May 2023

By Rachel Stohl, Loren Voss, and Elias Yousif

The United States accounts for 40 percent of the global arms trade, a greater market share than the next four closest competitors combined, including Russia and China.1

Although many of the tens of thousands of weapons that Washington exports abroad each year flow to like-minded partners with commendable human rights records, many end up in the hands of governments engaged in conflict, accused of civil and human rights abuses, or found to be undermining U.S. interests. Such transfers have long cast a shadow on the U.S. commitment to international human rights and raised questions as to the wisdom and morality of enabling the predatory or destabilizing behaviors of questionable partners.

Although many of the tens of thousands of weapons that Washington exports abroad each year flow to like-minded partners with commendable human rights records, many end up in the hands of governments engaged in conflict, accused of civil and human rights abuses, or found to be undermining U.S. interests. Such transfers have long cast a shadow on the U.S. commitment to international human rights and raised questions as to the wisdom and morality of enabling the predatory or destabilizing behaviors of questionable partners.

Two critical elements in the Biden administration’s new conventional arms transfer policy have the potential to chip away at this dilemma and reshape the U.S. approach to arms transfers, with an explicit emphasis on restraint and a higher human rights standard for arms transfer assessments.2 These are laudable ambitions, but achieving them will not be easy. Engendering an ethos of restraint in U.S. arm transfers will require confronting long-held misconceptions about the strategic risks of restricting transfers to questionable partners, while implementing a higher human rights standard requires a far more robust information ecosystem and analytical process for decision-makers.

Shaping Arms Transfers

An arms transfer policy is established by a presidential directive intended to outline the key aims and considerations that shape the whole-of-government approach to arms transfers. In addition to defining the priorities and criteria for security cooperation decision-making, the policy is a tone-setting document, sending a signal across the government and beyond regarding the spirit of the U.S. approach to arms sales and the role of arms sales in foreign policy and national security objectives.

Although the policy has been rewritten three times in the last nine years, prior to 2014 no update had been made since the Clinton administration in 1995. The Obama administration’s policy, which was the first rewrite in nearly two decades, was seen as an effort to align the U.S. approach to arms transfers with new geopolitical and geostrategic considerations in the post-Cold War world and to meet the imperatives of the global war on terrorism better.

The Trump administration’s 2018 policy emphasized counterterrorism and nonproliferation priorities that reflected a continued focus on efforts to defeat al Qaeda and associated groups, but it also made a dramatic shift toward a more economically oriented “Buy American” and “America First” approach. It placed economic security considerations front and center, even more than its predecessors, and sought to enable the U.S. government to sell more weapons more quickly with less restraint and less conditionality. The policy made an important contribution by addressing civilian harm for the first time by establishing that the executive branch had a policy of facilitating ally and partner efforts to reduce the risk of national or coalition operations causing civilian harm. Nevertheless, the prioritization of economic considerations helped justify a number of arms sales that defied human rights and civilian protection concerns, as well as public and congressional opposition, including highly controversial sales to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia in 2019.3

With the aim of distinguishing its human rights commitments from those of its predecessor, the Biden administration made clear that a revised policy that rightsized human rights considerations was one of its early priorities, something that was keenly anticipated by the arms control and human rights communities. Although there are many welcome updates in the new policy, the commitment to restraint and the announcement of a higher human rights standard that will apply to arms transfers are among its most notable developments.4

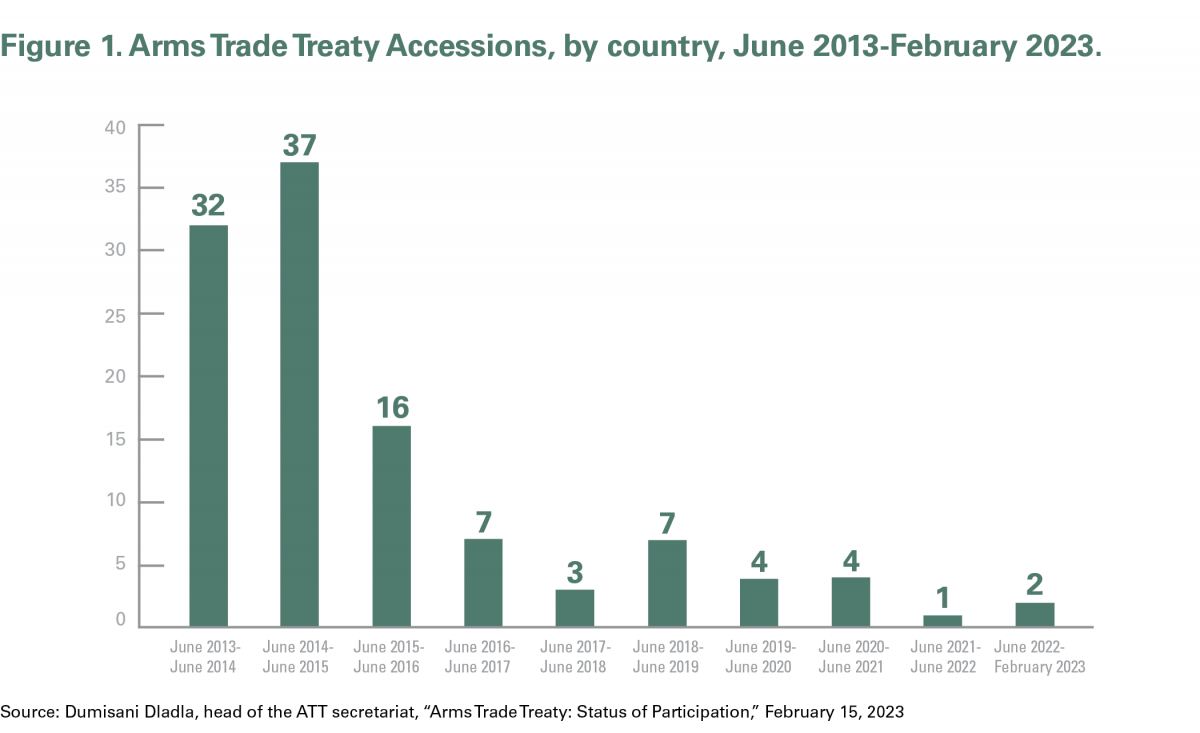

Relatedly, the administration promised that a change to the current U.S. position rejecting the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which establishes common standards for the international trade of conventional weapons and seeks to reduce the illicit arms trade, would result from a new conventional arms transfer policy. Unfortunately, the new policy has not clarified the U.S. position or resulted in renewed engagement with the ATT.

|

Definitions of Civilian Harm and Protection of Civilians

Civilian Harm includes conflict-related death, physical and psychological injury, loss of property and livelihood, and interruption of access to essential services.*

Civilian Casualties is a more narrowly focused term referring to deaths and injuries of civilians by armed conflict.

Protection of Civilians is a broader term that includes all efforts to reduce civilian risks from physical violence, secure their rights to access essential services and resources, and contribute to a secure, stable, and just environment for civilians over the long term.**

*Sahr Muhammedally, “A Primer on Civilian Harm Mitigation in Urban Operations,” Center for Civilians in Conflict, June 2022.

**U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute, “Protection of Civilians Military Reference Guide, Second Edition,” January 2018.

|

The ‘If We Don’t Sell, Someone Else Will’ Paradigm

The Biden administration’s commitment to restraint in the U.S. approach to security cooperation is likely to be met with a familiar rebuttal: “If we don’t sell them arms, someone else will.” This well-worn refrain reflects a long-standing assumption in U.S. security cooperation policy that countries cut off from the U.S. arms trade will turn quickly to other suppliers, including U.S. adversaries, for their defense needs, thereby eroding a key source of U.S. global influence. Recent analysis suggests, however, that this argument, which frequently has been used to justify arms transfers to countries engaged in human rights abuses or behaviors contrary to U.S. interests, fails to account for the complex set of circumstances that shape decision-making by arms importers.5 If the Biden administration is serious about its commitment to restraint, it must dispel misconceptions embodied by the “if we don’t sell” myth that distort policy choices and encourage an ever more permissive approach to arms transfers.

The global arms trade is far from an abundant buyer’s market, and an importer's historic preference for a given patron creates a degree of dependency that adds risks and costs to seeking alternative suppliers or diversifying its sources for materiel. Although countries have elected to incur those risks and costs in some cases, the factors shaping those decisions are far more complex than implied by “if we don’t sell.”

Simply sourcing a comparable capability can be challenging, especially for highly sophisticated systems such as advanced aircraft or air defense systems. Domestic production may be technically or financially beyond reach or logistically impractical, importers may face a coordinated policy of denial among allied exporters, and producers may be few in number or belong to incompatible geopolitical or ideological blocs. Similarly, integrating new systems into existing defense architectures introduces new burdens on importers, requiring costly capital investments in parallel or alternative logistics, training, sustainment, and doctrine.

In many cases, the nature of the importer's immediate security environment can add to the risks and costs of seeking alternative suppliers. For countries facing acute security threats, the time and potential readiness gaps associated with adopting and integrating alternative platforms or pivoting away from a primary supplier could jeopardize defense planning imperatives or interoperability with a preferred partner.

Beyond the practical concerns, important political and diplomatic considerations must be weighed for importers considering a transition to alternative suppliers. For the United States in particular, arms transfers are understood as signaling more general political support for a partner. For countries whose pivot to an alternative supplier might disrupt the broader relationship with the United States, the signal of interest divergence between the importer and Washington and the perceived loss of U.S. support could have serious consequences that extend beyond the particular arms in question.

Additionally, the “if we don’t sell” concept raises questions about another foundational premise in the U.S. security cooperation enterprise, namely that arms transfers are an important source of U.S. influence and leverage among recipient countries. If a country can so easily switch from one arms provider to another, it would seem unnecessary for an importer to make any sacrifices, accept any conditions, or bend to the will of a patron for the sake of preserving an essentially fungible arms relationship. In short, concepts surrounding “if we don’t sell” and arms as a means of influence, both of which are foundational principles in U.S. security cooperation, are in some ways incompatible, but continue to drive arms transfer decisions. Perhaps more importantly, the “if we don’t sell” premise betrays a troubling shallowness in many U.S. security partnerships. If a partner so casually would elect to turn to one of Washington’s strategic competitors for its defense needs or to develop deeper defense ties, that suggests a problematic misalignment of interest and perspectives that raises questions about the strategic value of the relationship in the first place.

In this context, assumptions embodied by the “if we don’t sell” concept risk inflating the likelihood and associated risk of a partner’s transition to an alternative defense supplier. Similarly, the argument offers very little space for the consideration of the potential benefits of disassociating from security relationships with countries that are engaged in abusive behaviors and have only a tenuous alignment of interests with the United States. In so doing, the argument distorts the sense of available policy options and risks incentivizing an ever more liberal approach to arms transfers without sufficient regard for the strategic returns or the consequences for civilian protection, good governance, and international peace.

Human Rights and Civilian Protection

Although international humanitarian law, human rights, and civilian harm mitigation have been featured in past policies, the Biden administration’s directive introduces a new approach for assessing and, in some cases, prohibiting a specific arms transfer on the basis of a stricter human rights standard.

The relevant section states,

[N]o arms transfer will be authorized where the United States assesses that it is more likely than not that the arms to be transferred will be used by the recipient to commit, facilitate the recipients’ commission of, or to aggravate risks that the recipient will commit: genocide; crimes against humanity; grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, including attacks intentionally directed against civilian objects or civilians protected as such; or other serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law, including serious acts of genderbased violence or serious acts of violence against children. This assessment shall include consideration of the available information and relevant circumstances, including the proposed recipient’s current and past actions, credible reports that the recipient committed any of the above violations, and other information related to the overall capacity or intention of the recipient to respect international law.

Compared to the two previously issued policies, this new prohibition makes three important changes. First, the level of certainty required to deny an arms transfer is reduced from “actual knowledge” to a “more likely than not” determination that the arms will be used to commit, facilitate the commission of, or aggravate the risk of international law violations. Second, the scope of negative impacts is expanded from the recipient using the arms transferred to commit violations of international law to include situations in which the arms transferred would facilitate the commission of or aggravate the risk that the recipient will commit violations of international law. Finally, the policy explicitly requires the inclusion of specific types of information in the assessment process.

In order to determine whether an international law violation is more likely than not to occur, the Department of State, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Commerce, or a combination of departments, depending on the authority under which the proposed transfer would occur, will need to develop a more robust and expansive risk assessment regime. To carry out an effective assessment, government officials will need guidance on how to incorporate the new broader considerations into their deliberations, including whether an arms transfer will facilitate or aggravate the risk that the recipient will commit violations. This will require a significantly expanded analysis of the recipient’s security forces. For example, one could easily argue that providing a military unit with arms that would allow it to better control territory could aggravate risks if a separate domestic security force was known to detain and torture individuals because that separate force would have access to more civilians over a larger territory. Therefore, the assessment conducted by the relevant U.S. agency will need to include information and analysis on any risks in the state requesting the arms, not just the specific unit or force that would receive the proposed arms.

In order to determine whether an international law violation is more likely than not to occur, the Department of State, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Commerce, or a combination of departments, depending on the authority under which the proposed transfer would occur, will need to develop a more robust and expansive risk assessment regime. To carry out an effective assessment, government officials will need guidance on how to incorporate the new broader considerations into their deliberations, including whether an arms transfer will facilitate or aggravate the risk that the recipient will commit violations. This will require a significantly expanded analysis of the recipient’s security forces. For example, one could easily argue that providing a military unit with arms that would allow it to better control territory could aggravate risks if a separate domestic security force was known to detain and torture individuals because that separate force would have access to more civilians over a larger territory. Therefore, the assessment conducted by the relevant U.S. agency will need to include information and analysis on any risks in the state requesting the arms, not just the specific unit or force that would receive the proposed arms.

For a potential arms recipient to be judged more likely than not to misuse the weapons, the new policy stipulates that the assessment examine “the proposed recipient’s current and past actions, credible reports that the recipient committed any of the specified violations, and other information related to the overall capacity or intention of the recipient to respect international law.” These categories could be applied in a three-element test covering current and past actions, capacity, and intention. If the recipient state meets any of the elements, one could assess that the threshold is met.

Evidence of relevant past and current actions would include credible reports or allegations that operations were conducted with malice or reckless disregard or gross negligence toward civilians or other protected individuals. Such actions must be systematic or more than one-time events. In addition, the recipient state would be judged on whether it had taken effective steps to bring the responsible offenders to justice. If it had not, then the threshold likely would be met.

In terms of the capacity category, the relevant security force or unit of that force would be judged on whether it had the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability to employ the requested arms in a lawful and effective manner. If it did not have the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability, the threshold likely would be met. Alternatively, if the security force was judged as not having the command and control structure needed to meet its legal obligations under international humanitarian law and human rights law, then the threshold also would likely be met.

In terms of the capacity category, the relevant security force or unit of that force would be judged on whether it had the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability to employ the requested arms in a lawful and effective manner. If it did not have the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability, the threshold likely would be met. Alternatively, if the security force was judged as not having the command and control structure needed to meet its legal obligations under international humanitarian law and human rights law, then the threshold also would likely be met.

The final category concerns intention, specifically judging whether it is the deliberate purpose of the recipient state to employ the arms to commit or facilitate the commission of an act that is a violation of international law as specified in the policy. The review should be that of general intent rather than a specific intent to commit or facilitate commission of a certain action at a specified time. Additionally, the recipient state does not need to have knowledge that a certain action would be a violation of international law as long as there is intention to commit or facilitate the forbidden action, such as targeting civilians or torturing prisoners.

Incomplete Data

In order to conduct this assessment adequately, the relevant U.S. department will need information that, under current practice, is not always collected or made available in a systemic way. For example, the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor annually produces a volume titled “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” which can provide some insight into human rights violations, but frequently does not have the level of detail needed to determine which specific forces commit violations or the causes of such violations.6 As a result, although the report would be helpful to the arms transfer policy analysis, it would not be sufficient.

The Defense Department’s 2022 Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan recognized this deficiency in information and reporting processes. It required the department to develop procedures and a framework to “to assess, monitor, and evaluate the ability, willingness, norms, and practices of allies and partners to implement appropriate civilian harm mitigation and response practices” and to ensure the assessments are used to shape and implement security cooperation programs, many of which include arms transfers. It also called for the formulation of guidance on responding to reports of civilian harm by ally or partner forces from governmental and nongovernmental sources. Nongovernmental organizations and civil society regularly collect and report on information that would be valuable to the type of assessment required by the new arms transfer policy.

All of this information, even if adequately collected by these disparate sources, needs to be readily accessible to the relevant individuals who review and approve arms transfers at each U.S. department that has arms transfer authority. It must be available for review on a regular basis, but not necessarily in every case.

U.S. officials have said they were already frequently if not always applying a higher standard to arms transfer decisions than the previous “actual knowledge” standard. Even if true to some extent, this higher standard is not yet applied through a methodical, standardized process. The National Security Council should provide clear guidance on how to collect the relevant information and apply this standard, even if such guidance varies depending on the mechanism for transfer and the types of arms transferred. Additionally, the results of such analysis should be memorialized in a standard written document and made available for future reference in similar situations, such as tactical training for the same state or transfers to other states with similar risks.

U.S. officials have said they were already frequently if not always applying a higher standard to arms transfer decisions than the previous “actual knowledge” standard. Even if true to some extent, this higher standard is not yet applied through a methodical, standardized process. The National Security Council should provide clear guidance on how to collect the relevant information and apply this standard, even if such guidance varies depending on the mechanism for transfer and the types of arms transferred. Additionally, the results of such analysis should be memorialized in a standard written document and made available for future reference in similar situations, such as tactical training for the same state or transfers to other states with similar risks.

Developing a standardized process for analysis by building out the three-element test and documenting the results in an easy-to-reference written document will set the stage for effective implementation of the new human rights standard. In order to successfully conduct the assessment, proactive steps must be taken to gather information from relevant U.S. agencies, the press, international organizations, and civil society and then ensure the resulting document is readily available to all U.S. officials who have a role in approving or denying arms transfers. Without such an approach, the much-touted human rights focus of the new policy likely will be only messaging with no noticeable difference in actual arms transfers.

The Importance of Implementation

Although the new policy is a step in the right direction of ensuring U.S. foreign policy reflects the country’s values and goals, the actual positive effect or lack thereof should be measured by its implementation. A policy on its own does not guarantee change. A Government Accountability Office report in 2019 compared conventional arms transfer policies from the Trump administration and the Obama administration and found that the two directives did not result in any notable changes to processes for reviewing proposed arms sales.7 If the Biden administration wants its policy to be more than strategic messaging, additional guidance and new processes are needed. Realizing the high-minded aspirations of this new directive will require critical reflections on ill-conceived strategic concepts, as well as more concrete guidance on applying the new human rights standard.

Time will tell if the changes in rhetoric will take root in practice and shape the practicalities of the U.S. arms trade. In particular, it will be important to watch for concrete changes in terms of arms trade decisions, human rights due diligence, and decisions to suspend, curtail, or condition certain arms transfers.

ENDNOTES

1. Pieter D. Wezeman, Justine Gadon, and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2022,” SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2023, p. 2, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2303_at_fact_sheet_2022_v2.pdf.

2. Executive Office of the President, “Memorandum on United States Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, National Security Memorandum/NSM-18,” February 23, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/02/23/memorandum-on-united-states-conventional-arms-transfer-policy/; John Chappell and Ari Tolany, “Unpacking Biden’s Conventional Arms Transfer Policy,” Lawfare, March 2, 2023, https://www.lawfareblog.com/unpacking-bidens-conventional-arms-transfer-policy.

3. Jesus Rodriguez and Matthew Choi, “Trump: Saudi Arabia Would Turn to Russia, China If U.S. Ends Arms Sales Over Missing Journalist,” Politico, October 11, 2018; Zachary Cohen and Betsy Klein, “Trump Vetoes 3 Bills Prohibiting Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia,” CNN, July 24, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/24/politics/saudi-arms-sale-resolutions-trump-veto/index.html.

4. Restraint was also a theme and explicit criterion in the Carter administration’s 1977 conventional arms transfer policy.

5. Elias Yousif, “If We Don’t Sell It, Someone Else Will: Dependence & Influence in US Arms Transfers,” Stimson Center, March 30, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/if-we-dont-sell-it-someone-else-will-dependence-influence-in-us-arms-transfers/.

6. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/reports-bureau-of-democracy-human-rights-and-labor/country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/ (accessed April 19, 2023).

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office to Senator Robert Menendez, “Conventional Arms Transfer Policy: Agency Processes for Reviewing Direct Commercial Sales and Foreign Military Sales Align With Policy Criteria,” GAO-19-673R, September 9, 2019, pp. 7–8, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-673r.pdf.

Rachel Stohl is vice president of research programs at the Stimson Center and director of the Conventional Defense Program. Loren Voss is a nonresident fellow in the program. Elias Yousif is a research analyst in the program.

Nevertheless, nearly all of the world's nine nuclear-armed states continue to improve their nuclear arsenals, including by regularly conducting flight tests of missiles designed to deliver nuclear weapons to maintain existing nuclear weapons capabilities, develop new nuclear weapons systems, or simply demonstrate their capacity to annihilate their adversaries.

Nevertheless, nearly all of the world's nine nuclear-armed states continue to improve their nuclear arsenals, including by regularly conducting flight tests of missiles designed to deliver nuclear weapons to maintain existing nuclear weapons capabilities, develop new nuclear weapons systems, or simply demonstrate their capacity to annihilate their adversaries.

Although many of the tens of thousands of weapons that Washington exports abroad each year flow to like-minded partners with commendable human rights records, many end up in the hands of governments engaged in conflict, accused of civil and human rights abuses, or found to be undermining U.S. interests. Such transfers have long cast a shadow on the U.S. commitment to international human rights and raised questions as to the wisdom and morality of enabling the predatory or destabilizing behaviors of questionable partners.

Although many of the tens of thousands of weapons that Washington exports abroad each year flow to like-minded partners with commendable human rights records, many end up in the hands of governments engaged in conflict, accused of civil and human rights abuses, or found to be undermining U.S. interests. Such transfers have long cast a shadow on the U.S. commitment to international human rights and raised questions as to the wisdom and morality of enabling the predatory or destabilizing behaviors of questionable partners. In order to determine whether an international law violation is more likely than not to occur, the Department of State, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Commerce, or a combination of departments, depending on the authority under which the proposed transfer would occur, will need to develop a more robust and expansive risk assessment regime. To carry out an effective assessment, government officials will need guidance on how to incorporate the new broader considerations into their deliberations, including whether an arms transfer will facilitate or aggravate the risk that the recipient will commit violations. This will require a significantly expanded analysis of the recipient’s security forces. For example, one could easily argue that providing a military unit with arms that would allow it to better control territory could aggravate risks if a separate domestic security force was known to detain and torture individuals because that separate force would have access to more civilians over a larger territory. Therefore, the assessment conducted by the relevant U.S. agency will need to include information and analysis on any risks in the state requesting the arms, not just the specific unit or force that would receive the proposed arms.

In order to determine whether an international law violation is more likely than not to occur, the Department of State, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Commerce, or a combination of departments, depending on the authority under which the proposed transfer would occur, will need to develop a more robust and expansive risk assessment regime. To carry out an effective assessment, government officials will need guidance on how to incorporate the new broader considerations into their deliberations, including whether an arms transfer will facilitate or aggravate the risk that the recipient will commit violations. This will require a significantly expanded analysis of the recipient’s security forces. For example, one could easily argue that providing a military unit with arms that would allow it to better control territory could aggravate risks if a separate domestic security force was known to detain and torture individuals because that separate force would have access to more civilians over a larger territory. Therefore, the assessment conducted by the relevant U.S. agency will need to include information and analysis on any risks in the state requesting the arms, not just the specific unit or force that would receive the proposed arms. In terms of the capacity category, the relevant security force or unit of that force would be judged on whether it had the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability to employ the requested arms in a lawful and effective manner. If it did not have the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability, the threshold likely would be met. Alternatively, if the security force was judged as not having the command and control structure needed to meet its legal obligations under international humanitarian law and human rights law, then the threshold also would likely be met.

In terms of the capacity category, the relevant security force or unit of that force would be judged on whether it had the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability to employ the requested arms in a lawful and effective manner. If it did not have the capacity or had a significantly inconsistent capability, the threshold likely would be met. Alternatively, if the security force was judged as not having the command and control structure needed to meet its legal obligations under international humanitarian law and human rights law, then the threshold also would likely be met. U.S. officials have said they were already frequently if not always applying a higher standard to arms transfer decisions than the previous “actual knowledge” standard. Even if true to some extent, this higher standard is not yet applied through a methodical, standardized process. The National Security Council should provide clear guidance on how to collect the relevant information and apply this standard, even if such guidance varies depending on the mechanism for transfer and the types of arms transferred. Additionally, the results of such analysis should be memorialized in a standard written document and made available for future reference in similar situations, such as tactical training for the same state or transfers to other states with similar risks.

U.S. officials have said they were already frequently if not always applying a higher standard to arms transfer decisions than the previous “actual knowledge” standard. Even if true to some extent, this higher standard is not yet applied through a methodical, standardized process. The National Security Council should provide clear guidance on how to collect the relevant information and apply this standard, even if such guidance varies depending on the mechanism for transfer and the types of arms transferred. Additionally, the results of such analysis should be memorialized in a standard written document and made available for future reference in similar situations, such as tactical training for the same state or transfers to other states with similar risks.

It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about these trends. The global pandemic may have affected the ability of states to submit reports. Developing countries in particular still face difficulties in submitting treaty-required reports. In some cases, only a single official is filing reports to comply with a number of other international and regional arms control regimes besides the ATT, or officials charged with reporting responsibilities lack capabilities. There are also challenges to collecting information from diverse governmental agencies and, in some instances, a lack of political commitment to their obligation to submit reports.

It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about these trends. The global pandemic may have affected the ability of states to submit reports. Developing countries in particular still face difficulties in submitting treaty-required reports. In some cases, only a single official is filing reports to comply with a number of other international and regional arms control regimes besides the ATT, or officials charged with reporting responsibilities lack capabilities. There are also challenges to collecting information from diverse governmental agencies and, in some instances, a lack of political commitment to their obligation to submit reports. Paul Walker: You've recently come from the 102nd CWC Executive Council meeting. It was quite lively and had some interesting statements by a couple dozen of the state-parties. There's also been the open-ended working group, headed by the Estonian ambassador, Lauri Kuusing, who has been active in considering what results we want out of the fifth review conference.

Paul Walker: You've recently come from the 102nd CWC Executive Council meeting. It was quite lively and had some interesting statements by a couple dozen of the state-parties. There's also been the open-ended working group, headed by the Estonian ambassador, Lauri Kuusing, who has been active in considering what results we want out of the fifth review conference. Van der Kwast: We absolutely agree that they should not come primarily from voluntary donations but rather mainly from the central budget. At the same time, that might be difficult. I think the good thing is that we have the ChemTech Center, and it has been paid for completely by donations from different states.… [S]tates have given opportunities for the organization to work it out, and I think that's the right order because then you cannot see a situation whereby states that have donated more would direct the direction of activities of the center. That's a good starting point.

Van der Kwast: We absolutely agree that they should not come primarily from voluntary donations but rather mainly from the central budget. At the same time, that might be difficult. I think the good thing is that we have the ChemTech Center, and it has been paid for completely by donations from different states.… [S]tates have given opportunities for the organization to work it out, and I think that's the right order because then you cannot see a situation whereby states that have donated more would direct the direction of activities of the center. That's a good starting point. “The United States has been doing this for decades,” Putin argued on March 26, referring to the NATO nuclear sharing arrangement in which six European bases across five NATO countries host about 100 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons.

“The United States has been doing this for decades,” Putin argued on March 26, referring to the NATO nuclear sharing arrangement in which six European bases across five NATO countries host about 100 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons. The Sentinel program “may miss its goal of initial deployment in May 2029 by as much as two years, according to information presented at a high-level Pentagon review last month,” Bloomberg first reported on March 23.

The Sentinel program “may miss its goal of initial deployment in May 2029 by as much as two years, according to information presented at a high-level Pentagon review last month,” Bloomberg first reported on March 23. Meanwhile, the Defense Department’s other nuclear modernization programs continue apace. The Air Force requested $5.3 billion for R&D and construction of the B-21 Raider dual-capable strategic bomber, an increase from the fiscal year 2023 authorization of $4.9 billion. The Pentagon unveiled the bomber in December, and it will have its first flight test later this year. The Air Force plans to purchase at least 100 bombers.

Meanwhile, the Defense Department’s other nuclear modernization programs continue apace. The Air Force requested $5.3 billion for R&D and construction of the B-21 Raider dual-capable strategic bomber, an increase from the fiscal year 2023 authorization of $4.9 billion. The Pentagon unveiled the bomber in December, and it will have its first flight test later this year. The Air Force plans to purchase at least 100 bombers. “The Air Force does not currently intend to pursue follow-on procurement of ARRW [the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon] once the prototyping program concludes,” Andrew Hunter, assistant secretary of defense for acquisition, told a congressional hearing on March 29.

“The Air Force does not currently intend to pursue follow-on procurement of ARRW [the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon] once the prototyping program concludes,” Andrew Hunter, assistant secretary of defense for acquisition, told a congressional hearing on March 29. U.S. President Joseph Biden and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol agreed to create the U.S-South Korean Nuclear Consultative Group during Yoon’s visit to Washington on April 26. According to a declaration issued by the two leaders, the group will “discuss nuclear and strategic planning” and manage the North Korean nuclear threat.

U.S. President Joseph Biden and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol agreed to create the U.S-South Korean Nuclear Consultative Group during Yoon’s visit to Washington on April 26. According to a declaration issued by the two leaders, the group will “discuss nuclear and strategic planning” and manage the North Korean nuclear threat. The deployment comes earlier than expected. Previous U.S. reports estimated that China would deploy the JL-3 missile along with the country’s next-generation ballistic missile submarine, the Type 096, which is believed to be still under construction. (See

The deployment comes earlier than expected. Previous U.S. reports estimated that China would deploy the JL-3 missile along with the country’s next-generation ballistic missile submarine, the Type 096, which is believed to be still under construction. (See  After Iran in June 2022 removed surveillance cameras from certain facilities and the monitor that tracked uranium enrichment at its Natanz plant in real time, Grossi has raised concerns about the gap in IAEA monitoring of Iran’s nuclear program. He warned that the reduction in transparency would pose challenges for establishing baseline inventories in certain areas of the program, such as centrifuge component production. (See

After Iran in June 2022 removed surveillance cameras from certain facilities and the monitor that tracked uranium enrichment at its Natanz plant in real time, Grossi has raised concerns about the gap in IAEA monitoring of Iran’s nuclear program. He warned that the reduction in transparency would pose challenges for establishing baseline inventories in certain areas of the program, such as centrifuge component production. (See