April 2024

By David Goldfischer

Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer has educated a vast audience about a critical moment in world history. It also takes its viewers to a dark place, in which J. Robert Oppenheimer is punished for his effort to avert a nuclear arms race when he is stripped of his security clearance. As the movie expresses his thoughts, he had started then failed to stop “a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world.”

That might leave some viewers wondering how Oppenheimer hoped to prevent what he accurately foresaw as an unwinnable superpower nuclear arms race. Despite the personal struggles portrayed in the movie, he worked ceaselessly toward identifying a practical path toward that goal. Unfortunately, the answer he ultimately found has been all but forgotten.

That might leave some viewers wondering how Oppenheimer hoped to prevent what he accurately foresaw as an unwinnable superpower nuclear arms race. Despite the personal struggles portrayed in the movie, he worked ceaselessly toward identifying a practical path toward that goal. Unfortunately, the answer he ultimately found has been all but forgotten.

His initial hope was for comprehensive international control of everything from uranium mining to deployed weapons. As reflected in his work on the 1946 Acheson-Lilienthal report, that approach was overtaken by the deepening Cold War and the 1949 Soviet atomic bomb test.1

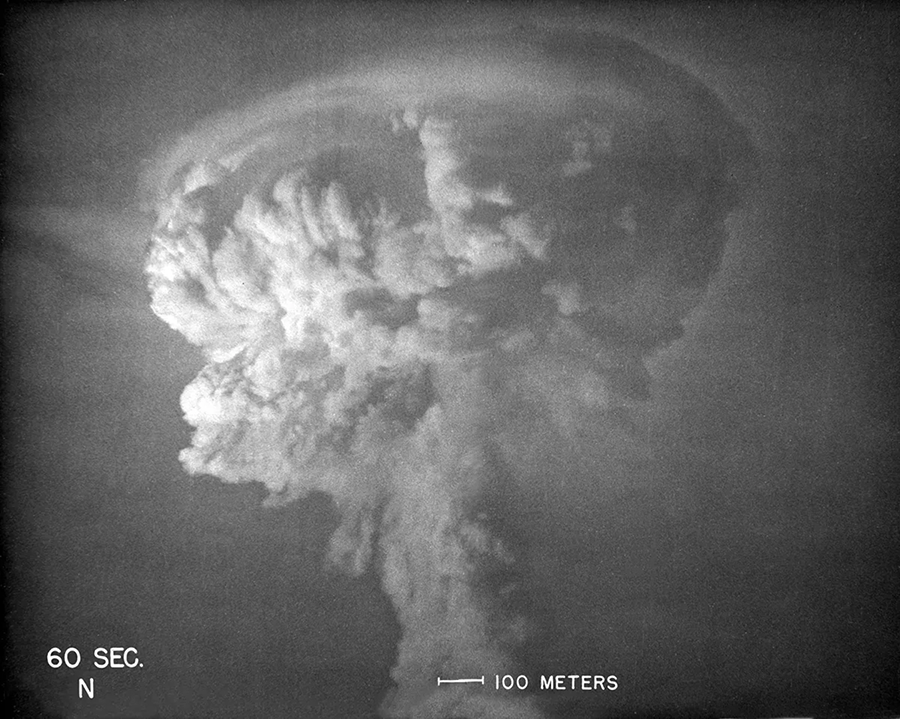

In that new context, Oppenheimer turned to a search for a nuclear policy that could contain the Soviet threat while avoiding capabilities for “exterminating civilian populations.” That phrase is from a majority report in 1949, which he authored, of the General Advisory Committee of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.2 In it, he distinguished between atomic weapons sufficient for deterring attack and the development of a hydrogen bomb, whose almost limitless explosive power and “the global effects of its radioactivity,” would vastly magnify the nuclear danger. The committee’s call to suspend hydrogen bomb development while supporting work on low-yield tactical nuclear weapons reflected Oppenheimer’s emerging vision of minimally sufficient nuclear deterrence. Consistent with that approach and further antagonizing supporters of a nuclear airpower buildup, Oppenheimer participated in the military’s 1951 Project Vista, which argued that Europe could be defended with short-range tactical nuclear weapons rather than long-range strategic bombers.3

He next moved to consider whether efforts at population defense could contribute to the combined goals of deterring attack while avoiding civilian “extermination.” From the perspective of the U.S. Air Force leadership, his answer provided final proof of Oppenheimer’s treacherous “pattern of activities.”4 For those who shared his view that a nuclear arms race risked world destruction, however, his emerging policy approach represented a radical advance in how to reduce the nuclear danger. The “father of the atom bomb” was about to create the first coherent vision of superpower nuclear arms control.

A New Proposal

Oppenheimer’s new proposal, to put it simply, was for a superpower agreement that would avoid a buildup of bombs and bombers and instead direct Soviet and U.S. efforts toward defending their populations against nuclear attack. One might describe this approach as “mutual defense emphasis.”

It is understandable that his call for this arms control concept was left out of the film as peripheral to the high drama of its protagonist’s life and times. Yet, it also was ignored in the biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, on which the movie largely was based, and has received scant attention in most other histories of the nuclear age.

Because all scholars now agree that Oppenheimer’s banishment as an adviser on nuclear policy was unjust, it is worth examining whether the arms control concept that contributed to his downfall warrants reconsideration. That requires a look back at 1952, when Oppenheimer followed his work on Project Vista by joining a 1952 summer study at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, which assessed prospects for defending the U.S. homeland against nuclear-armed bombers.5

The study concluded that a full-scale continental defense could intercept 60 to 80 percent of enemy bombers and that technological advances promised far greater effectiveness. Based on those findings, Oppenheimer concluded that although defense against a Soviet “knockout blow” technically was achievable, it would require that the Soviets decide to limit their own buildup of nuclear-capable long-range bombers. Although formal agreements were unlikely in that Cold War climate, Oppenheimer envisioned a tacit understanding in which the superpowers would couple low levels of bombers with large-scale efforts at detection and interception. In that case, he concluded, deterrence could be based on mutual fears that few if any bombers would reach their targets.

At the time, the Soviet Union was focused on constructing a multitiered radar network and thousands of jet interceptors, while deploying no nuclear-capable intercontinental-range bombers, essentially the reverse of the initial U.S. reliance on a purely offensive strategy. Oppenheimer expressed the hope that, in return for being spared a buildup of U.S. nuclear airpower that was certain to overwhelm even the massive Russian defensive effort, Moscow might be prepared to make deep cuts in its conventional forces threatening Western Europe. Only such bilateral concessions could avert the threats that each side feared most.

Oppenheimer then took this logic a step further. Should the day arrive when improved superpower relations revived interest in nuclear disarmament, he proposed that nationwide defenses would be a vital supplement to a verification regime. Although verification alone could not eliminate fears of hidden nuclear weapons and bombers, extensive defensive deployments could resolve that formidable obstacle to comprehensive offensive disarmament. As he explained in a 1953 article, a combination of robust verification measures and large-scale defenses could make “steps of evasion far too vast to conceal or far too small to have, in view of existing measures of defense, a decisive strategic effect.”6

Oppenheimer then took this logic a step further. Should the day arrive when improved superpower relations revived interest in nuclear disarmament, he proposed that nationwide defenses would be a vital supplement to a verification regime. Although verification alone could not eliminate fears of hidden nuclear weapons and bombers, extensive defensive deployments could resolve that formidable obstacle to comprehensive offensive disarmament. As he explained in a 1953 article, a combination of robust verification measures and large-scale defenses could make “steps of evasion far too vast to conceal or far too small to have, in view of existing measures of defense, a decisive strategic effect.”6

That article became famous for its appeal to the American people for candor regarding the impending Soviet capability to destroy the nation’s “heart and life” even if the United States attacked first. In a nonpublic forum, Oppenheimer expressed hope that such candor would galvanize public support for a major effort to build a continental defense and negotiate a bilateral limit on offenses. Informed U.S. citizens, as a later advocate of this approach put it, would “prefer live Americans to dead Russians.”7

These ideas had been developed in meetings of the Oppenheimer-led Panel of Consultants on Disarmament during the waning months of the Truman administration. Its work included a stillborn “no first test” proposal for the hydrogen bomb, based on the argument that stopping at the brink of testing would prevent both sides from developing deliverable weapons while enabling a rapid response if one side broke the agreement.8 The first U.S. nuclear test occurred while the panel was still deliberating.

The panel’s report was delivered to newly elected President Dwight Eisenhower, who then heard direct appeals from panel members Oppenheimer, CIA Director Allen Dulles, and leading U.S. science adviser Vannevar Bush.9 Discussions within the administration embraced their call for a continental defense system while rejecting their accurate prediction that homeland defense would prove futile without an agreement to limit offensive forces. A year later, Dulles’ older brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, would announce the U.S. doctrine of “massive retaliation,” justifying the unfolding buildup to around 3,000 nuclear-armed bombers by the end of the 1950s.

A Bitter Attack

Oppenheimer’s case for mutual defense emphasis came under bitter attack by Air Force leadership, which regarded support for U.S. nuclear superiority as a litmus test of patriotism. A sample of the prevalent conspiratorial thinking was the testimony of the chief Air Force scientist, David Griggs, during the hearings that led to the revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance. “It was…told me by people who were approached to join the summer study that in order to achieve world peace…it was necessary not only to strengthen the air defense of the continental United States, but also to give up something, and the thing that was recommended that we give up was the…strategic part of our total air power,” Griggs said.10

It is largely forgotten that the original vision of nuclear arms control was based on restricting the offense to make strategic defense possible. In 1957 the arrival of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), demonstrated by the Soviet launch of Sputnik, would make that arms control approach appear foredoomed, and U.S. arms control supporters soon seized on a moment when shooting down ballistic missiles was literally impossible. In a radical shift from Oppenheimer’s arms control vision, these arms control supporters reasoned that the best outcome would be a superpower agreement to deploy ICBMs in large but equal numbers and protect them from nuclear attack by placing them underground in hardened concrete silos. Because neither side could hope to eliminate the other’s nuclear-armed missiles by striking first, the prospect of devastating retaliation against the aggressor’s population would freeze both sides in a state of stable mutual deterrence. The goal of arms control had shifted from the pursuit of offensive nuclear disarmament to the preservation of peace through an enduring “balance of terror.”

By the time the two sides developed plausibly effective defenses against missiles during the 1960s, this logic called for banning their deployment, and the United States proposed such a plan for “offense only” mutual deterrence to the Soviet Union in 1967. When Soviet leaders objected, arguing that it would be better to ban offenses and allow population defenses, the United States responded that it would simply overwhelm any Soviet anti-ballistic missile defensive system by expanding its ICBM force.

In 1972 the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty enshrined the principle of assured vulnerability to a nuclear holocaust, which has guided U.S.-Russian strategic arms control from then through the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). This approach soon became known as mutual assured destruction, a label created by Donald G. Brennan, who was also a supporter of mutual defense emphasis. He believed that the acronym MAD captured the insanity of entrusting safety to an arrangement based on forever avoiding accidental launches, miscalculation during a crisis, or a leader’s descent into insanity.

Oppenheimer’s defensive alternative to MAD had a remarkable if brief resurrection three decades later. President Ronald Reagan, facing widespread opposition to his 1983 call for a massive U.S. population defense known as the Strategic Defense Initiative, recast it from a nuclear victory strategy to a disarmament concept. Paul Nitze, Reagan’s senior arms control adviser, attended meetings of Oppenheimer’s 1952 disarmament panel as head of the Department of State’s policy planning staff. Now, as the Cold War waned, he embraced its call for a defense-protected disarmament regime, and Reagan approved his updated version of Oppenheimer’s arms control concept.

Presented to the Soviet arms control delegation in Geneva in January 1985, Nitze’s proposal called for a 10-year negotiated transition combining non-nuclear population defenses with complete offensive disarmament. His explanation of the need for nationwide defenses as a hedge against cheating verged on a verbatim repetition of Oppenheimer’s logic years earlier.

Nitze’s proposal initially was rejected by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, who scoffed at Reagan’s vague promise to share U.S. missile defense technology. Yet, the Cold War had reached a turning point, and Gorbachev soon called for “a change in the entire pattern of armed forces” toward “imparting an exclusively defensive character to them.” In October 1991, weeks before his fall from power, Gorbachev announced that the Soviets were ready “to consider proposals…on non-nuclear anti-ballistic missile defenses.” The chain from Oppenheimer to Nitze to Gorbachev would extend to the first two leaders of the Russian successor state.

Back to the Past

On February 1, 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin called for a global missile defense system that would enable countries to slash or eliminate their nuclear arsenals.11 If that proposal reflected the giddy idealism of a new era, including reliance on a non-existent space-based missile shield, the United States by then had lost any interest in exploring cooperative defenses with the weak Soviet successor state. Eight years later, in May 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush would stun new Russian President Vladimir Putin by withdrawing from the ABM Treaty, signaling a prospective U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup that a still floundering Russia would be unable to match.

Looking back at that moment in 2019, Putin’s views on that U.S. decision are worth quoting:

[I]f the US side…wanted to withdraw from the [t]reaty…I suggested working jointly on missile-defence projects that should have involved the United States, Russia and Europe. … Those were absolutely specific proposals. I am convinced that the world would be a different place today, had our US partners accepted this proposal. Unfortunately, this did not happen. We can see that the situation is developing in another direction; new weapons and cutting-edge military technology are coming to the fore. Well, this is not our choice.12

The world now finds itself confronted with the same basic problem that confronted Oppenheimer in the early 1950s, in which hopes for comprehensive arms control have yielded to major-power confrontation, including a race to incorporate destabilizing new weapons technologies. The United States, Russia, and China are pursuing improved offensive systems and defenses against aircraft and missiles of all types and ranges. Distinctions between offensive and defensive weapons and forces, crucial to all forms of arms control, are subordinated to whatever cost-effective blend of capabilities best advances war-fighting strategies. New START, already suspended in part over the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, will expire in 2026; and as China approaches nuclear parity with the original superpowers, MAD offers no formula for three-way assured-destruction force levels.

The world continues to live with Oppenheimer’s forecast that harnessing the destructive power of nuclear weapons will enable powerful nuclear states to overwhelm any adversary’s unilateral efforts to limit wartime damage. It also lives with his realistic fear that human survival cannot be entrusted permanently to what he called the “strange stability” of the resulting balance of terror.

Oppenheimer’s original arms control concept proved too idealistic for his time and place and may well be equally so today. From the perspective of all that has happened since, however, directing diplomacy toward achieving mutual defense emphasis may be less quixotic than current hopes to sustain the view that mutual assured vulnerability to annihilation is the best of all possible nuclear worlds. If the world manages to outlast the new cold war as it somehow survived the first, the door should not be closed to reconsidering, as Oppenheimer was the first to propose, that population defenses and offensive disarmament may be “necessary complements.”

ENDNOTES

1. Chester A. Barnard et al., “A Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy,” U.S. Department of State Publication 2498, March 16, 1946, https://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/atomic/item/1236.

2. Atomicarchive.com, “General Advisory Committee’s Majority and Minority Reports on Building the H-Bomb,” n.d., https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/hydrogen/gac-report.html (accessed March 27, 2024).

3. David C. Elliot, “Project Vista and Nuclear Weapons in Europe,” International Security, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1986): 163-183.

4. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: Transcript of Hearings Before Personal Security Board and Texts of Principal Documents and Letters (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970), p. 749.

5. Director’s Office, MIT Lincoln Laboratory, “The Soviet Atomic Threat, Oppenheimer, and the Need for National Air Defense,” The Bulletin, October 23, 2023, https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/153173/2023-10-20-Bulletin-The%20Soviet%20Atomic%20Threat%2c%20Oppenheimer%2c%20and%20the%20Need%20for%20National%20Air%20Defense.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

6. J. Robert Oppenheimer, “Atomic Weapons and American Policy,” Foreign Affairs, July 1953, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/robert-oppenheimer-atomic-weapons-american-policy.

7. Donald G. Brennan, “The Case for Population Defense,” in Why ABM? Policy Issues in the Missile Defense Controversy, ed. Johan Holst and William Schneider Jr. (New York: Pergamon Press, 1969), p. 108.

8. “Memorandum by the Panel of Consultants on Disarmament: The Timing of the Thermonuclear Test,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954, National Security Affairs, Vol. 2, Pt. 2, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54v02p2/d49 (undated).

9. “Report by the Panel of Consultants of the Department of State to the Secretary of State,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954, National Security Affairs, Vol. 2, Pt. 2, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54v02p2/d67.

10. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, p. 749.

11. Michael Parks, “Yeltsin Calls for Worldwide Antimissile Defense System,” Los Angeles Times, February 1, 1992.

12. President of Russia, “Interview With the Financial Times,” June 27, 2019, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60836.

David Goldfischer, an associate professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, is author of The Best Defense: Policy Alternatives for U.S. Nuclear Security From the 1950s to the 1990s (1993).

The agency has been pressing Iran for years to account for the presence of nuclear materials at two sites that were never declared to the IAEA as part of Iran’s nuclear program. The agency assesses that one of the locations, Turquazabad, was used to store nuclear materials and equipment, and the other, Varamin, included a pilot plant for uranium milling and conversion.

The agency has been pressing Iran for years to account for the presence of nuclear materials at two sites that were never declared to the IAEA as part of Iran’s nuclear program. The agency assesses that one of the locations, Turquazabad, was used to store nuclear materials and equipment, and the other, Varamin, included a pilot plant for uranium milling and conversion. After Putin made several veiled nuclear threats in the spring and fall of 2022, U.S. intelligence officials made public an assessment that senior Russian officials had discussed the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine that year. (See

After Putin made several veiled nuclear threats in the spring and fall of 2022, U.S. intelligence officials made public an assessment that senior Russian officials had discussed the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine that year. (See  Washington still views negotiations with Pyongyang as the only viable pathway to peace on the Korean peninsula and remains focused on denuclearizing North Korea, Jung Pak, the U.S. senior official for North Korea, said March 5 at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Washington still views negotiations with Pyongyang as the only viable pathway to peace on the Korean peninsula and remains focused on denuclearizing North Korea, Jung Pak, the U.S. senior official for North Korea, said March 5 at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The request for National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) weapons-related activities is 4 percent higher than appropriated by Congress for fiscal year 2024. In all, the budget request, unveiled on March 11, calls for $69 billion for nuclear weapons operations, sustainment, and modernization, including $49 billion for Pentagon programs and the rest for the NNSA. The combined budgets would be 22 percent higher than last year.

The request for National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) weapons-related activities is 4 percent higher than appropriated by Congress for fiscal year 2024. In all, the budget request, unveiled on March 11, calls for $69 billion for nuclear weapons operations, sustainment, and modernization, including $49 billion for Pentagon programs and the rest for the NNSA. The combined budgets would be 22 percent higher than last year.