December 2022

By Shannon Bugos

The Biden administration finally released its long-awaited Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which maintains its predecessor’s focus on China and Russia as the top U.S. adversaries but largely reverts to the Obama era with a narrower declaratory policy and strong support for future arms control efforts.

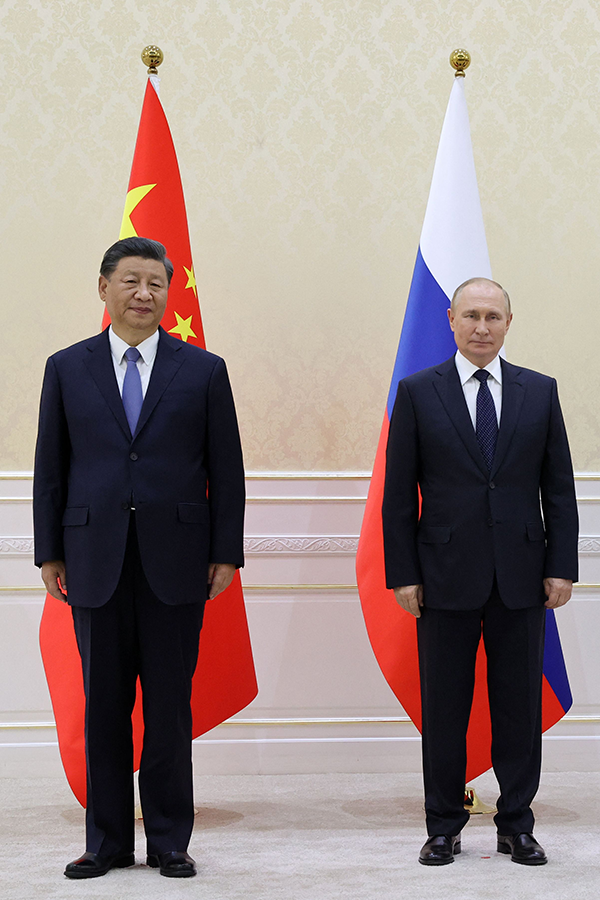

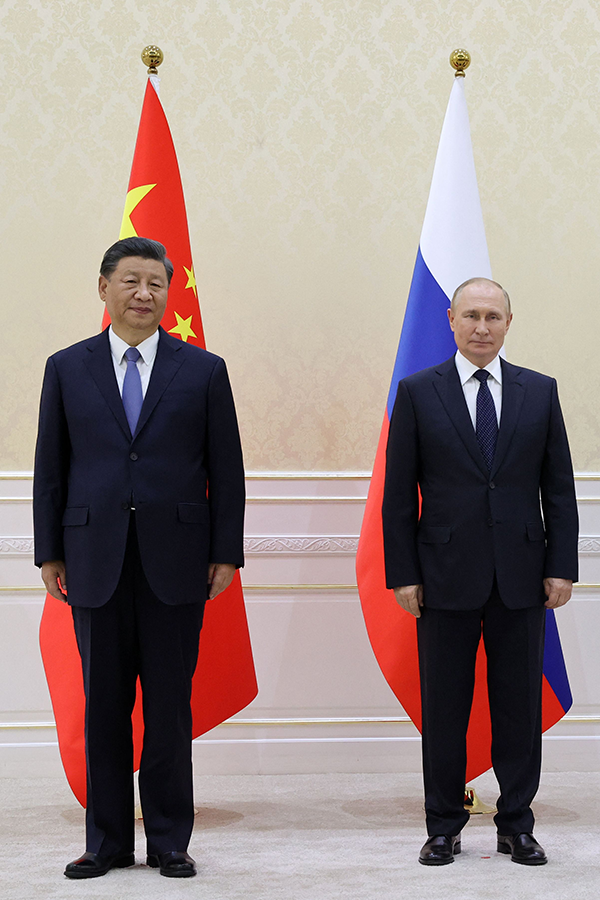

“By the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries,” states the Biden administration NPR, referring to China and Russia. “This will create new stresses on stability and new challenges for deterrence, assurance, arms control, and risk reduction.”

“By the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries,” states the Biden administration NPR, referring to China and Russia. “This will create new stresses on stability and new challenges for deterrence, assurance, arms control, and risk reduction.”

Richard Johnson, deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear and countering weapons of mass destruction policy, oversaw the administration’s review of U.S. nuclear policy, filling in after the ousting last year of Leonor Tomero. (See ACT, December 2021.)

“One of the most important aspects of this 2022 NPR is that we see it as comprehensive, and we see it as balanced,” Johnson said on Nov. 1. “There is just as much discussion in this document about the importance of nuclear deterrence, about our modernization of our nuclear triad, and also about things like arms control, risk reduction, strategic stability—all things that this administration…[wants] to regain the leadership role in.”

The Pentagon released the NPR and the Missile Defense Review on Oct. 27 as components of the department’s overall National Defense Strategy. The White House publicly released its National Security Strategy, which set the guidelines for the Pentagon’s documents, earlier in the month. (See ACT, November 2022.)

The White House transmitted the classified version of the National Defense Strategy to Congress in March, a month after Russia invaded Ukraine. (See ACT, April 2022.) The invasion, according to media reports, prompted the Pentagon to rewrite at least portions of the document and likely delayed its publication.

It casts China as “the most comprehensive and serious challenge” and Russia “as an acute threat.” To simultaneously deter both countries, the United States must continue modernizing the U.S. nuclear triad and infrastructure and reinforcing U.S. extended deterrence commitments, according to the strategy.

Last year, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the United States will spend $634 billion over the next 10 years to sustain and modernize its nuclear arsenal. (See ACT, June 2021.) The Pentagon’s top priority and most expensive modernization programs include the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, the B-21 Raider strategic bomber, and the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile.

At the same time, the Biden administration has committed equally to “pursue a comprehensive and balanced approach that places a renewed emphasis on arms control, nonproliferation, and risk reduction to strengthen stability, head off costly arms races, and signal our desire to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons globally,” the NPR states.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “underscores that nuclear dangers persist and could grow,” the review states. Russian President Vladimir Putin has “conducted aggression against Ukraine under a nuclear shadow characterized by irresponsible saber-rattling, out of cycle nuclear exercises, and false narratives concerning the potential use of weapons of mass destruction,” it declares.

Given the size, diversity, and modernization of its nuclear arsenal, Russia remains a focus of U.S. arms control efforts. In February 2021, Putin and U.S. President Joe Biden extended for five years the last remaining U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control treaty, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). (See ACT, March 2021.)

Moving forward, the review says, the Biden administration stands “ready to expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START when it expires in 2026, although negotiation requires a willing partner operating in good faith.” The U.S. Department of State paused the bilateral strategic stability dialogue on arms control after Russia invaded Ukraine. Whether the dialogue resumes or the two countries will launch a separate, more formal arms control negotiation forum remains unclear.

Any future Russian-U.S. arms control processes increasingly will need to account for China’s nuclear arsenal, the NPR advises. Beijing has refused thus far to engage on the issue. Even so, the Biden administration remains ready to talk with China in bilateral and multilateral forums on “a full range of strategic issues, with a focus on military de-confliction, crisis communications, information sharing, mutual restraint, risk reduction, emerging technologies, and approaches to nuclear arms control.”

The ongoing P5 process, in which the recognized nuclear-weapon states under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) meet to discuss their unique responsibilities under the treaty, also could be a venue for efforts “to deepen engagement on nuclear doctrines, concepts for strategic risk reduction, and nuclear arms control verification,” the review states.

Despite Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign pledge to adopt a “sole purpose” nuclear policy, the NPR emphasized the “fundamental role” of nuclear weapons. (See ACT, April 2022.)

“The fundamental role of nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners,” the Biden NPR states, mirroring the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR. (See ACT, May 2010.) The policy was a disappointment within the arms control community, where many experts argue that a sole-purpose policy is a stronger declaration that the one and only role of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter and, if necessary, retaliate against a nuclear strike.

“The fundamental role of nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners,” the Biden NPR states, mirroring the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR. (See ACT, May 2010.) The policy was a disappointment within the arms control community, where many experts argue that a sole-purpose policy is a stronger declaration that the one and only role of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter and, if necessary, retaliate against a nuclear strike.

Although the Biden review differs from the Trump administration’s 2018 NPR, which asserted a more expansive declaratory policy and lackluster support for arms control, the Biden NPR allows the Pentagon to keep a new low-yield warhead requested four years ago. The Trump administration wanted the low-yield W76-2 warhead, which the Navy deployed on some of its submarine-launched ballistic missiles in late 2019, to fill a perceived gap in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. (See ACT, March 2020.)

But the Biden administration reversed course on two other nuclear capabilities, and as a result, the 2022 review reflected the cancellation of the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile and the retirement of the megaton class B83-1 gravity bomb. The Trump NPR attempted to reintroduce the former to the Navy and to postpone the retirement of the latter. (See ACT, March 2018.)

The Pentagon’s National Defense Strategy revolves around the concept of integrated deterrence, which also includes missile defense systems, as they “add resilience and undermine adversary confidence in missile use,” the 2022 Missile Defense Review states.

The Biden administration decided to maintain its predecessor’s approach of pursuing long-range missile defenses against possible limited nuclear ballistic missile attacks from North Korea or Iran and to rely on nuclear deterrence to defend against the larger, more sophisticated Russian and Chinese nuclear arsenals.

The Missile Defense Review made clear the Biden administration’s intention to move forward with developing the Next Generation Interceptor missile for the U.S. homeland defense system and “active and passive” hypersonic defense programs.

The document only vaguely references the Pentagon’s concept of a “layered” homeland missile defense architecture, which has faced much skepticism from Congress and the Government Accountability Office. For the first time in three years, the Department of Defense requested no funding for this system in fiscal year 2023 and specified no plans for future funding, likely signaling the administration’s desire to end the effort.

The review acknowledges “the interrelationship between strategic offensive arms and strategic defensive systems,” which stands as a notable statement for arms control. “Strengthening mutual transparency and predictability with regard to these systems could help reduce the risk of conflict,” according to the review. Future Russian-U.S. nuclear arms control likely will be impossible without Washington putting missile defense systems on the table for discussion, which it has long resisted. With this statement in the review, the Biden administration perhaps has hinted that it may contemplate some initial risk reduction measures with respect to U.S. missile defense systems.

Following its 2022 summit in Indonesia, the G-20 issued a statement on Nov. 16 saying that “most members strongly condemned the war in Ukraine and stressed it is causing immense human suffering and exacerbating existing fragilities in the global economy.”

Following its 2022 summit in Indonesia, the G-20 issued a statement on Nov. 16 saying that “most members strongly condemned the war in Ukraine and stressed it is causing immense human suffering and exacerbating existing fragilities in the global economy.” “By the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries,” states the Biden administration NPR, referring to China and Russia. “This will create new stresses on stability and new challenges for deterrence, assurance, arms control, and risk reduction.”

“By the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries,” states the Biden administration NPR, referring to China and Russia. “This will create new stresses on stability and new challenges for deterrence, assurance, arms control, and risk reduction.” “The fundamental role of nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners,” the Biden NPR states, mirroring the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR. (See

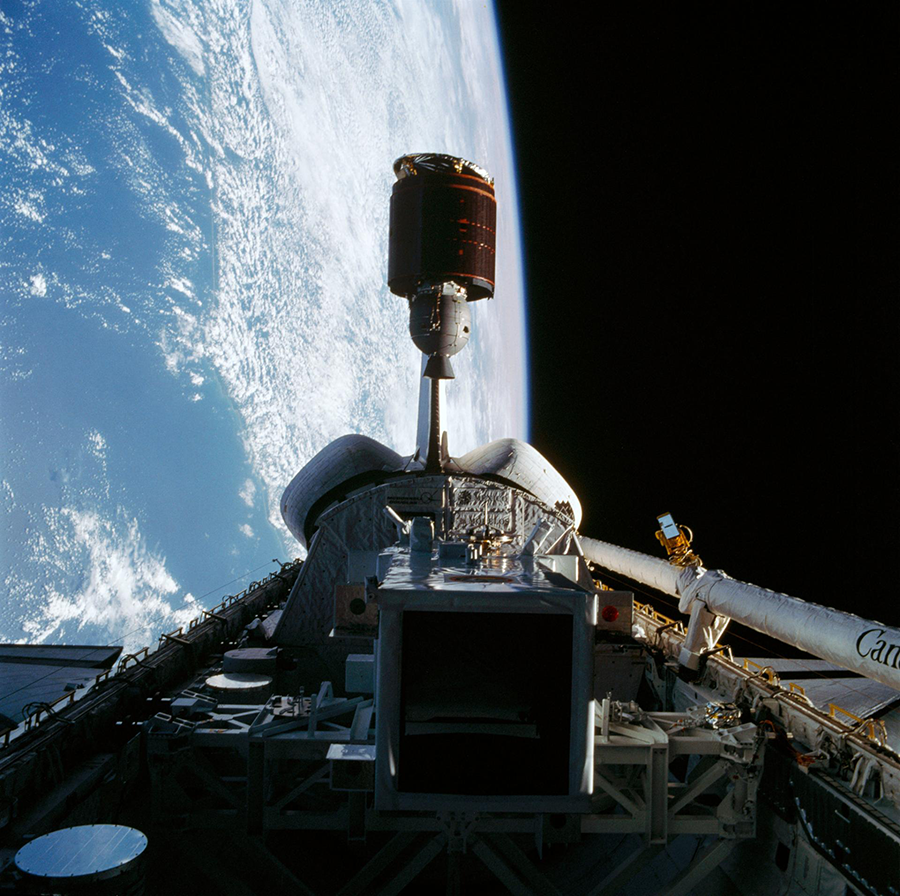

“The fundamental role of nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners,” the Biden NPR states, mirroring the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR. (See  Although not legally binding, the resolution reflects an increase in international political support for prohibiting ASAT weapons testing that destroy objects in space, which is formally referenced as “destructive direct-ascent anti-missile testing.”

Although not legally binding, the resolution reflects an increase in international political support for prohibiting ASAT weapons testing that destroy objects in space, which is formally referenced as “destructive direct-ascent anti-missile testing.” “We are fully aware that the journey to reach our objective is a very challenging one, but I am convinced that with a strong political will and commitment, we can achieve progress with collective dedication, wisdom and hard work,” Chair Jeanne Mrad of Lebanon said on Nov. 18, according to a UN statement.

“We are fully aware that the journey to reach our objective is a very challenging one, but I am convinced that with a strong political will and commitment, we can achieve progress with collective dedication, wisdom and hard work,” Chair Jeanne Mrad of Lebanon said on Nov. 18, according to a UN statement. Experts said the test is evidence that Turkey is continuing to make progress with its indigenous missile program and will be less dependent on external suppliers such as the United States, but that does not mean the Tayfun will enter service soon.

Experts said the test is evidence that Turkey is continuing to make progress with its indigenous missile program and will be less dependent on external suppliers such as the United States, but that does not mean the Tayfun will enter service soon. The exact missile type used in the test is unknown, but some experts believe it was the K-15 missile or the K-4 missile. The K-15 missile is estimated to have a range of 700 kilometers, which could reach parts of Pakistan, while the K-4 missile has an estimated range of 3,500 kilometers, which could reach China. (See

The exact missile type used in the test is unknown, but some experts believe it was the K-15 missile or the K-4 missile. The K-15 missile is estimated to have a range of 700 kilometers, which could reach parts of Pakistan, while the K-4 missile has an estimated range of 3,500 kilometers, which could reach China. (See