October 2016

By Frank Sauer

Autonomous weapons systems have drawn widespread media attention, particularly since last year’s open letter signed by more than 3,000 artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics researchers warning against an impending “military AI arms race.”1

Since 2013, discussion of such weapons has been climbing the arms control agenda of the United Nations. They are a topic at the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly First Committee on disarmament and international security, but the main venue of the debate is the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) in Geneva.2 So far, CCW countries have convened for three informal meetings of experts on the topic and in December will decide whether to continue and deepen their deliberations by establishing a group of governmental experts next year.

Stigmatized as “killer robots” by opponents, autonomous weapons systems are widely regarded as harbingers of a paradigm shift in warfare. As described in a 2012 Pentagon document,3 “[Once] activated, [they] can seek, select and engage targets without intervention by a human operator.” In other words, these weapons would be able to make decisions on the use of lethal force without a human in the decision-making loop. The directive says such systems should allow for “appropriate levels of human judgment” over the use of lethal force, leaving open the question of what constitutes “appropriate.”

Stigmatized as “killer robots” by opponents, autonomous weapons systems are widely regarded as harbingers of a paradigm shift in warfare. As described in a 2012 Pentagon document,3 “[Once] activated, [they] can seek, select and engage targets without intervention by a human operator.” In other words, these weapons would be able to make decisions on the use of lethal force without a human in the decision-making loop. The directive says such systems should allow for “appropriate levels of human judgment” over the use of lethal force, leaving open the question of what constitutes “appropriate.”

So far, only precursor systems and technology demonstrators exist. This makes autonomous weapons systems a candidate for preventive arms control.

This article clarifies what autonomous weapons systems are and lists the driving forces behind the push toward weapons autonomy. It reviews the resulting problems that render this technology a hotly debated arms control issue. After the CCW landscape has been charted, the article concludes by identifying four possible outcomes of the CCW process and pondering future arms control perspectives and policy recommendations.

The Basics

Some weapons systems used for defensive purposes already can identify and track incoming targets and engage them without a human pushing the metaphorical button. Deemed precursors to autonomous weapons systems, they can react to incoming missiles or mortar shells in cases in which the timing does not allow for human decision-making. The Phalanx Close-In Weapon System on Navy ships is one example for such a weapons system, Israel’s Iron Dome air defense system is another.

Yet, these defensive systems are not the focus of the mainly forward-looking autonomous weapons systems debate. Juxtaposing automatic and autonomous systems is a helpful way to understand why. Defensive systems such as the Phalanx can be categorized as automatic. They are stationary or fixed on ships or trailers and designed to fire at inanimate targets. They just repeatedly perform preprogrammed actions and operate only within tightly set parameters and time frames in comparably structured and controlled environments.

Autonomous weapons are distinguish-able from their precursors. They would be able to operate without human control or supervision in dynamic, unstructured, open environments, attacking a variety of targets. They would operate over an extended period of time after activation and would potentially be able to learn and adapt to their situations. To be fair, this juxtaposition is artificial and glosses over an important gray area by leaving aside the fact that autonomous functionality is a continuum. After all, automatic systems, targeting humans at borders or automatically firing back at the source of incoming munitions, already raise questions relevant to the autonomy debate.

There arguably is a tacit understanding in the expert community and among diplomats in Geneva that the debate’s main focus is on future, mobile weapons platforms equipped with onboard sensors, computers, and decision-making algorithms with the capability to seek, identify, track, and attack targets autonomously. The autonomy debate thus touches on but is not primarily concerned with existing automatic defensive systems. In fact, depending on how the CCW ends up defining autonomous weapons systems, it might be well within reason to exempt those from regulation or a possible preventive ban if their sole purpose is to protect human life by exclusively targeting incoming munitions.

Drivers of Autonomy

It is underwater and in the air—less cluttered environments—where autonomy in weapons systems is currently advancing most rapidly. The X-47B in the United States, the United Kingdom’s Taranis, and the French nEUROn project are examples of autonomy testing in unmanned aerial vehicles.4 This trend is driven by the prospect of various benefits.

• Weapons autonomy removes the need for a control-and-communication link, which is vulnerable to disruption or capture and may reveal the system’s location and in which there is invariably some delay between the issuing of a command by the human operator and the execution of that command. Removing this latency generates a tactical advantage.

• It has been argued that because autonomous systems do not know fear, stress, or overreactions, they might render warfare more humane and prevent some of the atrocities of war. Machines are not only devoid of negative human emotions, but they also lack a self-preservation instinct, so they could well delay returning fire, some say. They are supposed to allow for greater restraint and also better discrimination between civilians and combatants, resulting in an application of force in strict or stricter accordance with international humanitarian law.5

Problems With Autonomy

In light of these anticipated benefits, one might expect militaries to unequivocally welcome the introduction of autonomous weapons systems. Yet, their reputation remains mixed at best. For instance, there are multiple operational risks. The potential for high-tempo fratricide, much greater than at human intervention speeds, incentivizes militaries to retain humans in the chain of decision-making as a fail-safe mechanism.6

Above and beyond such tactical concerns, these systems threaten to introduce a destabilizing factor at the strategic level. For one, autonomous weapons systems generate new possibilities for disarming surprise attacks. Small, stealthy, or extremely low-flying systems, or swarms, are difficult to detect and defend against. When nuclear weapons or strategic command-and-control systems are or are perceived to be put at greater risk, autonomous conventional capabilities end up causing instability at the strategic level. Further, trading algorithms at the stock market already provide cautionary tales of unforeseeable and costly algorithm interactions. Introducing autonomous systems into conflict runs the risk of generating similarly unexpected outcomes. The sequence of events developing at rapid speed from the interaction of autonomous systems or swarms of two adversaries could never be trained, tested, nor truly foreseen. An uncontrolled escalation from crisis to war is entirely within the realm of possibilities.7

Human decision-making in armed conflict requires complex assessments to ensure a discriminate and proportionate application of military force in accordance with international humanitarian law. Not only are combatants and noncombatants often not clearly distinguishable, but weighing a potential risk to civilians or damage to civilian objects against the anticipated military advantage in the fog of war poses a challenge to even the most experienced of commanders. In the foreseeable future, it is doubtful that these processes can be replicated in software code; but if these systems cannot be designed to abide by international humanitarian law, the previously mentioned hope for them rendering war more humane is misguided.8

A closely related aspect is that it remains unclear who would be legally accountable if civilians were unlawfully injured or killed by autonomous weapons systems, especially because targeting processes in modern militaries are such an immensely complex, strategic, multilevel endeavor. An artificially intelligent system tasked with autonomous targeting would thus not only need to replace various human specialists, creating what has become known as the “accountability gap” because a machine cannot be court-martialed, it would essentially require a human abdication of political decision-making.9

Leaving military, legal, and political considerations aside moves a more fundamental problem into focus. From an ethical point of view, it is argued that autonomous weapons systems violate fundamental human values.10 Delegating the decision to kill a human to an algorithm in a machine, which is not responsible for its actions in any meaningful ethical sense, can arguably be understood to be an infringement on basic human dignity, representing what in moral philosophy is known as a malum in se, a wrong in itself. This peculiar consideration is reflected in the public’s deep concerns in the United States and internationally regarding autonomy in weapons systems.11

In sum, there are many reasons—military, legal, political, ethical—for engaging in preventive arms control measures regarding autonomous weapons systems.

The Need to Maintain Human Control Over Weapons“Whether for legal, ethical or military-operational reasons, there is broad agreement on the need for human control over weapons and the use of force. However, it remains unclear whether human control at the stages of the development and the deployment of an autonomous weapon system is sufficient to overcome minimal or no human control at the stage of the weapon system’s operation—that is, when it independently selects and attacks targets. There is now a need to determine the kind and degree of human control over the operation of weapon systems that are deemed necessary to comply with legal obligations and to satisfy ethical and societal considerations.” —Statement of the International Committee of the Red Cross, |

CCW Process

The purpose of the CCW, to which 123 states are currently party, is to prohibit or restrict the use of certain conventional weapons that are considered excessively injurious or whose effects are indiscriminate. The CCW is a framework convention with a set of protocols that regulate specific types of weapons; Protocol IV, for instance, preventively banned blinding laser weapons.

Deliberations at the CCW are known to be notoriously slow and prone to failure. Protocol II on land mines, for example, failed to adequately address humanitarian concerns raised by anti-personnel mines, leading Canada and other governments to cooperate with nongovernmental organizations to work for a ban outside the CCW, culminating in the adoption of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, or Ottawa Treaty. CCW deliberations on cluster munitions failed in 2011 to produce an outcome, leaving the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, created outside CCW and UN auspices, as the sole international instrument to specifically regulate these weapons.

Yet, so far autonomous weapons systems have been the subject of exceptionally dynamic talks and climbed the CCW agenda with unprecedented speed. The upcoming CCW fifth review conference in December 2016 provides states with an incentive to inject even more ambition into the process. Since 2013, 14 countries have called for a preventive ban on autonomous weapons systems, which could be concluded via a new CCW protocol. Notably, no country has vigorously defended or even argued for the development and deployment of autonomous weapons systems. Only two nations—Israel and the United States—have argued that such systems may offer certain benefits.

On the one hand, it seems plausible that CCW states-parties have discovered their genuine interest in a development deemed to require urgent regulation and are keen to demonstrate the CCW’s capacity to act. On the other hand, the CCW has a fearsome reputation as a place where good ideas go to die a slow death.

The civil society movement pushing for a legally binding prohibition on autonomous weapons systems within the CCW framework is organized and spearheaded by the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, a coalition of more than 61 groups in 26 countries coordinated by Human Rights Watch. Its members include Amnesty International, the UK group Article 36, and the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, a small network of experts and professionals with recognized academic and practical knowledge of AI, robotics research, and arms control. The campaign goal is to prohibit the development, production, and use of autonomous weapons systems in order to retain meaningful human control over life-and-death decisions in battle, policing, and other circumstances.

The military relevance of this envisioned technical capability, however, is greater than that of blinding lasers, and thus this comparison case of a successful prohibition carries only so far. The dual-use issue is more complex as well. Research on autonomous robots is underway in countless university laboratories and large and small companies due to the massive commercial interest in the field. The integration of commercial off-the-shelf technology has become a driver of developments in the field of military technology, and AI and robotics have officially been declared cornerstones of the U.S. military’s “third offset” strategy12 to counter rising powers. Therefore, can a preventive ban be achieved within the CCW framework?

The military relevance of this envisioned technical capability, however, is greater than that of blinding lasers, and thus this comparison case of a successful prohibition carries only so far. The dual-use issue is more complex as well. Research on autonomous robots is underway in countless university laboratories and large and small companies due to the massive commercial interest in the field. The integration of commercial off-the-shelf technology has become a driver of developments in the field of military technology, and AI and robotics have officially been declared cornerstones of the U.S. military’s “third offset” strategy12 to counter rising powers. Therefore, can a preventive ban be achieved within the CCW framework?

Perspectives for Arms Control

The human brain needs time for complex evaluation and decision-making processes, time that it cannot be denied in the interaction between human and machine if the human role is to remain relevant, in other words, if the decision-making process is merely to be supported, not dominated, by the machine. Establishing where to draw that line is shaping up to be the key challenge in Geneva. Arriving at a decision in that regard would also mean producing the first definition of autonomous weapons systems in terms of international law.

At the CCW meetings, the almost mantra-like repetition of a shared commitment to retain “meaningful human control” over the use of force by states-parties and civil society actors has become pivotal. Keeping weapons systems under meaningful human control and banning autonomous weapons systems are two sides of the same coin.

The concept of meaningful human control introduced at the end of 2013 by Article 36, a member of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, has since been taken up by governments. It goes beyond the “appropriate levels of human judgment” approach specified by the 2012 Pentagon directive. After all, the absence of human judgment might end up being deemed appropriate in some circumstances. Thus, the argument that human control over life-and-death decisions must always be in place in a significant or meaningful fashion, as more than just a mindless pushing of a button by a human in response to a machine-processed stream of information.

According to current practice, a human weapons operator must have sufficient information about the target and sufficient control over the weapon and must be able to assess its effects in order to be able to make decisions in accordance with international law. At the same time, modern weapons systems are already highly computerized and automated, a trend that is only accelerating. So, determining how much human judgment can be replaced by algorithms before human control is no longer “meaningful” involves various technical, legal, ethical, and political considerations.

In light of this, four possible outcomes can be predicted for the CCW process. The first would be a legally binding and preventive multilateral arms control agreement derived by consensus in the CCW and thus involving the major stakeholders, the outcome referenced as “a ban.” Considering the growing number of states-parties calling for a ban and the large number of governments calling for meaningful human control and expressing considerable unease with the idea of autonomous weapons systems, combined with the fact that no government is openly promoting their development, this seems possible. It would require mustering considerable political will. Verification and compliance for a ban, as well as for weaker restrictions, would then require creative arms control solutions. After all, with full autonomy in a weapons system eventually coming down to merely flipping a software switch, how can one tell if a specific system at a specific time is not operating autonomously? A few arms control experts are already wrapping their heads around these questions.13

The second outcome would be restrictions short of a ban. The details of such an agreement are impossible to predict, but it is conceivable that governments could agree, for example, to limit the use of autonomous weapons systems, such as permitting their use against materiel only.

The third would be a declaratory, nonbinding agreement on best practices. Such a code of conduct would likely emphasize compliance with existing international humanitarian law and rigorous weapons review processes, in accordance with Article 36 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.

Finally, there may be no tangible result, perhaps with one of the technologically leading countries setting a precedent by fielding autonomous weapons systems. That would certainly prompt others to follow, fueling an arms race. In light of some of the most advanced standoff weapons, such as the U.S. Long Range Anti-Ship Missile or the UK Brimstone, each capable of autonomous targeting during terminal flight phase, one might argue that the world is already headed for such an autonomy arms race.

Implementing autonomy, which mainly comes down to software, in systems drawn from a vibrant global ecosystem of unmanned vehicles in various shapes and sizes is a technical challenge, but doable for state and nonstate actors, particularly because so much of the hardware and software is dual use. In short, autonomous weapons systems are extremely prone to proliferation. An unchecked autonomous weapons arms race and the diffusion of autonomous killing capabilities to extremist groups would clearly be detrimental to international peace, stability, and security.

This underlines the importance of the current opportunity for putting a comprehensive, verifiable ban in place. The hurdles are high, but at this point, a ban is clearly the most prudent and thus desirable outcome. After all, as long as no one possesses them, a verifiable ban is the optimal solution. It stops the currently commencing arms race in its tracks, and everyone reaps the benefits. A prime goal of arms control would be fulfilled by facilitating the diversion of resources from military applications toward research and development for peaceful purposes—in the fields of AI and robotics no less, two key future technologies.

This situation presents a fascinating and instructive case for arms control in the 21st century. The outcome of the current arms control effort regarding autonomous weapons systems can still range from an optimal preventive solution to a full-blown arms race. Although this process holds important lessons, for instance regarding the valuable input that epistemic communities and civil society can provide, it also raises vexing questions, particularly if and how arms control will find better ways for tackling issues from a qualitative rather than quantitative angle.

The autonomous weapons systems example points to a future in which dual-use reigns supreme and numbers are of less importance than capabilities, with the weapons systems to be regulated, potentially disposable, 3D-printed units with their intelligence distributed in swarms. Consequently, more thinking is needed about how arms control can target specific practices rather than technologies or quantifiable military hardware.

‘We Will Not Delegate Lethal Authority...’“We will not delegate lethal authority for a machine to make a decision. The only time we’ll delegate [such] authority [to a machine] is in things that go faster than human reaction time, like cyber or electronic warfare…. We might be going up against a competitor who is more willing to delegate authority to machines than we are and, as that competition unfolds, we’ll have to make decisions on how we can best compete. It’s not something that we have fully figured out, but we spend a lot of time thinking about it.” —U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work, |

Lastly, some policy recommendations are in order. The United States “will not delegate lethal authority for a machine to make a decision,” U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work said in March. Yet, he added that such self-restraint may be unsustainable if an authoritarian rival acts differently. “It’s not something that we have fully figured out, but we spend a lot of time thinking about it,” Work said.14 The delegation of lethal authority to weapons systems will not inexorably happen if CCW states-parties muster the political will not to let it happen. States can use the upcoming CCW review conference in December to go above and beyond the recommendation from the 2016 meeting on lethal autonomous weapons systems and agree to establish an open-ended group of governmental experts with a strong mandate to prepare the basis for new international law, preferably via a ban.

Further, a prohibition on autonomous weapons systems should be pursued at the domestic level. Most countries actively engaged in research and development on such systems have not yet formulated policies or military doctrines. Member states of the European Union especially should be called to action.

Even if the CCW process were to fizzle out, like-minded states could cooperate and, in conjunction with the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, continue pursuing a ban through other means. The currently nascent social taboo against machines autonomously making kill decisions meets all the requirements for spawning a “humanitarian security regime.”15

Autonomous weapons systems would not be the first instance when an issue takes an indirect path through comparably softer social international norms and stigmatization to a codified arms control agreement. In other words, even if technology were to overtake the current process, arms control remains as possible as it is sensible.

ENDNOTES

1. Future of Life Institute, “Autonomous Weapons: An Open Letter from AI and Robotics Researchers,” July 28, 2015, http://futureoflife.org/open-letter-autonomous-weapons/.

2. Frank Sauer, “Autonomous Weapons Systems: Humanising or Dehumanising Warfare?” Global Governance Spotlight, No. 4 (2014), http://icrac.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/GGS_04-2014_Sauer_2014-06-13_en.pdf.

3. U.S. Department of Defense, “Autonomy in Weapon Systems,” Directive No. 3000.09, November 21, 2012.

4. Frank Sauer and Niklas Schörnig, “Killer Drones: The Silver Bullet of Democratic Warfare?” Security Dialogue, Vol. 43, No. 4 (August 2012): 363-380.

5. Ronald C. Arkin, “The Case for Ethical Autonomy in Unmanned Systems,” Journal of Military Ethics, Vol. 9, No. 4 (2010): 332-341.

6. Paul D. Scharre, “Autonomous Weapons and Operational Risk,” Center for a New American Security, February 2016, http://www.cnas.org/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/CNAS_Autonomous-weapons-operational-risk.pdf.

7. Jürgen Altmann and Frank Sauer, “Speed Kills! Why We Need to Hit the Brakes on ‘Killer Robots,’” International Committee for Robot Arms Control (ICRAC), 2016, http://icrac.net/2016/04/speed-kills-why-we-need-to-hit-the-brakes-on-killer-robots.

8. Noel E. Sharkey, “The Evitability of Auto-nomous Robot Warfare,” International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 94, No. 886 (Summer 2012): 787-799, https://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/review/2012/irrc-886-sharkey.pdf.

9. Heather M. Roff, “The Strategic Robot Problem: Lethal Autonomous Weapons in War,” Journal of Military Ethics, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2014): 211-227.

10. Peter Asaro, “On Banning Autonomous Weapon Systems: Human Rights, Automation, and the Dehumanization of Lethal Decision-Making,” International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 94, No. 886 (Summer 2012): 687-709.

11. Charli Carpenter, “Beware the Killer Robots: Inside the Debate Over Autonomous Weapons,” Foreign Affairs, July 3, 2013, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139554/charli-carpenter/beware-the-killer-robots#cid=soc-twitter-at-snapshot-beware_the_killer_robots-000000; Open RoboEthics Initiative, “The Ethics and Governance of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems: An International Public Opinion Poll,” November 9, 2015, http://www.openroboethics.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ORi_LAWS2015.pdf.

12. The so-called first offset was the use of nuclear deterrence against the large conventional forces of the Soviet Union starting in the 1950s, and the second offset in the 1970s and 1980s was the fielding of precision munitions and stealth technologies to counter the air and ground forces of adversaries. The third offset looks to innovation and emerging technologies, such as AI, to retain an advantage against adversaries. See Robert Work, “The Third U.S. Offset Strategy and Its Implications for Partners and Allies” (speech, Washington, DC, January 28, 2015), http://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/606641/the-third-us-offset-strategy-and-its-implications-for-partners-and-allies.

13. Mark Gubrud and Jürgen Altmann, “Compliance Measures for an Autonomous Weapons Convention,” ICRAC Working Paper, No. 2 (May 2013), http://icrac.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Gubrud-Altmann_Compliance-Measures-AWC_ICRAC-WP2-2.pdf.

14. See “David Ignatius and Pentagon’s Robert Work Talk About New Technologies to Deter War,” The Washington Post, video, March 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/postlive/david-ignatius-and-pentagons-robert-work-on-efforts-to-defeat-isis-latest-tools-in-defense/2016/03/30/0fd7679e-f68f-11e5-958d-d038dac6e718_video.html.

15. Denise Garcia, “Humanitarian Security Regimes,” International Affairs, Vol. 91 No. 1 (January 2015): 55-75.

Frank Sauer is a senior research fellow and lecturer at Bundeswehr University in Munich. He is the author of Atomic Anxiety: Deterrence, Taboo and the Non-Use of U.S. Nuclear Weapons (2015) and a member of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control.

When nuclear testing ended in 1992, the United States had recently completed production of many new nuclear weapons during the Reagan modernization of the 1980s. The warheads that remain in the current stockpile were young, with an average age of six years. Today, however, the United States has the oldest stockpile it has ever had and the smallest stockpile since the Eisenhower administration, reduced by more than 85 percent from the Cold War peak. The intent of the LEPs is not to introduce new weapons; the programs are focused on extending the life of current U.S. nuclear weapons while improving safety and security and maintaining reliability.

When nuclear testing ended in 1992, the United States had recently completed production of many new nuclear weapons during the Reagan modernization of the 1980s. The warheads that remain in the current stockpile were young, with an average age of six years. Today, however, the United States has the oldest stockpile it has ever had and the smallest stockpile since the Eisenhower administration, reduced by more than 85 percent from the Cold War peak. The intent of the LEPs is not to introduce new weapons; the programs are focused on extending the life of current U.S. nuclear weapons while improving safety and security and maintaining reliability.

France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States and, perhaps, Russia and China saw the Iran case primarily as a compliance problem. Iran broke the rules of the nonproliferation regime, specifically International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards and disclosure requirements. The IAEA and subsequently the UN Security Council issued binding requirements of transparency and confidence building, including a demand that Iran “suspend all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities.”

France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States and, perhaps, Russia and China saw the Iran case primarily as a compliance problem. Iran broke the rules of the nonproliferation regime, specifically International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards and disclosure requirements. The IAEA and subsequently the UN Security Council issued binding requirements of transparency and confidence building, including a demand that Iran “suspend all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities.” The tension between compliance and fairness will play out in general debates, as in NPT review conferences, and in future cases if and when a non-nuclear-weapon state seeks to develop indigenous capabilities to enrich uranium or separate plutonium. States and nongovernmental organizations will intensely debate whether the nuclear-weapon states are complying with their disarmament obligations and what are fair measures of progress toward that end. Discord also will be expressed over whether and how strengthened approaches to IAEA safeguards, including the toughened provisions of the additional protocol, are necessary to uphold the objectives of the NPT and whether inducements, or bargains, should be offered to make this more acceptable.

The tension between compliance and fairness will play out in general debates, as in NPT review conferences, and in future cases if and when a non-nuclear-weapon state seeks to develop indigenous capabilities to enrich uranium or separate plutonium. States and nongovernmental organizations will intensely debate whether the nuclear-weapon states are complying with their disarmament obligations and what are fair measures of progress toward that end. Discord also will be expressed over whether and how strengthened approaches to IAEA safeguards, including the toughened provisions of the additional protocol, are necessary to uphold the objectives of the NPT and whether inducements, or bargains, should be offered to make this more acceptable.  In his article (“

In his article (“ The CTBT has not entered into force because eight key states—China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United States, also known as the Annex 2 states—have failed to ratify it. The resolution, adopted Sept. 23, urges those countries to ratify “without further delay” and calls on all states to refrain from conducting nuclear tests, emphasizing that current testing moratoria contribute to “international peace and stability.”

The CTBT has not entered into force because eight key states—China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United States, also known as the Annex 2 states—have failed to ratify it. The resolution, adopted Sept. 23, urges those countries to ratify “without further delay” and calls on all states to refrain from conducting nuclear tests, emphasizing that current testing moratoria contribute to “international peace and stability.”

In a Sept. 21 speech at the United Nations, Austrian Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz announced that his country, together with a group of other states, would press for such talks since “experience shows that the first step to eliminate weapons of mass destruction is to prohibit them through legally binding norms.”

In a Sept. 21 speech at the United Nations, Austrian Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz announced that his country, together with a group of other states, would press for such talks since “experience shows that the first step to eliminate weapons of mass destruction is to prohibit them through legally binding norms.” That political environment includes a decision, first reported by Foreign Policy on May 27, that the Obama administration had suspended cluster munition transfers to Saudi Arabia following evidence of civilian casualties from their use in attacks in Yemen. A U.S. House of Representatives action to make that suspension more durable nearly passed in a June vote of 204-216 on an amendment to the fiscal year 2017 defense appropriations bill that would have barred the use of U.S. funds to authorize the transfer of cluster munitions to Saudi Arabia.

That political environment includes a decision, first reported by Foreign Policy on May 27, that the Obama administration had suspended cluster munition transfers to Saudi Arabia following evidence of civilian casualties from their use in attacks in Yemen. A U.S. House of Representatives action to make that suspension more durable nearly passed in a June vote of 204-216 on an amendment to the fiscal year 2017 defense appropriations bill that would have barred the use of U.S. funds to authorize the transfer of cluster munitions to Saudi Arabia.

The report notes compliance with constraints set by the accord, among them Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium being less than the 300-kilogram cap, its enrichment levels remaining at 3.67 percent uranium-235, and Tehran using only 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges for enrichment at its Natanz facility.

The report notes compliance with constraints set by the accord, among them Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium being less than the 300-kilogram cap, its enrichment levels remaining at 3.67 percent uranium-235, and Tehran using only 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges for enrichment at its Natanz facility.  Libya requested in February that the OPCW, the body charged with overseeing implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), provide in-country assistance in destroying the precursors. Then in July, Libya requested that the precursors quickly be moved outside of the country for elimination due to concerns that they could fall into the hands of nonstate actors amid fighting by rival militias.

Libya requested in February that the OPCW, the body charged with overseeing implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), provide in-country assistance in destroying the precursors. Then in July, Libya requested that the precursors quickly be moved outside of the country for elimination due to concerns that they could fall into the hands of nonstate actors amid fighting by rival militias. The destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons outside of Syria set a precedent for transporting the precursors out of Libya for destruction. The CWC normally requires a state to destroy stocks within their territory.

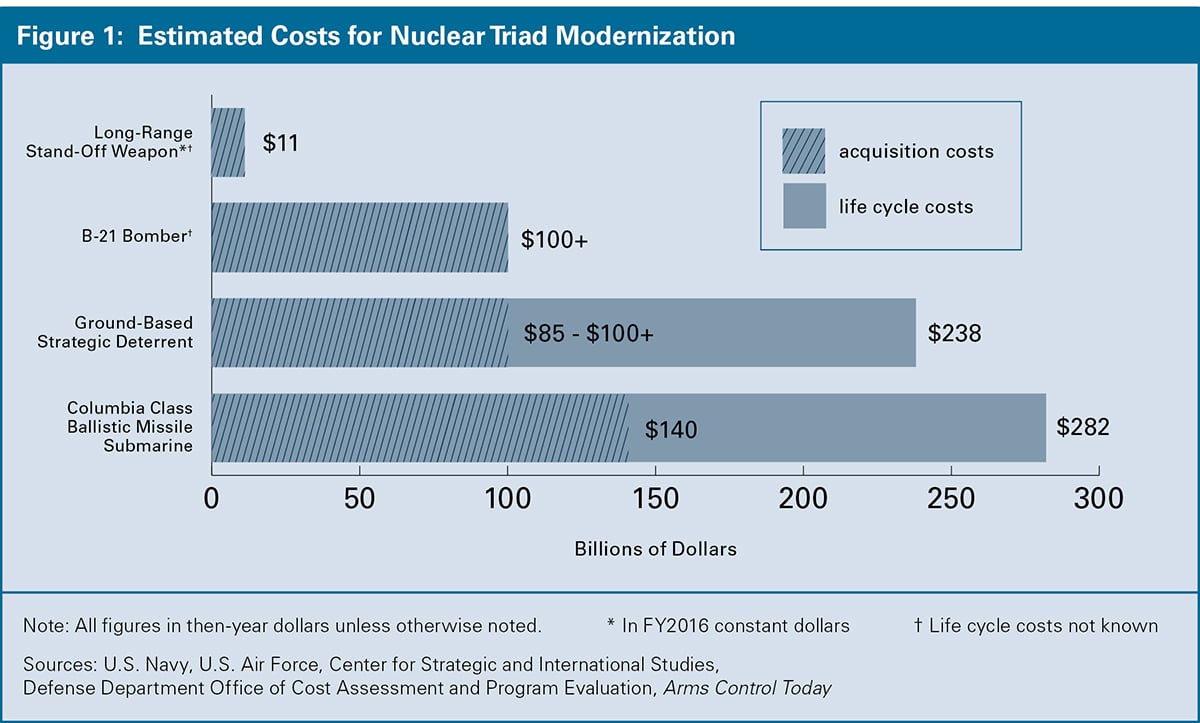

The destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons outside of Syria set a precedent for transporting the precursors out of Libya for destruction. The CWC normally requires a state to destroy stocks within their territory.  The growing price of the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program, as it is known, comes as the Obama administration continues to grapple with how to pay for current plans to modernize U.S. nuclear forces and has raised questions about whether there are cheaper alternatives to sustain the ICBM leg of the nuclear triad.

The growing price of the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program, as it is known, comes as the Obama administration continues to grapple with how to pay for current plans to modernize U.S. nuclear forces and has raised questions about whether there are cheaper alternatives to sustain the ICBM leg of the nuclear triad.