achieve success in arms control usually begin by citing evidence of a successful negotiation, then looking backward to identify spending from years earlier. They later assert that the spending created the conditions for the successful negotiations. This paradigm, however, is not an accurate representation of the U.S.-Soviet negotiations that successfully resulted in treaties. Even when the correlation between spending and arms control exists, robust funding and modernization were not the sole cause of successful negotiations and, in some cases, may not have even been necessary.

This paradigm presumes that, with the United States negotiating from a position of strength, the nation negotiating from a position of weakness will respond by seeking to impose limits on U.S. capabilities. Yet, the weaker nation likely has a range of options besides arms control for improving its position. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union expanded some of its capabilities while agreeing to limit others and seeking limits on U.S. forces. In addition, the arms control history contains abundant evidence that the Soviet Union, even when motivated by a desire to alter the U.S.-Soviet military balance, had a number of other reasons to participate in arms control. Domestic politics, budgetary considerations, the limits of technology, and a changing political and security environment all played a role.

The argument that the U.S. economy serves as a symbol of strength that should give pause to adversaries and point them to the negotiating table is also flawed. The U.S. gross domestic product may indicate that Washington has the resources to expand funding for military programs, but it is not clear that the U.S. electorate would support this expansion or that the military, if given access to added funds, would choose to direct them toward an expanded nuclear arsenal. Further, this argument does not allow space for debates about the relative cost of nuclear modernization programs and the possible need for trade-offs among competing priorities. It simply assumes that all spending is necessary and no programs should be curtailed until an agreement is complete.

The argument that the U.S. economy serves as a symbol of strength that should give pause to adversaries and point them to the negotiating table is also flawed. The U.S. gross domestic product may indicate that Washington has the resources to expand funding for military programs, but it is not clear that the U.S. electorate would support this expansion or that the military, if given access to added funds, would choose to direct them toward an expanded nuclear arsenal. Further, this argument does not allow space for debates about the relative cost of nuclear modernization programs and the possible need for trade-offs among competing priorities. It simply assumes that all spending is necessary and no programs should be curtailed until an agreement is complete.

Still, analysts have identified several U.S.-Soviet/Russian arms control agreements that seem to validate the link between nuclear weapons spending and successful arms control. These include the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, negotiated after Congress approved funding for the Safeguard ABM system; the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, negotiated after the United States began to deploy intermediate-range missiles in Europe; the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), negotiated after the United States pursued sharp increases in funding and began to deploy new bombers, missiles, and submarines; and the 1993 START II, negotiated after the collapse of the Soviet Union when Russia experienced severe financial and political weaknesses. A closer look at these agreements, however, raises doubts about the strength of the link between spending and arms control.

The ABM Treaty

The ABM Treaty permitted the United States and Soviet Union to deploy defensive systems for interception of long-range ballistic missiles at only two sites each, one centered on the nation’s capital and one containing launchers for land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Each site could contain up to 100 ABM launchers, along with specified radars and sensors. Each nation also agreed not to develop, test, or deploy ABM systems for the “defense of the territory of its country” and not to provide a base for such a defense. In a protocol signed in 1974, each side agreed to deploy an ABM system at only one site, either around the nation’s capital or around an ICBM deployment area. The Soviet Union deployed its Galosh system around Moscow; it remains operational today. The United States deployed its Safeguard missile defense system around ICBM silo launchers near Grand Forks, North Dakota; this site operated briefly in 1974 before the United States closed it when it proved not to be cost effective.

Analysts have often linked the successful negotiation of the ABM Treaty with the U.S. pursuit of the Safeguard system. Some argue that the commitment evident in U.S. funding for offensive and defensive nuclear programs during the 1960s provided the Soviet Union with an incentive to join the negotiations. Others note that the U.S. ABM system served as a bargaining chip that it could trade away during the negotiations. Although these two views are somewhat contradictory, a weapons system could not be an example of the U.S. commitment to missile defenses and an expendable bargaining chip in the negotiations, both see the pursuit of ABM as a necessary precursor to the completion of the treaty.

Because there is no way to run a counterexperiment, with the United States seeking to limit missile defense systems without first funding Safeguard, it is not possible to dismiss a correlation between two events. Yet, it is also not clear that the U.S. ABM program caused the Soviet Union to join or conclude the talks.

First, the U.S. commitment to the Safeguard system was anything but unwavering, as the United States changed the goals and scope of its ABM program several times. Initially, the program was intended to protect the entire country from Soviet missile attacks, but the high cost and limited effectiveness of the technology made this goal elusive. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, in an effort to hold down costs while recognizing the political value of the program, announced in 1967 that the United States would instead develop a thin defense to protect U.S. cities from Chinese missiles.5 President Richard Nixon changed the program again when he unveiled the Safeguard system, which was designed to defend U.S. ballistic missile and bomber bases against a Soviet attack.

Moreover, Congress almost killed the program in 1969. Many in Congress supported the goal of protecting Americans from missile attack, but concerns about whether a limited system would be effective against a Soviet first strike generated growing skepticism. In August 1969, the Senate voted on an amendment to deny funding for the Safeguard system, while authorizing research and development on new ABM systems. The amendment failed, and many analysts point to this vote as evidence of the Senate’s support for the Safeguard system. The vote, however, was 50–51, with Vice President Spiro Agnew casting the tie-breaking vote to save the program.6 This is hardly a ringing endorsement.

Congress again debated amendments that would ban funding for the deployment of the Safeguard system in 1970. At that point, the Nixon administration argued that the United States needed the system to trade as a bargaining chip in the negotiations. Some members argued that research and development funding should be sufficient to bolster the U.S. negotiating position, while others argued that, absent a commitment to deploy the system, the United States would lack anything to trade for limits on Soviet ABM systems. The latter argument prevailed, and the Safeguard system survived again.

Because the United States and Soviet Union agreed to limit their ABM systems after the Senate twice rejected amendments to defund the Safeguard system, many analysts hold that U.S. support for the system was necessary for the successful conclusion of the treaty. Yet, Soviet leaders were likely aware of the slim congressional support for the system and therefore may have discounted its value as a bargaining chip. Moreover, Soviet leaders may have supported ABM limits if they had their own concerns about the costs and technical feasibility of missile defenses. Hence, they may have pursued limits on ABM systems even if the United States had not moved forward with the Safeguard system.

The INF Treaty

In its 1979 “dual track” decision, NATO responded to concerns about the Soviet deployment of SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles by supporting the deployment of new U.S. missiles in Europe and the negotiation of an arms control arrangement that would limit the deployment of these missiles. After early discussions in 1980, the United States and Soviet Union pursued formal negotiations from 1981 to 1983. The Soviet Union withdrew from the talks when the United States began to deploy the new missiles in 1983, but it returned in 1985, and the two nations signed the INF Treaty on December 8, 1987.

The treaty banned the testing, production, and deployment of all land-based, intermediate-range and shorter-range ballistic missiles and ground-launched cruise missiles, which are those missiles with a range between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The Soviet Union destroyed approximately 1,750 missiles, including SS-20 ballistic missiles, which carried three warheads each, and a number of other older, shorter- and medium-range missiles. The United States destroyed 846 missiles, including Pershing II ballistic missiles and Gryphon ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs). The treaty permitted on-site inspections of missile assembly facilities, storage centers, deployment zones, and repair, test, and elimination facilities for the missiles eliminated under the treaty and established a continuous portal monitoring procedure at one assembly facility in each country.

Analysts often cite the treaty as a near-perfect example of how the United States leveraged the development and deployment of new nuclear delivery systems to achieve its arms control objectives. One has argued that “the United States compelled the Soviet Union to enter the INF Treaty” after it deployed hundreds of “accurate and lethal intermediate-range missiles.”7 Another noted that “the treaty worked because the Soviets came to realize that...they faced the threat of a no-warning strike on critical command and control targets in Moscow.”8 Yet, the success of the INF Treaty negotiations cannot be attributed solely to the NATO decision, the U.S. deployment, and the Soviet fear of these weapons. The story is incomplete without an understanding of the rationale for the dual-track decision and the reality of the political environment at the time.

Rationale for the Dual-Track Decision

During the Cold War, the United States deployed nuclear weapons in Europe to convince the Soviet Union and U.S. allies in NATO that the United States would defend the allies if they were attacked by the Soviet Union. Some allies began to question this commitment in the late 1970s as the Soviet Union deployed growing numbers of long-range missiles with the range to strike the United States. They doubted that the United States would defend them if the Soviet Union could respond with nuclear attacks against the United States. In addition, the relatively short range of many U.S. nuclear weapons meant they were based near the potential front lines of a conflict in West Germany. Because their use would have caused extensive damage on West German territory, some questioned whether NATO would actually employ the weapons early in conflict, when they might deter or repel a Soviet invasion.9

The Soviet deployment of SS-20 intermediate-range missiles complicated this problem. NATO lacked a comparable missile that could reach into Soviet territory from Europe. Further, the Soviet threat to use these missiles against capitals in Western Europe while wielding the implicit threat to retaliate against U.S. territory could have “decoupled” the defense of Europe from the defense of the United States. Yet, the problems that prompted the dual-track decision—the relatively short range of NATO’s theater nuclear weapons and the vulnerability of the United States to Soviet retaliation—would not have disappeared if the SS-20 missiles did not exist. NATO made this clear when announcing this decision: the United States needed to modernize its intermediate-range capabilities even if the Soviet Union agreed to limit its SS-20 missiles.

The INF Negotiating Process

The United States and its NATO allies recognized that the Soviet Union would be unlikely to negotiate away its SS-20 missiles unless it faced a similar threat from U.S. intermediate-range systems. Few, however, expected the Soviet Union to agree to the complete elimination of its SS-20 missiles, and the United States did not plan to negotiate such a ban. U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s administration initially sought an agreement that would impose equal limits on both sides’ intermediate-range missiles. The Soviet Union countered by proposing that the two sides simply freeze the numbers of medium-range systems in Europe. This meant that it would stop deploying but would not reduce its deployments of SS-20 missiles in exchange for the cancellation of all Pershing II and GLCM deployments.10 Neither proposal was acceptable to the other side.

The zero option for intermediate-range missiles appeared in November 1981, when U.S. President Ronald Reagan announced that the United States would seek the total elimination of Soviet SS-20, SS-4, and SS-5 missiles in return for the cancellation of NATO’s deployment plans. The Soviet Union proposed instead that the two sides agree to a phased reduction of all medium-range nuclear weapons (those with a range of 1,000 kilometers) deployed in and around Europe. This would have included Soviet missiles in Asia and would have captured some U.S. aircraft based in Europe and U.S. sea-launched cruise missiles. During 1982 and 1983, the United States and Soviet Union discussed possible compromises that would balance the numbers of U.S. and Soviet missiles, but these discussions made little progress. The Soviet Union withdrew from the negotiations when the United States began to deploy its intermediate-range missile systems in late 1983.

The negotiations resumed in March 1985 and began to gain traction in 1986. Between the Reykjavik summit in October 1986 and June 1987, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev offered several evolving proposals. He first suggested that all intermediate-range missiles—the SS-20s, GLCMs, and Pershing IIs—be removed from Europe, although some would remain deployed in Asia. He then indicated that the Soviet Union was prepared to eliminate all of its shorter-range missiles (those with ranges between 300 and 600 miles) in Europe and Asia. Finally, he proposed a global ban on shorter-range and longer-range systems, essentially accepting the U.S. zero-option proposal from 1982.

The Changing Political Landscape

Some have argued that the Soviet return to the INF Treaty negotiations in 1985 and the eventual conclusion of a treaty that reflected the original U.S. negotiating position demonstrate the success of the U.S. effort to negotiate from a position of strength. U.S. missiles, however, were not the only addition to the landscape between 1983 and 1985. Gorbachev had become the general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. His desire to transform the Soviet Union, politically and economically, provided a strong incentive for him to pursue arms control, not just to limit U.S. forces but also to limit the burden on the Soviet Union. These factors almost certainly contributed to his eventual embrace of a complete ban on intermediate-range missiles.

Consequently, even if the Soviet Union sought to limit the threat from U.S. missiles, the changing political landscape after 1985 had as much if not more influence on the eventual conclusion of the INF Treaty. Moreover, because the Soviet Union, before Gorbachev, reacted to the U.S. deployment of intermediate-range missiles by withdrawing from the negotiations, the deployments themselves were unlikely to provide a sufficient incentive for arms control, absent the change in political leadership.

START

The United States and Soviet Union signed START on July 31, 1991. The negotiations began in 1982, but stopped between 1983 and 1985 after a Soviet walkout in response to the U.S. deployment of intermediate-range missiles in Europe. The negotiations resumed in 1985 and concluded shortly before the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991. A protocol signed in 1992 named four former Soviet republics—Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine—as the successors to the Soviet treaty obligations.

START limited long-range nuclear forces—land-based ICBMs, submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers—in the United States and the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. Each side was allowed to deploy up to 6,000 attributed warheads on 1,600 ballistic missiles and bombers. (Some weapons carried on bombers did not count against the treaty’s limits.) Each side could deploy up to 4,900 warheads on ICBMs and SLBMs. START also limited each side to 1,540 warheads on heavy ICBMs, equating to a 50 percent reduction in the number of warheads on Soviet SS-18 ICBMs. The United States placed a high priority on reductions in these missiles because they were thought to be able to threaten a first strike against U.S. ICBMs.

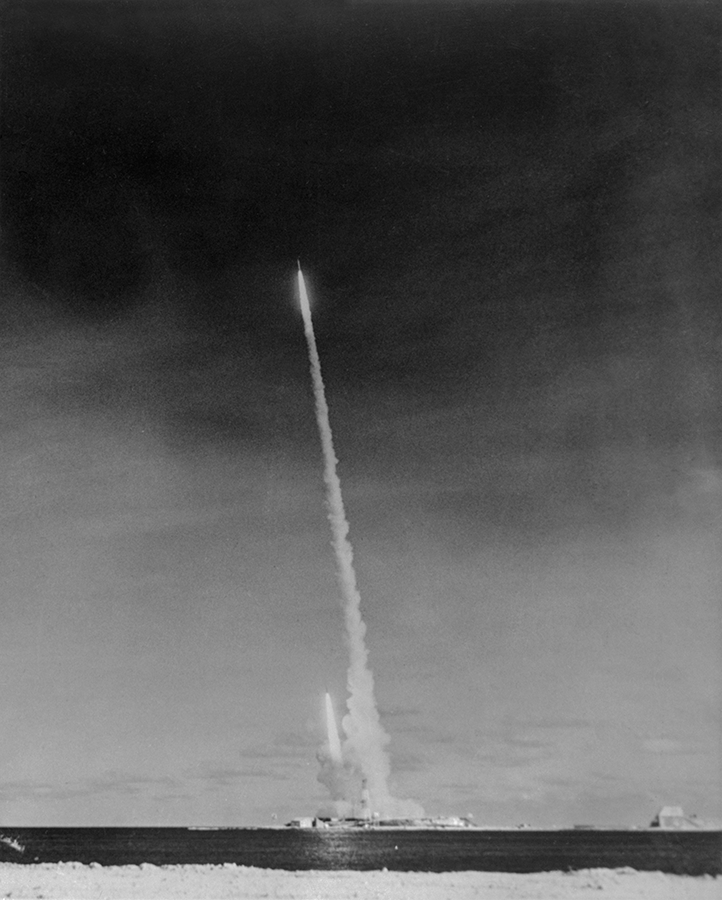

The Reagan administration actively advanced the notion that the United States needed to build up its military capabilities so that it could negotiate from a position of strength in START. U.S. defense spending increased by 34 percent between 1981 and 1986, rising from $317 billion to $426 billion before flattening during the rest of the Reagan administration. The administration revived the B-1 bomber program, which had been canceled by the Carter administration; began production of the MX Peacekeeper ICBM; and pursued development of the Ohio-class (Trident) submarines and Trident II (D-5) SLBMs.

Some argue that the “Reagan buildup” allowed the United States to achieve its goals in the START negotiations. One analyst even stated that the U.S. deployment of Trident and Peacekeeper missiles “hastened” the conclusion of START.11 This narrative is flawed. First, although defense budgets increased during the early 1980s, there was no progress on START while the budgets were rising. Moreover, in 1983, while the budgets were still rising, the Soviet Union walked out of the negotiations, and the budget increases had stalled before the negotiations resumed and began to progress in 1986. Second, although U.S. modernization programs may have provided the Soviet Union with an incentive to reach an agreement, they did not “hasten” the process and may actually have slowed it down. The United States and Soviet Union began START talks in 1982 and signed the treaty in 1991, a period of nine years that vastly exceeded the four years needed to conclude the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks agreement in 1972 and the five years needed for the INF Treaty in 1987. Further, during the final years the pace slowed while the two parties sought to identify limits and counting rules for all new U.S. capabilities.

The Reagan administration also advanced the bargaining chip argument to sustain support for the MX missile during the negotiations.12 Congressional support for the missile had waned in the early 1980s as members raised questions about the cost and feasibility of the basing schemes that were designed to reduce the missile’s vulnerability. The 1983 Scowcroft Commission also recognized that a vulnerable missile could undermine stability, but it recommended that the United States deploy MX missiles in vulnerable silos and justified this in part by noting that the missile could serve as a bargaining chip to win reductions in Soviet heavy ICBMs. Yet, the MX missile never really served as a bargaining chip. There is no evidence that the Reagan administration planned to cancel the missile, and START limits did not restrain the program. Although the United States agreed to eliminate these missiles in the 1993 START II, there was no way to see this coming during the debates over the missile in 1983.

Moreover, as was the case with the INF Treaty, political changes in Russia played a significant role in the completion of START. Gorbachev became the general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in 1985. His proposals for deep cuts in nuclear weapons, which nearly led to an agreement on nuclear weapons abolition at the Reykjavik summit, were a reflection of the political will he brought to the negotiations. Reagan also changed his views on the value of arms control in his second term and seemed to favor a more idealistic approach toward the abolition of nuclear weapons. Hence, the U.S. buildup of the early 1980s may have been a contributing precursor to START, but the successful completion of the treaty owes as much if not more to the changing political environment in the later years of the talks.

START II

The United States and Russia signed START II on January 3, 1993, after less than a year of negotiations. The treaty would have limited each side to between 3,000 and 3,500 warheads. It would have banned all multiple-warhead land-based ICBMs and would have limited each side to 1,750 warheads on SLBMs. This would have led to the elimination of the U.S. MX missiles and all Russian SS-18 and SS-24 ICBMs.

START II is an unambiguous case in which the United States negotiated from a position of strength and achieved advantageous outcomes in the resulting arms control treaty. The United States fulfilled its primary arms control goal of the previous 20 years: the elimination of Soviet SS-18 heavy ICBMs. It had to cash in the MX missile “bargaining chip” to win this concession, but in the absence of an acceptable mobile basing mode and diminishing concerns about a Soviet first strike, the Pentagon’s interest in the MX missile had dissipated. Further, many in the United States hoped that further reductions in the U.S. arsenal would produce a “peace dividend” and allow lower defense spending. In addition, Russian President Boris Yeltsin recognized that Russia lacked the financial resources to maintain aging Soviet systems at the levels permitted by START. Recognizing this dynamic, both nations moved quickly to negotiations on START II.

START II, however, also presents a clear case of how a treaty negotiated when one party is operating from a position of weakness can fail to achieve its expected goals. Russian officials immediately raised concerns about Russia’s financial and technical ability to maintain its forces at START II levels. The ban on multiple-warhead ICBMs would have cut deeply into the number of Russian ICBM warheads, and financial pressures would cut into Russia’s ballistic missile submarine force. At the same time, other U.S. policies and programs repeatedly reminded Russia of its position of weakness. NATO enlargement raised concerns in Russia about its relative position in Europe and the security situation near its borders. NATO engagement in Kosovo in 1999 reminded Russia of its reduced status in the international community. The United States continued to press forward with ballistic missile defense programs, and in 2002, when the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty, Russia officially withdrew from START II.

START II, however, also presents a clear case of how a treaty negotiated when one party is operating from a position of weakness can fail to achieve its expected goals. Russian officials immediately raised concerns about Russia’s financial and technical ability to maintain its forces at START II levels. The ban on multiple-warhead ICBMs would have cut deeply into the number of Russian ICBM warheads, and financial pressures would cut into Russia’s ballistic missile submarine force. At the same time, other U.S. policies and programs repeatedly reminded Russia of its position of weakness. NATO enlargement raised concerns in Russia about its relative position in Europe and the security situation near its borders. NATO engagement in Kosovo in 1999 reminded Russia of its reduced status in the international community. The United States continued to press forward with ballistic missile defense programs, and in 2002, when the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty, Russia officially withdrew from START II.

Russia accepted the terms of START II because it was negotiating from a position of weakness. It withdrew from START II, after facing frequent reminders of that weakness, so that it could improve its position with a wide-ranging nuclear modernization program. Because START II never entered into force, Russia never eliminated its SS-18 ICBMs and will soon replace them with a new 10-warhead Sarmat ICBM. After walking away from START II, it initiated several programs designed to ensure that its nuclear forces can penetrate emerging U.S. missile defenses. Few would argue that the United States, after achieving its goals in the START II negotiations, remained in the same position of strength when START II did not enter into force.

Conclusion

During the Cold War, the United States often expanded its nuclear weapons capabilities. It also occasionally reached agreements with the Soviet Union to reduce those capabilities. The funding for new programs sometimes preceded the negotiated reductions. That does not mean that funding was always a necessary precursor to the reductions or that the existence of new weapons programs caused the eventual arms control outcome. Arguing that the United States must always negotiate from a position of strength to achieve its preferred arms control outcome serves less as an explanation of the conditions that contributed to arms control in the past than as an excuse for continued funding for all nuclear weapons programs in the future.

ENDNOTES

1. Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. negotiator for the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), noted that “[p]eriods of success in negotiations are followed by droughts, because of politics, military upheaval, arms buildups—yes, sometimes the weapons have to be built before they can be reduced—or a sense of complacency.” Rose Gottemoeller, “U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Control Negotiations: A Short History,” The Foreign Service Journal, May 2020, p. 26, http://www.afsa.org/sites/default/files/may2020fsj.pdf.

2. One proponent of this view stated, “If Congress wants to promote genuine progress on arms control with great power rivals like Russia and China, it should forget restraint and double down on superiority.” John Maurer, “Post INF Great Power Arms Control,” Real Clear Defense, September 17, 2019, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2019/09/17/post_inf_great_power_arms_control_114747.html.

3. “Special Presidential Envoy Marshall Billingslea on the Future of Nuclear Arms Control,” Hudson Institute, May 21, 2020, p. 9, https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.hudson.org/Transcript_Marshall%20Billingslea%20on%20the%20Future%20of%20Nuclear%20Arms%20Control.pdf.

4. Jonathan Landay, “U.S. Prepared to Spend Russia, China ‘Into Oblivion’ to Win Nuclear Arms Race: U.S. Envoy,” Reuters, May 21, 2020.

5. James Cameron, The Double Game: The Demise of America’s First Missile Defense System and the Rise of Strategic Arms Limitation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 94-95.

6. Ibid., p. 123.

7. Maurer, “Post INF Great Power Arms Control.”

8. Gottemoeller, “U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Control Negotiations.”

9. Richard Weitz, “The Historical Context,” in Tactical Nuclear Weapons and NATO, ed. Tom Nichols, Douglas Stuart, and Jeffrey D. McCausland (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2012), p. 5.

10. Strobe Talbott, Deadly Gambits: The Reagan Administration and the Stalemate in Nuclear Arms Control (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1984), p. 42.

11. Maurer, “Post INF Great Power Arms Control.”

12. Ronald Reagan, “The MX: A Key to Arms Reduction,” The Washington Post, May 24, 1983.

Amy F. Woolf is a specialist in nuclear weapons policy at the Congressional Research Service (CRS). The views here are her own and are not necessarily shared by the CRS or the Library of Congress. A longer version of this article was originally commissioned by the American Nuclear Policy Commission, a project of Global Zero.

Now, at the 11th hour, they are pursuing an ill-advised strategy that has little chance of success and is probably designed to run out the clock on the last remaining treaty limiting the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals: the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

Now, at the 11th hour, they are pursuing an ill-advised strategy that has little chance of success and is probably designed to run out the clock on the last remaining treaty limiting the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals: the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

Arms control did not stop either nation from advancing its nuclear capabilities. Both replaced aging weapons systems, incorporated new technologies, and enhanced their ability to threaten the nuclear forces of the other nation. Neither saw a contradiction in the parallel efforts of negotiating limits while modernizing forces. To the contrary, many U.S. officials who have participated in the process

Arms control did not stop either nation from advancing its nuclear capabilities. Both replaced aging weapons systems, incorporated new technologies, and enhanced their ability to threaten the nuclear forces of the other nation. Neither saw a contradiction in the parallel efforts of negotiating limits while modernizing forces. To the contrary, many U.S. officials who have participated in the process The argument that the U.S. economy serves as a symbol of strength that should give pause to adversaries and point them to the negotiating table is also flawed. The U.S. gross domestic product may indicate that Washington has the resources to expand funding for military programs, but it is not clear that the U.S. electorate would support this expansion or that the military, if given access to added funds, would choose to direct them toward an expanded nuclear arsenal. Further, this argument does not allow space for debates about the relative cost of nuclear modernization programs and the possible need for trade-offs among competing priorities. It simply assumes that all spending is necessary and no programs should be curtailed until an agreement is complete.

The argument that the U.S. economy serves as a symbol of strength that should give pause to adversaries and point them to the negotiating table is also flawed. The U.S. gross domestic product may indicate that Washington has the resources to expand funding for military programs, but it is not clear that the U.S. electorate would support this expansion or that the military, if given access to added funds, would choose to direct them toward an expanded nuclear arsenal. Further, this argument does not allow space for debates about the relative cost of nuclear modernization programs and the possible need for trade-offs among competing priorities. It simply assumes that all spending is necessary and no programs should be curtailed until an agreement is complete. START II, however, also presents a clear case of how a treaty negotiated when one party is operating from a position of weakness can fail to achieve its expected goals. Russian officials immediately raised concerns about Russia’s financial and technical ability to maintain its forces at START II levels. The ban on multiple-warhead ICBMs would have cut deeply into the number of Russian ICBM warheads, and financial pressures would cut into Russia’s ballistic missile submarine force. At the same time, other U.S. policies and programs repeatedly reminded Russia of its position of weakness. NATO enlargement raised concerns in Russia about its relative position in Europe and the security situation near its borders. NATO engagement in Kosovo in 1999 reminded Russia of its reduced status in the international community. The United States continued to press forward with ballistic missile defense programs, and in 2002, when the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty, Russia officially withdrew from START II.

START II, however, also presents a clear case of how a treaty negotiated when one party is operating from a position of weakness can fail to achieve its expected goals. Russian officials immediately raised concerns about Russia’s financial and technical ability to maintain its forces at START II levels. The ban on multiple-warhead ICBMs would have cut deeply into the number of Russian ICBM warheads, and financial pressures would cut into Russia’s ballistic missile submarine force. At the same time, other U.S. policies and programs repeatedly reminded Russia of its position of weakness. NATO enlargement raised concerns in Russia about its relative position in Europe and the security situation near its borders. NATO engagement in Kosovo in 1999 reminded Russia of its reduced status in the international community. The United States continued to press forward with ballistic missile defense programs, and in 2002, when the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty, Russia officially withdrew from START II. Cluster munitions are defined in the CCM as “a conventional munition that is designed to disperse or release explosive submunitions each weighing less than 20 kilograms, and includes those explosive submunitions.” Because the convention aims to “end for all time the suffering and casualties caused by cluster munitions,” the definition focuses on those munitions shown to cause unacceptable and indiscriminate harm to civilians. Data collected by the Cluster Munition Monitor indicates that noncombatants have comprised more than 85 percent of all casualties from cluster munitions in the past decade.

Cluster munitions are defined in the CCM as “a conventional munition that is designed to disperse or release explosive submunitions each weighing less than 20 kilograms, and includes those explosive submunitions.” Because the convention aims to “end for all time the suffering and casualties caused by cluster munitions,” the definition focuses on those munitions shown to cause unacceptable and indiscriminate harm to civilians. Data collected by the Cluster Munition Monitor indicates that noncombatants have comprised more than 85 percent of all casualties from cluster munitions in the past decade. The impact of the convention’s norms has outpaced the convention’s universalization, with 144 states voting in favor—only Russia voted against—of the 2019 UN General Assembly resolution on CCM implementation, calling on states outside the convention to “join as soon as possible.” Allegations of cluster munitions use by states not party to the convention are met with passionate denial, indicating that international consensus on the stigma against cluster munitions is strong and growing in strength with each passing year.

The impact of the convention’s norms has outpaced the convention’s universalization, with 144 states voting in favor—only Russia voted against—of the 2019 UN General Assembly resolution on CCM implementation, calling on states outside the convention to “join as soon as possible.” Allegations of cluster munitions use by states not party to the convention are met with passionate denial, indicating that international consensus on the stigma against cluster munitions is strong and growing in strength with each passing year. The convention has set standards for international humanitarian law with regard to definitions of victims and the components of effective victim assistance, which have influenced other treaty bodies and negotiations. The norm against cluster munitions continues to grow, showing that international law works even in states outside the treaty. There are even stories of representatives from nonsignatories who have used cluster munitions asking civil society to stop drawing attention to their use of the banned weapons. They made those requests not because the allegations of use were false, but because the stigma against using such weapons was so high.

The convention has set standards for international humanitarian law with regard to definitions of victims and the components of effective victim assistance, which have influenced other treaty bodies and negotiations. The norm against cluster munitions continues to grow, showing that international law works even in states outside the treaty. There are even stories of representatives from nonsignatories who have used cluster munitions asking civil society to stop drawing attention to their use of the banned weapons. They made those requests not because the allegations of use were false, but because the stigma against using such weapons was so high. The German nuclear debate was triggered by a mid-April decision by the German Defense Ministry to replace its current fleet of Tornado dual-capable aircraft with 90 Eurofighter Typhoon and 45 U.S. F-18 fighter aircraft. Thirty of the F-18s would be certified to carry U.S. nuclear weapons.

The German nuclear debate was triggered by a mid-April decision by the German Defense Ministry to replace its current fleet of Tornado dual-capable aircraft with 90 Eurofighter Typhoon and 45 U.S. F-18 fighter aircraft. Thirty of the F-18s would be certified to carry U.S. nuclear weapons. Mützenich’s call for a debate on NATO nuclear sharing triggered predictable criticism. Proponents of the status quo argued that the security situation in Europe provides neither political nor military room for changing NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements. They also maintained that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Germany would undermine alliance solidarity. Some even argued that questioning nuclear sharing would hand Russian President Vladimir Putin a diplomatic victory. Others are concerned that Berlin would lose influence over NATO’s nuclear policies, should Germany give up its role as a host nation.

Mützenich’s call for a debate on NATO nuclear sharing triggered predictable criticism. Proponents of the status quo argued that the security situation in Europe provides neither political nor military room for changing NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements. They also maintained that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Germany would undermine alliance solidarity. Some even argued that questioning nuclear sharing would hand Russian President Vladimir Putin a diplomatic victory. Others are concerned that Berlin would lose influence over NATO’s nuclear policies, should Germany give up its role as a host nation.

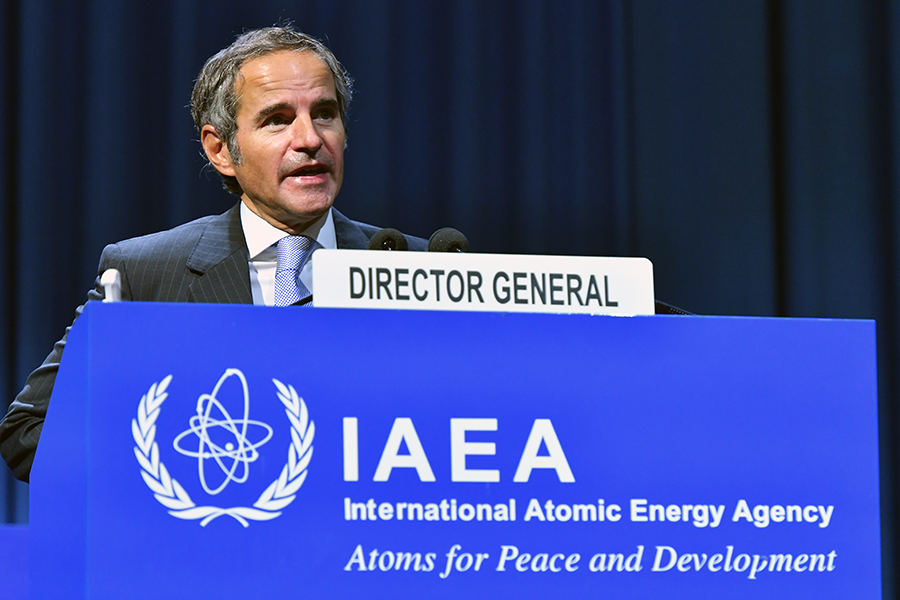

We spent several months in lockdown from March because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We were able to begin a phased return to the Vienna International Centre in May, but things are still far from normal, as is clear from the special arrangements made for this GC.

We spent several months in lockdown from March because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We were able to begin a phased return to the Vienna International Centre in May, but things are still far from normal, as is clear from the special arrangements made for this GC. UN sanctions on Iran were lifted or modified in 2016 as part of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the seven-party deal that limited Iran’s nuclear activities. Recently, the Trump administration asserted on Sept. 19 that the sanctions had been restored after the United States initiated a so-called snapback mechanism, created by UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which contains language allowing participants in the nuclear deal to reimpose UN sanctions in a manner that cannot be vetoed. The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 has created a dispute over U.S. standing to demand the return of UN sanctions under the terms of Resolution 2231.

UN sanctions on Iran were lifted or modified in 2016 as part of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the seven-party deal that limited Iran’s nuclear activities. Recently, the Trump administration asserted on Sept. 19 that the sanctions had been restored after the United States initiated a so-called snapback mechanism, created by UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which contains language allowing participants in the nuclear deal to reimpose UN sanctions in a manner that cannot be vetoed. The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 has created a dispute over U.S. standing to demand the return of UN sanctions under the terms of Resolution 2231. Moscow, which supports an unconditional five-year extension of the treaty, has called the U.S. proposal “absolutely unrealistic.” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said that “there are no grounds for any kind of deal in the form proposed” by Washington in a Sept. 21 interview with Kommersant. New START permits an extension of up to five years so long as the U.S. and Russian presidents agree.

Moscow, which supports an unconditional five-year extension of the treaty, has called the U.S. proposal “absolutely unrealistic.” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said that “there are no grounds for any kind of deal in the form proposed” by Washington in a Sept. 21 interview with Kommersant. New START permits an extension of up to five years so long as the U.S. and Russian presidents agree. “Now that we are out of the INF Treaty, the department is making rapid progress to field ground-launched missiles,” said Deputy Defense Secretary David Norquist on Sept. 10 at the Defense News Conference.

“Now that we are out of the INF Treaty, the department is making rapid progress to field ground-launched missiles,” said Deputy Defense Secretary David Norquist on Sept. 10 at the Defense News Conference.

Navalny was reportedly given the agent on Aug. 20 in Russia, where he received initial medical treatment before being flown to Germany, where doctors assessed that he had been exposed to the nerve agent Novichok, a substance banned under the CWC. The finding was corroborated by laboratories in France and Sweden, according to German government spokesman Steffen Seibert. He said on Sept. 14 that samples of the nerve agent detected in Navalny’s system were also sent to The Hague for additional tests at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the treaty’s implementing body. He called on Russia to “explain these events.”

Navalny was reportedly given the agent on Aug. 20 in Russia, where he received initial medical treatment before being flown to Germany, where doctors assessed that he had been exposed to the nerve agent Novichok, a substance banned under the CWC. The finding was corroborated by laboratories in France and Sweden, according to German government spokesman Steffen Seibert. He said on Sept. 14 that samples of the nerve agent detected in Navalny’s system were also sent to The Hague for additional tests at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the treaty’s implementing body. He called on Russia to “explain these events.” Although the agency notes that, without inspector access to North Korea’s nuclear facilities the IAEA “cannot confirm either the operational status or configuration/design features of the facilities or locations described,” the report suggests that North Korea’s production of fissile material, specifically of highly enriched uranium (HEU), continues. That the agency detected no indications of plutonium reprocessing would suggest that North Korea’s plutonium production has stalled.

Although the agency notes that, without inspector access to North Korea’s nuclear facilities the IAEA “cannot confirm either the operational status or configuration/design features of the facilities or locations described,” the report suggests that North Korea’s production of fissile material, specifically of highly enriched uranium (HEU), continues. That the agency detected no indications of plutonium reprocessing would suggest that North Korea’s plutonium production has stalled.