September 2021

By Francesca Giovannini

This year marks a major milestone for the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO). The multilateral body was founded to support implementation and compliance with the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which established a prohibition on all nuclear weapons test explosions anywhere. After a protracted and combative election process against incumbent Lassina Zerbo, Australian candidate Rob Floyd prevailed with a convincing majority; and as of August 1, he has taken over as the CTBTO’s fourth executive secretary.

This change in leadership is expected to breathe new ideas into the management of the organization and could open new avenues for cooperation with countries in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. At the same time, Floyd and the organization face daunting challenges during a year that also marks the 25th anniversary of the CTBT’s opening for signature in 1996. Although the treaty has successfully halted nuclear testing for a quarter-century, the door to renewed testing and, with it, an accelerated expansion of global nuclear weapons capability remain open because the treaty has not yet formally entered into force.

This change in leadership is expected to breathe new ideas into the management of the organization and could open new avenues for cooperation with countries in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. At the same time, Floyd and the organization face daunting challenges during a year that also marks the 25th anniversary of the CTBT’s opening for signature in 1996. Although the treaty has successfully halted nuclear testing for a quarter-century, the door to renewed testing and, with it, an accelerated expansion of global nuclear weapons capability remain open because the treaty has not yet formally entered into force.

Despite political and legal uncertainty, the CTBTO and its member states have shown remarkable ingenuity in establishing a successful global monitoring network—the International Monitoring System (IMS)—of unprecedented scale and sophistication. The system relies on superb and still unsurpassed technical capabilities for monitoring and verifying the global nuclear test ban. Nevertheless, serious technical and political challenges to the long-term sustainability of the organization and the monitoring system are slowly emerging. Consequently, although this would be undesirable and politically costly, the international community should consider taking steps to decouple the IMS from the treaty’s fate in order to maintain and expand on the extraordinary technical investments that the monitoring system represents.

Indispensable but Ignored for Too Long

For 25 years, experts in academia and the nuclear policy community have written and argued about the CTBT’s indispensable role as an instrument for preventing nuclear proliferation, including the geographical spread of nuclear weapons to additional states and the qualitative improvement or expansion of existing nuclear weapons arsenals. Nuclear testing is crucial in the acquisition of nuclear weapons and in the improvement of such weapons.1 Because of the vital role played by the CTBT in nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, efforts to achieve its entry into force have gone in all directions, from public outreach initiatives to advocacy campaigns and youth mobilization. These laudable activities have helped to elevate the treaty’s visibility and involve a new generation of arms control scholars in the organization’s mission. Yet despite all efforts, the treaty remains in a legal vacuum.

One complication is the CTBT ratification process, which is unique and obtrusive. It requires ratification by 44 countries (the so-called Annex II states) that at the time of the negotiations were deemed nuclear capable. Today, eight of those countries—China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United States—have still failed to ratify the treaty and thus are preventing its entry into force.

Each of these countries faces distinct security challenges, operating within specific security dynamics marked by military, technological and ideological entanglements (table 1).

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, advocacy campaigns promoting the treaty’s entry into force focused mostly on building political coalitions within the U.S. Senate,2 moved by the untested but rational belief that ratification by the United States would incentivize other holdout countries to follow suit.3 That assumption might have sounded plausible then, but it appears far too simplistic today in a time of great-power competition, shifting regional loyalties, and a revival of a global arms race. Although U.S. ratification would very likely elicit positive support from other Annex II countries, it will not be sufficient to bring the treaty to the finish line.

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, advocacy campaigns promoting the treaty’s entry into force focused mostly on building political coalitions within the U.S. Senate,2 moved by the untested but rational belief that ratification by the United States would incentivize other holdout countries to follow suit.3 That assumption might have sounded plausible then, but it appears far too simplistic today in a time of great-power competition, shifting regional loyalties, and a revival of a global arms race. Although U.S. ratification would very likely elicit positive support from other Annex II countries, it will not be sufficient to bring the treaty to the finish line.

The uncertain destiny of the CTBT has reinforced the view among many non-nuclear-weapon states that incremental strategies to advance nuclear disarmament, such as the CTBT, will inevitably continue to be subjected to power procrastination games among nuclear-weapon states and will never be able to achieve a world without nuclear weapons.

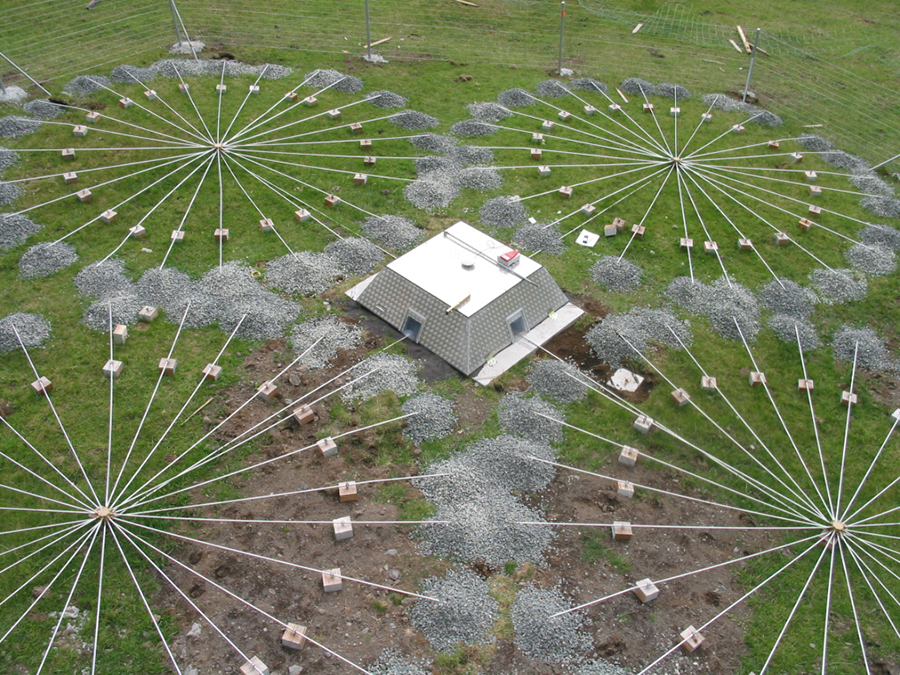

Other CTBT advocates counter that even though the CTBT has not formally entered into force, it has succeeded in bringing about a global nuclear testing halt, which is the central purpose of the treaty, on a de facto basis. They note that the only country that has clearly engaged in nuclear explosive testing in this century is North Korea, and for now, even that country has halted nuclear explosive testing. These advocates caution that the taboo against testing cannot be taken for granted and that, until such time as the CTBT enters into force, thus allowing for short-notice on-site inspections, or new confidence-building measures are established, concerns about clandestine nuclear test explosions, particularly at low yields, will linger.4

These narratives capture tangible fears and disillusionment among many countries squeezed between a new global arms race and the paralysis of multilateral arms control and disarmament institutions. They also reinforce a growing sense of doubt regarding the CTBT’s fate.

Another, not so visible yet equally important concern relates less to the treaty’s entry into force and more to the sustainability of the actual organization and the monitoring system it has created. As the treaty’s entry into force lags, critical questions surface. How long will the international community support the work of an organization operating in the absence of a legally binding treaty? How long will member countries pour resources into a monitoring system that, at best, will continue to operate provisionally for the foreseeable future? How long will the IMS remain capable of attracting top-notch scientific and technical talent?

The International Monitoring System

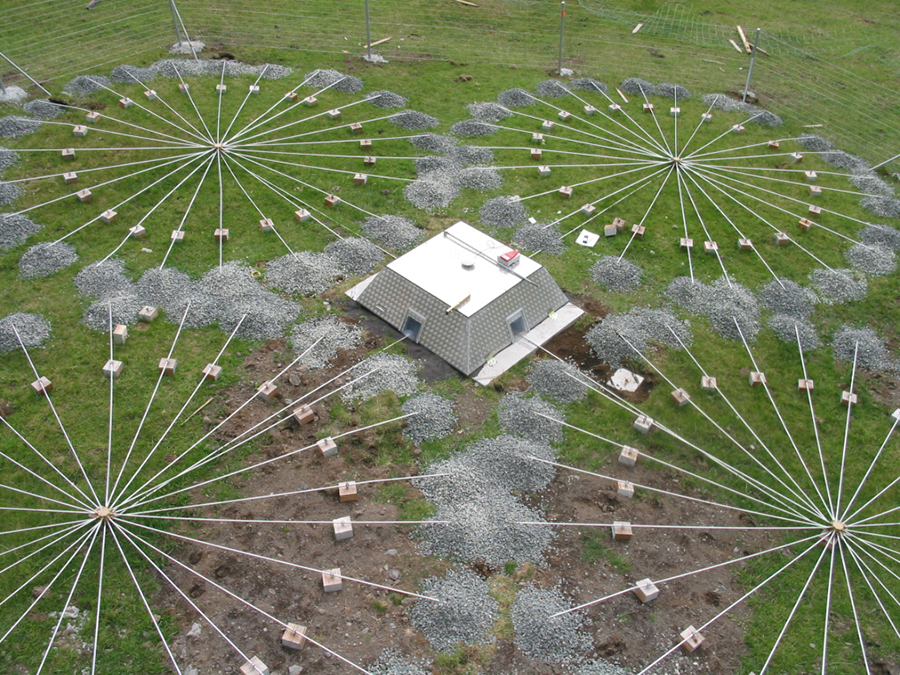

The IMS is an impressive and unmatched global monitoring system with features that make it a marvel of science diplomacy and international technological cooperation. It is the only global verification system concurrently employing four main technologies: radionuclide, which detects atmospheric nuclear explosions and determines the source of underwater and underground nuclear explosions; seismic, which detects underground explosions; hydroacoustic, which detects underwater explosions; and infrasound, which focuses on the atmosphere (table 2).

The need to adopt a multitude of technologies stemmed from the treaty’s broad mandate to ban all nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere, and in all environments—underground, underwater, and in the atmosphere. Most treaties are not so comprehensive.

The need to adopt a multitude of technologies stemmed from the treaty’s broad mandate to ban all nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere, and in all environments—underground, underwater, and in the atmosphere. Most treaties are not so comprehensive.

The work is carried out by a world-class scientific team of experts located in Vienna and at the CTBTO monitoring stations and technological hubs across Africa, Asia, South America, and beyond.

Although it is 92 percent complete, the system is operating on a provisional basis. That means that data originating from IMS operating stations are transmitted to the CTBTO’s Vienna headquarters through a satellite communications network. Once there, data is analyzed and screened by analysts with the CTBTO International Data Centre. Their findings are sent back to signatory states. Because of the provisional nature of the system, member states transmit the raw data on a voluntary basis. If suspicious activities are detected in the analysis of the data, members cannot make use of the treaty-enshrined follow-up mechanisms, such as consultations, clarification, and request for on-site inspections.

Regardless of its value, in the absence of a binding treaty, the provisional standing of the IMS raises important legal questions. As Masahiko Asada, professor of international law at Kyoto University, has remarked, “This presents a really unique situation in legal terms. Both the construction of the IMS network and its provisional operations have been carried out without the CTBT entry into force. What then is the legal basis for these developments?”5 For years, Article IV of the CTBT has been assumed to provide the authority for establishing the IMS in the absence of a legally binding treaty by stating that “[a]t the entry into force of this treaty, the verification regime shall be capable of being the verification requirements” of the CTBT.

This formulation allowed the organization to establish the IMS in preparation for the treaty’s entry into force. Construction began immediately, propelled by a sense of optimism that the treaty would enter into force without delay. After all, on September 24, 1996, the United States was the first nation to sign the CTBT. President Bill Clinton cast himself as an active promoter of the treaty, which he called “historic” and reflective of a “decades-old dream that no nuclear weapons will be detonated anywhere on the face of the earth.” At a time of U.S. economic and military supremacy, many believed that, despite significant political hurdles,6 CTBT ratification was within reach.

This formulation allowed the organization to establish the IMS in preparation for the treaty’s entry into force. Construction began immediately, propelled by a sense of optimism that the treaty would enter into force without delay. After all, on September 24, 1996, the United States was the first nation to sign the CTBT. President Bill Clinton cast himself as an active promoter of the treaty, which he called “historic” and reflective of a “decades-old dream that no nuclear weapons will be detonated anywhere on the face of the earth.” At a time of U.S. economic and military supremacy, many believed that, despite significant political hurdles,6 CTBT ratification was within reach.

To sustain momentum behind the ratification process, member states poured money into developing the IMS. By the time a nascent network of stations began to operate, however, the geopolitical landscape had changed dramatically. India and Pakistan conducted nuclear test explosions in 1998, the U.S. Senate rejected ratification in 1999, and the war in Kosovo had soured relations between Russia and the United States. Consequently, the build-up of the IMS slowed, but was never halted.

Two main drivers kept momentum going: First, many countries, including the United States, came to appreciate the value of the monitoring system as a provider of global data that national technical means could not match. Second, treaty supporters believed that by demonstrating the effectiveness of the system, negotiations on bringing the treaty into force would be revamped. As Zerbo remarked in 2016, “There is no better way to convince people to ratify the CTBT than showing them that they have a sustainable international monitoring system and the verification regime that can serve their purpose.”7

Despite its provisional status, the IMS has been consistently praised for exceeding expectations in detecting capabilities and enabling cross-domain scientific collaboration. The UN Security Council has officially recognized the effectiveness of the monitoring system and its role in enhancing peace and security by stating that “even absent entry into force of the treaty, the monitoring and analytical elements of the verification regime…contribute to regional stability as a significant confidence-building measure, and strengthen the nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament regime.”

In addition, the system has spurred enthusiasm for science and technology cooperation around the world and has democratized access to scientific data and know-how in unprecedented ways. Nations hosting IMS stations have concrete incentives to invest in their national scientific capacities to operate and maintain the stations and to benefit from the data. From Africa to Asia, a new global scientific community has emerged largely because of the IMS and the extensive investments by CTBTO in capacity building to sustain and expand the pool of scientific talent.

The IMS also represents a towering achievement in the democratization of science. As then-CTBTO Executive Secretary Tibor Tóth noted,

[T]he CTBT verification regime is a truly democratic and participatory system. The data and products of the CTBTO Preparatory Commission are made available to every signatory state, regardless of size or wealth or technological prowess, making sure that transparency is not limited to the few states who possess the necessary technical and financial resources. The credibility of our verification system does not only reside in its technical performance but also in the open and equal access of all signatory states.8

Challenges Facing the IMS

Although the capabilities of the IMS are often publicly praised, its emerging challenges are discussed in closed-door meetings among diplomats concerned about the future of the treaty and the organization. Like any technological system, to remain effective the IMS needs to attract and retain scientific talent, identify emerging technologies that could hinder or strengthen its operational capabilities, and attract the necessary resources to keep functioning even if only on a provisional basis.

These challenges would be complex to manage and address for any technological system, but the enduring legal limbo of the treaty could fatally undermine the ability to address these inherent vulnerabilities.

The race to secure scientific talent, for instance, is accelerating in all technical domains and across all continents. It is made more difficult by the rise in technonationalism and the pursuit of primacy and domination in strategic sectors, including artificial intelligence and space. Unsurprisingly, given the level of specialization required, the CTBTO has struggled to fill key technical positions and retain highly qualified experts as several national delegations have apprehensively noted.

As Mitsuru Kitano, Japan’s ambassador to the CTBTO, remarked, “[W]e appreciate the Provisional Technical Secretariat’s [PTS] continuous efforts to improve the system of recruitment. At the same time, we are concerned about the fact that there is still the issue of vacancies. It is essential to fill the vacancies as early as possible to provide a sound basis for a sustainable working environment for the organization to fulfil its mandate. We hope that the PTS will take appropriate measures to improve the situation.”9

Namibia’s Simon Madjumo Maruta, the representative of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), further underscored that the NAM, “while recognizing the difficulties faced by the PTS, reiterates its principled position that striving for equitable geographic distribution as well as gender balance in the overall composition of the PTS is of utmost importance. The [NAM] is encouraged by the renewed impulse given by the Executive Secretary to addressing the Human Resources issues that have been outstanding these past years.”10

There is also the threat of the IMS losing its technological edge. Because the treaty text is concluded but not entered into force, no technical changes or modifications can be made to the IMS design at this stage, including the adoption of new technologies that could make operating the system smarter and more cost effective. Meanwhile, national technical means continue to evolve and mature, potentially overtaking the IMS and making it redundant. For example, at the time of the treaty negotiations, satellite technology was deemed too costly and therefore not listed among IMS technologies. Today, the commercial satellite industry is flourishing, making the technology not only viable and accessible but ubiquitous and extraordinarily cheap. Nuclear expert George Perkovich once noted that the costs of verifying the transition to a world free of nuclear weapons would be substantial, exceeding initial forecasts. That is also proving true with the CTBTO. In fact, according to CTBTO sources, the costs incurred to build and run the IMS nears $1 billion, far exceeding initial estimates of roughly $80 million.

Most importantly, although initial investments to build the IMS might not have been especially high the costs of maintenance remain largely underestimated or, worse, unbudgeted. Building IMS stations around the world initially generated much enthusiasm, political visibility, and media attention. Yet, these stations need to be maintained and repaired, and the political fanfare that once accompanied their construction has waned. That is because it is relatively easier to sell something new than to convince domestic constituencies of the continued value of spending money to underwrite a treaty that has no viable prospects of entering into force soon.

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation, making it imperative for countries to be more frugal about their own investments. As a result, negotiations to secure the funding to repair and maintain operating stations are becoming difficult and compromises more difficult to reach. In the most recent CTBT report, Zerbo encouraged CTBTO member-states to embrace “a holistic approach to establish and sustain the complex global network of the IMS. This is achieved through testing, evaluating, and sustaining what is in place and then further improving on this. Sustainment covers maintenance through necessary preventive maintenance, repairs, replacement, upgrades, and continuous improvements to ensure the technological relevance of the monitoring capabilities.”11

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation, making it imperative for countries to be more frugal about their own investments. As a result, negotiations to secure the funding to repair and maintain operating stations are becoming difficult and compromises more difficult to reach. In the most recent CTBT report, Zerbo encouraged CTBTO member-states to embrace “a holistic approach to establish and sustain the complex global network of the IMS. This is achieved through testing, evaluating, and sustaining what is in place and then further improving on this. Sustainment covers maintenance through necessary preventive maintenance, repairs, replacement, upgrades, and continuous improvements to ensure the technological relevance of the monitoring capabilities.”11

Decoupling the IMS From the Treaty

Throughout the past decade, as the prospect for the treaty’s entry into force became more remote, proposals emerged to shake up the status quo and revive the political process. All of them are incomplete, possibly implausible, and unquestionably suboptimal, betraying the ultimate spirit that inspired the international community to negotiate the CTBT. Nonetheless, these ideas reveal a sense of urgency and pragmatism as CTBT proponents desperately seek to prevent institutional paralysis from turning into institutional collapse and a multilateral crisis.

A few of the proposals have sought ways to bypass the cumbersome ratification process. In an excellent analysis on the prospects for rescuing the treaty, John Carlson, former director-general of the Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office, suggests four possible paths. They are: negotiate a new treaty, replicate the existing CTBT but with revised entry-into-force provisions, waive Annex II by adopting a protocol or a resolution by which ratifying states declare the CTBT is in force and waive the Annex II provision, or agree to have part of the CTBT enter into force provisionally, for instance, some technical and verification measures, pending the ratification by all Annex II states.12

These options have been rejected by powerful states, including the Russian Federation and the NAM members, because they fundamentally undermine the “comprehensive nature” of the CTBT by failing to bind nuclear-weapon states that do not join the treaty. Such options would thus perpetuate power asymmetries and the unfair bargain between the nuclear haves and the nuclear have-nots.

As the situation continues to stagnate, another approach that focuses more narrowly on the survivability of the monitoring system deserves consideration. Until the treaty enters into force, the IMS could be decoupled from the treaty and established as a separate international body, namely an independent, international observatory on nuclear testing, committed to certain specific principles. One principle would be neutrality in data collection and delivery of the analysis. The other principle would be inclusive, international representation with governmental institutions and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) involved in securing the necessary technical and human resources.

Observatories have historical roots dating to 16th century Europe. They have traditionally been spaces of science and technology discoveries but also avenues for public engagement and social dialogue.

There are several advantages to this approach. It would allow more flexibility in introducing and adopting new technologies and enable the observatory to remain abreast of technical changes in nuclear verification. It would foster greater collaboration and elicit more direct involvement by academia, the private sector, and NGOs. It would promote data sharing among scientific institutions and would elevate further the importance of the IMS as a global hub for scientific and technological advancements in nuclear test verification. Finally, it would continue to serve as a technical avenue for cooperation among nuclear-weapon states invested in the establishment and maintenance of the IMS.

There is no question that such a proposal is at best suboptimal and at worst risky and undesirable. Decoupling the IMS from the treaty could undermine its symbolic and political standing vis-à-vis many of the countries that invested in the treaty in the first place. It also could set a dangerous precedent. Ratified treaties are a fundamental pillar of the modern, rule-based global order. Shifting to an easier yet less permanent cooperative mechanism could bring further instability and opportunism to an already unpredictable international environment. Finally, the proposal could turn into an observatory for rich nations only, thus further losing the universality that the treaty aspires to achieve.

Yet, the trade-offs that the international community might soon be forced to face between a treaty in limbo and a fully operational monitoring system capture a broader and more worrisome trend. In the face of growing global competition, achieving the entry into force of universal treaties will become increasingly difficult and unlikely. Hence, regional and global nuclear cooperation will have to take different forms from the ones they have taken in the past. Compromises will have to be made and suboptimal solutions, however distasteful and imperfect, will have to be accepted.

As the international community considers its options for defending, strengthening, and sustaining the CTBT regime, pressure is certain to build from those who argue that the treaty is not going anywhere and that no major initiatives are needed to secure its entry into force. Given that the CTBTO has matured into an effective operation over the past 25 years, the world will be able to muddle through uncertain times for another quarter of a century, or so that argument goes. That risky approach assumes member states will somehow continue to have the political will to stick with this treaty to a fading finish line. It also ignores the likelihood that new priorities will arise, that emergencies will take precedence, and that political support for the CTBT and financial support for the effective operation of the IMS will dwindle.

No path will be pain free. The international community is operating in a difficult period in which pragmatism should prevail and investments must be protected. For those who have been working on the CTBT for years, this observatory proposal might not be welcome, but the available alternatives could be much worse.

ENDNOTES

1. Sergio Duarte, “The Future of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test Ban Treaty,” UN Chronicle, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/future-comprehensive-nuclear-test-ban-treaty.

2. Daryl G. Kimball, “Learning From the 1999 Vote on the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty,” Arms Control Today, October 2009, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2009-10/learning-1999-vote-nuclear-test-ban-treaty.

3. Rizwan Asghar, “The Future of the CTBT,” CTBTO Spectrum, No. 22 (August 2014), p. 17,

https://www.ctbto.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/Spectrum/2014/Spectrum_22_web.pdf.

4. Daryl G. Kimball, “U.S. Claims of Illegal Russian Nuclear Testing: Myths, Realities, and Next Steps,” Arms Control Association Policy White Paper, August 16, 2019, https://www.armscontrol.org/sites/default/files/files/PolicyPapers/ACA_PolicyPaper_CTBT_DK_2019.pdf.

5. Masahiko Asada, “CTBT: Legal Questions Arising From Its Non-entry Into Force,” Journal of Conflict and Security Law, Vol. 7, No. 1 (April 2002): 104.

6. Barbara Crossette, “UN Endorses a Treaty to Halt All Nuclear Testing,” The New York Times, September 11, 1996, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/11/world/un-endorses-a-treaty-to-halt-all-nuclear-testing.html.

7. Andreas Persbo, “Compliance Science: The CTBT Global Verification System,” Non-Proliferation Review, Vol. 23, Nos. 3-4 (2016): 1.

8. “Statement of the Executive Secretary, Mr. Tibor Tóth, on the Occasion of the Scientific Symposium,” August 31, 2006, https://www.ctbto.org/fileadmin/content/reference/symposiums/2006/0831tothspeech.pdf.

9. Mitsuru Kitano, statement at the 45th session of the CTBTO, November 16, 2015, https://www.vie-mission.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/PC45_statement_EN.html.

10. Simon Madjumo Maruta, statement on behalf of the Group of 77 and China at the 46th session of the CTBTO, June 14, 2016, https://www.g77.org/vienna/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CTBTOMatters_46th-Session-of-the-CTBTO-PrepCom-13-17-June-2016.pdf.

11. Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), “Advancing Verification Capabilities: Annual Report 2019,” September 2020, p. 12, https://www.ctbto.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/Annual_Report_2019/English/00-CTBTO_AR_2019_EN.pdf.

12. John Carlson, “Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty: Possible Measures to Bring the Provisions of the Treaty into Force and Strengthen the Norm Against Nuclear Testing”, VCDNP, March 2019, https://vcdnp.org/ctbt-possible-measures-to-bring-the-provisions-of-the-treaty-into-force-strengthen-the-norm-against-nuclear-testing/

Francesca Giovannini is the executive director of the Harvard Belfer’s Initiative on Managing the Atom and the research director of the Nuclear Deterrence Research Network funded by the MacArthur Foundation. She is an adjunct associate professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Prior to her Harvard appointment, she served as strategy and policy officer to the executive secretary of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), based in Vienna. In that capacity, she oversaw a series of policy initiatives to promote CTBT ratification as a confidence-building mechanism in regional and bilateral nuclear negotiations.

Nuclear testing also produced radioactive contamination, not only immediately downwind from the test sites but globally. One independent study from 1991 estimates that nuclear testing led to nearly half a million additional cancer fatalities worldwide through the year 2000.

Nuclear testing also produced radioactive contamination, not only immediately downwind from the test sites but globally. One independent study from 1991 estimates that nuclear testing led to nearly half a million additional cancer fatalities worldwide through the year 2000.

This change in leadership is expected to breathe new ideas into the management of the organization and could open new avenues for cooperation with countries in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. At the same time, Floyd and the organization face daunting challenges during a year that also marks the 25th anniversary of the CTBT’s opening for signature in 1996. Although the treaty has successfully halted nuclear testing for a quarter-century, the door to renewed testing and, with it, an accelerated expansion of global nuclear weapons capability remain open because the treaty has not yet formally entered into force.

This change in leadership is expected to breathe new ideas into the management of the organization and could open new avenues for cooperation with countries in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. At the same time, Floyd and the organization face daunting challenges during a year that also marks the 25th anniversary of the CTBT’s opening for signature in 1996. Although the treaty has successfully halted nuclear testing for a quarter-century, the door to renewed testing and, with it, an accelerated expansion of global nuclear weapons capability remain open because the treaty has not yet formally entered into force. Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, advocacy campaigns promoting the treaty’s entry into force focused mostly on building political coalitions within the U.S. Senate,

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, advocacy campaigns promoting the treaty’s entry into force focused mostly on building political coalitions within the U.S. Senate, The need to adopt a multitude of technologies stemmed from the treaty’s broad mandate to ban all nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere, and in all environments—underground, underwater, and in the atmosphere. Most treaties are not so comprehensive.

The need to adopt a multitude of technologies stemmed from the treaty’s broad mandate to ban all nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere, and in all environments—underground, underwater, and in the atmosphere. Most treaties are not so comprehensive. This formulation allowed the organization to establish the IMS in preparation for the treaty’s entry into force. Construction began immediately, propelled by a sense of optimism that the treaty would enter into force without delay. After all, on September 24, 1996, the United States was the first nation to sign the CTBT. President Bill Clinton cast himself as an active promoter of the treaty, which he called “historic” and reflective of a “decades-old dream that no nuclear weapons will be detonated anywhere on the face of the earth.” At a time of U.S. economic and military supremacy, many believed that, despite significant political hurdles,

This formulation allowed the organization to establish the IMS in preparation for the treaty’s entry into force. Construction began immediately, propelled by a sense of optimism that the treaty would enter into force without delay. After all, on September 24, 1996, the United States was the first nation to sign the CTBT. President Bill Clinton cast himself as an active promoter of the treaty, which he called “historic” and reflective of a “decades-old dream that no nuclear weapons will be detonated anywhere on the face of the earth.” At a time of U.S. economic and military supremacy, many believed that, despite significant political hurdles, The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation, making it imperative for countries to be more frugal about their own investments. As a result, negotiations to secure the funding to repair and maintain operating stations are becoming difficult and compromises more difficult to reach. In the most recent CTBT report, Zerbo encouraged CTBTO member-states to embrace “a holistic approach to establish and sustain the complex global network of the IMS. This is achieved through testing, evaluating, and sustaining what is in place and then further improving on this. Sustainment covers maintenance through necessary preventive maintenance, repairs, replacement, upgrades, and continuous improvements to ensure the technological relevance of the monitoring capabilities.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation, making it imperative for countries to be more frugal about their own investments. As a result, negotiations to secure the funding to repair and maintain operating stations are becoming difficult and compromises more difficult to reach. In the most recent CTBT report, Zerbo encouraged CTBTO member-states to embrace “a holistic approach to establish and sustain the complex global network of the IMS. This is achieved through testing, evaluating, and sustaining what is in place and then further improving on this. Sustainment covers maintenance through necessary preventive maintenance, repairs, replacement, upgrades, and continuous improvements to ensure the technological relevance of the monitoring capabilities.”

Pyongyang has never submitted to intrusive verification and monitoring of its missile capabilities and missile-related industrial complex, so whatever the form of future negotiations, this issue is sure to be contentious. Even so, missile freeze agreements could take various forms, with implications for how they might be verified.

Pyongyang has never submitted to intrusive verification and monitoring of its missile capabilities and missile-related industrial complex, so whatever the form of future negotiations, this issue is sure to be contentious. Even so, missile freeze agreements could take various forms, with implications for how they might be verified. This piecemeal approach to safeguards need not preclude the IAEA’s eventual return to traditional verification and monitoring activities in North Korea. To the contrary, such an approach would be central to the final goal of complete denuclearization. Despite its lack of a presence in North Korea since 2009, the IAEA has continued to use open sources and a variety of analytical techniques to maintain its readiness for an eventual return to the country.

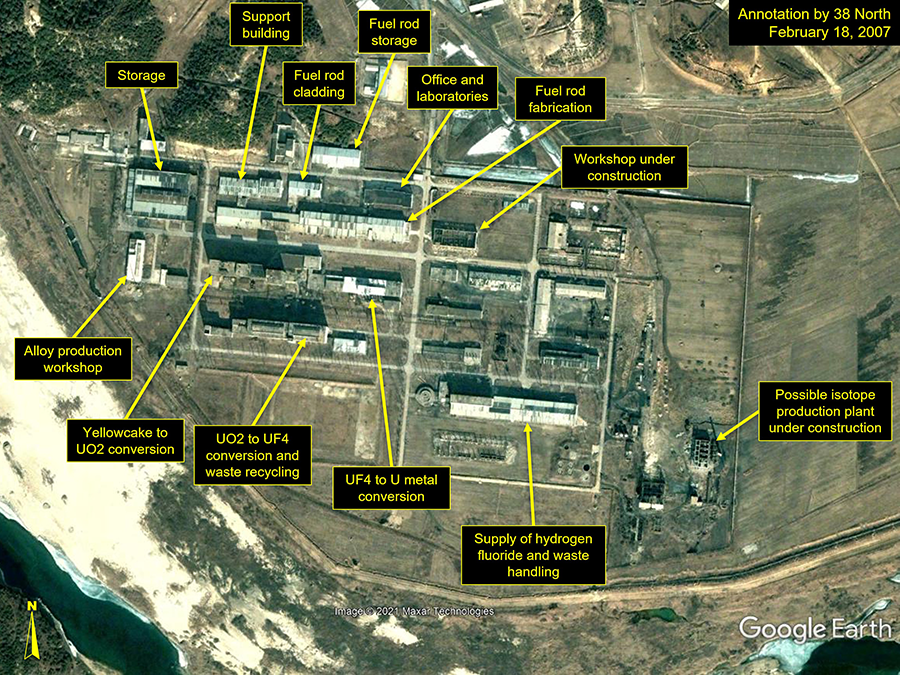

This piecemeal approach to safeguards need not preclude the IAEA’s eventual return to traditional verification and monitoring activities in North Korea. To the contrary, such an approach would be central to the final goal of complete denuclearization. Despite its lack of a presence in North Korea since 2009, the IAEA has continued to use open sources and a variety of analytical techniques to maintain its readiness for an eventual return to the country. When the CWC entered into force in 1997, it seemed that all that remained to achieve a world free of chemical weapons was to verifiably destroy declared stockpiles and universalize membership. Instead, the international norm against chemical weapons use is under siege, most prominently by Syria and Russia, two states-parties to that very treaty. The world is now precariously perched on the knife’s edge of a new era of chemical weapons use.

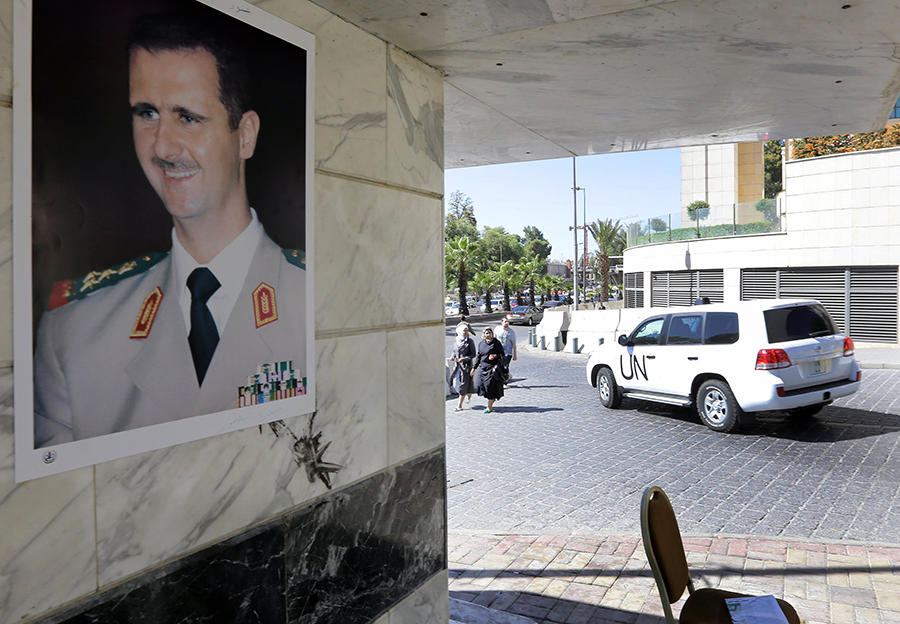

When the CWC entered into force in 1997, it seemed that all that remained to achieve a world free of chemical weapons was to verifiably destroy declared stockpiles and universalize membership. Instead, the international norm against chemical weapons use is under siege, most prominently by Syria and Russia, two states-parties to that very treaty. The world is now precariously perched on the knife’s edge of a new era of chemical weapons use. As the chemical weapons threat widened to the European continent, the crisis in Syria deepened. On April 7, multiple chlorine-filled barrel bombs were dropped on the Damascus suburb of Douma, killing dozens of civilians. Again, a highly charged special meeting of the OPCW Executive Council was convened on April 16, just two days after joint military strikes against Syrian government facilities by France, the UK, and United States. Russia and Syria falsely claimed that the UK and the United States “staged” the Douma chlorine attacks with the help of the White Helmets, an organization of volunteer first responders in Syria that Russia has tried to label as terrorists. Within weeks, OPCW fact finders went to Douma to further its investigation, which ultimately concluded that chlorine was used.

As the chemical weapons threat widened to the European continent, the crisis in Syria deepened. On April 7, multiple chlorine-filled barrel bombs were dropped on the Damascus suburb of Douma, killing dozens of civilians. Again, a highly charged special meeting of the OPCW Executive Council was convened on April 16, just two days after joint military strikes against Syrian government facilities by France, the UK, and United States. Russia and Syria falsely claimed that the UK and the United States “staged” the Douma chlorine attacks with the help of the White Helmets, an organization of volunteer first responders in Syria that Russia has tried to label as terrorists. Within weeks, OPCW fact finders went to Douma to further its investigation, which ultimately concluded that chlorine was used.

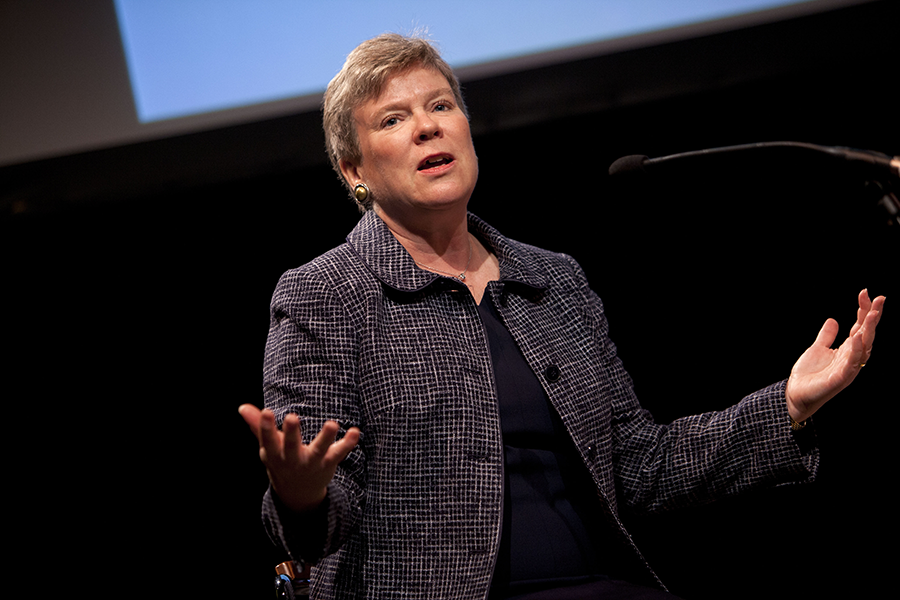

Backstopping requires a unique leadership style. The leader must be able to bring about consensus, if possible; recognize when consensus is unlikely; and work to gain an appropriate decision to allow instructions to proceed. Gottemoeller recounts how well the process that supported her worked, largely because of the experience and skill of the chair of the backstopping committee, Lynn Rusten.

Backstopping requires a unique leadership style. The leader must be able to bring about consensus, if possible; recognize when consensus is unlikely; and work to gain an appropriate decision to allow instructions to proceed. Gottemoeller recounts how well the process that supported her worked, largely because of the experience and skill of the chair of the backstopping committee, Lynn Rusten. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressed his concern with the “rapid growth” of China’s nuclear arsenal at an Aug. 6 meeting of foreign ministers at the ASEAN Regional Forum. He said this dramatic expansion indicates a sharp deviation from Beijing’s “decades-old nuclear strategy based on minimum deterrence,” according to a readout of the meeting by State Department spokesman Ned Price.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressed his concern with the “rapid growth” of China’s nuclear arsenal at an Aug. 6 meeting of foreign ministers at the ASEAN Regional Forum. He said this dramatic expansion indicates a sharp deviation from Beijing’s “decades-old nuclear strategy based on minimum deterrence,” according to a readout of the meeting by State Department spokesman Ned Price. “The Nuclear Posture Review [NPR] is currently underway,” Lt. Col. Uriah Orland, a Defense Department spokesman, told Arms Control Today on Aug. 13. “The review started in early July, and it will be finalized in conjunction with the National Defense Strategy early next year.”

“The Nuclear Posture Review [NPR] is currently underway,” Lt. Col. Uriah Orland, a Defense Department spokesman, told Arms Control Today on Aug. 13. “The review started in early July, and it will be finalized in conjunction with the National Defense Strategy early next year.” Prior to Raisi’s election in June, the United States and Iran participated in six rounds of indirect talks in Vienna to hash out the steps that each side would need to take to return to compliance with the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The European Union coordinated the negotiations on behalf of the other parties to the deal—China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom.

Prior to Raisi’s election in June, the United States and Iran participated in six rounds of indirect talks in Vienna to hash out the steps that each side would need to take to return to compliance with the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The European Union coordinated the negotiations on behalf of the other parties to the deal—China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom. U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to relaunch a bilateral strategic stability dialogue during their June summit, and delegations representing Washington and Moscow held their first meeting in Geneva on July 28. (See

U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to relaunch a bilateral strategic stability dialogue during their June summit, and delegations representing Washington and Moscow held their first meeting in Geneva on July 28. (See  The U.S. delegation was led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Bonnie Jenkins, the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security. The U.S. team included officials from the National Security Council and the Defense, Energy, and State departments. Ryabkov led the Russian delegation.

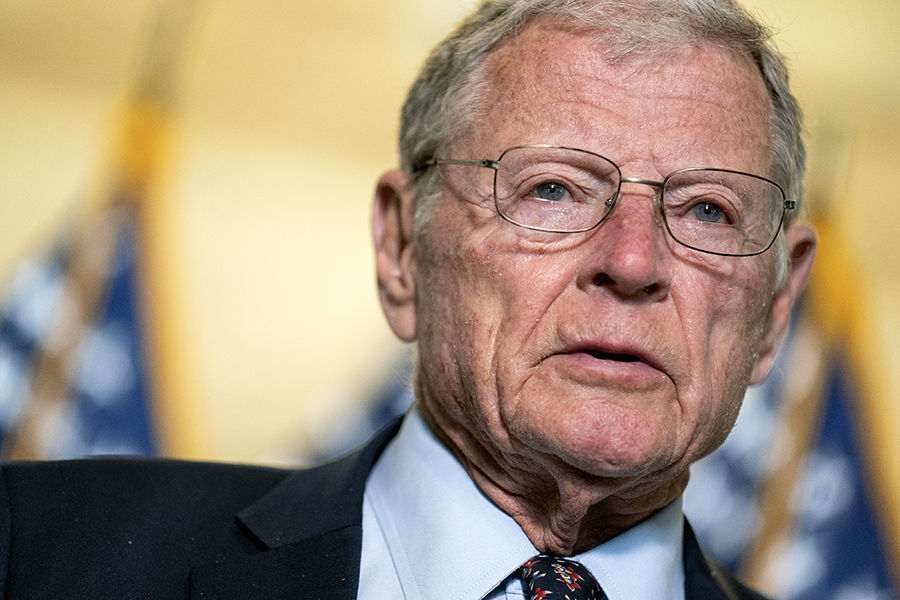

The U.S. delegation was led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Bonnie Jenkins, the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security. The U.S. team included officials from the National Security Council and the Defense, Energy, and State departments. Ryabkov led the Russian delegation. But the council also warned that the request “injects risk into the longer-term schedule required to ensure modernization of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

But the council also warned that the request “injects risk into the longer-term schedule required to ensure modernization of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”