November 2021

By Noah C. Mayhew

An era of remarkable cooperation between two Cold War adversaries started in 1988 with a controlled detonation of a nuclear device at the Nevada Test Site. Teams of U.S. and Soviet scientists looked on, hoping that the heavy instrumentation they had jointly designed would accurately measure the yield of the explosion in support of verification of the 1974 Threshold Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.1 The exercise, known as the Joint Verification Experiment, was a success. It was also the first concrete manifestation of official laboratory-to-laboratory cooperation on nuclear treaty verification between the two nuclear superpowers.

This exercise and an analogous test at the Semipalatinsk site in Kazakhstan four weeks later would open the door to decades of intensive collaboration between U.S. and Soviet scientists, and later Russian scientists, on reducing the legacy nuclear dangers born of the Cold War. During this unprecedented period of cooperation, lab-to-lab projects became a constructive tool in the bilateral diplomatic tool belt. They transformed the old adage “trust but verify” into “trust and benefit” and provided a parallel track for advancing mutual security alongside traditional governmental diplomatic channels.

This exercise and an analogous test at the Semipalatinsk site in Kazakhstan four weeks later would open the door to decades of intensive collaboration between U.S. and Soviet scientists, and later Russian scientists, on reducing the legacy nuclear dangers born of the Cold War. During this unprecedented period of cooperation, lab-to-lab projects became a constructive tool in the bilateral diplomatic tool belt. They transformed the old adage “trust but verify” into “trust and benefit” and provided a parallel track for advancing mutual security alongside traditional governmental diplomatic channels.

Due to the serious downturn in U.S.-Russian relations in the last decade, however, lab-to-lab cooperation has all but disappeared. A crushing blow came in 2016 when Russia, under the pressure of intensifying U.S. sanctions, suspended a 2013 agreement on scientific cooperation that built on the landmark 1992 Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program.2

That history is relevant now as the United States and Russia pursue strategic stability talks at a moment of intense animosity and distrust. The summit between U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin in June opened a window to begin to stabilize the bilateral relationship; reviving lab-to-lab cooperation could be a relatively easy first step on that difficult path.

The two leaders articulated a clear-eyed vision of their national priorities and met without any pretense that the summit would be, as Biden put it, a “kumbaya moment.” The outcome was modest: an agreement to launch a series of talks on strategic stability that will be “deliberate and robust” and will seek to “lay the groundwork for future arms control and risk reduction measures.”3

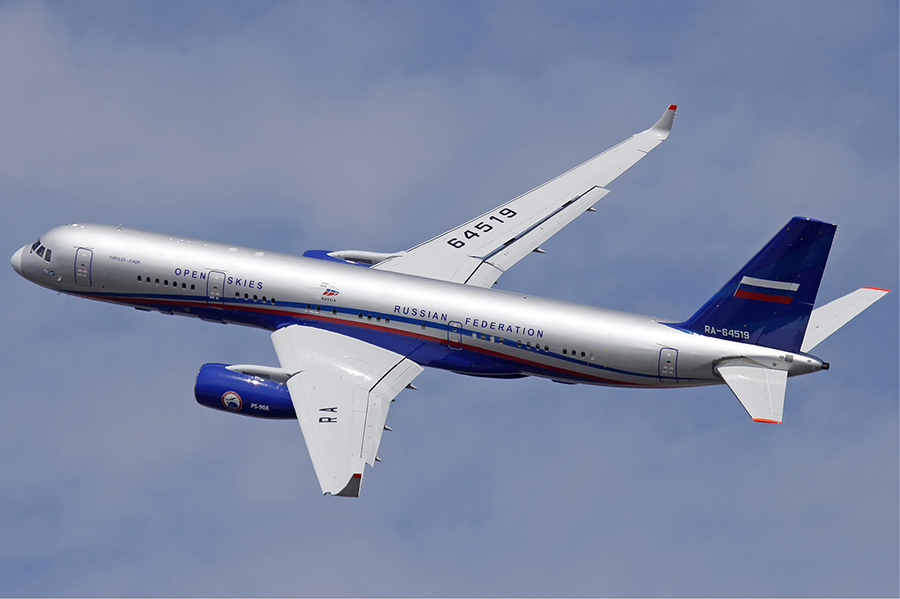

With no treaty yet lined up to replace the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and two other treaties—the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty, which were undermined by the withdrawal of Washington and Moscow—U.S.-Russian relations are at a crossroads, and success at these talks is sorely needed. If the dialogue, which started in July and September, devolves into toxic accusations, bilateral relations would become even more hostile and could result in New START expiring in 2026 with nothing to replace it.

On the other hand, productive talks could advance relative stability and predictability in the U.S.-Russian security domain by facilitating new treaties, a reduction in deployed and maybe nondeployed nuclear weapons, and perhaps further cuts in fissile material stockpiles. Without a doubt, any agreement with a realistic chance of entering into force requires verification and a mechanism to resolve disputes. These components are no panacea—they did not save the INF Treaty, for example—but without them, no agreement is possible at all.

As the two sides move to discuss verification, they need to consider the rich history in which the U.S. and Russian national laboratories worked together on technical solutions to one of the core challenges of any arms control agreement: verifying that both sides are adhering to their commitments. Reviving and expanding formal lab-to-lab cooperation and technical cooperation between the national academies of sciences would be an easy way for the White House and the Kremlin to test their commitments to ensuring that strategic stability talks make progress.

The Urgency

Success will depend heavily on the confluence of political will and technical verification capability. As political will can be fleeting, cooperation at the technical level needs to be put in place to support the critical verification aspects of a potential agreement. Commencing formal lab-to-lab cooperation on nuclear verification now will make it more likely that a potential agreement can be operationalized immediately.

Past arms control agreements, including New START, have been verified through on-site inspections, notifications on the movements and status of nuclear armaments subject to the agreement, and data exchanges, including on telemetry information related to intercontinental ballistic missile and submarine-launched ballistic missile launches. Today, the nuclear arms control community is facing new challenges in verification, and emerging technologies could help address them.

For instance, it may be desirable to use remote sensing or monitoring technology, paired with jointly trained machine-learning algorithms to augment the work done by inspectors. This could increase confidence in implementing an agreement at a time when trust is virtually nonexistent. Given the U.S. intelligence community reports of rising Russian cyberattacks against the United States, joint development of such a tool could be a useful way to shield a future agreement from accusations of cheating or more efficiently deal with them should they arise.

If lab-to-lab cooperation is not prioritized early, it may lead to a situation where political will to conclude an agreement will not be matched by the technical capability to verify it. As demonstrated by the demise of the Trilateral Initiative, which was envisioned by the United States, Russia, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to remove excess fissile material from weapons programs and place it under IAEA safeguards without exposing proliferation-sensitive information, the technical capability often takes longer to develop and authenticate than the political will lasts.4

The initiative was active from 1996 until 2002. Although U.S. and Russian scientists continued to jointly develop the technical aspects of verification after the project ended, they did not demonstrate a prototype that would satisfy U.S. and Russian security officials until 2010, long after the political will to implement the initiative had dissipated.5

The Benefit

Lab-to-lab and other technical cooperation, such as through the national academies of science, do not just help avoid pitfalls in treaty verification. Research into new and emerging technologies could be used to strengthen a verification regime, perhaps by identifying options to verify provisions that once were considered unverifiable. Verification is about the balance between transparency and secrecy. Each side must disclose enough information to ensure effective verification but not more than is absolutely needed. New technologies can expand options available to negotiators as they search for that balance.

As they are developed and authenticated, new approaches could include machine learning to better analyze large data sets and enhanced use of satellite imagery. Utilizing these technologies would not come without challenges. Machine-learning algorithms require extensive development before deployment, and their application would likely be limited to open-source data. They would not replace on-site inspections as both sides would surely wish to keep their own “boots on the ground,” but they may provide an extra layer of confidence that both sides are adhering to an agreement. They could also enable a jointly managed technical basis for addressing potential discrepancies or suspicious activities should they arise.

Similarly, satellite imagery is already used as national technical means, but the quality is much higher than in the past and can now provide more data. If used for treaty verification, however, more work will need to be done to ensure mutual access to data from satellite imagery and to assure both countries that no one has tampered with the data.

Another possibility for cooperation is distributed ledger technology (DLT), commonly known as blockchain, which is used to establish a digital, cryptographically verified, tamper-evident, shared ledger that could record data related to arms control verification activities.6 DLT could be used to share data in a more secure way, inspiring confidence that data exchange logs are genuine and have not been altered while avoiding complete disclosure of sensitive data. The tamper-evident feature of the technology is particularly salient, considering the allegations of Russian cyberattacks.

These and other tools are already being researched for application in IAEA safeguards, but could also have applications in arms control verification if the parties to an agreement can authenticate them for use. Emerging technologies cannot replace any existing part of arms control verification, such as on-site inspections or radiation measurements, but they could augment existing capabilities and increase confidence that all parties to an agreement are in compliance.

Revitalized scientific cooperation would also be beneficial in advancing existing techniques, such as radiation measurements using neutron multiplicity counting and high-resolution gamma spectrometry. They have been used for verifying fissile material, including warheads, for decades.7 Could these techniques be used more effectively? Might they be reconfigured to suit new verification challenges? U.S. and Russian scientists have worked together in this domain before and could do so again.

Revitalized scientific cooperation would also be beneficial in advancing existing techniques, such as radiation measurements using neutron multiplicity counting and high-resolution gamma spectrometry. They have been used for verifying fissile material, including warheads, for decades.7 Could these techniques be used more effectively? Might they be reconfigured to suit new verification challenges? U.S. and Russian scientists have worked together in this domain before and could do so again.

In this regard, scientific cooperation serves not just as a supporting mechanism for treaty negotiations, but also as a mechanism to lay the groundwork for future cooperative endeavors. Over the years, the experience of implementing joint projects provided the United States and Russia a view into each other’s nuclear thinking. They cooperated not just on nuclear safety, security, and other defense-related fields, but also on the fundamental sciences. It proved that cooperation did not threaten national security, but rather strengthened it.

The Challenge

Lab-to-lab cooperation is not an arms control panacea, nor is it as simple as flipping a switch for it to resume. Although immensely beneficial to the United States and Russia in the 1990s and 2000s, such collaboration is very sensitive and requires a level of trust that is now absent in the U.S.-Russian relationship. That is why one of the first tasks of the strategic stability talks must be establishing a minimum level of confidence that would allow scientific cooperation to proceed.

History has proved that such cooperation is possible, and the field of nuclear arms control would be well served to capitalize on the experience of those who have already participated in these activities.

The bilateral relationship is at a critical juncture. If the talks go well, a period of more stable relations could ensue, even as certain tensions persist. If talks do not go well, the already poisonous state of U.S.-Russian relations could worsen.

Both governments must invest now in new confidence- and transparency-building measures to keep their delicate relationship from breaking. As with the nuclear age itself, that starts with cooperation among the scientists and engineers who command the technical nuclear expertise.

ENDNOTES

1. See Siegfried S. Hecker, ed., Doomed to Cooperate: How American and Russian Scientists Joined Forces to Avert Some of the Greatest Post-Cold War Nuclear Dangers (Los Alamos, NM: Bathtub Row Press, 2016).

2. Government of the Russian Federation, “Suspending the Russian-U.S. Agreement on Cooperation in Nuclear- and Energy-Related Scientific Research and Development,” October 5, 2016, http://government.ru/en/docs/24766/.

3. The White House, “U.S.-Russia Presidential Joint Statement on Strategic Stability,” June 16, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/16/u-s-russia-presidential-joint-statement-on-strategic-stability/.

4. Thomas E. Shea and Laura Rockwood, “IAEA Verification of Fissile Material in Support of Nuclear Disarmament,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, May 2015, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/iaeaverification.pdf.

5. Sergey Kondratov et al., “Testing the AVNG,” Los Alamos National Laboratory, LA-UR-10-02626, July 11, 2010.

6. Cindy Vestergaard and Maria Lovely Umayam, “Complementing the Padlock: The Prospect of Blockchain for Strengthening Nuclear Security,” Stimson Center, June 2020, https://www.stimson.org/2020/complementing-the-padlock-the-prospect-of-blockchain-for-strengthening-nuclear-security/.

7. Edward M. Ifft, “Verifying Nuclear Arms Control and Disarmament,” in Verification Yearbook 2001, n.d., https://www.vertic.org/media/Archived_Publications/Yearbooks/2001/VY01_Ifft.pdf.

Noah C. Mayhew is a research associate at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation focusing on nuclear non-proliferation, safeguards and verification, arms control, and U.S.–Russian relations. He is a commissioner on the trilateral Young Deep Cuts Commission and the co-chair of the Emerging Voices Network’s nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty Working Group.

On Dec. 15, Karen Donfried, the U.S. assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, met Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, who transmitted two draft agreements outlining political and military security guarantees Moscow wants from the United States and NATO. They include demands that NATO renounce any expansion eastward into states of the former Soviet bloc, including Ukraine, and limit troop and weapons deployments and military drills on NATO’s eastern flank.

On Dec. 15, Karen Donfried, the U.S. assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, met Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, who transmitted two draft agreements outlining political and military security guarantees Moscow wants from the United States and NATO. They include demands that NATO renounce any expansion eastward into states of the former Soviet bloc, including Ukraine, and limit troop and weapons deployments and military drills on NATO’s eastern flank. “Responsibility for the deterioration of the Open Skies regime lies fully with the United States as the country that started the destruction of the treaty,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a Dec. 18 statement.

“Responsibility for the deterioration of the Open Skies regime lies fully with the United States as the country that started the destruction of the treaty,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a Dec. 18 statement. This exercise and an analogous test at the Semipalatinsk site in Kazakhstan four weeks later would open the door to decades of intensive collaboration between U.S. and Soviet scientists, and later Russian scientists, on reducing the legacy nuclear dangers born of the Cold War. During this unprecedented period of cooperation, lab-to-lab projects became a constructive tool in the bilateral diplomatic tool belt. They transformed the old adage “trust but verify” into “trust and benefit” and provided a parallel track for advancing mutual security alongside traditional governmental diplomatic channels.

This exercise and an analogous test at the Semipalatinsk site in Kazakhstan four weeks later would open the door to decades of intensive collaboration between U.S. and Soviet scientists, and later Russian scientists, on reducing the legacy nuclear dangers born of the Cold War. During this unprecedented period of cooperation, lab-to-lab projects became a constructive tool in the bilateral diplomatic tool belt. They transformed the old adage “trust but verify” into “trust and benefit” and provided a parallel track for advancing mutual security alongside traditional governmental diplomatic channels. Revitalized scientific cooperation would also be beneficial in advancing existing techniques, such as radiation measurements using neutron multiplicity counting and high-resolution gamma spectrometry. They have been used for verifying fissile material, including warheads, for decades.

Revitalized scientific cooperation would also be beneficial in advancing existing techniques, such as radiation measurements using neutron multiplicity counting and high-resolution gamma spectrometry. They have been used for verifying fissile material, including warheads, for decades. The two countries released a joint statement following the Sept. 30 meeting in Geneva, which described the dialogue as “intensive and substantive” and officially named the Working Group on Principles and Objectives for Future Arms Control and the Working Group on Capabilities and Actions With Strategic Effects.

The two countries released a joint statement following the Sept. 30 meeting in Geneva, which described the dialogue as “intensive and substantive” and officially named the Working Group on Principles and Objectives for Future Arms Control and the Working Group on Capabilities and Actions With Strategic Effects. U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to relaunch a bilateral strategic stability dialogue during their June summit, and delegations representing Washington and Moscow held their first meeting in Geneva on July 28. (See

U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to relaunch a bilateral strategic stability dialogue during their June summit, and delegations representing Washington and Moscow held their first meeting in Geneva on July 28. (See  The U.S. delegation was led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Bonnie Jenkins, the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security. The U.S. team included officials from the National Security Council and the Defense, Energy, and State departments. Ryabkov led the Russian delegation.

The U.S. delegation was led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Bonnie Jenkins, the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security. The U.S. team included officials from the National Security Council and the Defense, Energy, and State departments. Ryabkov led the Russian delegation. Just as importantly, the two men also reaffirmed the commonsense principle, agreed on by U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev

Just as importantly, the two men also reaffirmed the commonsense principle, agreed on by U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev  The announcement marked the first step in what could be a long, contentious process to make progress on nuclear arms control after more than a decade of deadlock and before the last remaining arms control agreement expires in five years between the world’s two largest nuclear powers.

The announcement marked the first step in what could be a long, contentious process to make progress on nuclear arms control after more than a decade of deadlock and before the last remaining arms control agreement expires in five years between the world’s two largest nuclear powers.