December 2022

By Kelsey Davenport

Halfway into his first term, U.S. President Joe Biden faces the reality that one of his most significant foreign policy promises remains unmet: returning the United States and Iran to compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).1

Tragically, time nearly has run out to achieve this commitment. If Biden does not start exploring other options to stabilize the growing nuclear crisis, the United States could have to contend with an Iranian regime on the brink of possessing nuclear weapons or with a conflict to prevent it.

Tragically, time nearly has run out to achieve this commitment. If Biden does not start exploring other options to stabilize the growing nuclear crisis, the United States could have to contend with an Iranian regime on the brink of possessing nuclear weapons or with a conflict to prevent it.

Restoring the JCPOA even at this late date still would significantly reduce the proliferation risk posed by Iran’s rapidly advancing nuclear program and restore critical monitoring mechanisms. Nevertheless, the Iranian negotiating strategy casts doubt on President Ebrahim Raisi’s current interest in resurrecting the accord.

After closing in on an agreement to revive the JCPOA in August, Iran’s 11th-hour demand that any agreement end the investigation by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) into Iran’s nuclear past and prohibit such probes in the future stalled momentum toward a deal.2 The United States and its JCPOA partners (China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom) have no role in negotiating over the IAEA safeguards mandate, a fact of which Iran is well aware. Iran’s continued investment in new nuclear capabilities that cannot be fully reversed and have no civil nuclear justification raises further questions about whether Iran is serious about returning to the accord.

In addition to Iran’s intransigence in negotiations, political will to reach a deal is waning in the United States and Europe. Since talks to restore the JCPOA stalled, protests erupted throughout Iran after the country’s morality police beat a young woman, Mahsa Amini, to death for improperly wearing a headscarf. The Biden administration quickly expressed support for the protesters and is now under domestic political pressure to refrain from any actions that could be perceived as legitimizing or enriching the regime in Tehran. Iran’s sale of drones to Russia, in violation of UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the JCPOA, has inflamed tensions further, making negotiations even more difficult.

Robert Malley, U.S. special envoy for Iran, said on November 14 that the Biden administration is open to resuming diplomacy with Iran “when and if” the time comes, but he reiterated that the U.S. focus is on “what is happening in Iran…the sale of armed drones by Iran to Russia…and the liberation of our hostages.”3

Malley would not put a time frame on how long the administration will keep open the option of returning to the JCPOA, but he said Washington is continuing to apply pressure and sanctions while talks are stalled. If this is Biden’s plan B for addressing the nuclear crisis, it will not stabilize the situation, not least because Iran can ratchet up its nuclear program far more quickly than the United States can turn up the sanctions pressure.

Washington’s European partners appear more willing to acknowledge that prospects for restoring the JCPOA have diminished severely and that it is time to consider a new approach. French President Emmanuel Macron suggested on November 14 that a “new framework” will likely be necessary for addressing the nuclear crisis.4

It is critical that the Biden administration, as well as the Europeans, outline options for a new diplomatic initiative. With the nuclear program steadily advancing and with Tehran facing new political pressures that make a decision to produce a nuclear bomb increasingly likely, the United States cannot afford to let this major security challenge fester any longer.

A Dangerous Nuclear Acceleration

When Iran first began violating the JCPOA’s limits in May 2019, a year after U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the accord and reimposed sanctions, the breaches were calibrated carefully. Designed to be reversible quickly, they largely comprised instances where Iran resumed nuclear activities that had been limited under the JCPOA.5 This deliberate response suggests that Iran was trying to preserve space to restore the JCPOA by putting pressure on the United States to return to the accord while signaling that Iran had no intention of developing nuclear weapons or investing in new weapons-relevant research.

Iran’s strategy shifted, however, in December 2020 when the Iranian parliament passed a law that required the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran to further accelerate the country’s nuclear program and reduce IAEA access. The parliament pushed the law through after Israel assassinated Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the man often called the father of Iran’s pre-2003 nuclear weapons program, in November 2020.

When Raisi became president in August 2021, he continued aggressively expanding Iran’s nuclear program into more proliferation-sensitive areas beyond what was required by the December 2020 law, including the unprecedented step of enriching uranium to 60 percent U-235 in April 2021. The decision to begin enrichment to this level was made shortly after an explosion at the Natanz uranium-enrichment complex. That was another serious escalation that cannot be fully reversed given the knowledge Tehran gained from the enrichment process.

Due to these breaches, Iran’s nuclear program is more advanced than at any point in the country’s history. As of November 2022, Tehran could produce enough weapons-grade uranium for a bomb in fewer than seven days. By comparison, that period, often called the breakout period, was two to three months when the United States began negotiations on the JCPOA in 2013 and about 12 months when the JCPOA was fully implemented.6

The risk posed by the shrinking breakout window is further compounded by the December 2020 law’s requirement that Iran suspend aspects of its more intrusive safeguards arrangement with the IAEA, known as the additional protocol to Iran’s safeguards agreement, and the continuous surveillance of key nuclear sites required by the JCPOA. Halting implementation of these measures in February 2021 eliminated IAEA access to facilities, such as centrifuge production workshops, that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials. The suspension also reduced the tools available for the agency to verify that Iran’s nuclear program is peaceful. Iran continues to implement a less intrusive comprehensive safeguards agreement, as required by the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), but history has demonstrated that these agreements are insufficient in preventing proliferation.7

As a result of the reduced access, Iran could amass a significant quantity of bomb-grade material at some point between IAEA inspections, raising the risk that a move to produce weapons-grade material would not be detected. Although weaponization could still take two years, these processes would take place at covert facilities and be more difficult to detect.8

Thus far, the United States appears willing to tolerate this increased proliferation risk, but that calculus might change when Iran is able to produce enough nuclear materials for several nuclear weapons between IAEA inspections. Breaking out to produce one nuclear weapon does not provide Tehran with much of a deterrent, particularly given that it has never tested a nuclear explosive device, but producing several warheads would have greater deterrence value and pose a more serious proliferation threat.

Even so, the speed at which Iran could break out and build a nuclear weapon is a technical calculation. It does not take into account Iran’s intentions or the political factors that might drive the country to consider developing a nuclear deterrent. The U.S. intelligence community long has stated that Iran’s decision to pursue nuclear weapons will be based on a cost-benefit analysis. As of early 2022, it assessed that Tehran had not made the political decision to build a bomb or restarted key nuclear weapons-related activities.9

The factors influencing Iran’s decision-making, however, could be shifting if the regime views the widespread protests at home as a political challenge. Tehran may view the development of nuclear weapons as an option with which to preserve the existing political system, particularly if it perceives foreign countries as supporting the domestic protests.

Tehran also may gamble that the geopolitical rift caused by Russia’s war against Ukraine would mitigate the impact of UN sanctions and the diplomatic isolation that the United States and its European partners will pursue if Iran continues its nuclear expansion. The Raisi government may calculate that its support for Russia and its supply of drones for the war will insulate it partially from the global pressure campaign that preceded negotiations on the JCPOA.

Although it is still unlikely that Iran will decide to pursue nuclear weapons or withdraw from the NPT, the threat of proliferation is increasing, and this is underscoring the urgent need to stabilize Iran’s nuclear program.

Increasing Transparency

Iran’s advancing nuclear program poses two serious proliferation risks. First, Iran’s enrichment capacity and stockpiles of highly enriched uranium (HEU) allow it to break out quickly, possibly between IAEA inspections. The second risk is a longer-term concern that Iran is diverting materials from unmonitored facilities to build a covert, parallel program that could be used to develop weapons-grade uranium down the road. Given the urgency of these risks, it is important to stabilize the situation and prevent Iran from further escalating its nuclear program, thus reducing the risk of conflict and creating time and space for a more comprehensive negotiation on a long-term solution. As the JCPOA has demonstrated, reaching a new nuclear agreement could take years.

The United States could seek to mitigate these risks and buy time for future talks by offering Iran limited sanctions relief in exchange for increased monitoring over Iran’s nuclear program. Ideally, additional transparency would increase the likelihood that the IAEA would more quickly detect any Iranian attempt to break out and deter any move to divert materials, such as centrifuge components, for a covert program.

To increase the likelihood of IAEA inspectors detecting any move to produce weapons-grade uranium, Iran could reinstate daily access to uranium-enrichment facilities. The JCPOA required this level of access, but since February 2021, the frequency of IAEA inspections has been determined by Iran’s comprehensive safeguards agreement, which requires less frequent access for inspections.

The level of enrichment is one factor that helps determine the frequency of inspections. Given that Iran is now enriching uranium to 60 percent U-235, a level that no other non-nuclear-weapon state is pursuing, inspectors are visiting enrichment facilities quite regularly. The threat of an undetected breakout still exists, however, as Malley warned the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on May 25.10 Daily inspections would further mitigate that risk.

Iran also could reconnect the online enrichment monitors, a verification tool that is used to track its enrichment levels in real time. Iran disconnected these machines in June 2022 after the IAEA Board of Governors censured Iran for failing to cooperate with the agency’s safeguards investigation. Without these machines in place, IAEA sampling and analysis of uranium-enrichment levels can take up to three weeks.11 Resuming the monitoring of enrichment in real time would help inspectors determine more quickly if Iran was deviating from its stated enrichment plans and pursing uranium enrichment up to 90 percent U-235.

To deter and detect any Iranian attempts to divert materials from facilities no longer subject to IAEA inspections, Iran could allow the agency to conduct technical visits to these locations. Technical visits are voluntary access arrangements that have been used in the past when the IAEA sought access beyond what is permitted in a safeguards agreement and the state agreed.12

Another confidence-building action would be for Iran to allow the IAEA to restart camera surveillance at nuclear facilities no longer subject to inspections. In February 2021, after Iran suspended adherence to its additional protocol, which gave the IAEA access to more information and sites that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials, and JCPOA-specific transparency measures, Iran and the IAEA agreed that agency cameras would continue collecting data at certain facilities. Iran said it would give the recordings to the agency if the JCPOA was restored. Tehran’s decision to disconnect 27 of those cameras in June 2022, however, will make it difficult if not impossible for the IAEA to re-create a history of Iran’s nuclear activities during the monitoring gap.

Another confidence-building action would be for Iran to allow the IAEA to restart camera surveillance at nuclear facilities no longer subject to inspections. In February 2021, after Iran suspended adherence to its additional protocol, which gave the IAEA access to more information and sites that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials, and JCPOA-specific transparency measures, Iran and the IAEA agreed that agency cameras would continue collecting data at certain facilities. Iran said it would give the recordings to the agency if the JCPOA was restored. Tehran’s decision to disconnect 27 of those cameras in June 2022, however, will make it difficult if not impossible for the IAEA to re-create a history of Iran’s nuclear activities during the monitoring gap.

IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi warned in reports on September 7 and November 10 that because of the monitoring gap, the agency will be challenged to reestablish a baseline of Iran’s centrifuges and heavy water, even with Iran’s cooperation and the recordings from February 2021 to June 2022.13 If the IAEA cannot establish a reliable baseline, that could have serious implications for future diplomacy. It would be even more challenging for the IAEA to verify that Iran is meeting agreed limits in a restored JCPOA or a new deal.

The Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (INARA), a U.S. law passed in 2015, requires the U.S. Department of State to submit a report to Congress assessing the IAEA’s capacity to verify any nuclear agreement with Iran. The agency’s concerns about reestablishing a baseline could make that certification more difficult and provide a basis for JCPOA opponents to argue that Congress should exercise its authority under the law to block sanctions relief. Restarting the cameras and giving the IAEA regular access to the recordings could preserve space for future diplomacy while providing some assurance that Tehran is not diverting materials for a covert program.

Agreeing to additional monitoring also benefits Iran. Greater transparency would provide further assurance that Tehran’s nuclear program is peaceful, as the government claims. As Iran seeks to increase its leverage by ratcheting up its nuclear program further, it runs a greater risk of misjudging what activities might trigger a military response. Increased transparency could reduce the chance of miscalculating the proliferation threat posed by Iran’s technological advances, thus decreasing the risk of further sabotage or military action by the United States or Israel.

If Iran is willing to take voluntary steps to increase transparency, the United States must propose meaningful sanctions relief that would benefit Iran immediately. One option is to allow Iran to sell a limited amount of oil and petrochemical products every month. As with the nuclear monitoring steps, oil sales would provide an immediate benefit and could be halted quickly if Tehran suspended the voluntary verification measures. The United States also could consider unfreezing limited amounts of Iranian assets held abroad.

Longer-Term Stabilization

Increased monitoring and transparency of Iran’s nuclear program are modest steps that would mitigate the growing proliferation risk, but they are not a long-term solution for the threat posed by an unrestrained Iranian nuclear program. If the Biden administration decides that the nonproliferation benefits of the JCPOA have eroded past the point where the sanctions relief offered is sensible or that restoration of the JCPOA is too polarizing in the United States, it may prefer negotiating an entirely new nuclear agreement.

Iran too may favor such an approach, given declining support in Tehran for the JCPOA and deficiencies in the 2015 deal’s approach to sanctions relief. It also may prefer to wait until after the 2024 U.S. elections to begin negotiations on a longer-term deal. If a Republican is elected, they may withdraw again from the JCPOA, even if Iran is complying with the accord. Other frontrunners for the Republican presidential nomination have expressed similar opposition to the JCPOA, fueling concern in Tehran that even if the deal is restored, it may only last two years.

In any scenario where a new, more comprehensive deal or restoration of the 2015 JCPOA is not anticipated in the short term, voluntary measures solely aimed at increasing monitoring may not be sufficient. Increasing transparency and expanding Iran’s breakout window would stand a better chance of stabilizing the current crisis for a longer period and building time and space for negotiations on a new comprehensive nuclear agreement. This could be accomplished through an interim deal or a series of voluntary steps that include monitoring measures and limits on certain nuclear activities.

The swiftest way to increase Iran’s breakout time would be to ship out or blend down the country’s stockpiles of uranium that is enriched to 60 percent U-235 or 20 percent U-235. These stockpiles can be enriched to weapons grade (90 percent U-235) much more quickly than the 3.67 percent U-235 level to which Iran was restricted under the JCPOA. Iran, however, views these materials as its most significant source of leverage and is unlikely to give them up as part of an interim process. Nevertheless, Tehran could take certain steps to mitigate the risk posed by these materials.

One option would be for Iran to limit the amount of 60 percent- and 20 percent-enriched uranium that is stored in gas form in the country. Uranium in gas form can be injected back into centrifuges for further enrichment. Nearly all of Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium is in this form. If Iran has enough uranium enriched to these levels to use as feedstock to produce weapons-grade uranium for several nuclear weapons before the international community could respond, it could develop a more effective nuclear deterrent.

If Iran can only produce weapons-grade uranium for one nuclear weapon between inspections, that constitutes a less significant proliferation risk because one weapon provides limited security value. Capping stocks of 60 percent- and 20 percent-enriched uranium gas at this amount would increase Iran’s breakout margin, while allowing the country to retain its most significant source of leverage. The excess material could be converted to powder or stored in another country.

Enriched uranium in powder form poses less proliferation risk because it must be converted back into gas form before it can be enriched further. This process would be more challenging to complete without detection by the IAEA.

In addition to capping HEU stockpiles, an interim deal could limit Iran’s research and development activities to prevent further acquisition of new capabilities that could complicate future diplomatic efforts or further reduce the breakout window. This could include commitments by Tehran to refrain from further advanced centrifuge R&D and weaponization-related activities, such as uranium metal production and experiments relevant to designing an explosive package for a nuclear warhead. By allowing Iran to continue ongoing nuclear activities, albeit with some new restrictions in areas such as uranium stockpiling and centrifuge development, the Raisi government may be able to sell such an agreement domestically because it would not have to dismantle its nuclear infrastructure.

The Challenge of Congress

If the Biden administration succeeds in negotiating an interim deal or a series of voluntary measures with Iran, it will face a second challenge: preventing Congress from blocking sanctions relief. Under INARA, Congress has 30 days to review a nuclear deal with Iran. During that period, if the House of Representatives and the Senate pass resolutions opposing the agreement, the president is blocked from lifting sanctions on Iran.

The Democratic majority in the Senate in the next Congress increases the likelihood that the administration could prevent both chambers from passing resolutions of disapproval. Biden cannot assume, however, that the Democrats will support a new nuclear deal. Like the administration, Congress is focused on steps that the United States can take to support the Iranian protests. Even some previous JCPOA supporters are urging a pause in negotiations with Iran during the protests.

Despite shifting congressional support, Biden can make a strong argument that either an interim deal or voluntary measures would provide U.S. national security and nonproliferation benefits commensurate with limited sanctions relief and that such an arrangement is necessary to prevent escalation and buy time for a longer-term deal.

The risk of military conflict also will increase absent steps to prevent the nuclear crisis from escalating. There is little domestic appetite for the United States to become embroiled in another Middle Eastern conflict, particularly while it is helping Ukraine repel Russia, and Congress will not want to bear the blame for driving the United States into a preventable conflict. Given this, Biden should be able to garner enough congressional support to deliver sanctions relief commensurate with Iranian steps to reduce nuclear concerns.

The Drawbacks of Military Action

Although the available diplomatic options have drawbacks, they are by far preferable to military action or sabotage and stand a better chance of blocking Iran’s pathways to nuclear weapons in the long run. Kinetic action may slow the nuclear program, but as history demonstrates, Iran will respond by hardening its nuclear facilities against further attacks and by further ratcheting up its nuclear program.

In a worst-case scenario, military action could drive Iran to develop nuclear weapons covertly or withdraw from the NPT. If Tehran views nuclear weapons as the best means to prevent further attacks on its territory, the perceived security benefits of a nuclear arsenal increase.

It is also questionable how successful a military operation against Iran’s nuclear program could be, given the hardened nature of certain sites, particularly Fordow, the underground enrichment facility near Qom.

During JCPOA negotiations, the United States pushed to end enrichment at Fordow because its location deep within the mountains make it challenging if not impossible to destroy the facility using conventional weaponry. Iran restarted enrichment at that facility in November 2019 as part of its campaign to pressure the remaining parties to the JCPOA to deliver on sanctions relief.

In a study prior to the JCPOA negotiations, experts assessed that an Israeli military strike might set Iran’s nuclear ambitions back up to two years and a U.S.-led strike by up to four years.14 Those estimates are likely optimistic at this point, given that Iran has built additional, hardened facilities since then and gained additional knowledge as a result of its research activities that cannot be reversed. The U.S. intelligence community assessed in 2007 that Iran had the technical capacities to build a nuclear weapon if it decided to do so.15 Since then, Iran has not had an organized nuclear weapons program, but its uranium-enrichment capability significantly increased, and the knowledge it gained from mastering those processes cannot be bombed away.

Although military options are unlikely to be successful in blocking Iran’s pathways to the bomb in the long run, Biden probably would use military force rather than allow Iran to build a bomb during his presidency. Given the current inadequate monitoring system and Iran’s intention to continue building leverage by further advancing its nuclear program, it is increasingly likely that it could misjudge the leeway it has to maneuver and cross a line that triggers U.S. or, more likely, Israeli military action. The short window available to try and disrupt a nuclear breakout before Iran could move its nuclear material to a covert facility further increases the risk of some country prematurely using military force.

Although military options are unlikely to be successful in blocking Iran’s pathways to the bomb in the long run, Biden probably would use military force rather than allow Iran to build a bomb during his presidency. Given the current inadequate monitoring system and Iran’s intention to continue building leverage by further advancing its nuclear program, it is increasingly likely that it could misjudge the leeway it has to maneuver and cross a line that triggers U.S. or, more likely, Israeli military action. The short window available to try and disrupt a nuclear breakout before Iran could move its nuclear material to a covert facility further increases the risk of some country prematurely using military force.

In addition to pursing voluntary measures or an interim deal to increase transparency and put time back on the breakout clock, the United States and its JCPOA partners should communicate clearly to Iran what nuclear activities will trigger a military response. Given the muted international response to past escalations, such as Iran’s decision to enrich to 60 percent U-235, Iran may perceive more latitude to expand its nuclear program than actually exists. If all options are indeed on the table to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran, greater clarity about U.S. redlines could avert miscalculation.

The United States manufactured the current nuclear crisis when Trump withdrew from the JCPOA despite Iran’s compliance and over the objections of U.S. allies. Although Iran will now share the blame if the JCPOA is not restored, it would be an act of diplomatic malpractice if the Biden administration passively allows this volatile situation to continue to build. Negotiating with Iran while the regime is brutally repressing peaceful protests is not an attractive option, but an Iranian regime emboldened by nuclear weapons is a far greater threat to the Iranian people, the United States, and its allies and partners in the region. It is time for a diplomatic plan B to stabilize the cycle of nuclear escalation and create space for future diplomacy.

ENDNOTES

1. Joseph Biden, “There’s a Smarter Way to Be Tough on Iran,” CNN, September 13, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/13/opinions/smarter-way-to-be-tough-on-iran-joe-biden/index.html.

2. Stephanie Liechtenstein, “Iran Nuclear Talks Head Into Deep Freeze Ahead of Midterms,” Politico, September 9, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/09/13/iran-nuclear-talks-midterms-00056312.

3. John Irish, “No Push for Iran Nuclear Talks, U.S. Envoy Says, Due to Protests, Drone Sales,” Reuters, November 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/no-push-iran-nuclear-talks-us-envoy-says-due-protests-drone-sales-2022-11-14/.

4. “France’s Macron Does Not See Room for Progress on Iran Nuclear Deal Right Now,” Reuters, November 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/frances-macron-need-find-new-framework-over-iran-nuclear-deal-2022-11-14/.

5. Julia Masterson and Kelsey Davenport, “Assessing the Risk Posed by Iran’s Violations of the Nuclear Deal,” Arms Control Association Issue Brief, Vol. 11, No. 9 (January 29, 2020), https://www.armscontrol.org/issue-briefs/2019-12/assessing-risk-posed-iran-violations-nuclear-deal.

6. Kelsey Davenport and Julia Masterson, “The Limits of Breakout Estimates in Assessing Iran’s Nuclear Program,” Arms Control Association Issue Brief, Vol. 12, No. 6 (August 4, 2020), https://www.armscontrol.org/issue-briefs/2020-08/limits-breakout-estimates-assessing-irans-nuclear-program.

7. Trevor Findlay, “Looking Back: The Additional Protocol,” Arms Control Today, November 2007, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2007_11/Lookingback.

8. Anna Ahronheim, “Iran Is Not Getting the Bomb Any Time Soon - Military Intelligence Head,” The Jerusalem Post, October 3, 2021, https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/iran-news/head-of-military-intelligence-iran-not-getting-the-bomb-any-time-soon-680853.

9. U.S. Department of State, “Adherence to and Compliance With Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments,” April 2022, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/2022-Adherence-to-and-Compliance-with-Arms-Control-Nonproliferation-and-Disarmament-Agreements-and-Commitments-1.pdf; Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” February 2022, https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/reports-publications/reports-publications-2022/item/2279-2022-annual-threat-assessment-of-the-u-s-intelligence-community.

10. Robert Malley, “The JCPOA Negotiations and the United States’ Policy on Iran Moving Forward,” May 25, 2022, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/the-jcpoa-negotiations-and-united-states-policy-on-iran-moving-forward05252201.

11. Vincent Fournier and Miklos Gaspar, “New IAEA Uranium Enrichment Monitor to Verify Iran’s Commitments Under JCPOA,” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Office of Public Information and Communication, January 16, 2016, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/new-iaea-uranium-enrichment-monitor-verify-iran’s-commitments-under-jcpoa.

12. John Carlson, “Special Inspections Revisited” (paper presented to Annual Meeting of the Institute of Nuclear Materials Management, Phoenix, Arizona, July 10–14, 2005), https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/uploads/INMM2005SpecialInspections.pdf.

13. IAEA, “NPT Safeguards Agreement With the Islamic Republic of Iran: Report by the Director General,” September 7, 2022, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/22/09/gov2022-42.pdf.

14. The Iran Project, “Weighing the Benefits and Costs of Military Action Against Iran,” 2012, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/event/IranReport_091112_ExecutiveSummary.pdf.

15. “Iran: Nuclear Intentions and Capabilities,” November 2007, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Reports%20and%20Pubs/20071203_release.pdf.

Kelsey Davenport is director for nonproliferation policy at the Arms Control Association.

The broad, ambiguous nuclear declaratory policy in the 2022 NPR walks back Biden’s pledge to narrow the role of U.S. nuclear weapons. In 2020 he wrote “that the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal should be deterring and, if necessary, retaliating against a nuclear attack. As president, I will work to put that belief into practice, in consultation with the U.S. military and U.S. allies.” As far back as 1990, Biden, then a U.S. senator, argued that the “military rationale for ‘first use’ has disappeared.”

The broad, ambiguous nuclear declaratory policy in the 2022 NPR walks back Biden’s pledge to narrow the role of U.S. nuclear weapons. In 2020 he wrote “that the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal should be deterring and, if necessary, retaliating against a nuclear attack. As president, I will work to put that belief into practice, in consultation with the U.S. military and U.S. allies.” As far back as 1990, Biden, then a U.S. senator, argued that the “military rationale for ‘first use’ has disappeared.”

Tragically, time nearly has run out to achieve this commitment. If Biden does not start exploring other options to stabilize the growing nuclear crisis, the United States could have to contend with an Iranian regime on the brink of possessing nuclear weapons or with a conflict to prevent it.

Tragically, time nearly has run out to achieve this commitment. If Biden does not start exploring other options to stabilize the growing nuclear crisis, the United States could have to contend with an Iranian regime on the brink of possessing nuclear weapons or with a conflict to prevent it. Another confidence-building action would be for Iran to allow the IAEA to restart camera surveillance at nuclear facilities no longer subject to inspections. In February 2021, after Iran suspended adherence to its additional protocol, which gave the IAEA access to more information and sites that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials, and JCPOA-specific transparency measures, Iran and the IAEA agreed that agency cameras would continue collecting data at certain facilities. Iran said it would give the recordings to the agency if the JCPOA was restored. Tehran’s decision to disconnect 27 of those cameras in June 2022, however, will make it difficult if not impossible for the IAEA to re-create a history of Iran’s nuclear activities during the monitoring gap.

Another confidence-building action would be for Iran to allow the IAEA to restart camera surveillance at nuclear facilities no longer subject to inspections. In February 2021, after Iran suspended adherence to its additional protocol, which gave the IAEA access to more information and sites that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials, and JCPOA-specific transparency measures, Iran and the IAEA agreed that agency cameras would continue collecting data at certain facilities. Iran said it would give the recordings to the agency if the JCPOA was restored. Tehran’s decision to disconnect 27 of those cameras in June 2022, however, will make it difficult if not impossible for the IAEA to re-create a history of Iran’s nuclear activities during the monitoring gap. Although military options are unlikely to be successful in blocking Iran’s pathways to the bomb in the long run, Biden probably would use military force rather than allow Iran to build a bomb during his presidency. Given the current inadequate monitoring system and Iran’s intention to continue building leverage by further advancing its nuclear program, it is increasingly likely that it could misjudge the leeway it has to maneuver and cross a line that triggers U.S. or, more likely, Israeli military action. The short window available to try and disrupt a nuclear breakout before Iran could move its nuclear material to a covert facility further increases the risk of some country prematurely using military force.

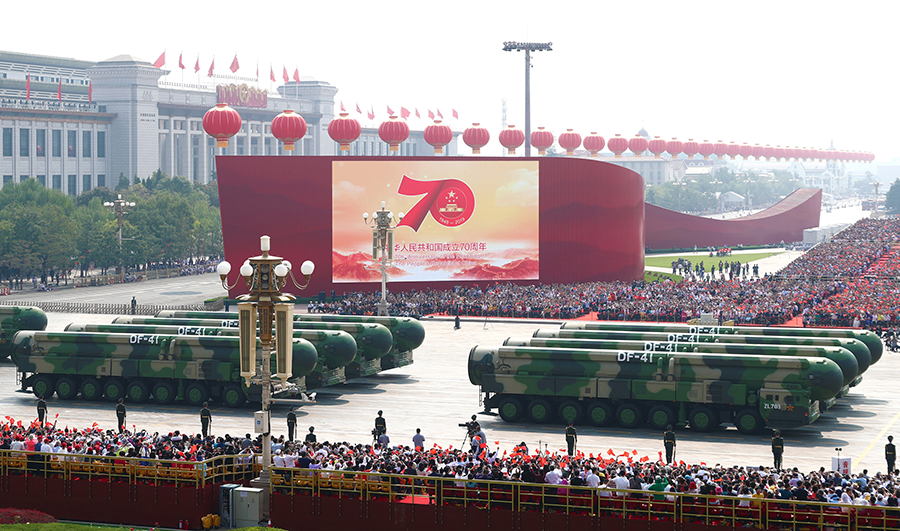

Although military options are unlikely to be successful in blocking Iran’s pathways to the bomb in the long run, Biden probably would use military force rather than allow Iran to build a bomb during his presidency. Given the current inadequate monitoring system and Iran’s intention to continue building leverage by further advancing its nuclear program, it is increasingly likely that it could misjudge the leeway it has to maneuver and cross a line that triggers U.S. or, more likely, Israeli military action. The short window available to try and disrupt a nuclear breakout before Iran could move its nuclear material to a covert facility further increases the risk of some country prematurely using military force. With China’s constructive participation, it will be much easier to manage challenges to international arms control and the international order, such as those posed by Iran and North Korea. Efforts to further develop the multilateral arms control architecture also will be more effective and sustainable if Beijing is on board.

With China’s constructive participation, it will be much easier to manage challenges to international arms control and the international order, such as those posed by Iran and North Korea. Efforts to further develop the multilateral arms control architecture also will be more effective and sustainable if Beijing is on board. Second, engagement should be as issue specific as possible. The field of disarmament and arms control has evolved and become so multifaceted and differentiated that the general demand for Chinese involvement rings hollow. Although interconnections between topics cannot be completely ignored, for example, with regard to issues involving disarmament and nonproliferation, there is a risk of weighing down talks with too many linkages.

Second, engagement should be as issue specific as possible. The field of disarmament and arms control has evolved and become so multifaceted and differentiated that the general demand for Chinese involvement rings hollow. Although interconnections between topics cannot be completely ignored, for example, with regard to issues involving disarmament and nonproliferation, there is a risk of weighing down talks with too many linkages. Such an incongruous policy can have implications for multilateral arms control. For decades, Pakistan has been blocking the start of negotiations on a treaty prohibiting the production of weapons-grade fissile material at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. Islamabad ostensibly has conditioned its consent on including New Delhi’s stockpiles of fissile material in any future treaty, but many observers wonder whether Beijing may be encouraging such stonewalling to prevent future limits on its own nuclear weapons.

Such an incongruous policy can have implications for multilateral arms control. For decades, Pakistan has been blocking the start of negotiations on a treaty prohibiting the production of weapons-grade fissile material at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. Islamabad ostensibly has conditioned its consent on including New Delhi’s stockpiles of fissile material in any future treaty, but many observers wonder whether Beijing may be encouraging such stonewalling to prevent future limits on its own nuclear weapons. Although Liberal leaders generally have advocated reductions in the numbers of nuclear weapons held by all nuclear-weapon states and adhered to Australian participation in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), their approach has been somewhat paradoxical. In this regard, Australia has not forthrightly challenged the utility, value, legality, and legitimacy of nuclear weapons nor questioned the logic and practice of nuclear deterrence. Notwithstanding the 2021 pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States known as AUKUS, Australia has left nuclear agency predominantly in the hands of the states that possess nuclear weapons, compliantly accepting that this group can safely manage nuclear risks through appropriate adjustments to warhead numbers, nuclear doctrines, and force postures.

Although Liberal leaders generally have advocated reductions in the numbers of nuclear weapons held by all nuclear-weapon states and adhered to Australian participation in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), their approach has been somewhat paradoxical. In this regard, Australia has not forthrightly challenged the utility, value, legality, and legitimacy of nuclear weapons nor questioned the logic and practice of nuclear deterrence. Notwithstanding the 2021 pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States known as AUKUS, Australia has left nuclear agency predominantly in the hands of the states that possess nuclear weapons, compliantly accepting that this group can safely manage nuclear risks through appropriate adjustments to warhead numbers, nuclear doctrines, and force postures. Not surprisingly, many of the concerns articulated by local and international experts during the AUKUS initiative’s first year will persist deep into Albanese’s tenure in office. The first controversial development emanating from it was the clumsy diplomacy demonstrated when Australia precipitously canceled its planned purchase of Attack-class submarines from France so that it could buy nuclear-powered submarines from the UK and the United States. Although the financial compensation for terminating this program—$568 million paid by Canberra to the French-owned Naval Group—has been settled and recent diplomatic visits to Paris by Albanese and Marles have quelled the acrimony, the total cost of the abandoned program will be approximately $2.3 billion. Aside from the economic fallout, many questions remain unanswered, including those relating to the logistics, gaps in capability, and extent to which Australia will be able to meet its NPT obligations.

Not surprisingly, many of the concerns articulated by local and international experts during the AUKUS initiative’s first year will persist deep into Albanese’s tenure in office. The first controversial development emanating from it was the clumsy diplomacy demonstrated when Australia precipitously canceled its planned purchase of Attack-class submarines from France so that it could buy nuclear-powered submarines from the UK and the United States. Although the financial compensation for terminating this program—$568 million paid by Canberra to the French-owned Naval Group—has been settled and recent diplomatic visits to Paris by Albanese and Marles have quelled the acrimony, the total cost of the abandoned program will be approximately $2.3 billion. Aside from the economic fallout, many questions remain unanswered, including those relating to the logistics, gaps in capability, and extent to which Australia will be able to meet its NPT obligations. Albanese will be in a better position to address lingering questions about the AUKUS pact when the government’s nuclear-powered submarine task force makes recommendations in March 2023. For instance, on a logistical level, the task force is expected to determine whether Australia will go with the UK Astute-class submarine, the U.S. Virginia-class nuclear submarine, or another version shared by all three states. The conclusions of this preliminary consultation phase should also illuminate the specific details of a submarine built domestically, what submarine the government proposes as an interim capability, and any additional proposals to address any AUKUS workforce requirements.

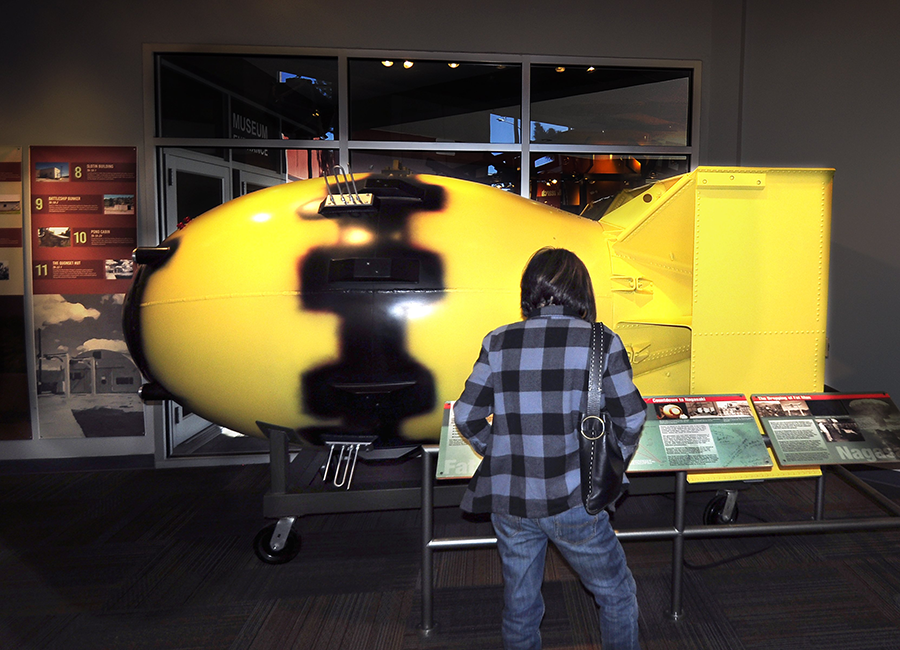

Albanese will be in a better position to address lingering questions about the AUKUS pact when the government’s nuclear-powered submarine task force makes recommendations in March 2023. For instance, on a logistical level, the task force is expected to determine whether Australia will go with the UK Astute-class submarine, the U.S. Virginia-class nuclear submarine, or another version shared by all three states. The conclusions of this preliminary consultation phase should also illuminate the specific details of a submarine built domestically, what submarine the government proposes as an interim capability, and any additional proposals to address any AUKUS workforce requirements. If nuclear weapons are ever eliminated, it will be the result of actions big and small at every communal level, from international leaders to civil society. The Reverend John C. Wester occupies a unique role in this continuum as the Roman Catholic archbishop of Santa Fe, whose archdiocese is home to the Los Alamos and Sandia national nuclear laboratories and site of the first Manhattan Project nuclear tests. In January, Wester issued a pastoral letter, “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation Toward Nuclear Disarmament,” which called for the abolition of nuclear weapons and declared that the archdiocese “must be part of a strong peace initiative.” He had a compelling basis for action: In 2021, Pope Francis shifted the church’s position from accepting deterrence as a legitimate rationale for nuclear weapons to decrying the possession of nuclear weapons as “immoral.” Even with the pope’s admonition, however, Wester is finding his peace initiative slow going. He discussed his efforts with Carol Giacomo, editor of Arms Control Today. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If nuclear weapons are ever eliminated, it will be the result of actions big and small at every communal level, from international leaders to civil society. The Reverend John C. Wester occupies a unique role in this continuum as the Roman Catholic archbishop of Santa Fe, whose archdiocese is home to the Los Alamos and Sandia national nuclear laboratories and site of the first Manhattan Project nuclear tests. In January, Wester issued a pastoral letter, “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation Toward Nuclear Disarmament,” which called for the abolition of nuclear weapons and declared that the archdiocese “must be part of a strong peace initiative.” He had a compelling basis for action: In 2021, Pope Francis shifted the church’s position from accepting deterrence as a legitimate rationale for nuclear weapons to decrying the possession of nuclear weapons as “immoral.” Even with the pope’s admonition, however, Wester is finding his peace initiative slow going. He discussed his efforts with Carol Giacomo, editor of Arms Control Today. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. One thing led to another, and we ended up writing a pastoral letter. I thought this is exactly what I should do as the archbishop of Santa Fe, where all these nuclear weapons programs started. Santa Fe has to have a place at the table discussing those issues. Then I started reading up, including some things that are in favor of dropping the bomb in World War II, just so I can hear more from the other side. I don't want to be myopic on it. I'm on a steep learning curve, and I'm doing my best to get it because my whole intent is to keep the conversation going further. We have to keep talking about this until one day we can really rid the world of nuclear weapons.

One thing led to another, and we ended up writing a pastoral letter. I thought this is exactly what I should do as the archbishop of Santa Fe, where all these nuclear weapons programs started. Santa Fe has to have a place at the table discussing those issues. Then I started reading up, including some things that are in favor of dropping the bomb in World War II, just so I can hear more from the other side. I don't want to be myopic on it. I'm on a steep learning curve, and I'm doing my best to get it because my whole intent is to keep the conversation going further. We have to keep talking about this until one day we can really rid the world of nuclear weapons. Wester: Yes. We are going to. We had quite a few date possibilities this last summer. I was going to meet with scientists in the Los Alamos labs, and we're still going to do it, we just could not come up with a date, I suppose because of the vacations and all. So, I want to have that conversation. I have gotten some responses from some engineers and scientists at Sandia and Los Alamos that have been positive. They've said they agree with the pastoral letter. They read the summary of it at least, and they do agree with its ultimate desire to rid the world of nuclear arms. But my sense is that they think that we have quite a few steps to take before we get there. It's hedging their bets maybe. We've already waited too long. There are 13,000 weapons in the world today, with more being produced. Several countries are modernizing their weapons, including with hypersonic delivery systems, and all this portends badly for the future.

Wester: Yes. We are going to. We had quite a few date possibilities this last summer. I was going to meet with scientists in the Los Alamos labs, and we're still going to do it, we just could not come up with a date, I suppose because of the vacations and all. So, I want to have that conversation. I have gotten some responses from some engineers and scientists at Sandia and Los Alamos that have been positive. They've said they agree with the pastoral letter. They read the summary of it at least, and they do agree with its ultimate desire to rid the world of nuclear arms. But my sense is that they think that we have quite a few steps to take before we get there. It's hedging their bets maybe. We've already waited too long. There are 13,000 weapons in the world today, with more being produced. Several countries are modernizing their weapons, including with hypersonic delivery systems, and all this portends badly for the future.

The author then tests her theoretical explanation of why states adhere to the various nonproliferation agreements by using case studies representing multiple steps in the construction of the regime. She examines how the United States acted to bring Japan, Indonesia, Egypt, and Cuba into NPT membership, showcasing the range of the hegemon’s tools across a range of states with varying degrees of embeddedness in the U.S.-led international order. Next, the U.S. global campaign to indefinitely extend the NPT in 1995 is viewed through the lenses of Japan, Indonesia, South Africa, and Egypt. Finally, Gibbons details U.S. efforts to promote adoption by Japan, Indonesia, and (unsuccessfully) Egypt of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Model Additional Protocol.

The author then tests her theoretical explanation of why states adhere to the various nonproliferation agreements by using case studies representing multiple steps in the construction of the regime. She examines how the United States acted to bring Japan, Indonesia, Egypt, and Cuba into NPT membership, showcasing the range of the hegemon’s tools across a range of states with varying degrees of embeddedness in the U.S.-led international order. Next, the U.S. global campaign to indefinitely extend the NPT in 1995 is viewed through the lenses of Japan, Indonesia, South Africa, and Egypt. Finally, Gibbons details U.S. efforts to promote adoption by Japan, Indonesia, and (unsuccessfully) Egypt of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Model Additional Protocol. Ploughshares and Swords: India's Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War

Ploughshares and Swords: India's Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War The Nuclear Club: How America and the World Policed the Atom from Hiroshima to Vietnam

The Nuclear Club: How America and the World Policed the Atom from Hiroshima to Vietnam The IAEA board on Nov. 17 passed a resolution condemning Iran for its continued failure to cooperate with a years-long investigation into past nuclear activities that should have been declared under Iran’s legally binding safeguards agreement. Prior to the vote, the IAEA reported that there was no progress on the investigation despite two meetings between Iranian and IAEA officials in September and November.

The IAEA board on Nov. 17 passed a resolution condemning Iran for its continued failure to cooperate with a years-long investigation into past nuclear activities that should have been declared under Iran’s legally binding safeguards agreement. Prior to the vote, the IAEA reported that there was no progress on the investigation despite two meetings between Iranian and IAEA officials in September and November. The Nov. 2 drill involved short-range ballistic and surface-to-air missile systems. The day-long barrages were designed to simulate a “strike on the enemy’s air force base” and demonstrate North Korea’s ability to “annihilate air targets at different altitudes and distances,” according to a report from the General Staff of the Korean People’s Army.

The Nov. 2 drill involved short-range ballistic and surface-to-air missile systems. The day-long barrages were designed to simulate a “strike on the enemy’s air force base” and demonstrate North Korea’s ability to “annihilate air targets at different altitudes and distances,” according to a report from the General Staff of the Korean People’s Army. The new assessment by the U.S. National Intelligence Council has led to differing interpretations. Some Biden administration officials believe the Russian discussions might signal genuine consideration of nuclear use on the Ukrainian battlefield, where Russia has sustained huge losses, while others believe the discussions do not imply intent at this stage.

The new assessment by the U.S. National Intelligence Council has led to differing interpretations. Some Biden administration officials believe the Russian discussions might signal genuine consideration of nuclear use on the Ukrainian battlefield, where Russia has sustained huge losses, while others believe the discussions do not imply intent at this stage.