September 2020

In May 2018, the Trump administration announced the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed U.S. sanctions waived by the deal. One year later, Iran announced it would begin reducing its compliance with the JCPOA in response. This August, the Trump administration sought more stringent sanctions against Iran, and Iran agreed to enable International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors access to two controversial sites.

As the sanctions debate was unfolding at the United Nations and the IAEA Director General prepared to travel to Tehran, Arms Control Today discussed these and other nuclear issues on August 6 with Majid Takht Ravanchi, Iran’s permanent representative to the UN since April 2019. Prior to that, he served as deputy chief of staff for political affairs in the Iranian Office of the President beginning in 2017, and as deputy foreign minister for European and American affairs from 2013 to 2017. While serving as deputy foreign minister, Ravanchi participated in the multilateral negotiations on the JCPOA.

Arms Control Today: Iran announced in May 2019 that it would begin reducing compliance with limits imposed by the JCPOA in response to the deal’s failure to deliver on sanctions relief envisioned by the nuclear agreement after the United States. withdrew and re-imposed sanctions. In January 2020, Tehran announced that its nuclear program would no longer be subject to any limits. Does Iran intend to take any additional steps to breach its JCPOA obligations in the next several months? If so, what would be the intended purpose of those moves?

Arms Control Today: Iran announced in May 2019 that it would begin reducing compliance with limits imposed by the JCPOA in response to the deal’s failure to deliver on sanctions relief envisioned by the nuclear agreement after the United States. withdrew and re-imposed sanctions. In January 2020, Tehran announced that its nuclear program would no longer be subject to any limits. Does Iran intend to take any additional steps to breach its JCPOA obligations in the next several months? If so, what would be the intended purpose of those moves?

Amb. Majid Takht Ravanchi: The United States withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018 in contravention of its obligations under international law because the JCPOA is part of Resolution 2231. It is an annex to the resolution. The resolution has endorsed the JCPOA, and Resolution 2231 was adopted unanimously by the whole Security Council. So that shows that the whole international community was behind Resolution 2231.

The U.S. move was against international law and against the international obligations of the United States. After the U.S. withdrew from the JCPOA Iran waited for almost a year to see what the other members of the JCPOA could do in order to give Iran the benefits of the JCPOA. We were told by some members of the JCPOA that Iran would be compensated for the losses that it has received as a result of the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA. But unfortunately, after a year we did not receive any tangible benefits from implementing our obligations under the JCPOA. Then at that time in 2019, after a year, we were left with no other option but to reduce our commitments. This is in line with Articles 26 and 36 of the JCPOA, so our action is totally in line with our commitments in the JCPOA.

Regarding whether Iran is going to move further from what we have done, as you know after taking the fifth steps, Iran said it would no longer take any action, and that has been our position since. As far as our future action is concerned, it depends very much on the way that the JCPOA and Resolution 2231 are going to be treated. Our actions will be corresponding to whatever happens with Resolution 2231 and the JCPOA.

ACT: Until recently, Iran still benefited from cooperative nuclear projects in the JCPOA. However, in July, U.S. sanctions waivers for several activities required by the JCPOA, including modifications of the Arak reactor, were terminated. What is the status of the Arak conversion project? What are Iran’s plans for the future of the reactor?

Ravanchi: The U.S. move a few months ago was another act in contravention of U.S. obligations, as they put sanctions on the nuclear cooperation between Iran and other countries. So that is the basis of the U.S. decision to withdraw from the JCPOA. And then they started violating their obligations in May 2018. They just put aside the nuclear cooperation with other countries, and now they put the final nail in the way the JCPOA is being treated. So that shows the real intention of the United States when it really does not want Iran to have advancement in high technology, and that shows that the U.S. is not interested in seeing the Iranian people enjoy the benefits of scientific achievements. As far as the Arak nuclear facility is concerned, we are in talks with our partners, and the talks are ongoing. At the same time, we have said that if we are faced with a situation when Iran cannot advance this part of its nuclear facilities, we will go back to the old design, which was something of our creation. So that is an option for Iran, and we will decide at the right time when to go back to the old design. This is a very good option for Iran.

ACT: In July, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif announced that Tehran triggered the JCPOA’s dispute resolution mechanism (DRM) to address what Iran views as a violation of the deal by the France, Germany and the United Kingdom. What specifically does Iran hope to achieve with this move?

Ravanchi: That was not the first time that we initiated the DRM. In fact, since 2016 we have invoked the DRM mechanism on different occasions that the JCPOA was violated. The last time that we invoked the DRM was in response to lack of commitments by the EU partners. So this is a mechanism that every member of the JCPOA can apply, and we have used our rights in accordance with the JCPOA to benefit from the dividends that are supposed to be given to Iran. Our main purpose is to show that we have a complaint and the Joint Commission of the JCPOA has to study this complaint. We have sent our letter to the head of the EU Commission, and we hope that our concerns and our complaints will be taken into account by the Joint Commission.

ACT: The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) issued two reports in 2020 detailing its investigation into past, possible undeclared nuclear activities and materials and its unmet requests to inspect two facilities in Iran. After these reports were issued, the agency’s Board of Governors passed a resolution calling on Iran to cooperate with the agency’s inquiries. Iran told the agency in June it is “willing to satisfy the agency’s requests” but certain “legal ambiguities” must be addressed first. What are the specific legal ambiguities that Iran wants addressed and how?

Ravanchi: First of all, Iran has continuously cooperated with the IAEA. Just look at the figures the IAEA produces. In 2019 almost 20 percent of all inspections, all over the world, have been done in Iran. That figure shows by itself that Iran is cooperating with the IAEA, so inspectors can go and visit different places in Iran. To say Iran is called to cooperate is not really an interesting argument, because Iran is cooperating with the IAEA. As for those specific places that they wanted to see, we were discussing with IAEA people in Iran, in fact the deputy director-general was in Iran, and we were discussing the issue with him. And our talks were advancing, and all of a sudden we witnessed a move in the IAEA Board of Governors to issue a resolution against Iran. That was very counterproductive because we were about to resolve the issue of the visits.

We have said time and again that the IAEA is a technical body. It should not be politicized, but unfortunately some countries, headed by the United States, are politicizing this organization. We think that the best way to address the problem is to adhere to the technical nature of this body. We are in contact with the IAEA, we are in contact with members of the Board of Governors in Vienna, and we hope that we can resolve this issue.

There are certain principles that we need to adhere to. We cannot rely on fake information or fake intelligence to conduct the business of the IAEA. Information given to the agency by the Israeli regime cannot be relied on because they have been very adamant in providing fake information, particularly with regards to Iran. So that is something that needs to be considered by the agency. If the agency has its own evidence, it has to show its evidence to Iran, not just duplicating what it was given by others.

Another point is that we have already closed the “possible military dimensions” (PMD) file back in 2015. We cannot allow this file to open again because we have already closed that, and the agency has issued a resolution on this. The Board of Governors has already issued a resolution for the closure of PMD. And alleged activities going back to 17 years ago is not something that the Board of Governors should be spending time to issue a resolution on. So these are the politicized activities I was referring to. Therefore, we think that we should continue our talks with the agency and with the members of the Board of Governors so that we can find a solution to the problem.

ACT: As you know, the Trump administration is seeking to extend the UN restrictions on Iran’s conventional arms sale that are set to expire in October per Security Council Resolution 2231 and U.S. officials say they will use the snapback mechanism in that resolution if necessary. A number of countries, including those still party to the JCPOA, oppose U.S. efforts and disagree with the U.S. legal interpretation that it is still entitled to use snapback. How do you expect this debate will play out in the Security Council? How would Iran respond if the Council agrees to extend the arms embargo or if the United States tries and somehow succeeds in snapping back UN sanctions under UNSC 2231?

Ravanchi: First of all, any move by the security Council to impose sanctions, military sanctions against Iran, is illegal, is against Resolution 2231. So, there's no legal room for the adoption of any resolution by the security Council to impose sanctions on Iran. The second issue is that the U.S. attempt is going to fail because the members of the Security Council are not prepared to accept the violation of Resolution 2231. As I said before, 2231 was adopted by consensus, by unanimity, in the Security Council, and that is part of international law. So, members of the Security Council today should be the last ones to adopt something against international law.

As far as the snap-back is concerned, it is really a very ridiculous proposition to consider the United States as a JCPOA participant because the U.S. is not a member. It has already said that it ceased its participation in the JCPOA, and it said this at the highest level. Just look at the announcement by the White House on May 8, 2018. It says the U.S. has ceased participation in the JCPOA. And high officials in the United States government have said that they are not going to refer to the JCPOA because they are not members of the JCPOA. At times the U.S. officials claimed that JCPOA and Resolution 2231 are two separate documents. While the U.S. has withdrawn from the JCPOA, it still claims to be a member of 2231. Apparently, they have not read resolution 2231. Resolution 2231 endorses the JCPOA, and the JCPOA is an annex to Resolution 2231. We are not talking about two separate documents. We are talking about one document and that is resolution 2231.

As far as the snap-back is concerned, it is really a very ridiculous proposition to consider the United States as a JCPOA participant because the U.S. is not a member. It has already said that it ceased its participation in the JCPOA, and it said this at the highest level. Just look at the announcement by the White House on May 8, 2018. It says the U.S. has ceased participation in the JCPOA. And high officials in the United States government have said that they are not going to refer to the JCPOA because they are not members of the JCPOA. At times the U.S. officials claimed that JCPOA and Resolution 2231 are two separate documents. While the U.S. has withdrawn from the JCPOA, it still claims to be a member of 2231. Apparently, they have not read resolution 2231. Resolution 2231 endorses the JCPOA, and the JCPOA is an annex to Resolution 2231. We are not talking about two separate documents. We are talking about one document and that is resolution 2231.

Resolution 2231 talks about JCPOA participants. It is not talking about 2231 participants, it talks about JCPOA participants. There are certain rights and certain obligations for JCPOA participants. Because the U.S. has withdrawn from the JCPOA, it cannot be considered a JCPOA participant. So, there is no legal basis for the U.S. claim to be a JCPOA participant. We believe that the United States cannot invoke the relevant provision in 2231 for bringing back the old resolutions. We have said very clearly that if arms embargoes are going to be back against Iran, Iran’s reaction will be harsh. We have different options available to us, and we do not rule out any political options that are available to Iran

ACT: Iran maintains that it will return to compliance with the JCPOA, if other parties meet their obligations. Presidential candidate Joe Biden has said he would reenter the JCPOA. If Biden is elected, or if the Trump administration were to express interest in rejoining the JCPOA, how quickly could such a return to compliance be accomplished once and if both sides agree to such an approach? Would Iran be open to follow-on talks with Washington and other JCPOA parties regarding the future of Iran’s nuclear program and other issues of mutual concern? What is the range of issues would Iran be willing to discuss in such a scenario?

Ravanchi: First of all, we are not interested to involve ourselves in U.S. domestic politics, so it is for the American people to decide who the next president should be. What is important for Iran, and for other countries, is the respect for international agreements, international law, that should be provided for by the U.S. government. It doesn't matter if it’s a Republican government or a Democratic government in the White House, the U.S. obligations should be respected by all U.S. governments. So, Resolution 2231 is part of international law, and the U.S. government has a legal obligation to observe the provisions of Resolution 2231. If the next administration, whoever that might be, is going to accept Resolution 2231 and implement the provisions of the JCPOA in all honesty, I believe there is room for the United States to join the other members of the JCPOA within the context of the Joint Commission to talk about different issues related to the Iran deal. That is something that we have to wait and see whether the U.S. will take that decision or not.

Another point I also have to emphasize is that Iran has suffered a lot after the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA. In the last couple of years, we have suffered a lot in terms of losing precious Iranian lives as a result of the U.S. sanctions, even on food and medicine. We have lost a lot in terms of economic issues. So, there is a good argument by Iran to seek compensation from the United States. There are the things that have to be borne in mind when we were talking about future moves by the United States to join the JCPOA again.

ACT: The rescheduled 10th review conference of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is planned for early 2021 and many states believe that this is a key opportunity to reaffirm international support for the treaty and the full and timely implementation of its goals and objectives. Will Iran use this opportunity to reaffirm its commitment as an NPT state party to forswear nuclear weapons and to meet its NPT safeguards obligations?

Ravanchi: Iran was the first country back in 1974 to initiate a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly calling for the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East. Iran has also been observing its International obligations based on the NPT, so Iran is in good standing in terms of its respect for international law. We are going to have the opportunity in January 2021 to discuss different aspects of the NPT within the review mechanism. Definitely, Iran and other non-nuclear-weapon states will stress the fact that nuclear-weapon states have not been up to their obligations based on the relevant provision of the NPT.

Another point is in regard to the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zone and free from other weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East. As you know for the last couple of years, the UN General Assembly has been seized of this matter. Last year we had the first conference on this important issue. But unfortunately, Israel, with a known stockpile of nuclear warheads, has not shown any interest to join the effort to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East. I believe the next NPT review conference is also a good opportunity for all member states to call on the Israeli regime to join others in putting all of their unsafeguarded nuclear facilities under the supervision of the IAEA.

ACT: Back to the question of Iran’s approach to the 10th NPT Review Conference, do you plan to use this particular conference—an important one, the 10th review, 50 years after the treaty’s entry into force—to reaffirm Iran’s commitment to the NPT and all of its goals and to Iran’s future safeguards obligations. And on the zone issue, there will also be another meeting on the UN conference in November convened by the secretary-general. What specifically do you believe could and should be achieved at that November meeting and at the NPT review conference in the context of the objective of advancing the discussions toward the zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East?

ACT: Back to the question of Iran’s approach to the 10th NPT Review Conference, do you plan to use this particular conference—an important one, the 10th review, 50 years after the treaty’s entry into force—to reaffirm Iran’s commitment to the NPT and all of its goals and to Iran’s future safeguards obligations. And on the zone issue, there will also be another meeting on the UN conference in November convened by the secretary-general. What specifically do you believe could and should be achieved at that November meeting and at the NPT review conference in the context of the objective of advancing the discussions toward the zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East?

Ravanchi: On the first question, Iran’s position remains the same that there are certain obligations that nuclear-weapon-states have to honor. And the non-nuclear-weapon states are of the conviction that the nuclear-weapon-states have not observed their obligations. This is an important issue for non-nuclear-weapon states, and that issue will be brought up in the review conference. Regarding the nuclear-weapon-free zone, I believe that while we have a conference dealing specifically with this issue, we are of the opinion that the NPT review conference is also another avenue that should be considered to discuss this important issue because some countries were not eager to participate in or support the conference for the establishment of such a zone in the Middle East. Therefore, in the NPT review conference there is another opportunity for all members to discuss this important issue and try to support the establishment of such a zone and first and foremost to force the Israeli regime to accept joining others to discuss the establishment of such a zone in the Middle East.

ACT: Is it your expectation that the 10th review conference will still be taking place in January?

Ravanchi: It's too early to predict what exactly will happen in January. It depends on the situation at the time, because nobody can predict what the situation related to the pandemic is in January. If the situation is the same as what we had in March, I believe we can expect another postponement. But I suppose the way things are developing in New York City, I think and hope that the conference will convene as scheduled.

A closer examination of those assessments reveals that the bar for approval was not very high. Nearly all states in the region participated in the conference, 21 members of the Arab League and Iran; significantly, Israel chose to stay away. The discussion included general and thematic debates that allowed states to express their positions on core issues related to the zone, and the conference concluded by issuing a short political declaration. This is what success looks like for a process that has barely seen any progress since its inception in 1974. To sustain and grow the meeting’s momentum, the regional states that have committed to create a successful process to establish a WMD-free zone in the Middle East must agree first on the scope of such a treaty and securing the participation of all regional states.

A closer examination of those assessments reveals that the bar for approval was not very high. Nearly all states in the region participated in the conference, 21 members of the Arab League and Iran; significantly, Israel chose to stay away. The discussion included general and thematic debates that allowed states to express their positions on core issues related to the zone, and the conference concluded by issuing a short political declaration. This is what success looks like for a process that has barely seen any progress since its inception in 1974. To sustain and grow the meeting’s momentum, the regional states that have committed to create a successful process to establish a WMD-free zone in the Middle East must agree first on the scope of such a treaty and securing the participation of all regional states. Adding to the debate over which weapons would be prohibited in the zone is uncertainty over how these prohibitions would be implemented, including questions on how resulting obligations will be verified. Can verification be conducted by the existing three global nonproliferation and disarmament treaties, namely the NPT, Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and BWC? Will these need to be supplemented by additional, regional measures or by creating a unique regional regime?

Adding to the debate over which weapons would be prohibited in the zone is uncertainty over how these prohibitions would be implemented, including questions on how resulting obligations will be verified. Can verification be conducted by the existing three global nonproliferation and disarmament treaties, namely the NPT, Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and BWC? Will these need to be supplemented by additional, regional measures or by creating a unique regional regime? Five months later, armed conflicts continue to rage in Libya, Syria, Yemen, and other countries while insecurity persists on all continents. As the spread of the pandemic escalates and fighting continues, conventional arms, ammunition, and explosives continue to flow, sometimes in greater quantities, into conflict and other environments affected by armed violence. Conventional arms, in particular their availability and misuse, remain a common denominator in situations affected by the pandemic and armed conflicts.

Five months later, armed conflicts continue to rage in Libya, Syria, Yemen, and other countries while insecurity persists on all continents. As the spread of the pandemic escalates and fighting continues, conventional arms, ammunition, and explosives continue to flow, sometimes in greater quantities, into conflict and other environments affected by armed violence. Conventional arms, in particular their availability and misuse, remain a common denominator in situations affected by the pandemic and armed conflicts. Seizing this entry point is crucial for arms control. It provides a clear opportunity to establish the relevance and utility of arms control as an essential tool to address security and humanitarian risks arising in situations of armed conflict that are also affected by the pandemic. Conventional arms control measures could be monitored and reported by the UN and other relevant stakeholders in supporting the call for a global ceasefire.

Seizing this entry point is crucial for arms control. It provides a clear opportunity to establish the relevance and utility of arms control as an essential tool to address security and humanitarian risks arising in situations of armed conflict that are also affected by the pandemic. Conventional arms control measures could be monitored and reported by the UN and other relevant stakeholders in supporting the call for a global ceasefire.

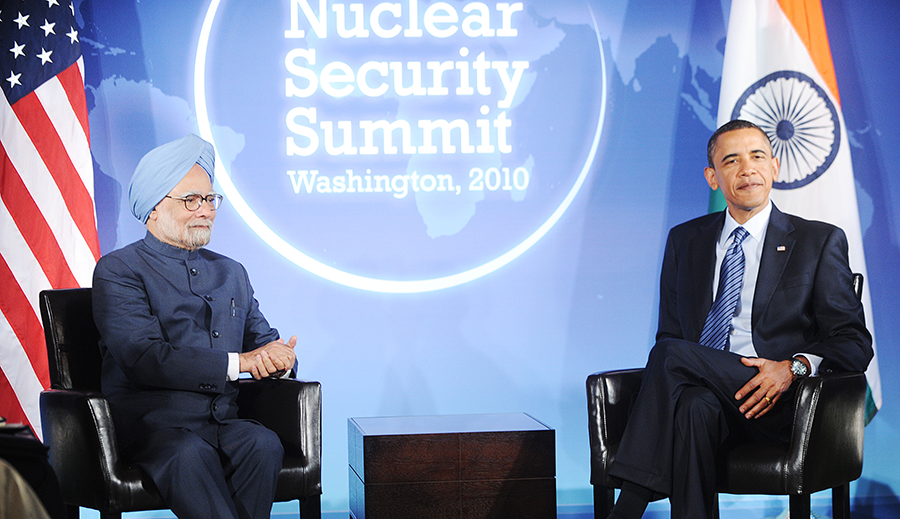

Initially, the summit process was narrowly conceived to address the risk of nuclear terrorism by persuading nations to secure vulnerable nuclear material in a period of four years. The idea was “to force the pace of change in the area of nuclear security by bringing international peer pressure and a whole-of-government approach to preventing nuclear terrorism,” Gill writes. During the process, however, other urgent issues emerged. For instance, the 2011 nuclear accident in Japan led the second summit to address the interface between nuclear safety and security. Subsequently, the agendas of the next two summits were expanded to embrace radiological material and orphan sources, as well as the cybersecurity of nuclear plants and facilities.

Initially, the summit process was narrowly conceived to address the risk of nuclear terrorism by persuading nations to secure vulnerable nuclear material in a period of four years. The idea was “to force the pace of change in the area of nuclear security by bringing international peer pressure and a whole-of-government approach to preventing nuclear terrorism,” Gill writes. During the process, however, other urgent issues emerged. For instance, the 2011 nuclear accident in Japan led the second summit to address the interface between nuclear safety and security. Subsequently, the agendas of the next two summits were expanded to embrace radiological material and orphan sources, as well as the cybersecurity of nuclear plants and facilities. I spent four formative years of my career with Global Zero, the international movement to eliminate nuclear weapons. In my work to rally the public behind our ambitious agenda, which was equal parts exhilarating and challenging, I had the honor and privilege to work with Bruce, Global Zero’s co-founder and inimitable leader.

I spent four formative years of my career with Global Zero, the international movement to eliminate nuclear weapons. In my work to rally the public behind our ambitious agenda, which was equal parts exhilarating and challenging, I had the honor and privilege to work with Bruce, Global Zero’s co-founder and inimitable leader. Iran threatened to take action if the Trump administration attempted to snap back UN sanctions, but Tehran might refrain from doing so after a number of council members, including the remaining parties to the nuclear deal, rejected the U.S. move as illegal.

Iran threatened to take action if the Trump administration attempted to snap back UN sanctions, but Tehran might refrain from doing so after a number of council members, including the remaining parties to the nuclear deal, rejected the U.S. move as illegal. Still, the administration continues to oppose an unconditional five-year extension of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and wants Moscow’s support for limiting all types of U.S. and Russian nuclear warheads and strengthening the New START verification regime as a condition for prolonging the treaty.

Still, the administration continues to oppose an unconditional five-year extension of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and wants Moscow’s support for limiting all types of U.S. and Russian nuclear warheads and strengthening the New START verification regime as a condition for prolonging the treaty. The UN report also details one member state’s independent conclusion that North Korea “may seek to further develop miniturisation in order to allow incorporation of technological improvements such as penetration aid packages or, potentially, to develop multiple warhead systems.”

The UN report also details one member state’s independent conclusion that North Korea “may seek to further develop miniturisation in order to allow incorporation of technological improvements such as penetration aid packages or, potentially, to develop multiple warhead systems.” “We do not feel any need to sit face to face with the U.S., as it does not consider the…dialogue as nothing more than a tool for grappling [with] its political crisis,” she added.

“We do not feel any need to sit face to face with the U.S., as it does not consider the…dialogue as nothing more than a tool for grappling [with] its political crisis,” she added.