Volume 13, Issue 3, May 18, 2021

With the Biden administration set to release its fiscal year 2022 budget request May 27 and conduct a more comprehensive review of nuclear policy later this year, the debate about how the United States should approach nuclear modernization has reached a fever pitch.

The nation is planning to spend at least $1.5 trillion over the next several decades to maintain and upgrade nearly its entire nuclear arsenal. This explosion of spending comes at a time when a devastating global pandemic has redefined how many Americans think about security, China’s growing role on the global stage poses multifaceted challenges, and most experts believe that the U.S. defense budget will remain flat over the next several years.

While the Trump administration expanded the role of and spending on the arsenal and turned its back on arms control as a national security tool, the Biden administration in its interim national security strategic guidance released in March said that it “will take steps to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, while ensuring our strategic deterrent remains safe, secure, and effective and that our extended deterrence commitments to our allies remain strong and credible.”

The Biden administration smartly and quickly agreed with Russia to a five-year extension of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) without conditions and pledged to “pursue new arms control arrangements.”

But there is more work to do. Current U.S. nuclear weapons policies exceed what is necessary to deter a nuclear attack from any U.S. adversary, and the financial and opportunity costs of the current nuclear modernization plan are rising fast.

The Biden administration’s topline discretionary budget request released in April said that “While the Administration is reviewing the U.S. nuclear posture, the discretionary request supports ongoing nuclear modernization programs while ensuring that these efforts are sustainable.” But there are several modernization efforts that do not meet the “sustainable” criterion.

The administration can and should move the United States toward a nuclear strategy that will continue to ensure an effective nuclear deterrent, reflects a narrower role for nuclear weapons, raises the nuclear threshold, is more affordable, and supports the pursuit of additional arms control and reduction measures designed to enhance stability and reduce the chance of nuclear conflict.

Below are responses to several common arguments advanced by the supporters of the nuclear weapons status quo against proposals for adjusting the current U.S. nuclear modernization plan so that it is less costly and more conducive to efforts to reduce nuclear weapons risks.

Claim: Nuclear weapons don’t actually cost that much.

Response: The reality is that the financial cost to sustain and upgrade the U.S. nuclear arsenal is growing increasingly punishing. President Trump’s fiscal year (FY) 2021 budget request of $44.5 billion for nuclear weapons was a 19 percent increase over the previous year.

Though the sunk costs to date have been relatively minimal, spending on nuclear weapons is slated to increase dramatically in the coming years. In contrast, the topline national defense budget will likely be flat at best. (The Biden administration’s FY 2022 defense topline request does not keep pace with inflation.) Nearly the entire arsenal is slated for an upgrade and/or replacement at roughly the same time, and the bulk of the modernization portion of the cost will occur over the next 10 to 15 years.

Though the sunk costs to date have been relatively minimal, spending on nuclear weapons is slated to increase dramatically in the coming years. In contrast, the topline national defense budget will likely be flat at best. (The Biden administration’s FY 2022 defense topline request does not keep pace with inflation.) Nearly the entire arsenal is slated for an upgrade and/or replacement at roughly the same time, and the bulk of the modernization portion of the cost will occur over the next 10 to 15 years.

One oft-heard claim in support of the status quo is that even at its peak in the late-2020s, spending on nuclear weapons is affordable because it will only consume roughly 6.4 percent of total Pentagon spending. But this figure is misleading for several reasons. The estimate, which was prepared to inform the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, is now nearly 4 years old. The projection also does not include spending on nuclear warheads and their supporting infrastructure at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a semiautonomous Energy Department agency whose nuclear weapons activities are part of the national defense budget. Since the end of the Obama administration, NNSA weapons activities spending has grown by roughly 70 percent. When NNSA spending is included, nuclear weapons already accounted for 6 percent of the total FY 2021 national defense budget request.

Program cost overruns and likely schedule delays are poised to exacerbate the financial challenge. Last year, the NNSA requested an unplanned increase of $2.8 billion relative to earlier planning. The agency’s 25-year plan published in December showed that projected spending on nuclear weapons activities has risen to $505 billion. That is a staggering increase of $113 billion from the 2020 version of the plan.

The scope and schedule goals for the nuclear modernization effort are highly aggressive and face major execution problems. As the Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted in a report published in May, “every nuclear triad replacement program—including the B21, LRSO, GBSD, and Columbia class submarine, and every ongoing bomb and warhead modernization program—faces the prospect of delays due to program-specific and” Defense and Energy Department “wide risk factors.” Extending the schedule for these programs will increase their cost.

The growing price tag of the nuclear mission is coinciding with Pentagon plans to recapitalize large portions of the nation’s conventional force. The last time the United States simultaneously modernized its conventional and nuclear forces in the 1980s, it did so alongside an increasing defense budget, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work recently noted. “With such increases, the Pentagon did not have to trade conventional capability for nuclear forces,” Work points out, but “unless something changes, that will not be the case this time.”

The growing price tag of the nuclear mission is coinciding with Pentagon plans to recapitalize large portions of the nation’s conventional force. The last time the United States simultaneously modernized its conventional and nuclear forces in the 1980s, it did so alongside an increasing defense budget, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work recently noted. “With such increases, the Pentagon did not have to trade conventional capability for nuclear forces,” Work points out, but “unless something changes, that will not be the case this time.”

Indeed, in order accommodate the multi-billion dollar unplanned budget increase in FY 2021 for the NNSA, the Navy was forced to cut a second Virginia-class attack submarine from its budget submission. Congress ultimately added the second Virginia back to the budget, but the episode illustrates the significant threat that spending nuclear weapons spending poses to other national security and military priorities.

As the cost of nuclear weapons continues to rise, the choices that are made about what not to fund to pay for them are going to get more difficult, especially amid a flat defense budget. And the longer the government waits to make those hard choices, the more suboptimal they are going to get.

Claim: Adjusting U.S. nuclear force structure and modernization plans in the face of growing Russian and Chinese nuclear threats would be unwise.

Response: The Biden administration is undoubtedly inheriting a less hospitable security environment than what existed when President Obama left office in 2016. On the nuclear front, Russia and China are modernizing their arsenals, developing new weapon capabilities, and, according to U.S. intelligence estimates, projected to increase the size of their nuclear warhead stockpiles over the next decade.

But this does not mean the United States should follow suit – or maintain a nuclear arsenal in excess to what is needed for deterrence.

China’s much smaller nuclear arsenal has grown only modestly over the past decade. While the Defense Department projects that China may at least double its arsenal over the next decade, it estimates Beijing’s current arsenal to be in the low-200s. Should China’s nuclear stockpile double, it would still be many times smaller than the current U.S. stockpile of about 3,800 warheads. Relative to the many challenges China poses to the United States and its allies, the Chinese nuclear challenge is not among the most pressing.

With respect to Russia, in 2013, the Obama administration determined the security of the United States and its allies could be maintained while pursuing up to a one-third reduction in deployed nuclear weapons below the level of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 700 deployed delivery systems as stipulated by New START.

The case for a one-third reduction in deployed strategic forces remains strong. The size of the Russian strategic nuclear force has not changed since then and remains lower than that of the United States. What nefarious opportunities would Moscow be able to exploit in the face of a U.S. nuclear arsenal by 2030 consisting of, for example: 1,000-1,100 deployed warheads on 10 ballistic missile submarines, 300 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and at least 60 long-range bombers; two low-yield warhead delivery options; and 1,500-2,000 warheads in reserve?

The Biden administration should seek to make further reductions in the U.S. arsenal in concert with Russia, as well as bring China off the arms control sidelines. But it should not give Moscow or Beijing veto power over U.S. force adjustments as further reductions will not compromise U.S. national security. Decisions about force needs must take into account the long-term funding challenges posed by maintaining the U.S. arsenal at its current size and consider the opportunity costs.

After all, planned U.S. spending on nuclear weapons poses a major threat to security priorities more relevant to countering Moscow and Beijing and assuring allies, such as pandemic defense and response as well as pacing China’s advancing conventional military capabilities.

As Adm. Philip Davidson, the former head of Indo-Pacific Command, put it earlier this year: “The greatest danger to the future of the United States continues to be an erosion of conventional deterrence.” How does cutting attack submarines to pay for cost overruns at the NNSA address this greatest danger? How does replacing conventional sea-launched cruise missiles on attack submarines with a planned fleet of new nuclear cruise missiles address this greatest danger?

Claim: Adjusting U.S. nuclear modernization plans won’t save money.

Response: Supporters of the current modernization approach claim that the only choice is to proceed full steam ahead with the status quo or allow the U.S. nuclear arsenal to rust into obsolescence. This is a false choice. Adjusting long-standing and more recently adopted nuclear planning assumptions would enable changes to the current nuclear modernization effort and could produce scores of billions of dollars in savings to redirect to higher priority national security needs.

Of course, pressure on the defense budget cannot be relieved solely by reducing nuclear weapons spending, as a significant portion of the overall cost of nuclear weapons remains fixed. That said, changes to the nuclear replacement program could make it easier to execute and ease some of the hard choices facing the overall defense enterprise.

For example, reshaping the spending plans consistent with an up to one-third reduction in deployed nuclear warheads could save at least $80 billion through 2030 while still allowing the United States to maintain a nuclear triad. Such an amount would, for example, be more than enough to fulfill Indo-Pacific Command’s request earlier this year for $22.7 billion to augment the U.S. conventional defense posture in the region through fiscal year 2027 via the Pacific Deterrence Initiative.

Claim: The Minuteman III missile system can’t be life extended again.

Response: ICBMs are the least valuable, least essential, and least stabilizing leg of the nuclear triad. What the nation invests to sustain ICBMs should reflect this reality. Spending approximately $100 billion to buy a new ICBM system over the next 10-15 years and billions more on an upgraded ICBM warhead and the production of plutonium pits for the warhead fails to reflect the limited utility of ICBMs.

The United States currently deploys 400 ICBMs across five states. Supporters argue that the ICBM force presents an attacker with hundreds of targets on the U.S. homeland and is a hedge against a potential future vulnerability in the sea-based leg of the triad. However, even if one supports these arguments, there are cheaper options than going forward with the ICBM replacement program, called the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program.

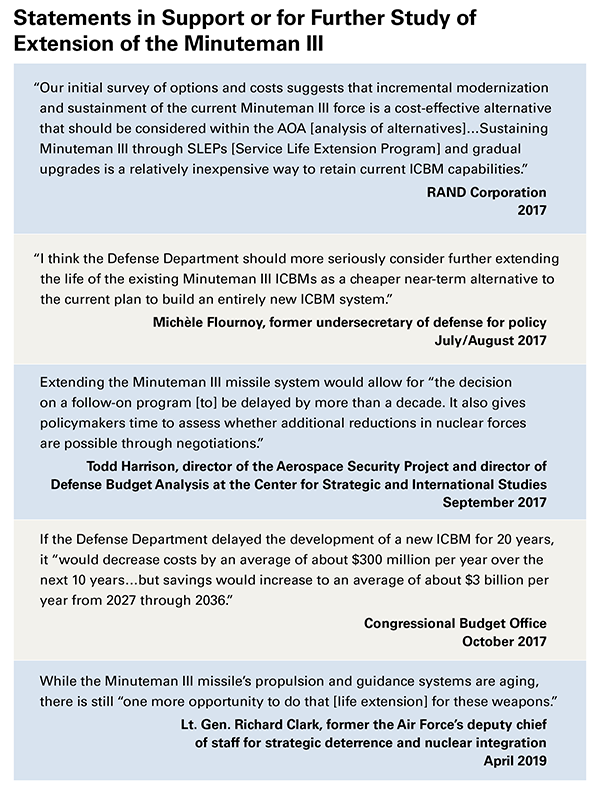

Past independent assessments indicate that it is possible to extend the life of the existing Minuteman III missiles beyond their planned retirement in the 2030 timeframe, as the Defense Department has done before, by refurbishing the rocket motors and other parts.

Past independent assessments indicate that it is possible to extend the life of the existing Minuteman III missiles beyond their planned retirement in the 2030 timeframe, as the Defense Department has done before, by refurbishing the rocket motors and other parts.

In 2017, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that deferring the new missile portion of GBSD by two decades, extending the life of the Minuteman III missiles, and proceeding with refurbishment of the system’s command and control infrastructure as planned could save $37 billion (in 2017 dollars) through the late 2030s. The option value of this approach would be significant as the Pentagon seeks to navigate the daunting conventional and nuclear modernization bow wave that is now upon it.

Defense officials have put forward several arguments against extending the Minuteman III based on the program analysis of alternatives conducted in 2014, but all of the arguments merit greater scrutiny.

The Defense Department claims that the price to build and operate a new missile system would be less than the cost to maintain the Minuteman III. But it seems the Pentagon arrived at this conclusion by comparing the total life-cycle cost of the two options through 2075. Since Minuteman III missiles cannot be extended for the full period, the department assumed a new missile eventually would be needed. Might comparing the two options over a shorter period produce a different answer? The CBO’s analysis suggested the answer is yes.

The Pentagon also argues that a new missile is essential to maintain the current force of 400 deployed ICBMs. While true that there eventually will not be enough Minuteman III motors to maintain a force of 400 ICBMs at the current rate of testing, this problem can be solved by reducing the number of deployed missiles to, say, 300. How did 400 deployed ICBMs through 2075 become a sacrosanct requirement for a modernization decision covering half a century? Furthermore, future arms control agreements could result in the need for fewer ICBMs in the U.S. arsenal, and presidents can also change military requirements to call for fewer ICBMs.

In addition, defense officials say that the ICBM leg of the triad requires new capabilities that the Minuteman III cannot provide, such as additional target coverage and the ability to penetrate advancing adversary missile defenses. These are curious claims.

First, what and how many targets are Minuteman III missiles unable to hit? Targets in China or North Korea that would require overflying Russia? Can these targets not be hit by other U.S. nuclear capabilities, notably the best mobile intercontinental-range missile on the planet: the Trident II D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile?

Regarding the missile defense concern, is this a 2030 problem or a 2075 problem? Are the Russians and Chinese on the verge of unlocking the secret to intercepting scores of hypersonic ICBMs armed with decoys and countermeasures – a secret the United States has been unable to unlock? When the Russians express similar concerns about unconstrained U.S. missile defenses posing a threat to the credibility of their nuclear deterrent, U.S. officials dismiss their concerns as paranoia.

These are questions that need far more compelling answers before proceeding full steam ahead with GBSD. There is no evidence the Pentagon has studied the extension option across a wider range of parameters than those considered in 2014. Adm. Charles Richard, the head of U.S. Strategic Command, conceded in April that the Pentagon “may be able to chart,” a life extension of the Minuteman III, “but there is an enormous amount of detail that has to go into that.” The Pentagon appears to have no choice but to consider alternatives. According to the GAO, GBSD “program schedule delays are likely.”

Might continuing to rely on the Minuteman III system beyond the 2030s entail some technical risk? Yes. Would it be preferable to replace the aging Minuteman III supporting infrastructure, which in many cases relies on parts that are no longer made, in one fell swoop rather than via incremental upgrades? Probably. Would a common configuration for all launch facilities, which GBSD would provide, make maintenance easier? Yes. Would new missiles built to accommodate future technology upgrades be easier to maintain in the long run? Yes.

But while building a new ICBM system might be preferable, it is not essential. Not given the limited utility of ICBMs. Not given the enormous cost of the GBSD program. Not given the availability of the extension and the incremental upgrade option. Not given other pressing priorities amid a flat defense budget. And not given that future arms control agreements could reduce U.S. nuclear forces.

Claim: Adjusting U.S. nuclear modernization plans would undermine the assurance of allies amid allied concern about the threats posed by Russia and China and the strength of the credibility of the U.S. commitment to their security.

Response: The Trump administration attempted to buttress extended deterrence with new nuclear capabilities and more ambiguous language about when it might consider the use of nuclear weapons. These changes do not appear to have assured allies, which suggests that the assurance challenge is more of a political “software” than a military “hardware” problem. Moreover, the most proximate threat Russia and China pose to allies comes from non-nuclear and asymmetric “grey-zone” capabilities that are harder to deter and more likely to lead to conflict escalation. Improving conventional deterrence and alliance cohesion would be more appropriate for this problem than greater reliance on nuclear weapons.

The United States can continue to assure its allies and partners as it reduces the role of nuclear weapons in its strategy, maintains second-to-none conventional military forces, and, most importantly, strengthens political relationships through reaffirmations of the value of alliances, stronger economic and cultural ties, and stepped-up dialogue that tie the United States more closely to the security of its allies.

As former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy Elaine Bunn recently put it:

“The precise make up...of the nuclear force [is] not likely to have the greatest impact on allies’ views of extended nuclear deterrence. That's about the overall relationship, the peacetime consultations, the crisis management exercises. It’s about that whole web of interactions that we have with allies. And so as long as there’s a baseline of an effective nuclear arsenal, I think if we are confident in our nuclear deterrence capabilities then with right consultation allies will be too.”

Claim: Adjusting U.S. nuclear modernization plans would reduce U.S. leverage to achieve new arms control agreements.

Response: First, a close examination of the history of U.S.-Russian arms control raises doubts about the strength of the link between increased U.S. spending on nuclear weapons and arms control success. For example, the U.S. and NATO decision to field new ground-launched nuclear missiles in Europe in the early 1980s is often cited as being essential to convincing Moscow to agree to the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty prohibiting such weapons. But the actual fielding of the new weapons beginning in 1983 prompted Moscow to walk out of arms control talks. The talks did not resume until 1985 following the major political change in the Soviet Union that accompanied Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascension to leader.

Second, even if the modernization program were an effective bargaining chip, the chip can’t be cashed in anytime soon. The program won’t produce an appreciable number of new delivery systems until the late 2020s at the earliest. Third, the Trump administration’s repeated threats to build up the U.S. nuclear arsenal did not force the current Russian and Chinese leadership to capitulate to maximalist U.S. demands for a new arms control agreement.

Fourth, an up to one-third reduction in deployed strategic forces would still leave the United States with ample nuclear capability with which to trade as part of new arms control arrangements with Russia (or in the future China). Even after such a reduction, the United States would retain rough parity with Russia in the number of strategic delivery systems and warheads. Moreover, while past strategic nuclear arms control agreements have included equal ceilings on strategic forces, some agreements have included ranges for the ceilings.

Fifth, Moscow has identified constraints on U.S. non-nuclear weapons, such as missile defense and advanced conventional strike capabilities, as priority conditions for further Russian nuclear cuts, especially cuts to Russia’s new “novel” strategic range delivery systems and large stockpile of non-strategic nuclear warheads. The success or failure new arms control talks will rise or fall in large part based on how these issues are addressed, not whether, for instance, the United States builds a new ICBM.—KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy, and SHANNON BUGOS, research associate

Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman informed Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov of the administration’s final decision on May 27, the Associated Press reported. A State Department spokesperson later confirmed the news and attributed the decision to “Russia’s failure to take any actions to return to compliance” with the treaty.

Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman informed Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov of the administration’s final decision on May 27, the Associated Press reported. A State Department spokesperson later confirmed the news and attributed the decision to “Russia’s failure to take any actions to return to compliance” with the treaty. Though the sunk costs to date have been relatively minimal, spending on nuclear weapons is slated to increase dramatically in the coming years. In contrast, the topline national defense budget will likely be flat at best. (The Biden administration’s FY 2022 defense topline

Though the sunk costs to date have been relatively minimal, spending on nuclear weapons is slated to increase dramatically in the coming years. In contrast, the topline national defense budget will likely be flat at best. (The Biden administration’s FY 2022 defense topline  The growing price tag of the nuclear mission is coinciding with Pentagon plans to recapitalize large portions of the nation’s conventional force. The last time the United States simultaneously modernized its conventional and nuclear forces in the 1980s, it did so alongside an increasing defense budget, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work recently

The growing price tag of the nuclear mission is coinciding with Pentagon plans to recapitalize large portions of the nation’s conventional force. The last time the United States simultaneously modernized its conventional and nuclear forces in the 1980s, it did so alongside an increasing defense budget, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work recently

Past independent assessments indicate that it is possible to extend the life of the existing Minuteman III missiles beyond their planned retirement in the 2030 timeframe, as the Defense Department has done before, by refurbishing the rocket motors and other parts.

Past independent assessments indicate that it is possible to extend the life of the existing Minuteman III missiles beyond their planned retirement in the 2030 timeframe, as the Defense Department has done before, by refurbishing the rocket motors and other parts. In remarks April 15, Biden said his proposed summit meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin could be a launching point for talks on strategic stability and nuclear arms control. Serious, sustained disarmament diplomacy is overdue and essential, but achieving new agreements will be challenging.

In remarks April 15, Biden said his proposed summit meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin could be a launching point for talks on strategic stability and nuclear arms control. Serious, sustained disarmament diplomacy is overdue and essential, but achieving new agreements will be challenging.